Your boss invites you to the country club to play a round of golf with him and other important higher ups. You’ve never stepped foot in a country club before, and haven’t played any golf beyond putt-putt.

You’re hoping to graduate early and decide to take an advanced class that’s required for your major, even though you haven’t taken the recommended prerequisites for the class. It’s only the first week, but you’ve only really understood 10% of what the professor’s been saying.

You put “Excel” under your list of skills on your resume because you once created a super simple table to chart your exercises. After you’re hired, your boss asks you to do some more advanced Excel functions, and you’ve been staring blankly at the screen for an hour.

A rich friend has invited you to a charity ball in which the guests make about 10 times as much as you do. You feel a little silly as you pull up and give the keys to your 95 Honda Civic to the valet.

You’re a high school sophomore, and your brother invites you out with him and his graduate student friends. As they talk about their favorite books, most of the conversation goes over your head.

You move to a foreign country and only know how to ask, “Where is the library?”

Every man will experience a scenario like those outlined above at least once in his life. It’s called being out of your depth, and it means that you find yourself in a situation where your skill or knowledge isn’t on par with what’s needed and/or with the rest of the people in the group.

Sometimes out of our depth situations are our own fault. We fudge a little and lead someone on to think we’re more comfortable or experienced with something than we actually are, and when they call on that expertise, our noob-ness is revealed. Those kinds of situations are avoidable with a little humility and honesty.

But oftentimes we’re just thrown into situations where we find ourselves out of our depth. Unforeseen problems at work or a friend’s invitation can put us there. They also often spring up on us while pursuing adventures (they wouldn’t be adventures if they didn’t push you outside your comfort zone after all).

Regardless of how you got into the jam, you’re going to want to make the most of it and minimize the damage.

Being out of your depth can be incredibly nerve-racking, as these kinds of situations are often ones where you cannot easily ask for help without compromising your position or missing out on an opportunity.

But it is possible to quell the stress, and handle an out of your depth situation like a pro. And so today we turn to a pro for advice on how to do that. A professional con man that is.

Frank Abagnale, whose autobiography, Catch Me If You Can, became a popular film, engaged in some of the most clever and literally high flying swindles of all time. Between the ages of 16 and 20, this high school dropout traveled all over the world posing as a pilot for Pan Am, impersonated a chief resident pediatrician at a Georgia hospital, passed the bar and became a prosecutor for the Louisiana attorney general, taught sociology as a college professor, and forged two million dollars in checks.

Now, I’m by no means advocating that you should follow his path and become a con man! But a guy who can sit in the jump seat in a plane’s cockpit, pretending to be a pilot and chatting comfortably with the crew, knows a thing or two about fearlessly dealing with being out of your depth. The man had cojones of steel, and the techniques he used to get away with his elaborate capers can be utilized by any man who’s looking to get out of a very legal–but embarrassing–pickle. Here are 6 of them.

1. Relax and Project Confidence

“When the guard turned to confront me, I was combing my hair with my fingers, my hat in my left hand. I didn’t break stride. I smiled and said crisply, “Good evening.” He made no effort to stop me, although he returned my greeting. A moment later I was inside Hangar 14…I hesitated in the lobby, suddenly apprehensive. Abruptly I felt like a sixteen-year-old and I was sure that anyone who looked at me would realize I was too young to be a pilot and would summon the nearest cop. I didn’t turn a head. Those who did glance at me displayed no curiosity or interest.” -Frank Abagnale. Catch Me If You Can

When you’re in a situation where you feel like you’re out of your depth, nervousness and even panic can set in—your heart races; your palms get sweaty. The feeling of being out of place consumes your thoughts. As you look around the room, it feels like your inner dialogue is being broadcasted from your forehead, and that everyone else is focusing in on you.

But as Abagnale discovered, people are far less observant and attentive than you’d think; folks aren’t tuned in to looking for differences, absences, and discrepancies.

There was a study done once on a college campus in which a researcher would stop and talk to a student. In the midst of the conversation, two workers would rudely walk between the pair while carrying a large door. As the workers passed in-between them and the door obscured the student’s view, the first researcher quickly and furtively ducked out, and a new researcher stepped in. When the door passed by, the student was standing in front of a brand new person, and yet the majority failed to realize it!

So the next time you’re at an event where you feel like everyone is staring at you, try to relax and realize that people probably aren’t paying attention to you. Abagnale found that if he strode confidently and purposefully wherever he wanted to go, people were unlikely to question him at all. He acted like he belonged, so people assumed that he did.

Of course, he also always made sure to…

2. Look the Part

“The transaction also verified a suspicion I had long entertained: it’s not how good a check looks, but how good the person behind the check looks that influences tellers and cashiers.”

“I was always accepted at par value. I wore the uniform of a Pan Am pilot, therefore I must be a Pan Am pilot.”

Abagnale found that there was great power in an uniform. This was back in the day when flying was quite glamorous, and wherever he went in his Pan Am pilot’s get-up, people instantly afforded him trust, respect, and admiration.

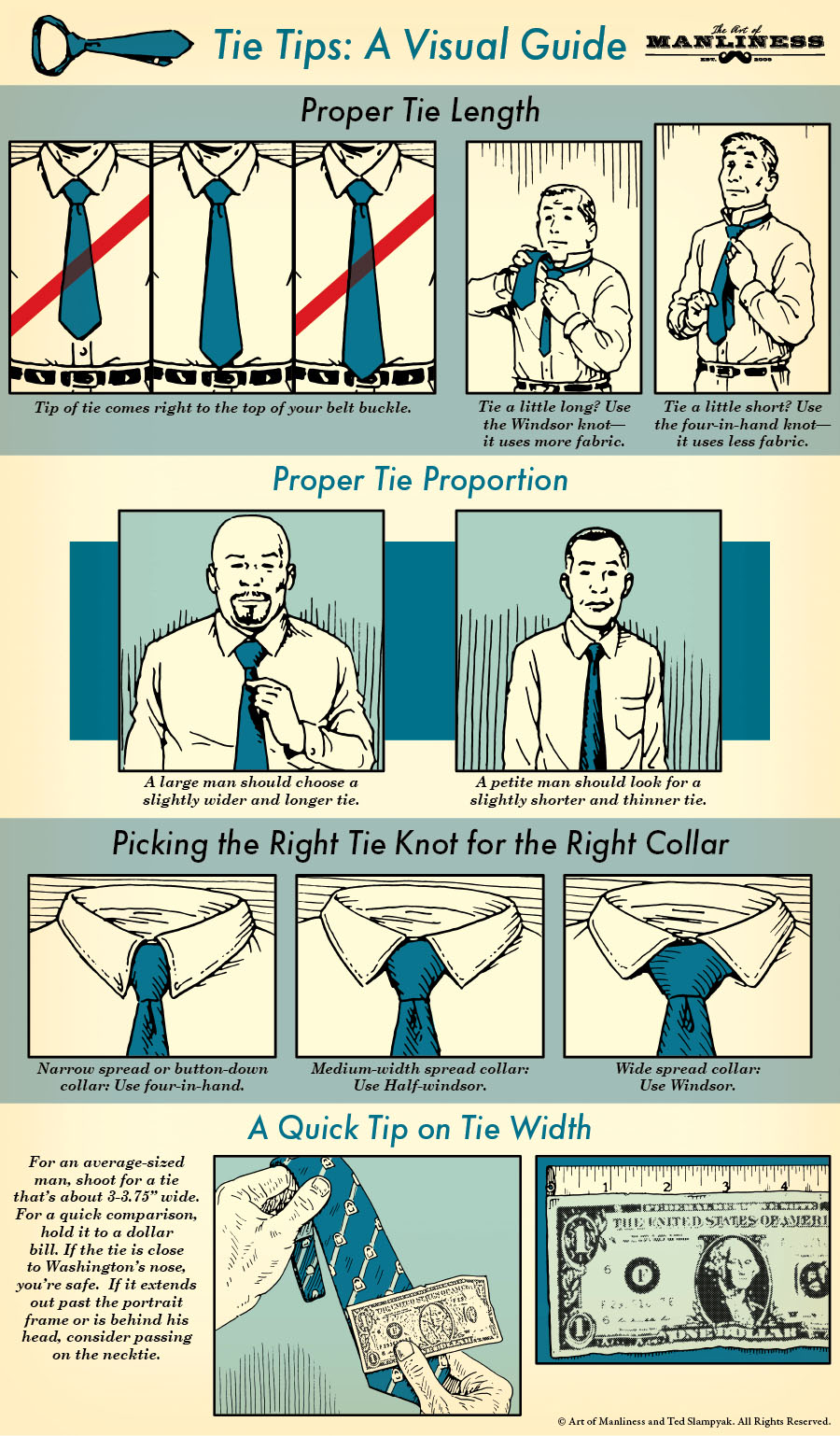

While not every job and situation calls for an actual uniform, every event does have a standard of dress, and by adhering to it, you’ll automatically seem more like a guy who knows what’s he’s doing. First impressions are crucially important and people use them to glean a lot of information about you. If you show up in jeans and a t-shirt to a swanky party, or a three piece suit to a casual workplace, people will immediately peg you as a guy who’s not quite on the level.

Additionally, when you’re dressed appropriately, and you feel like you look good, your confidence goes up, and this effect is only compounded as people treat you with more respect. Abagnale’s pilot’s uniform changed the way people treated him, which greatly increased how comfortable he felt with the role he was playing.

3. Play Catch-Up Like a Mad Man

“Obviously, I reflected as I left the building, I was going to need more than a uniform if I was to be successful in my role of Pan Am pilot. I would need an ID card and a great deal more knowledge of Pan Am’s operations than I possessed at the moment. I put the uniform away in my closet and started haunting the public library and canvassing bookstores, studying all the material available on pilots, flying and airlines.”

If you’ve been thrown into a situation where you don’t have the skills or knowledge to perform up to par, then you’re going to need to play catch-up every spare second you get. Use your lunch break and your evenings to research everything you need to know to perform your new role or pass the class. If there’s an event on the horizon where you worry you might be out of your depth, then you have the lucky opportunity to plan ahead and bone up before attending.

Abagnale didn’t go into his impersonations by the seat of his pants; rather, they were the result of meticulous and thorough planning and research. He used the same study-intense approach he took in learning about being a pilot with all of his impersonations. When he was pretending to be a pediatrician, he spent countless hours reading books and medical journals, and he carried around a pocket dictionary; whenever an intern or nurse used a term he wasn’t familiar with, he’d go hide in the linen closet, find the word, and memorize its meaning. When he became a college professor, he audited classes to see how other teachers practiced their craft and studied the textbook rigorously.

But there was always a lot of information Abagnale couldn’t find in books, such as the lingo and slang that pilots or doctors used. So he employed other methods of information gathering as well. For example, when learning the ins and outs of flying for Pan Am, he called up the airline, and posing as a high school newspaper reporter, asked to speak to a pilot, whom he then peppered with a myriad of questions about the job. You don’t have to make up an alias to fish for information, however. Just weave casual questions–questions that seem like the “I’m just curious variety”–into your conversations with others.

4. Take Notes

“I kept a notebook, a surreptitious journal in which I jotted down phrases, technical data, miscellaneous information, names, dates, places, telephone numbers, thoughts, and a collection of other data I thought was necessary or might prove helpful.

It was combination log, textbook, little black book, diary and airline bible, and the longer I operated the thicker it became with entries…The names of every flight crew I met, the type of equipment they flew, their routine, their airline and their base went into the book as some of the more useful data.

Like I’d be deadheading on a National flight.

‘Where you guys based out of?’

‘Oh, we’re Miami-based.’

A sneak look into my notebook, then: ‘Hey, how’s Red doing? One of you’s gotta know Red O’Day. How is that Irishman?’

All three knew Red O’Day. ‘Hey, you know Red, huh?’

Such exchanges reinforced my image as a pilot and usually averted the mild cross-examinations to which I’d been subjected at first.”

No matter how much direct or indirect research you do, don’t rely on your memory alone to store all that information. Instead, jot down notes that might prove useful down the line. If there’s some duty at your new job that you should know how to do, but don’t, you can easily get away with saying to your boss, “You know I used to be great at this, but it’s been awhile since I did it. Could you refresh my memory?” He’ll be happy to do so the first time, but if you have to keep asking how to do it again and again, he’ll start to get annoyed. So when he shows you something, write it down so you can refer to it later without bothering anyone.

You can write down people’s names and their interests as well, so that when you know you’ll be attending an event with them, you can study the notes, get their name right, and have material to initiate conversation and build rapport with.

5. Turn on the Charm

“I learned early that class is universally admired. Almost any fault, sin or crime is considered more leniently if there’s a touch of class involved.”

Abagnale treated everyone he dealt with–the tellers, stewardesses, students, and interns–with generous amounts of politeness, charm, and class. His charm staved off suspicion that he wasn’t who he said he was, and made them very willing to help him.

“If I was going to fake out seven interns, forty nurses and literally dozens of support personnel, I was going to have to give the impression that I was something of a buffoon of the medical profession.

I decided I’d have to project the image of a happy-go-lucky, easygoing, always-joking, rascal who couldn’t care less whether the rules learned in medical school were kept or not.”

He also found that self-deprecation can be an important tool of charm. A little wink-wink bumbling. While he was pretending to be a doctor, he’d let his interns make all the decisions, which won them over. And when he made a mistake, they’d say, “Oh, stop joking doc!”

If you’re an irritating boor who’s messing up all the time, you’re going to get the boot. But if you’re polite and good-humored, people will give you the benefit of the doubt and lots of second-chances.

6. Close Your Yap and Observe

“I didn’t do a lot of talking initially. I usually let the conversations flow around me, monitoring the words and phrases and within a short time I was speaking airlinese like a native. La Guardia, for me, was the Berlitz of the air.”

The best thing you can do when you’re in a situation where you’re out of your depth is to be extremely conservative with both your actions and your words. Say little and listen a lot. This gives you a chance to observe how other people are doing and saying things. If you’re at swanky dinner with a full place setting, and aren’t sure which utensils to use, wait a few moments after each dish is served, and casually watch what other people pick up. Then follow suit.

Keeping your mouth shut while you observe has two advantages. As the famous saying goes: “It is better to keep silent and be thought a fool than to speak and remove all doubt.” If you find yourself engaged in a conversation that is largely going over your head, it’s best not to throw out something like, “Oh, I loved the Great Gatsby! But I was so sad when they shot that rabid dog at the end.” That people will remember. On the other hand, if you don’t say much, there’s a chance they’ll think you’re not talking because you don’t know much about the subject, but there’s also a chance they’ll simply think you’re the smart, silent type. Given the fact that you’re likely to be dealing with a conversational narcissist these days, just ask him lots of questions (“Why do you think that?), and they’ll not only be bound to come to the latter conclusion, they’ll be rather charmed.

Have you ever found yourself in a situation where you were out of your depth? How did you handle it? Share your stories and advice with us in the comments!