Who was the greatest Deputy U.S. Marshal of the Old West?

Wyatt Earp?

Wild Bill Hickok?

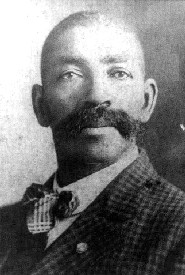

How about Bass Reeves? Bass who?

Deputy U.S. Marshal Bass Reeves was arguably the greatest lawman and gunfighter of the West, a man who served as a marshal for 32 years in the most dangerous district in the country, captured 3,000 felons, (once bringing in 17 men at one time), and shot 14 men in the line of duty, all without ever being shot himself.

He was also a black dude.

To understand the story of Bass Reeves, you first need to understand a bit of the fascinating history of Oklahoma. Let’s start there.

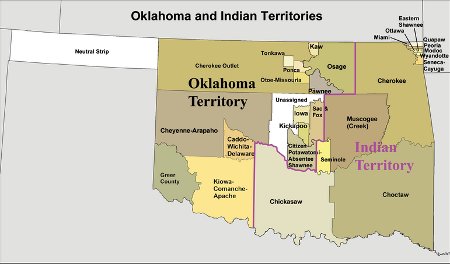

Before Oklahoma was a state, it was a territory. When the “Five Civilized Tribes” (Creeks, Cherokees, Choctaws, Seminoles, and Chickasaws) were forcibly removed from their ancestral homes in the Southeast, they were relocated to the middle of the country, to an area called the Indian Territory.

Because the Five Tribes sided with the Confederacy during the Civil War, the federal government forced them to renegotiate their treaties and cede the Western half of Indian Territory for the settlement of other tribes. This was called the Oklahoma Territory, and it was opened in 1890 to white settlers. The two territories were referred to as the “Twin Territories.”

The Indian Territory boasted an unusual mix of peoples and cultures. It was the home of Indians, Indian Freedmen (the black slaves of the Indians who were emancipated after the Civil War and made citizens of the Five Tribes), white settlers and African-Americans who had formerly been slaves to white masters in the South who rented land from the Indians as sharecroppers, and finally, outlaws fleeing the law and squatting on the land.

The Indian Lightforce police and the tribal courts governed this diverse population. But the tribal courts only had jurisdiction over citizens of the Five Tribes. So if a crime was a committed by an Indian and/or it involved a fellow Indian, it was handled by these tribal courts.

Non-Freedmen blacks, whites, and Indians who committed a crime against a person who was not a citizen of the Indian nations had to be tried in the U.S. federal courts in Paris, Texas and Fort Smith, Arkansas. And so the only U.S. law enforcement officers or judicial figures in Indian Territory were the U.S. Marshals, who rode for miles over the prairies, for months at a time, looking for wanted criminals to arrest and bring back to Fort Smith or Paris.

This made the Indian Territory a highly desirable place for horse thieves, bootleggers, murderers and outlaws of all varieties to hide out and lay low. At the time, it was estimated that of the 22,000 whites living in Indian Territory, 17,000 of them were criminals. This was truly the Wild West, or as the saying of the time went, “No Sunday West of St. Louis. No God West of Fort Smith.”

“Eighty miles west of Fort Smith was known as “the dead line,” and whenever a deputy marshal from Fort Smith or Paris, Texas, crossed the Missouri, Kansas & Texas track he took his own life in his hands and he knew it. On nearly every trail would be found posted by outlaws a small card warning certain deputies that if they ever crossed the dead line they would be killed. Reeves has a dozen of these cards which were posted for his special benefit. And in those days such a notice was no idle boast, and many an outlaw has bitten the dust trying to ambush a deputy on these trails.” -Oklahoma City newspaper article, 1907

Indian Territory was the most dangerous place for a U.S. Marshal to work then or ever. In the period before Oklahoma statehood, over one hundred marshals were killed in the line of duty. It helps to put that number in perspective: Since the US Marshals Service was created in 1789, more than 200 marshals have been killed in the line of duty. 120 of those were killed in the Indian and Oklahoma territories before statehood in 1907. That’s right, half of all the U.S. marshals ever killed were killed in the Twin Territories.

A man really had to have true grit to be a marshal at this time and in this place.

Bass Reeves had that grit in spades.

Reeves was likely the first African-American commissioned as a deputy U.S. Marshal west of the Mississippi River and was brought into the service by Judge Isaac C. Parker, aka the “The Hanging Judge.” Parker presided over the largest federal court district in U.S. history (74,000 square miles) and sentenced 88 men to be hanged during the course of his career. For more than half of his years on the bench, no appeals of his decisions were allowed. Reeves and Parker enjoyed a professional and personal relationship of great mutual respect.

It was a respect Reeves worked hard to earn.

Reeves stood 6’2 in a time when men were much shorter, and he had very broad shoulders and large hands. He was a giant among men. Such a large man needed a uncommonly large horse (“When you get as big as me, a small horse is as worthless as a preacher in a whiskey joint fight. Just when you need him bad to help you out, he’s got to stop and think about it a little bit.”). He rode the territories with two six-shooters, his trusty Winchester rifle, and a big black hat upon his head. Needless to say, Reeves cut an extremely imposing figure.

But it was his reputation more than his appearance that really struck fear in the hearts of the “bad men” of the territories. Contemporaries described Reeves as a “lawman second to none,” a man who was “absolutely fearless,” and a “terror to outlaws and desperadoes.” He was said to be the “most feared U.S marshal that was ever heard of in that country,” and his nickname was the “Invincible Marshal;” the undisputed king of narrow escapes, “at different times his belt was shot in two, a button shot off his coat, his hat brim shot off, and the bridle reins which he held in his hands cut by a bullet.”

Reeves was also know for his honesty, dogged persistence, and unswerving devotion to duty and the law. He always got his man; having arrested 3,000 criminals, he only once failed to nab the man he was after. He never shot a man when it wasn’t necessary and they hadn’t aimed to kill him first. And he never changed his policies or treatment of folks on the basis of race, ethnicity, or even familial ties; all were equal under the law. Not only did Reeves arrest the minister who baptized him, he also arrested his own son after the young man murdered his wife in a fit of jealously. None of the other marshals wanted the latter assignment, but Reeves simply strode into the Chief Deputy Marshal’s office and said, “Give me the writ.” Two weeks later, he brought in his son to be booked.

Oh, and he had an awesome mustache.

Reeves’ deeds and exploits are the stuff of Hollywood films, but they’re absolutely true and offer us several lessons in manliness.

Lessons in Manliness from Bass Reeves

It’s Never Too Late for a Man to Have a Second Act

Bass Reeves was born a slave in Arkansas in 1838. When the Civil War broke out, his white master joined the Confederate Army and took Reeves along to serve as his body servant. Reeves bided his time, until one night he saw an opening, laid out his master with his mighty fists, and took off for the hills a free man. He was taken in by the Keetoowah, an abolitionist sect of the Cherokee Nation.

When the war was over, he struck out on his own and settled with his family in Van Buren, Arkansas, making a good living as a farmer and horse breeder. He was the first black man to settle in Van Buren, and he built his family an eight room house with his own hands.

He started making some extra money by helping the U.S. Marshals with scouting and tracking and soon earned a reputation for himself as a man who knew what he was doing and could be relied upon.

He was commissioned as a Deputy U.S. Marshal in his own right in 1875, when he was 38 years old. During this time marshals were paid for the number of criminals brought in and the distance traveled in capturing them and bringing them back to court. With so many miles to cover in Indian Territory, and with his legendary effectiveness for tracking down wrong-doers, Reeves made a great living at his job. And so it was only as he was nearing 40 that he found his true calling.

Compensate for Weaknesses by Cultivating Signature Strengths

“My mom always said she heard that Bass was so tough he could spit on a brick and bust it in two!” -Willabelle Shultz, granddaughter of fellow marshal

Because he grew up a slave, Bass Reeves did not know how to read or write. Being an illiterate U.S. Marshal was highly unusual—the men needed to fill out forms and reports–but Bass got and kept his job by compensating for this weakness with other valuable strengths.

First, he could speak the Muskogee language of the Creeks and Seminoles, and he could also converse pretty well in the languages of the other Five Civilized Tribes. He took the time to get to know the tribes and their customs, and they respected him for it. His friendly and sterling reputation among Indians, blacks, and whites alike led folks to trust him and give him assistance and tips they didn’t feel comfortable sharing with other marshals.

Reeves knew Indian Territory like the back of his hand, and his scouting and tracking skills were second to none.

But his most notable strength was his prowess with firearms. He carried two big .45 caliber six-shooters and wore them with their handles facing forward. He employed the cross-handed draw, as he believed it was the fastest way for a man to grab his guns. And indeed, he was known as a man who could draw with lightning fast speed; numerous men tried to beat him, and 14 of them died in the attempt.

But unlike what you see in movies, cowboys in the West did not rely on their pistols; those were their back-up firearms. A cowboy’s weapon of choice was his trusty Winchester rifle, and that was the gun Reeves used most. But he was a proficient marksman with both weapons. Ambidextrous and always cool under pressure, Reeves could fire an accurate shot with pistol or rifle, with his left hand or his right. It was said he could draw “a bead as fine as a spider’s web on a frosty morning” and “shoot the left hind leg off of a contended fly sitting on a mule’s ear at a hundred yards and never ruffle a hair.”

Turkey shoot competitions were popular at territorial fairs and picnics, but Reeves was banned from entering them because he was too darn good. Once, when he saw 6 wolves tearing at a steer, he took them all out with just 8 shots from the back of a galloping horse.

The Mind Is Just as Powerful a Weapon as the Gun

“If Reeves were fictional, he would be a combination of Sherlock Holmes, Superman, and the Lone Ranger.” -Historian Art Burton

Despite Bass’ legendary strength and prowess with firearms, he didn’t simply go after criminals with guns and fists blazing. Rather, he took a far slower, methodical, and ultimately more effective approach. He was an intuitive and quick-thinking detective who often got his man from being smart and crafty.

Reeves was a master of disguise, a tactic he used to sneak up on unsuspecting outlaws. They would undoubtedly see a giant black man on a giant horse coming for them, so when Bass was closing in on a man, he would switch to a smaller ride, and he learned tricks from the Indians on how to look smaller in the saddle.

And often he would ditch the horse all together. For example, one time he dressed like a farmer and lumbered along in a ramshackle wagon pulled by old oxen. He drove the wagon close to a cabin where six outlaws where holed up, and as he passed their hide out, he pretended to get the wagon snagged on a large tree stump. When the outlaws came out to help this humble farmer, he coolly reached into his overalls, drew out his six-shooters, and placed the men under arrest.

On another occasion, Reeves was after two outlaws who were hiding out at their mother’s house. Reeves camped 28 miles away to be sure they didn’t see him coming or hear he was in the area. Then he ditched his marshal duds and stashed his handcuffs and six-shooters under a set of dirty, baggy clothes, flat shoes, and a large floppy hat into which he shot three bullet holes. Dressed like a typical tramp, Reeves sauntered up to the felons’ hideout and asked for something to eat, showing them his bullet-ridden hat and explaining how he had been shot at by marshals and was famished from having walked for miles to flee the law. Having ingratiated himself as a fellow outlaw, the men ate together and decided to join forces on a future heist. After everyone had fallen asleep for the night, Reeves crept up to the two outlaws and handcuffed them in their sleep, careful not to wake them. In the morning, Reeves bounded into the room and woke them up with his booming voice, “Come on, boys, let’s get going from here!” As the men tried to get out bed, they quickly realized they’d been had by crafty old Bass Reeves.

Be Reliable–The Details Matter

Even though he was a tough-as-nails badass, locals also remembered Reeves as a man known for his “politeness and courteous manner” and as someone who was “kind,” “sympathetic,” and “always neatly dressed.” He was also a man who took pride in getting the details right.

Reeves was unable to read or write and yet part of his job was to write up reports on his arrests and serve subpoenas to witnesses. So when he had to write a report, he would dictate to someone else and sign with an “X.” When he would get a stack of subpoenas to serve to different people, he would memorize the names like symbols and have people read the subpoenas out loud to him until he memorized what symbol went with what subpoena.

He took great pride in the fact that he never once served the wrong subpoena to the wrong person. In fact, many of the courts specially requested that their subpoenas be served by Reeves because he was so reliable.

Keep Cool. Always.

“Reeves was never known to show the slightest excitement under any circumstance. He does not know what fear is. Place a warrant for arrest in his hands and no circumstance can cause him to deviate. ” –Oklahoma City Weekly Times-Journal, 1907

Bass Reeves had an uncanny ability to stay calm and cool, even when he was in a really tight spot.

He found himself in that kind of tight spot while looking to arrest a murderer, Jim Webb, who was hanging out with posseman Floyd Smith at a ranch house. Reeves and his partner moseyed up, tried to pull the old, “we’re just regular cowboys passing through” trick, and sat down to get some breakfast. But the two men weren’t buying it and sat glaring at the marshals, pistols at the ready in their hands. An hour went by and Reeves and his partner still didn’t have an opening to make a move on the outlaws. But when Webb was momentarily distracted by a noise outside, Reeves jumped up, wrapped his large hand around Webb’s throat, and shoved his Colt .45 in the surprised man’s face. Webb meekly surrendered. Reeves’ partner was supposed to jump in and grab Smith, but he froze. Smith fired two shots at Reeves; he dodged them both, and with his hand still around Webb’s neck, he turned and took Smith out with one shot. Then he ordered his partner to handcuff Webb and called it a day.

Reeves was the target of numerous assassination attempts but he often saved his own neck by staying completely calm and in control. One time, he met two men out riding who knew who he was and wanted him dead. They drew their guns and forced him off his horse. One of the men asked if Reeves had any last words, and Bass answered that he would really appreciate it if one of them could read him a letter from his wife before finishing him off. He reached into his saddlebag for the letter and handed it over. As soon as the would-be-assassin reached for the letter, Bass put one of his hands around the man’s throat, used his other hand to draw his gun, and said, “Son of a bitch, now you’re under arrest!” The outlaw’s partner was so surprised he dropped his gun, and Reeves put both men in chains.

Another time, Reeves faced a similar situation; this time three wanted outlaws forced him from his horse and were about to do him in. He showed them the warrants he had for their arrest and asked them for the date, so he could jot it down for his records when he turned the men into jail. The leader of the group laughed and said,“You are ready to turn in now.” But having dropped his guard for just a second, Reeves drew his six-shooter as fast as lightning and grabbed the barrel of the man’s gun. The outlaw fired three times, but Reeves again dodged the bullets. At the same time, and with his hand still around the barrel of the first man’s gun, he shot the second man, and then hit the third man over the head with his six-shooter, killing him. All in a day’s work for Deputy U.S. Marshal Bass Reeves.

Build a Bridge

When Reeves was appointed a marshal by Judge Parker, the judge reminded him that “he would be in a position to serve as a deputy to show the lawful as well as the lawless that a black man was the equal of any other law enforcement officer on the frontier.”

Bass took this responsibility seriously.

Black law enforcement officers were a rarity in other parts of the country, but more common in Indian Territory and surrounding states like Texas. In fact, despite Hollywood’s depiction of the Old West as lily white, 25% of cowboys in Texas were African-American.

Because of the reputation Bass earned as a marshal who was honest, effective, and doggedly persistent–the Chief Deputy U.S. Marshal of the Western District, Bud Ledbetter, called Bass, “one of the bravest men this country has ever known”–more black marshals were hired in Indian Territory; a couple dozen were part of the service during Bass’ tenure. Nowhere else in the country could a black man arrest a white man. Bass had paved the way, and done one of the manliest things a man can do—build a bridge and a legacy for others to follow.

Sadly, when Oklahoma became a state in 1907, it instituted Jim Crow laws that forced black marshals out of the service. Despite his legendary record as a deputy marshal, Reeves had to take a job as a municipal policeman in the town of Muskogee the year before he died. But his shining example of manhood cannot so easily be passed over and still speaks to us today.

Source: Black Gun, Silver Star: The Life and Legend of Frontier Marshal Bass Reeves by Art Burton