Last week we began a three-part series on how to overcome shyness — a feeling of social anxiety and discomfort that can hold us back from forming warm relationships, reaching our goals, and just enjoying life in general. In the last post, we explored the nature of shyness including its roots and symptoms. We ended by discussing some of the causes of shyness, and noted that faulty thinking about socializing is the most significant one. Today we will examine in greater detail the self-sabotaging mindset that leads to shyness.

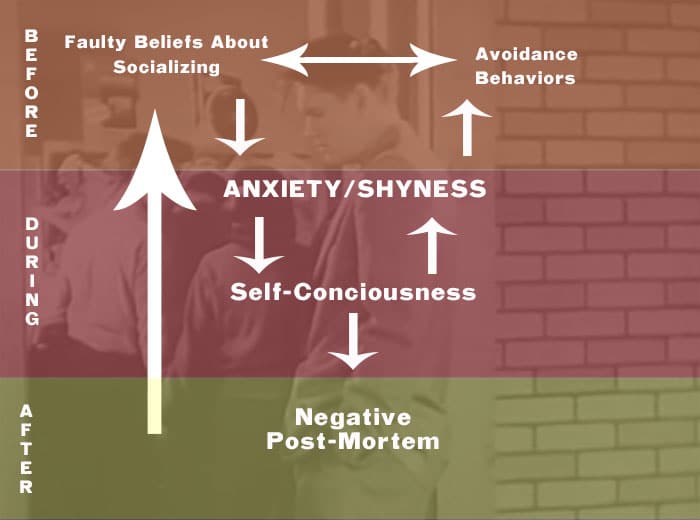

Framing our social interactions with faulty beliefs contributes to shy feelings and behaviors in two ways. First, faulty thinking makes social encounters seem more stressful and threatening than they actually are. So much so, that the shy individual will feel a sense of dread in simply contemplating these interactions, and will avoid socializing in order to prevent imaginary harms from befalling them. Second, the anxiety created by negative, misguided cognition will often trigger acute self-consciousness during social encounters. This self-consciousness, as we will see, perpetuates a cycle of shy feelings and behavior that prevents people from successfully and comfortably socializing with others.

What are the common faulty beliefs, errant assumptions, and negative cognitive biases that sap our confidence and torpedo our social interactions? Let’s now take a look at the different ways a self-sabotaging mindset manifests itself before, during, and after social interactions.

The Faulty Beliefs and Behaviors That Increase Anxiety/Shyness Before a Potential Social Interaction

Faulty, negative thoughts in anticipation of social interactions can create a feeling of stress and anxiety that leads shy people to avoid such encounters when they can. Shy people will often skip an event, leave a party early, or abruptly break off a conversation in the worry it might soon take an awkward turn.

But avoiding socializing creates a paradox: while it decreases your anxiety in the short-term, it increases your shyness in the long-term. The more you try to avoid socializing, the more your anxiety about it intensifies, as you never give yourself a chance to see that interacting with others isn’t as scary as you think it is. You never get the chance to face your nerves and learn how to manage them.

Not only do so-called “avoidance behaviors” actually increase anxiety, they can also make you feel more self-conscious, which, as we’ll see, only perpetuates your feelings of shyness: “There I go again leaving the party early. I’m sure everyone noticed.”

Here are some of the false beliefs that create an unreasonable sense of dread before a social situation even occurs and lead to avoidance behaviors:

The belief that there’s only one way to socialize. Shy people sometimes think that they have to be extroverted and gregarious to be adept at interacting with others. But those who do a lot of listening, interspersed with great questions, are often equally prized as companions.

The belief that if you’re not amusing or incredibly fascinating, people won’t like you. Having a variety of interests, being well-read, and keeping up with the news all helps one in being a good conversationalist, but you don’t necessarily have to be a hilarious world traveler to be likable. I have friends who aren’t what I’d call amusing or super engaging, but I like them nonetheless because they have other traits that I admire and respect, like being loyal and down-to-earth.

The assumption that “If others want to talk to me, they’ll let me know.” In reality, people oftentimes get so caught up in the moment that socializing with others isn’t even on their radar. Or they’re also shy and are nervous about introducing themselves. Sometimes you have to take the initiative to make contact.

The belief that you’ll never get a second chance to make a first impression. This is a popular maxim, and there’s certainly truth to it. People size up whether they’ll like you within a minute of your meeting, and a bad first impression can lose you a chance at a new friend/girlfriend/business contact. Yet this pressure can lead you to continually postpone introducing yourself, waiting for the perfect, most opportune time — when you think you look good and feel confident and she seems especially receptive – that never comes. It’s better to relax a little, and just go ahead and introduce yourself. More often than not, even if the first encounter is a little awkward you’ll get the chance to recover and show people a better side of yourself the next time around.

The tendency to catastrophize. This is the belief that if some social encounter goes wrong, it will be the end of the world – an utter disaster! Yet if you probe someone who feels this way with a question like, “What’s the worst that can happen?” they often can’t come up with an answer beyond, “I’ll feel embarrassed.” As we talked about last time, social rejection triggers the primal survival part of the brain, as being accepted used to be essential for staying alive. But these days, a brush off doesn’t mean you’re destined to die alone on the savanna. It actually won’t have any effect on you whatsoever, except for what you allow yourself to feel and think about the encounter.

The tendency to draw overly general and personal conclusions from one’s missteps. This is also known as “me/always/everything” thinking. A shy person with a me/always/everything mindset automatically believes that when a social encounter goes less than ideally, he is the one who caused the problem (me), that he invariably makes social encounters awkward (always), and that his social faux pas undermine all aspects of his life (everything).

If the shy person were to actually sit down and think things through, he’d likely discover that oftentimes it’s not his fault when a social encounter goes awkwardly; it can be the other person’s miscues that are to blame or perhaps a distraction in the environment made talking difficult. He’d also see that there are times when he does successfully navigate social situations; our minds are biased towards ruminating on things that go awry, while taking little notice of all the times things go smoothly! Finally, he’d realize that just because a few social encounters are bumpy, it doesn’t mean the rest of his life will suck.

Here’s an example of a shy person using me/always/everything thinking, and how such faulty assumptions might be countered:

Me: “Man, Grace didn’t call back. I must have said something that upset her or made me look like a doofus.” (The reason that Grace didn’t call back could be due to a whole bunch of factors that don’t involve you: she could be busy at work or in the hospital; maybe she lost your phone number; or Grace could be shy herself and has been waiting on you to call her.)

Always: “I always make myself look like an idiot in front of others. What’s the use in even trying to talk to people?” (Is this really true? Sure, maybe you did do something that was a bit awkward in front of Grace, but there are plenty of times when you interact with others without a hitch, like at work, church, or with your friends. Don’t discount the positive! You’re more capable than your negative brain thinks you are!)

Everything: “I’m such a loser.” (You’re a loser just because of one bad social encounter? That’s probably not true. You may have a good job and are excelling at it. You’ve got a few close friends that are with you through thick and thin. You have a hobby that you really enjoy. You have a roof over your head. Etc., etc.)

When a shy person gives free rein to me/always/everything thinking, the thought of engaging socially with others seems so fraught with risk to their psyche and self-worth, that it feels best to opt out of it altogether.

Faulty Beliefs and Behaviors That Increase Anxiety/Shyness During a Social Interaction

The types of negative thoughts outlined above can create anxiety/shyness about a pending social engagement and the desire to avoid such events. At those times when a social encounter cannot be skipped, this premeditated stress can then be compounded by certain faulty beliefs you engage in while you’re interacting with someone.

Unfortunately, when we start feeling anxious, our focus shifts inwards and we become acutely self-conscious. This self-consciousness just leads to more anxiety, which leads to us feeling more and more shy. Here’s what contributes to this negative cycle:

Extreme self-awareness. Freud argued that shy people are narcissists. That seems harsh, but in a sense he was quite right. While shy people aren’t vying to be the center of attention amongst a group of people (the thought of doing so would be petrifying), they are the center of attention in their own minds.

Shy and socially anxious people are extremely self-conscious. All they think about is themselves: How do I look? Was that joke funny? Can they tell I’m nervous? Do they like me? Did I say the wrong thing?

When shy people begin to experience the symptoms of anxiety and worry like feeling hot and sweaty, having trembling hands, stuttering, or drawing blanks before speaking, they turn inward and begin concentrating on these symptoms instead of focusing on the person with whom they’re interacting. Oftentimes after they part ways with someone, they’ll kick themselves for not asking him or her more questions. They couldn’t remember to be interested in the other person, because they were so busy thinking about themselves!

The more you pay attention to how awkward and anxious you’re feeling, the more self-conscious you feel, which makes you act more awkward and anxious, and the cycle continues. Self-consciousness keeps our shy feelings going and reinforces in our minds that socializing is scary or at a minimum awkward.

Luckily, just because we’re thinking a lot about ourselves, and we think everyone is noticing our “slip-ups” and nervousness, this is usually not at all the case as we’ll now see.

The belief that people are paying more attention to you than they actually are. As Nicholas Epley notes in his book Mindwise, mindreading is something all humans do on a regular basis. Our ability to read minds makes social interaction possible; it’s how we figure out if someone is annoyed with us even if they don’t explicitly say so, and how we discern the meaning behind coy smiles or raised eyebrows. While we’re pretty good at mindreading, we sometimes make mistakes. This is especially true if you’re shy, as your anxiety-induced negativity bias leads you to make faulty assumptions as to what other people are actually thinking and feeling.

As we just noted, shy people retreat inward and focus on their anxious feelings. But they then flub at mindreading by assuming that others around them can notice how nervous or shy they feel and that others are judging them negatively for it.

But here’s the reality: your sweaty palms and nervousness are probably not observable. Even if your shy symptoms were apparent, most people are so caught up in their own selves that they don’t even notice. And if your symptoms did catch someone’s attention, they probably won’t give much thought to it at all and will move on to thinking about or doing something else.

This isn’t just comforting talk to make shy folks feel better; studies on the so-called “spotlight effect” back-up the fact that people pay much less attention to you than you think. In one study performed at Cornell, researchers had students put on t-shirts with a giant, smiling Barry Manilow head pasted on the chest and then had them knock on a door of a classroom filled with a bunch of other students filling out questionnaires. The student wearing the Manilow tee had to go to the front of the class and talk to the researcher. To draw as much attention to the t-shirt wearer as possible, the researcher told them to sit down, but right before they sat down, they were instead told to leave. The researchers hypothesized that because the students were wearing a cheesy t-shirt they would feel the spotlight effect especially strongly during this awkward moment, and would believe that all eyes were on them.

This turned out to be the case: when the researchers asked the students who had worn the Manilow t-shirts to estimate how many people noticed their shirt, they guessed about half. Yet when the researchers surveyed the classroom about the Manilow model, only 25% of them recalled the tee. As David McRaney, author of You Are Not So Smart, notes, “In a situation designed to draw attention, only a quarter of the observers noticed the odd clothing choice [emphasis mine].”

Basically, the mindreading conclusions shy people commonly draw are exaggerated: people are simply not paying as much attention to you as you think.

Faulty Beliefs and Behaviors That Increase Anxiety After a Social Interaction

Unfortunately, the negative reinforcement of self-consciousness doesn’t stop when the social engagement is avoided or awkwardly endured. Instead, it is often further entrenched when a shy person has:

The habit of engaging in negative post-mortems. Shy people often engage in negative post-mortems of social encounters that reinforce their faulty, negative beliefs about socializing.

They’ll analyze a conversation they had earlier in the day, but just focus on what they thought went wrong. They’ll keep replaying the moments where they feel they acted awkwardly. The problem with these ruminations however, is that shy people likely don’t have enough information to accurately assess how things really went down.

Researchers have found that because shy people are so self-conscious during a social engagement, they remember fewer details of the event than others who were more comfortable. Shy people are so focused on their inner thoughts and feelings that they’re not really paying attention to what’s going on around them. Because they lack details of what actually happened, they will then fill in the gaps of their memory with “facts” based on the negative feelings they experienced during the social encounter.

Yet just because you felt embarrassed about something, doesn’t mean you actually did or said anything that caused someone to think less of you. It’s easy to mistake your own feelings – which seem all-consuming and incontrovertible because they’re inside your own brain! – with what objectively happened outside yourself.

Negative post-mortem ruminating simply reinforces negative beliefs about socializing, which triggers anxiety about engaging with others, which causes the person to either avoid socializing or, if they do socialize, to be extremely self-conscious about it, which makes them afterwards feel quite embarrassed and glum about how the encounter went…and on the cycle of shyness goes.

Pulling It All Together: The Vicious Cycle of Shyness

Putting the above together, shyness can often be a vicious cycle that looks something like this:

Understanding this cycle is the key that unlocks the power to overcoming shyness. You simply have to work at disrupting the cycle by targeting a specific point or points in it. The points in the cycle that will provide the most bang for your buck are working on becoming less self-conscious and reducing avoidance behaviors, but you should also work on changing other aspects like putting an end to engaging in faulty beliefs and negative post-mortems.

I know. It’s easier said than done, but it is possible. In next week’s post, we’ll show you how.

Read the Entire Series

Part 1: Understand the Nature of Your Shyness

The Complete Guide to Overcoming Your Shyness

___________

Sources: