Resources Related to the Podcast

- Gary’s bio on Wikipedia

- American Business History Center

- How to Read a Book by Mortimer Adler

- AoM Article: How to Read More Books

- AoM Article: Culture You Can Heft

- AoM Article: 7 Reasons You Should Still Keep a Paper Map in Your Glovebox

- AoM Article: 100 Books Every Man Should Read

- AoM Article: The Best Way to Retain What You Read

- AoM Article: How and Why to Become a Lifelong Learner

- AoM Podcast #493: 1,000 Books to Read Before You Die

Connect With Gary Hoover

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Listen ad-free on Stitcher Premium; get a free month when you use code “manliness” at checkout.

Podcast Sponsors

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Read the Transcript!

If you appreciate the full text transcript, please consider donating to AoM. It will help cover the costs of transcription and allow other to enjoy it. Thank you!

Brett McKay: Brett McKay here and welcome to another edition of The Art of Manliness podcast. Now, Gary Hoover loves books. Among the nine companies he founded was the bookstore chain Bookstop, which was acquired by Barnes & Noble. He has a personal collection of, get this, 60,000 books, which he had to purchase an abandoned strip mall medical center to house and is the author of his own book which is about books, called The Lifetime Learner’s Guide to Reading and Learning. Today on the show, Gary shares how his fascination with books was born in his youth, why the collection he amassed over the decades is almost entirely non-fiction, why he prefers physical books over e-books, and why getting your hands on old books can be particularly beneficial in enhancing your knowledge of the world. From there, we turn to Gary’s method for digesting a book which allows him to glean its most valuable nuggets in just 30 minutes without having to read it cover to cover.

We also talk about whether Gary takes notes on the books he reads and how to incorporate more serendipity into the way you do your own reading and build your home library. After the show’s over check out our show notes at aom.is/hoover.

Alright. Gary Hoover, welcome to the show.

Gary Hoover: Hey, it’s great to be here, Brett. Thanks for having me.

Brett McKay: So you got a book called The Lifetime Learner’s Guide to Reading and Learning, and you’re an expert at this because you have been reading your entire life. In fact, you live in a house, you’ve got a 33-room building, 32 of them contain your personal library of 60,000 books. So we gotta start there, I thought my book collection was out of control. How did you end up with a collection of 60,000 books?

Gary Hoover: Boy, I think it really started when I was a little kid, and I remember I bought… They were books called the Golden Guides, the guides to the birds, and guides to the mammals and rocks and minerals and little paperback books. I’ve still got them. And I thought it was so great that I could look out and see something or observe anything in life and then go look it up and find out what it was and where it came from. And over time, I know at one point as a kid, I said, ‘Well, I’d like to compile a list of everything, everything that exist.” And I remember this sounds really weird, I went to a boat dealer and they had brochures about the different kind of boats they carried. And I was a little kid on a bicycle that lived in the neighborhood, and I started picking up all their brochures and they said, “Oh kid, you can’t have those.” They only had so many brochures or whatever, they were jealous of them, and I said, “Well, I just wanna learn about… ” Whatever the name of the boat companies were, and they said, “Well, get an encyclopedia.” And I said to myself, “What a stupid guy, the boat companies aren’t in encyclopedias.”

And I lived in this GM factory town, Anderson, Indiana, had like 27,000 General Motors workers in a town of 60,000 people, and yet when I went to look up General Motors, it wasn’t in the encyclopedia either. And so I’m like, “Well, there’s all this stuff and where do I find out about it?” And I got especially interested in companies ’cause I wanted to know about General Motors, how did it work? Not… If I asked my teachers, they said, “Oh, they make Chevrolet, Buick, Pontiac, Oldsmobile, Cadillac.” And I said, “No, no, no, I know that. But who started it and where did it come from? Who runs it today? Is it a good company or a bad company?” And I found out in the library there were great big books called Moody’s Manuals which told about every company in America, every company you could buy stock in, every public company, and I started going through those. I still have my notes. I would bicycle down to the library. I conned the librarian out of giving me his old set. A new set comes out every year and he gave me the old one. Great big heavy books. Now they sell for thousands of dollars, the new ones.

And I just… The idea, books to me, opened the whole world. I could study Brazil, I could study lizards, I could study General Motors. Everything was there somewhere in a book, and I started collecting them [chuckle] and my real, my first love… Well, one of them were… Trains and geography, I guess were my first loves, and so I started reading trains magazines, ’cause magazines have also always been very important to me and learning in a lot of ways beyond books, but I got into geography. My dad was a traveling salesman and then a sales manager, and he used to love to drive all over the country with the family, and I got to be the guy with the road atlas, the Rand McNally Road Atlas, which was one of the bestselling books in America for decades. And learned how to use maps, which are really works of art. And so actually atlas is I think the first book I bought with my own allowance. Well, one was on trains and the other was a world atlas for like 50 cents in the late ’50s when I was, I don’t know, seven or eight years old, and now I have pretty much every atlas you can buy.

I have frequent shopper cards from bookstores in Tel Aviv, Moscow, Chiang Mai, Singapore, where I’ve only been in once, but I walked in and I spent like $1000. I cleaned out all their atlas and map sections, and business sections and birds. And so, and I estimate, I think when you read my book, I think when I re-read it, I had two or three different numbers in there, but I would guess over 70% of what’s in my massive library is not available online, and that shocks people, especially younger people, when I tell them that. They think anything about geography or about travel or about birds or about companies, you can look up online. And yet a lot of the great stuff, the classics, they’re still under copyright, they haven’t been digitized, even if they’re off the copyright, there’s so much in books, it’s the only source. So to me, books are a form of magic. So I’ve never regretted buying a book. And I bought some that I really disliked or disagreed with, but still I help the publishing industry and I help the author, and so my life has just been… I’ve been a book seller, a book publisher, a book author, but above all else, a book collector.

Brett McKay: Okay, so basically, just from a young age, you’ve had this fascination with books started with the atlases, magazines. As you got into adulthood and your teenage, young adult years, was there a particular type of book you were looking for to add to your collection, or was it just any book that sparked your interest? Fiction, non-fiction, biography, you were gonna buy it.

Gary Hoover: No. I’m interested in understanding the way the world works. I always said that if I hadn’t become a retailer, which is really my profession most of my life and the field I love the most, I would have been a social scientist. Psychology, sociology, anthropology, economics, political science, understanding how society works, how you can make life better for people. And I was blessed to go to the University of Chicago, which has a real strong social sciences area. Four of my economics teachers later won Nobel Prizes. And to me, retailing is really just applied social sciences. So you’re applying geography, you’re applying economics, psychology, sociology, all that jazz, so. And really, trying to understand how the world works led me… A couple things. One is to study the classics, the basics. Like, if you’re gonna study business, you’ve really gotta start with Peter Drucker, the great business thinker. There’s all this stuff, all these new books published, but most of ’em are the fad of the month or of the year. They’re totally forgotten in six months or two or three years, whereas the basic lessons are timeless, so.

And I’m interested in facts. I’m interested in data. I prefer books that have charts and tables in them. I love big government reference books. And I can’t tell you how many books I have that all they are, are books full of numbers and data. And I prefer that to reading somebody’s opinion. I’ll read people’s opinion later. But I read so much of the current books, and it’s… They’re really trying to use emotion to tug on your purse, your strings, heart strings. I was starting to say purse strings. But…

Brett McKay: Sometimes purse strings.

Gary Hoover: Yeah. No, no, that’s true too. But sometimes… I remember one book, and the tables, the maps and stuff in the book said the opposite of what the author said of the whole premise of the book. And they couldn’t even read their own data right. So I wanna draw my own conclusions. I wanna be a skeptic. A skeptic, not a cynic, where a skeptic is from Missouri, show me, let me double-check the facts, I don’t really believe what you’re saying, till I double-check for myself. A cynic is somebody who distrusts your motives and thinks you’re up to evil and all that. So I’m never cynical, but I’m always skeptical. So my library is non-fiction. My library is full of books, full of facts and data, encyclopedias and dictionaries on every subject you can imagine. It’s really, I always say I pretty much cover every subject, except cooking and sports. I don’t cook, but I do have a lot of books about food. The history of foods and vegetables and fruits. And I have… Coming from Indiana, I love auto racing and I love basketball. So I have sections on them. I kinda got into World Cup, but my baseball friends would say, “Oh, you have a terrible library.”

At the same time, with 60,000 books, somebody will say to me, “Well, do you have much on this subject?” I say, “No, no, not much. Only 12 books.” So sometimes what to me is insignificant or was just a brief interest for a few weeks, although I usually keep every interest I… I gain new interest every year and then I keep everything. But what to some people would be a big library, to me, I tend to, when I’m interested in a subject, like the nine books that came today, well, four of them were on the same subject. Well, I said, “Well, I really wanna get my head around that, and I wanna compare what different authors are saying. But I especially want books with data, facts and information.” So my attention span is just too short for a big fat novel. I’ve always said, “Hey, if I ever really got into literature, it would cost me a fortune ’cause I’d have to buy another 40,000 books or whatever, 60,000 books.”

Gary Hoover: But I do enjoy short stories and I enjoy movies. But real life, non-fiction, nothing could be more amazing. You read the biographies of these great people, these great business people that I study and write up on my websites and stuff, and no fictional story is more dramatic or heart-wrenching or whatever. So, no, my library is really… And selective. When I had the book store chain that I started, my friends and I did, I got free books from the publishers and I would turn them away, or I would put them out on the front desk to say, “Anybody who wants these, take these,” because they would give me books that I didn’t really want in my library.

On the other hand, I have other places in my library where there’s a gap on the shelf. I keep a list of important books that haven’t been written yet, where I say, “Nobody has written X.” For example, there hasn’t been a good history of the General Electric company written since like the 1940s. And that’s crazy, as important as that company is and all the changes they’ve been through. And so I’ve got a gap waiting for somebody to write that book. In a sense, mine is a very selective approach, even though it’s come to 60,000 books now.

Brett McKay: I’d like to talk about how you select books, and also how you organize your books. You said you have spots available. Before we do, I think the question some people might be thinking right now is like, “Why physical books? Why do you still need two rooms when you could just get a lot of these on a Kindle?”

Gary Hoover: Yes, yes. Books, the portability, the ability to read ’em on a beach or on an airplane or in bed and everything. I use a tablet, I love my tablet, but it just doesn’t hold the same way. But for me, the… And the durability of these books now, they’re made on acid-free paper, so they’re gonna be around for hundreds and hundreds of years. I’ve already got some books that are 200-plus years old. But the main thing is that the way I, what I call, digest a book, that was the best word I could come up with, I don’t read a book sequentially. I don’t open it up and start at the front and read it to the back end. I have my own system, because I really believe in efficient learning. I wanna learn as much as I can and understand as much as I can as efficiently, the best use of my time. And so my method is set to do that, and I, when I get a new book, I’ll spend 15-30 minutes with it to really understand it and get the key ideas. And I can go into details on that, and that’s all covered in my book, The Lifetime Learner’s Guide.

But Kindle and all that, they’re wonderful, and I totally understand the appeal. They’re light weight and have 1000 books on the gadget and all that. But you can’t really do my non-sequential reading method, and you can’t do it fast with an e-book. Some of my books will have 30-40 bookmarks in ’em, places I’ve noted, the important pages. Most of them have three or four or five. I use little origami paper, little like 2X2 inch squares, so it doesn’t bend the book, and it’s easy to find. And I, in my method, I make heavy use of the index. So I’m looking up things that I already know something about, because that’s what allows me to remember pretty much everything I read or all the important ideas, because I… Like, okay, so I know a lot about the history of General Motors, having grown up in a General Motors town. I know less about Ford. They were the evil enemy when I was a kid.

And so when I buy a book, or a biography of Henry Ford or a book about the Ford Motor Company, which is an amazing company, I go to the index and I look up General Motors. I look up Alfred Sloan. He was the man who really ran General Motors and built it into the great company that it was, before it went into decline in the last 30 years. And then I read and I find oh, they knew each other or they hated each other or they liked each other or they never met or they competed. When Ford brought out the V8 in the ’30s or whatever, and how did GM react. So I’m always using that index. And I can be in a position where I’ll have literally have like six or seven of my fingers in pages, in between them, and I’ll be flying back and forth between, wait, this table says this and this paragraph says that, or this section says this and this says that. And you just can’t do that with an e-book. And I can move very quickly.

A kind of a parallel thing is the use of paper maps. I did a blog post once about why we need paper maps. When I’m doing a Google map or a map on my tablet or on a smartphone or anything, it can tell you how to get from here to there, but it can’t tell you what detours you might make, it can’t tell you about that jazz festival you’ve always wanted to see that’s only 10 miles off the road, or that cool museum or… And the thing is, if you take a old-fashion big paper map or a road atlas, you can zoom in and out at incredibly high speed. If I take a big folding old gas station map of Texas, I can zoom in and look at everything right around the little town of Flatonia where I live, and then I can just, by moving that map and moving my eyes, I can get the whole scope, I can understand how it fits into its context, because I’m always looking for context. Whatever subject I’m looking at, what is around it? What happened before it, what happened after it? What competed with it?

And so the kinda things I do, you just, you can’t do with an e-book. It would take much more time and much harder to fly back and forth, because I’m not reading from the front to the back. I just don’t have the time or patience for that. I wanna understand the book, get my head around it. And I spend a huge amount of time on the table of contents. I’ll stop 10, 15, of that 15 minutes, half of that time might be on the table of contents. If it’s well-constructed, it’s basically an outline of the book. And I can look at those chapter headings and say, no, wait a minute. Why on earth is that in this book? I don’t understand that. And I’ll go read the first and the last paragraph of that chapter, whatever, understand, well, why is it here or I’ll say, ah, that chapter’s exactly… I was trying to figure out why the oil industry moved from Pennsylvania to Texas. What was Spindletop? Ah, there is a chapter about the history of Spindletop, which was the first big strike in Texas, and got all the big oil guys to start looking down here instead of just in Pennsylvania and Ohio. And yeah, so those are some of the things I do.

Brett McKay: Yeah. And another… That’s the reason I like physical books too. It’s a lot easier to manipulate, and you can go back and forth really quickly. On the Kindle, it’s designed to read sequentially, which is really frustrating. The other benefit to physical books and keeping a library of physical books, I’ve noticed with my… I’ve got hundreds and hundreds of books on my Kindle, but once I read a book on Kindle, I forget about it. When I have a physical book, for some reasons, I pass by it and it allow… Having that library allows me to like, well, I want… I’m looking for this topic, I know I have a book, and I… Something about the physicality of it, I can locate things. Or it allows for serendipitous, like, well, I wanna… Oh, I’m looking for this book, but I… Ah, here’s this book that’s sort of connected to that idea. Maybe I’ll dig into that. I can open that, flip through the book really fast. You can’t do that with a Kindle.

Gary Hoover: No, absolutely. And also, there have been some studies that indicate you learn differently when you read electronically. And the other thing too is, I do spend a huge share of my life in front of a screen. I’m in front of a screen right now. And I write and I do read. I read a lot of PDFs. I’m probably on Wikipedia 30, 40 times a day, I’m Googling all over. So at some point, your eyes get tired, as you get old like me and so I think there’s a limit to how much time you should spend. And especially when I say especially young people doing it in dark rooms and stuff, and the contrast between the bright screen and the darkness around you. I don’t think to do that long-term. I guess these movie critics that sit there and watch 15 movies in a row, they’ve figured out how to adapt to it. But no, no, books are just… And I don’t know if you’ve looked at the numbers, but print books are growing faster than e-books and have been for several years. Bookstores, which had really been through the ringer with Amazon and everything, they’ve bounced back, the best independent book stores in the country now are doing pretty well, the ones that are allowed to open. People…

People understand and get the idea of books. And I see more and more websites about books, the best books to read, fiction and non-fiction. So I think the trends are going in the right direction, and books are gonna be around forever, ’cause I think about, “Oh, what are all these books gonna be worth, when I die? And are they gonna be worthless and they just take ’em and put ’em in a dumpster, or are they gonna be worth a fortune?” I hope the latter, ’cause the money will go to my favorite charities.

Brett McKay: And so how do you organize your books? Do you Dewey decimal system or do you have your unique Gary Hoover?

Gary Hoover: In my head, in my head. Each of my rooms here, I found just a bargain on a community health clinic with 30 some little exam rooms that had gone broke and was sitting here vacant for a couple of years in this little historic railroad town of Flatonia, Texas. And I said, “Wow, that’s the place for me to move to.” So each room is a different subject. There are a couple of subjects that take up two rooms and the rooms are of different sizes. Took me about three months to plan out all 200 bookcases, all 60000 books. What went where? How many do I have, of each subject? And fit them in small rooms and big rooms. I’ve been told I’m on an Advisory Council of the Graduate School of Information at the University of Texas at Austin, and that used to be the library school. We still train librarians, but the school also does user experience and how to use the web and all that. But they told me that when a big library gets a gift of some big private library, one like mine, that they often find that the owner has had their own system, and they usually learn from that. They see a different way of connecting things, and I learned…

Having developed with my friends, a bookstore chain, I learned, “Man, there are a lot of books.” I never realized, but a lot of books can go into two subjects. You have books that are about Philosophy and Physics. So does it go in Philosophy or does it go in Physics? Book stores have a Biography section. But if you have a biography of George Gershwin or Igor Stravinsky, does that go in the Music section or does that go in the Biography section? And it’s very difficult to put a book in two different sections and keep track of that. That really challenges the technology, to make that all work. And if you sell out in one area and forget to refill it. So you pretty much have to put them in one place or the other. So no, I essentially have my own system, but I think, when I move on to the big library in the sky, my house will become a used book store. And I think most good book collectors will find it great, because, “Oh, that’s the railroad room. Oh, those are the two architecture rooms. Oh, that’s the nature room. That’s the bird book cabinet or bookcase. The tree book section.” So for most people, I think it’ll work and be pretty straightforward.

Brett McKay: We’re gonna take a quick break, for a word from our sponsors. And now, back to the show. So let’s walk through your process on how you digest a non-fiction book. You said that you can do it in 15 to 30 minutes and you’re not reading the entire book, you’re…

Gary Hoover: No.

Brett McKay: You’re doing sort of a… You’re manipulating the book, so you figure out… This is how you screen books, whether you should hold on to it and dig deeper into it, correct?

Gary Hoover: Yeah, yeah. And most of the books that I buy, I have checked them out enough on Amazon or read reviews online or whatever. So I already know I’m interested in the book and wanna learn from it. I think the first step is, and I’ve talked to a lot of the people about these subjects, and I think some people have trouble with this, but the first thing is to realize, the book is mine. The minute I paid for it, or borrowed it from a library, I believe in libraries and been very supportive of libraries, the minute I get it, it’s mine, and I can read it if I want, I can not read it, I can read it backwards if I want. [chuckle] I can just stare at one map in the middle of it for an hour and ignore the rest. It’s my book, and I can do what I want with it. And it’s gotta interact with my mind in the way my mind works. So first of all, I wanna look at what’s the basic thesis of this book? Who is the author and where are they coming from? What are their credentials?

Now, I’m not obsessed just with, “Okay, they’ve got a PhD from Harvard, they’ve got four PhDs from Harvard and Yale and whatever, and therefore they’re smart.” No, but that is worth knowing, and say, “Well, at least they spent a lot of time going to school and those are supposed to be pretty good schools.” But I studied philosophy, there are a lot of old Greeks that didn’t go to Harvard. And there’s a guy named Eric Hoffer, H-O-F-F-E-R, who was as good as any of them and he was like a pea-picker and a longshoreman, who didn’t have any degrees of any type. But I still wanna know. And if I’m reading, I love what I would call political economy, where politics and economics interrelate, and people come from the left, people come from the right. Well, I wanna know that. And before I start… And so I do, I read the biography of the author. This sounds strange, but I even look at the publisher, because I’ve been in the book business long enough and collected enough books to know that if it’s a railroad book from Indiana University Press or if it’s a book about Western History from the University of Oklahoma Press, or if it’s pretty much any book from the Oxford University Press, one of their handbooks, a column on all kinds of different subjects, I know, “Hey, that’s gonna be a pretty darn good book.”

Those Editors know what they’re doing and know that subject. So I will even glance at the publisher. But I’ll really study that table of contents, that outline of the book. If it’s done right, it’ll really tell me what the chapters are saying, what order they’re in, what ones I’m most interested in, and then I delve into that index. I look for things I’ve already heard of. If I’m… I studied under Milton Friedman at the University Of Chicago, in Economics. If I’m reading a book on the history of the car industry, and there’s an entry in the index for Friedman, and I’m like, “What’s that doing it here? Why could he relate to the car industry?” Both subjects I love. Economics and the history of the auto industry, and I look and say, “Well, why isn’t that in the index?” I won’t buy a book if there’s something important that’s not in the index, that I think should be there. A history of the auto industry that doesn’t mention Henry Ford. Well, that’s nuts. I don’t think a book like that exists, but I’ve seen some pretty bad examples. And then I read the sections.

Depending on the type of book, I’ll read the first paragraph of the book, the last paragraph, I might read the whole first chapter. And the other thing, if you look at current business books, and again, that’s an area where I say, “Well, I don’t really collect those,” and yet I probably have a thousand that were current business books at the time, over the last 50 years, a lot of them, they should have been a magazine article, they should have been 30 pages or whatever. And they say, “Here’s my big idea, and here’s an example of it, and here’s another example, and here’s another example,” and I’m like, “Well, if I don’t get your basic idea by example number two, maybe I should stop and slow down and think about it and read that example again, and maybe even do more research, look it up online or Wikipedia or whatever.” I don’t need you telling me the same thing over and over, to fill up a 250-page book so it makes a fat book that you can charge money for.

And an awful lot of it is about slowing down. I’m not a speed reader, they gave me remedial reading in seventh grade or whatever, I didn’t do very well. I have to stop each sentence or each paragraph. If it really has something to say, if it isn’t just fluff, I need to stop and think about it. I remember, as a kid, it always took me forever to do homework, especially in the social sciences which I love, because I’d read something about history or geography, or about Brazil or Indonesia, and I would go off daydreaming about it for 30 minutes, and then, “Oh, now I gotta answer this stupid question in the homework.” And I took longer than anybody else that I know of. Sitting there doing homework because I would be off thinking about, “Well, what’s that really mean? And is that really true? Can I look it up somewhere else?” So I’m really engaged with what I read, but I don’t wanna be reading the fluff. So I have once in a while, read a book cover to cover, but I find it kind of painful.

Brett McKay: Right. Okay, so in 15 minutes, you’re looking at the biography of the author, their credentials, their history, why they’re writing this book, you’re gonna look at the table of contents, which is really useful. I don’t think a lot of people do that, make sure to see the general outline, then you might read the first chapter, maybe a little bit of the last part of the book, to see the conclusion, then you also mentioned the index, you’re gonna make use of that index to see, “Are they hitting on stuff that I think should be in this book? If it’s not in there, this is probably not a good book,” etcetera.

Gary Hoover: Yep, yep. No, the index is huge, and I also… If a book has footnotes and a bibliography, if it’s a subject I know something about, I’ll look at that bibliography and say, “Okay, have they looked at the books I know are good in this field?” And sometimes I’ll find a book and say, “Wait a minute, they didn’t even read that book and they’re writing this book about the same subject? Man, this is not a good sign.” Other times, I’ll say, “Wow, they have, they’ve read all these other books I already have.” And then I gotta tell you, over half of all the books I buy, are triggered by a bibliography or a footnote, where I’ve got a book and I’d said, “Wow, this looks like a great book, where they got this information or this data. I need to order that.”

So an enormous share of the books I buy are at least 30 years old. A lot of the best stuff that I have is… That I learned from, is from the ’20s and ’30s, but certainly the ’70s and the ’80s, and what’s interesting is, those older books, certainly anything over 20 or 30 years old, can be very difficult to find on Amazon. They’re on there, but their search system is so focused on the more recent books, that I find it’s… 90% of the time, it’s faster to type in the author’s name and the title in Google search, it’ll show me an Amazon link, hit that, and the book will show right up. Whereas if I try to use the search box on Amazon, some of them are buried 30 pages deep, even when you type in the name of the book and the author. Their Amazon search has really gone downhill over the years, so somebody’s not paying attention there. And yet of course, I use Amazon every day and I wouldn’t be able to have my library without them.

Brett McKay: Oh, so this sounds like this 15… This literally takes 15 to 30 minutes. This sounds like sort of the inspectional reading of Mortimer Adler, of How to Read a Book, fame.

Gary Hoover: Absolutely, How to Read a Book, that’s a great book.

Brett McKay: And you mentioned another benefit of paperback or just physical books is that, the older books, I’ve noticed this too, is I get more out of an older book that was written 40, 50, 60, 70 years ago, compared to a book that was written just recently. And it’s amazing, none of that stuff… A lot of these books, the information in there isn’t online, so if you didn’t read the book, you never would have known about this stuff.

Gary Hoover: No, absolutely. And the other thing too is, especially when I’m studying organizations, business, governments, economies, when you have an old book, you can see the full arc of whatever the idea or the organization was, or a technology. I’ve been studying the history of the telegraph, which was really the beginnings of telecommunications. Well, with the old things, you can see how they rose up, how they prospered, how they peaked, how they maybe made a bunch of people rich, or a lot of people tried to get rich, like the gold strikes in California in the 1840s and stuff, the gold rush, and then you see, well, how they died. And so, if I read a book about… Oh gosh, I can find books in my library, that are how the Japanese are gonna take over the world, and it probably would have been what, the ’70s or ’80s. Japanese companies were buying American movie studios, they were buying other American companies, the Japanese were just beating us to death, and oh, all the US companies are gonna be owned by the Japanese. Well, that’s a really interesting book to read, ’cause then I can look and then go, “Well, what was their logic and what did they think and why did that not turn out to be true?”

And then a few years later, I can find you another book, or two or three or four, that’s the Saudis that are gonna own the whole world. And they have all the money in the world and they’re gonna buy up everything in America. The Gulf States countries and everything, Dubai and Abu Dhabi and all that, and that hasn’t quite come true. I can read books about, “There’s a great company, look at it, they’re all gonna set records and everything.” A book from the 50s and then that company’s bankrupt by 1975. And sometimes I have to go outside the book, go to Wikipedia or… Wikipedia is really spotty on business history. Sometimes awful, sometimes good. But there are other places I dig. If the company still exists, I can pull their annual report or I can look at their stock chart on Yahoo Finance or something like that. So those old books, you can learn so much, if you’re willing to take the time to stop and think on your own and really think about what you’re reading, why they wrote it, why they felt that way, where they went wrong and where they were right.

Brett McKay: So you’re using this inspectional reading process and trying to extract the information that you think is the most useful, by using this process. How do you take notes on a book? Do you have a notebook that you use to take notes and keep track? What is it?

Gary Hoover: Yeah, no. I’m afraid my answer there, may not be very satisfying. I don’t take notes. I take notes in my head, but at the same time, I do, I put bookmarks in these books, these origami paper, little 2 inch x 2 inch sheets. And any time I see an important table or chart or a quote or, “Oh, this was an event in this person’s life,” anything I think, “Man, that’s something I wanna… When I come back this book, that’s one of the pages I wanna look at.” And so I’ve got books that have 30 or 40 or more of those little origami bookmarks in them. Usually just four or five or six or seven, but… And those stay in the books. They go back on the shelf with those bookmarks in them. So that’s probably the closest I come. And then a lot of the ideas, ’cause I really believe in what I called in my book, “Getting In the Flow,” that information, the more you use it… So if I learn something, I feel I have a… I don’t know if it’s an obligation or a duty, but I feel I need to share that. I can’t keep my mouth shut about it. And that, in my case, takes the form of writing. I make speeches and I teach classes too, but most of it, I write and I have two websites and have all this stuff I’ve written over the last several years, and books.

Like Peter Drucker said, “The best way to learn a subject is to teach it.” So if I can take what I learn and either write it up or talk about it to somebody, anybody, that just pounds it deeper into my memory. And so, I think most important stuff and drawing conclusions. But I do, I write to myself a lot. I can’t tell you how many Word documents I have, that nobody but me has ever seen, where I’ll just go off on a riff, say, “Oh, what about that subject?” and I’ll just write up my thoughts and put them away. And so that is a form of note-taking, and sometimes I won’t look at it for four or five years, and I’ll look back at it and say, “Oh man, I was full of it. I had it all wrong,” or “Wow, you know, I’m smarter than I thought I was.”

Brett McKay: Alright, yeah. So it sounds like… And that’s been my experience too. I don’t have a note-taking system either. I just… I read and then I typically have to write something about it, I have to synthesize it, and produce it on the blog or for the podcast. That’s how I remember stuff.

Gary Hoover: Yeah. Synthesizing. In your head or in notes. Yeah, always synthesizing.

Brett McKay: And another thing you do, that I’ve done intuitively, but you make it explicit, is you… As you’re reading and you’re taking in new information, you think about what you’re reading this or the information, the new information in terms of concepts, clusters, patterns and chains. And this also helps you kinda organize in your head. Briefly… You can’t go too deep, but briefly, what does that look like, thinking in concepts, clusters, patterns and chains?

Gary Hoover: Yeah, well, a few basic things. I go into depth on all that in the book, and there’s a lot in there. But one thing is, I’m always trying to get on a higher hill than other people. I’m always trying to walk a little further up the mountain, to get a little better view of the landscape, of the context of the countryside. When I look at something, I always ask, “What is this a component of and what are its components?” That’s part of something you might call systems thinking or General Systems Theory. I recommend the great book about general systems thinking, but it’s an understanding that sub nuclear particles are part of a nucleus, are part of an atom, are part of a molecule, are part of a cell, are part of an organism or a being, are part of a community, are part of a city, are part of a state, are part of a country, are part of a nation, are a part of a world, are part of the globe, the world, a part of the solar system, are part of the galaxy. You with me? It’s a chain that extends. And that’s true of everything. So I’m always looking, “Well, what’s this a part of? What’s the… “

If I’m studying the Island of Java, which I visited a couple of times. A wonderful place that has more people on it than any island in the world. Well, I can’t understand it unless I understand it’s part of Indonesia. I can’t understand stuff unless I understand the context, what’s around. And there’s no way I can understand General Motors and how it’s done if I don’t understand Toyota. When I was a young planner, an analyst to the big department store company, we were looking at companies to buy, to acquire, and they said, “Well go look at the shoe store chain.” And I did, but I brought them a report that none of my bosses asked for. I was just a kid in late, mid, late 20s. I brought back a whole report on the shoe store industry and who are all their competitors and how they fit in. Because I didn’t want my bosses having this abridged understanding of what they might be getting into. And they ended up buying a shoe store chain, and it was the most successful acquisition in the history of the company I worked for, but… So I’m always trying to step back, see further, knit together more.

If you study Peter Drucker, the great business writer and thinker, he is one of the very few people who understood demographics…

Sociology, psychology, business, economics, geography, and everything he wrote, he had that all in his head. I call it wisdom, that understanding of how the pieces fit together. So those are some general thoughts on that.

Brett McKay: Yeah, big picture. When you’re reading, make sure you see how it fits into a bigger picture.

Gary Hoover: Yeah.

Brett McKay: So it gives you context and…

Gary Hoover: Absolutely.

Brett McKay: Gives you more information. So another thing you talk about in the book, in depth, was the importance of adding some serendipity in your reading, in your learning. Why is that important, to incorporate serendipity and how do you do that with your own learning?

Gary Hoover: Yeah. At this stage of the game, I think my mind has just gone serendipitous, because I’ll sit here… I’m well known. I’ll be driving down the freeway and I’ll see a billboard for a company I’ve never heard of, and I’ll have to pull off onto the shoulder of the interstate and pull out my tablet, if I’ve got a connection, and look up the company. I talk in the book, about… Book learning is critically important, so key to my life, but also observation, conversation, experimentation, travel, all these other ways that we learn. It just doesn’t take much, to distract me. I remember, this was some years ago, that I watch TV ads and I say, “What can I learn from them?” And you see new products introduced and all that, but one time I saw an ad, and it was for these Ram trucks. Well, Ram was a brand of Dodge, and it was called the Dodge Ram, when they came out with a Ram truck.

But I noticed that TV ad, they never once used the word “Dodge” and I said, “Wow, that’s… Within the history of the auto industry, that’s big news.” Because, what does that mean? That means that the Chrysler Corporation is gonna break Ram out as its own brand, and that means that they’re gonna have separate dealerships at some point, and that means maybe they have too many Dodge dealers or they have Dodge dealers that wanna give up on the cars and just do trucks, or they have new dealers saying, “Look, we wanna sell your products, we just want those Ram trucks.” And it’s a safe bet, that very, very, very few other people who’d saw that responded to it the way I did and thought about it in that context. And I still meet people that think they’re Dodge Rams. Well, no, not really anymore. And Ram has been hugely successful, Dodge somewhat less so and now it’s under a whole new management and they have overall done a great job with it, they also own the Jeep brand. But I’m always…

But the example I always use on serendipity is, when I learn words and vocabulary, I look them up in a physical dictionary. And on the way to look up any word, I would stumble across five or 10 or 20 other words, or words right next to it on the same page that, “Oh, I never heard that word before. What’s that mean?” Well, now, if I go online and I look up the definition of the word, all I do is get the definition of that word, and it’s just like the map issue, where, “Hey, this is only gonna tell me how to get to Dallas the fastest way. It isn’t gonna tell me anything about what’s interesting just off the road, or where there’s a good diner, a good barbecue place a few miles away, or a state parklet school, or a music event, or concert, or whatever.

And so, a lot of it is about being chill, about relaxing. The answers to most of your questions are not gonna be found where you’re looking for them. I have all these friends that read book… Whatever they wanna learn. I wanna learn to program in Java or whatever, and they read book after book after book, and I’m not saying there’s anything wrong with that. When I wanna learn a subject, I get the most basic, classic book. If there’s a subject I know nothing about, particularly, in the sciences or math, I’ll get one of those ‘for Dummies’ books and I’ll start it… ’cause I want to build a foundation of understanding before I try to go deeper or understand. But just grazing and having your eyes open, I think, and being… ’cause you meet people who say, “Oh, I won’t go to that concert, I don’t like that kind of music. Oh, I don’t like those kind of movies. I won’t go to that movie. I don’t wanna visit that country, I don’t like the people.” But hey, you’re just cutting yourself off. It’s sad.

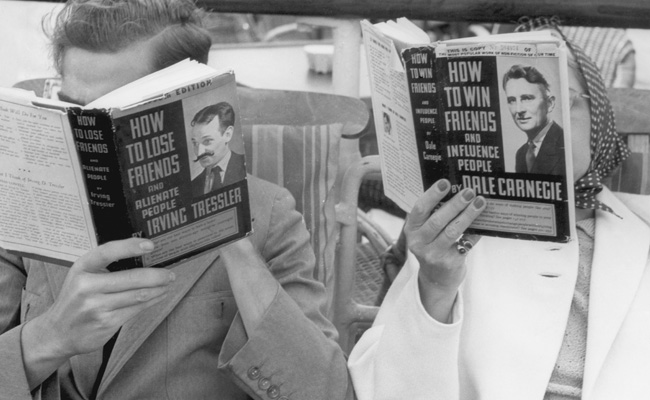

Brett McKay: No, in my experience, the way I inject serendipity with my reading is, I like… So I buy most of my books from online, on Amazon. And Amazon has that feature, readers who bought this book also bought that, and I’ve used that, but you end up just seeing the same things over and over again. But the way, if you wanna get out of that loop or that bubble is, you’d go to a physical bookstore or the library. The best place to go, that I found, if you just wanna find just pleasant surprises is a used bookstore though, ’cause that just has stuff from 50, 60, 40 years ago, that you would never come across in a Barnes & Noble, it would never come up in Amazon, and you stumble upon in some weird section of the used bookstore like, “Wow! I never would have found this if I hadn’t been just sorta wondering around this used bookstore.”

Gary Hoover: Oh, absolutely, absolutely. To both of what you say. And the use of bookstores, where there’s Barnes & Noble or many great independent stores, when I go into a Barnes & Noble… I live out in the country now, so I’m 45 minutes or an hour away from one, but when I travel, I always stop in, I go to dozens of them every year. And when I go in and I come out, I buy as many books as my budget or credit card will allow, at Barnes & Noble ’cause I wanna support retail stores, and the bookstore chain I started, sold out to Barnes & Noble, so I have friends there. But I also come out with a list of about 30 other books that I write down. I carry little tablets in my pocket, that’s my ultimate note-keeping system. And I come out with a list of 30 books that I wanna buy later when I have the money, that I never would have discovered without that. And then you’re right, used bookstores take that to a whole another level, especially a really great one.

Two of my favorites would be Powell’s Bookstore, City of Books in Portland, Oregon, probably the best single bookstore in America, the Strand, in New York City, and then in Dallas, Half Price Books is a giant chain of used bookstores, it’s a great company all over America, but they’re big. I call it the mothership. Their main store where their headquarters is, in the north side of Dallas, is just a wonderland of books. So yeah, no, you can’t beat a physical bookstore, for stumbling across things you didn’t think you would be interested in, things you didn’t know anybody ever wrote a book about, things you were interested in, but didn’t know there was this book about them, because a lot of that stuff gets buried on Amazon and it’s hard to find, even if you’re searching for a subject you like.

Brett McKay: And again, you can do this process we talked about. That inspectional reading as you’re just, “Wow. Very quickly then I’m gonna buy this book so that I can delve deeper into it.”

Gary Hoover: Absolutely, man. In a bookstore, I open that book, I go straight to the table of contents and the index, stand there as long as I need to, and either put it in my basket or put it back on the shelf.

Brett McKay: Well Gary, this has been a great conversation. Where can people go to learn more about the book and the rest of your work?

Gary Hoover: Yeah. Well, the easy way on the book is, it’s on Amazon, “The Lifetime Learner’s Guide to Reading and Learning.” And the other thing is, I wrote a book many years ago, about how to start businesses and includes some of the same ideas about how to dream up ideas and how to think, but has a lot more about business. It’s called “The Art of Enterprise,” but it’s only available as a PDF. I did… The book itself is out of print, so I did a PDF version. I added some chapters. And if you go to my website, it’s called hooversworld.com, and you’ll see a link there, for the classes I teach and the books I have for sale, but that also has everything I’ve written. But most of my energy these days, I’m always… In anything I study, and certainly when I started companies, if you count all the ones I did in college, I think I started nine companies too, which were very successful, had some big failures too, but I’m always looking for gaps and vacancies and where is something the world isn’t looking at, that they should be. And that led my friends and I, to create a website called americanbusinesshistory.org, and that we tell a story of a great business, an industry, a company or a great business leader.

And we also have data, demographics, where are Americans moving to and moving from, because that relates to the history of the economy and business. And we do a week… Free weekly newsletter, and that’s where I put the vast majority of my energy today. Because when I Googled business history or American business history, there was nothing. There’s not a species, a breed of dogs or a species of bird, or a rare type of mineral that you can’t find 10-15 websites about. But there was no website, a central place where you can go, to learn about the history of American business. And as part of that context, always, I’m always asking, “What’s the history? Who invented this idea? How did this develop? Who invented this technology? Who started this company?” Whatever the subject. Who founded this nation? I wanna know the history first. Where did it come from? And in the business world, other fields, law, economics, law, medicine, they study history. All they do in law is study history, precedents and everything. But I can tell you, I meet more people with MBAs that they don’t even require you to study business history at even our greatest business schools, and so people are lost. They aren’t learning the lessons of the past, both the successes and the failures.

There’s no better way to learn entrepreneurship and business, than to study of the biographies of the great. How they thought, how they acted, how they overcame obstacles, that they were human, they weren’t a bunch of geniuses. And so that was a huge gap, I believe, in American business and business education and one that… To be blunt, I was the ideal person to fulfill because I’ve been fascinated by it since 1963, the history of all of these. And we cover every industry, every type of business, big, small, family-owned, giants, mergers, Amazon, Sears Roebuck, you name it. And so americanbusinesshistory.org is my main passion these days. But between American business and the Hoover Squirrel that I publish occasional newsletters that’ll deal with things that are less historical, but I do a weekly one for americanbusinesshistory.org.

Brett McKay: And just another quick plug for ‘The Lifetime Learner’s Guide to Reading and Learning.” You’ve got a reading list there, of 160 books, and I found that really useful ’cause you kind of organize it in big topics like thinking, psychology, world history, cities, and I’ve added a whole bunch of books to my Amazon wishlist, thanks to that.

Gary Hoover: Well, great. And most of those books are one’s nobody’s ever heard of.

Brett McKay: Yeah, no, a lot of them, I’ve never heard of. So what I like about it, it’s all that high-level stuff so that you can… I don’t know, I think it’s useful for anyone, to check that out. Gary, this has been a great conversation. Thanks for your time, it’s been a pleasure.

Gary Hoover: Hey, Brett, I’ve really enjoyed it. And if anybody goes to either of my websites and clicks on ‘Contact’, go to hooversworld, they can always email me directly. I answer all my own emails as fast as I can, and I love meeting people, talking and thinking about ideas. I do a lot of emails, my friends can tell you way too many. I’m a night owl, so you can email me at three in the morning and I’ll probably answer you pretty quickly. And so, yeah, well it’s been a pleasure, and I hope all the listeners are always learning. Every night, ask yourself, “What did I learn today?” And then later, you can ask yourself, “How can I apply it?” but the first thing is the learning.

Brett McKay: My guest today, was Gary Hoover. He’s the author of the book, “The Lifetime Learner’s Guide to Reading and Learning.” It’s available on amazon.com. You can find out more information about his work at his website, hooversworld.com. Also check out our show notes at aom.is/hoover, where you can find links to resources, where you can delve deeper into this topic.

Brett McKay: Well, that wraps up another edition of the AOM podcast. Check out our website at artofmaniless.com where you’ll find our podcast archives as well as thousands of articles written over the years, about pretty much anything you can think of. And if you’d like to enjoy ad-free episodes of the AOM podcast, you can do so on Stitcher Premium. Head over to stitcherpremium.com, sign up, use code ‘MANLINESS’ at check out, for a free month trial. Once you’re signed up, download the Stitcher app on Android and IOS and you can start enjoying ad-free episodes of the AOM podcast. And if you haven’t done so already, I’d appreciate if you take one minute to give us a review on Apple podcast or Stitcher. It helps out a lot. And if you’ve done that already, thank you. Please consider sharing the show with a friend or a family member who you think will get something out of it. As always, thank you for the continued support. Until next time, this is Brett McKay, reminding you to not only to listen to the AOM podcast, but put what you’ve heard, into action.