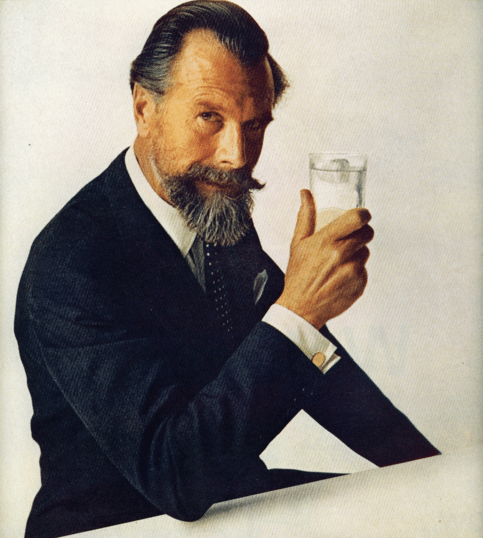

Editor’s note: In writing today’s piece on the benefits of quitting caffeine, I was reminded of the following passage from How to Live the Good Life by Commander Edward Whitehead. A British Royal Navy Officer, WWII veteran, and the President of Schweppes (USA), Whitehead had accumulated a bevy of wisdom on how to live better (he articulated the idea of there being 3 characteristics of an educated man), and I enjoyed his challenge to consider whether one’s crankiness is truly temperament, or might be due to what one is regularly imbibing. I know when I first read it, I certainly recognized myself in the salesman he describes!

____

There is hardly a soul who would stand up to make a case for poor health or the joys of feeling terrible, yet eight out of ten of us live our lives as if we’re afraid good health might sneak up on us and do us in. Look around any office, look at a random sampling of shoppers in a supermarket, and you will see paunchy, pallid, tired-looking people who probably eat the wrong food, drink and smoke too much, exercise rarely and, while not ill, are not well either. They drift into that miasma of stimulants, sedatives, snack foods, nicotine, late nights and slow wits that dulls the texture of each day; the victim never notices that his body and mind are working at half speed while his daily routine carries him along at an ever more frenetic pace.

Some people are capable of persuading themselves that they aren’t abusing their health when they are, or that they can feel wonderful if they just use their willpower to overlook their own symptoms. I am all for positive thinking, I believe in the power of mind over matter, but self-deception is something else again.

I know a man who owns a small manufacturing company in Manhattan. A self-made man, he has turned his father’s store-front cabinet shop into a thriving concern with some sixty employees. The company provides custom cabinet work and office design to corporations as far afield as Atlanta and Houston. This man is a young, vigorous, high-powered salesman who throws himself into each workday with total abandon. He has a bluff charm that even his competitors find ingratiating. If you were to stop by his place of business, however, you would hear him before you met him. His temper is legendary. His generous-spirited moments, his kindness to employees who have troubles at home, his willingness to discuss on-the-job problems, are the fine qualities squeezed in between bouts of shouting that curl the hair of the unwary visitor waiting in an anteroom.

The storm passes quickly, one learns. Probably the man will stop by the desk of the poor wretch he was castigating half an hour before and apologize. “It doesn’t mean anything; it’s just the way he is,” says an abashed office worker, spotting the visitor’s anxious face. “It’s his temperament.”

If you were to spend some time with this man and observe his twelve- or fourteen-hour days on the job, his passionate love for his business that takes priority over every other interest in his life, even over a family for whom he cares deeply, and certainly over his own physical well-being, you would pause to wonder.

If you were to ask him about his health, he would say he felt fine, although of course he could lose a few pounds. (His doctor would say at least thirty.) He would remark that his wife, whom he loves very much, is unable to persuade him to take much time away from work. He could now afford a boat and a ski house, but would find little time to enjoy them. He would tell you, however, that on those rare occasions when he and his family spend a week in Vermont, he skis with all the single-mindedness that during the rest of the year he saves for business. A man of high energy and good natural physical co-ordination, he spends eight hours at a stretch on the slopes; even when he’s worn out he wants to try one more run.

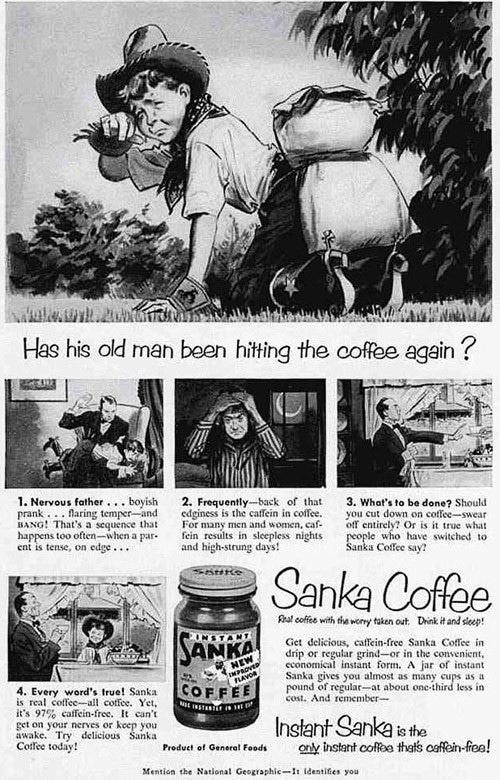

Needless to say, his family and his friends worry about him. They too feel that it’s his “temperament” that drives him on and on without letup, and that his “temperament” accounts for his mood swings. However, I would reserve judgment on the nature of his temperament until several days after he has unplugged his office coffee pot. He habitually drinks a dozen cups of coffee a day, he says, as casually as if everyone does the same. I watched him eat lunch — an apple, a doughnut, a pastrami sandwich at his desk, or eaten in transit from one office to another as he continued his work. In one hand he always held his mug of coffee.

According to a report cited in The New York Times a year or so ago, coffee isn’t bad for you — if you limit yourself to no more than one or two cups a day. In fact, coffee may even have some therapeutic value — it’s a stimulant and there is medical evidence to suggest that a cup of coffee can alleviate certain types of headache. (One of the leading proprietary drugs contains caffeine as a “secret ingredient” against headache.) For most people, a cup of coffee is one of life’s innocuous pleasures. But for those who drink more than one cup or two a day, coffee is somewhat toxic. Before many more cups are consumed, symptoms appear like those associated with certain types of mental illness. Palpitations, anxiety, cold sweats, hysteria, depressions, blackouts, and violent mood swings are common among those overdosing on coffee, or on other sources of caffeine such as tea or cola drinks. The strain on the heart and the circulatory system is incalculable. The metabolism is unbalanced, and the mind functions erratically.

If this man were to cut back gradually on his coffee intake, even while continuing to violate every other rule for good health, he would no doubt experience such a change in his “temperament” that his associates would hardly recognize him. (A heavy coffee drinker should decrease his intake over a period of time to prevent withdrawal symptoms.)

Of course, our friend will not make this change in his diet, because he has persuaded himself that his actions have very little do with his physical condition. He sees no cause and effect between his habits and the way he feels. He thinks he needs all those cups of coffee to get him in shape for business, and although he is an intelligent, quick-witted man, nothing would convince him that because of them he loses his best employees, alienates clients, works ineffectively, is a burden to his family, and that he may not live long enough to enjoy the fruits of his labors.

Be sure to listen to our podcast all about how caffeine both hurts and helps us: