One technique people have used for centuries to improve themselves is the making of resolutions.

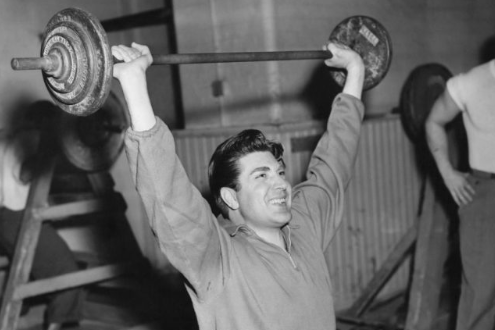

At the start of the year, or at any time throughout it, someone may resolve to lose ten pounds, quit smoking, or write in their journal each day.

But of course, as endlessly pointed out, most such aims fail to be achieved.

According to some estimates, only 8% of people keep their New Year’s resolutions. Those abysmal numbers are likely about the same for resolutions that are initiated at other times, too.

Given this failure rate, should you, as many people do, decide that resolutions are pointless and give up on making them altogether?

No. Resolutions can work. You just have to make better ones. Unbreakable ones.

Gandhi and a 19th-century Prussian prince named Hermann von Pückler-Muskau can show us how.

The 3 Characteristics of Unbreakable Resolutions

You likely know Gandhi. Hermann von Pückler-Muskau, probably not.

Pückler-Muskau was a colorful character who engaged in pursuits typical of a Prussian nobleman — painting, attending the theater — and yet also lived a far more interesting, daring, and adventurous life than his aristocratic peers. He went to battle as a cavalry officer, became a preeminent landscape designer, tramped around Europe by foot, explored North Africa, and wrote books about his travels.

While he and Gandhi led very different lives, a group of psychologists at Alberta’s MacEwan University — Russell Powell, Rodney Schmaltz, and Jade Radke (hereafter referred to as PSR) — make the case that they had very similar approaches to creating and keeping resolutions. Both men almost always followed through in doing what they said they’d do.

In studying the lives of the Indian statesman and the Prussian prince, PSR determined that their success in consistently keeping their resolutions wasn’t a matter of willpower. It didn’t primarily rest on the men’s personal characteristics, but rather on the characteristics of the resolutions they made. Specifically, PSR posit that the following three qualities are what take a regular resolution, and make it nearly unbreakable:

1. Unbreakable resolutions are highly distinctive.

PSR note that for both Gandhi and Pückler-Muskau, there was “a ‘bright line boundary’ between unbreakable resolutions and other types of resolutions, promises, and intentions.”

Unbreakable resolutions differ from regular resolutions in carrying real existential and spiritual stakes.

Gandhi called his resolutions vows, and would employ them when he decided to fast from food or abstain from sex. For him, resolution-making was different from mere goal-making. It was a spiritual practice. Serious stuff, not something to be trifled with.

Pückler-Muskau called his resolutions “grand expedients.” And like Gandhi, he imbued these commitments with spiritual stakes. When the prince formulated a grand expedient, he considered the “welfare of his soul” to be on the line. Consequently, he only made them carefully and thoughtfully.

2. Keeping the resolution is itself highly reinforcing, while breaking the resolution is highly aversive, regardless of the specific target of the resolution.

Because Gandhi and Pückler-Muskau invested their resolutions with real weight, following through on them was greatly rewarding, while shirking them was greatly distressing. They couldn’t bear to see themselves as men who didn’t keep their promises. The prince described his horror at the thought:

If I were capable of breaking it after such mature consideration, I should lose all respect for myself — and what man of sense would not prefer death to such an alternative? For death is only a necessity of nature, and consequently not an evil . . . But a conviction of one’s own unconquerable weakness is a feeling which must embitter the whole of life. It is therefore better, if it comes to the struggle, to give up existence for the present with a feeling of inward triumph, than to crawl on with a chronic disease of the soul.

3. Unbreakable resolutions are viewed as a device or tool that, if carefully maintained, can be employed to attain a variety of high-valued outcomes in the future.

Another element that motivated Gandhi and Pückler-Muskau to keep their resolutions was the way in which they viewed resolutions as tools, or as the latter described them, “weapons.” And like all tools, they could either be honed and strengthened or neglected and ruined.

Both men understood that each time they kept a resolution, it would make keeping resolutions easier in the future; conversely, each time they broke a resolution, it would be easier to break a resolution down the line. Be consistent with the former, and they could accomplish their goals and life’s purpose; engage in enough of the latter, and they might give up on resolutions entirely, thereby forever losing an important tool of personal development.

How to Make Unbreakable Resolutions

While the research on the efficacy of unbreakable resolutions is still preliminary, what’s been done so far “indicates that some individuals find them to be highly effective,” and PSR has formulated several guidelines on how they are best put into practice:

At the start of the day (or the night before), in some highly distinctive way, make an unbreakable resolution to accomplish at least one task that day that you might not otherwise accomplish.

The most important of an unbreakable resolution’s three characteristics is its distinction from a run-of-the-mill intention — the sense that your soul and self-respect are on the line, and that it must therefore be accomplished at all costs.

You might not think you can simply decide to invest a resolution with existential stakes, but you’d be surprised with how well this works.

Be very thoughtful about the unbreakable resolutions you make. Unless Pückler-Muskau was completely convinced of the necessity of taking some action and of his own commitment to it, “the mysterious formula is not pronounced.” Once you do make a resolution, decide that keeping it is a matter of sacred honor.

Know your limits; start small.

Both Gandhi and Pückler-Muskau believed that vows or grand expedients should only be made that 1) fit your nature, and 2) are within your limits.

Wrote the prince:

Every man must however manage himself according to his own nature; and as no one has yet found the art of making a reed grow like an oak, or a cabbage like a pineapple, so must men, as the common but wise proverb has it, cut their coat according to their cloth. Happy is he who does not trust himself beyond his strength!

Gandhi likewise warned of taking “vows that are beyond one’s capacity [which] would betray thoughtlessness and loss of balance.” It was better instead to “take easy and simple vows to start with and follow them with more difficult ones.”

To begin your use of unbreakable resolutions, employ them in tackling the annoying tasks of “life admin” — doing taxes, filling out forms, answering emails. Pückler-Muskau did so with great success:

[A] grand expedient is of admirable use in trifles. For example, to fulfil tedious, irksome duties of society with the resignation of a calm victim — to conquer indolence so as to get vigorously through some long deferred work — to impose upon oneself some wholesome restraint, and thus heighten one’s enjoyment afterwards — and many, many more such cases, which this occasionally sublime, but generally childish life presents.

Recognize that obstacles might arise that necessitate abandoning a resolution; in other words, resolutions can be conditional. But make them rare exceptions.

While you should do everything you can to keep your unbreakable resolution, both Gandhi and Pückler-Muskau understood that exceptions, in very rare circumstances, could be made.

The former thought that “a vow can be made conditional without losing any of its efficacy or virtue,” and that breaking a vow might be justified if, for example, “one is travelling or sick.”

Pückler-Muskau was a bit more stringent with his exceptions and allowed “nothing short of physical impossibility” to stop him.

Impose a penalty on yourself if you inadvertently break a resolution without sufficient justification.

If you do break a vow or grand expedient, there needs to be some sort of punishment or penance done to reinforce the solemnity of unbreakable resolutions and to restore your own sense of credibility.

For Gandhi, this idea was based in his Hindu religion. “If he forgets his vow at any time,” the ethicist wrote, “he should do prayaschitta [penance or atonement] and remind himself of the vow.”

For a Christian, the breaking of an unbreakable resolution might require repentance/confession.

For the non-believer, PSR suggests “mak[ing] up for the violation by doing something effortful or unpleasant. This could involve something as simple as taking a cold shower or not drinking coffee for a day.”

But remember, the goal is to never fail on following through with an unbreakable resolution because every time you do, you increase the likelihood of failing again.

In addition to using the four guidelines above, PSR also recommends not telling other people about your unbreakable resolutions, at least at first. Instead, stay quiet about them, and get to work. There’s power in keeping goals to yourself.

They also recommend writing your unbreakable resolution in a special notebook or placing a moral reminder about it around your house. The idea is to keep it at the front of your mind as much as possible.

As you make and keep unbreakable resolutions, you’ll not only find yourself making progress as a man, but will start feeling as Pückler-Muskau described:

I find something very satisfactory in the thought, that man has the power of framing such props and such weapons out of the most trivial materials, indeed out of nothing, merely by the force of his will, which hereby truly deserves the name of omnipotent.