After WWII and before the Korean War, America experienced a short period free from the fear of war and conflict. People were optimistic about a future of peace and plenty. My guest today calls this time the “era of bright expectations,” and he experienced it firsthand as a young man who had just graduated from college. The era’s burgeoning sense of optimism inspired him and a few of his college buddies to set out on a road trip up to the Canadian wilds in search of the spirit of romance and adventure.

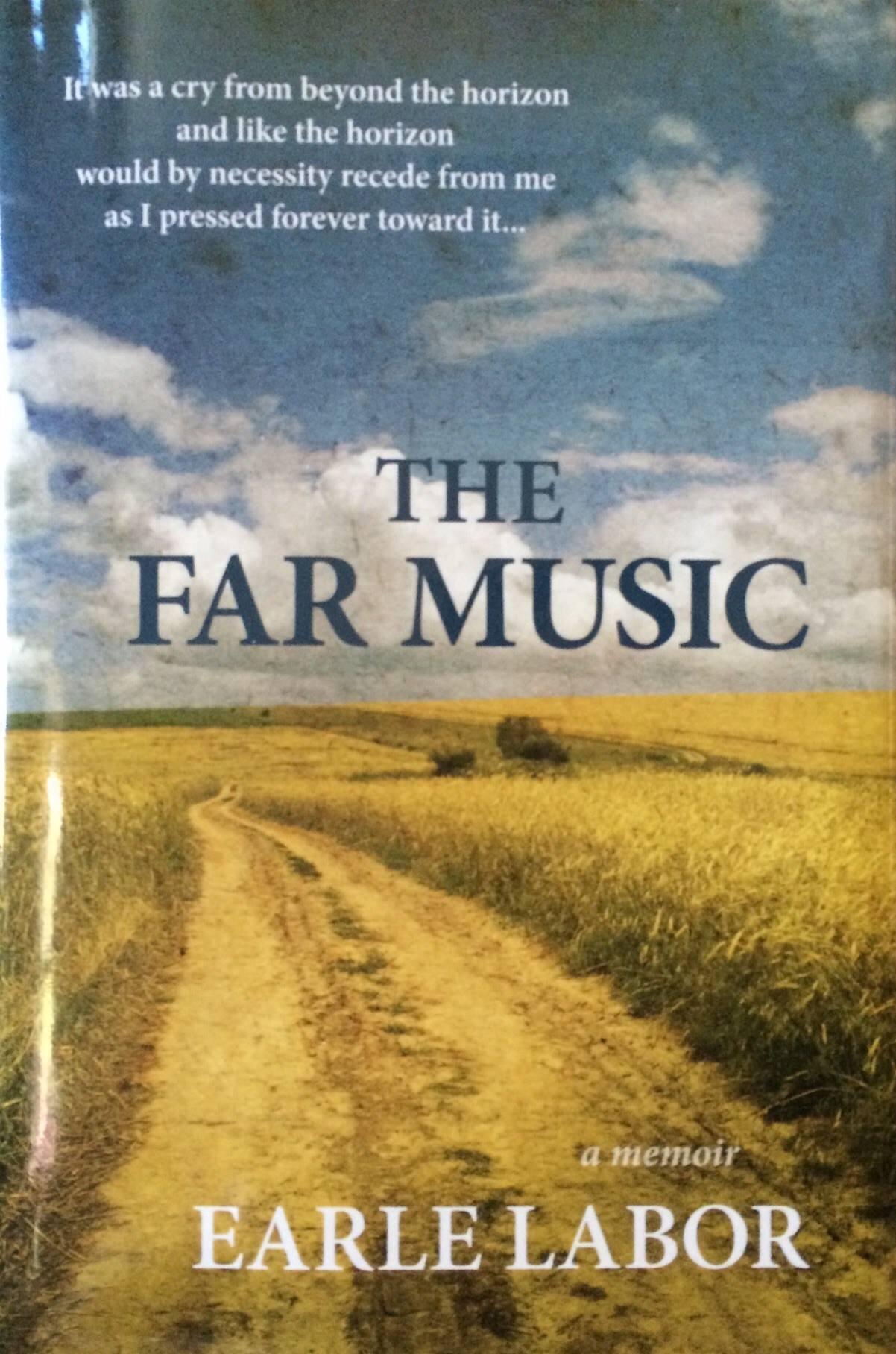

My guest’s name is Earle Labor, and I’ve had him on the show before to discuss his landmark biography on Jack London. Today, we talk about his memoir of this youthful trip of his: The Far Music. Earle tells us what life was like right after WWII and before the Korean War, and whether he regrets just missing the chance to fight in WWII.

We then discuss Earle’s right of passage road trip from Texas to Canada. He talks about hitchhiking, sleeping in barns, fields, and state fair grounds when he and his buddies didn’t have money, and how they ate during those lean times. Earle then talks about the jobs they worked along the way to save money for their stay in Canada, including farming, building grain elevators, and bagging alfalfa for an entire week with little or no sleep. Earle even did some time prize fighting and worked at a burlesque theater.

We end our conversation talking about the outcome of that trip, and Earle makes an impassioned call to men to celebrate their manliness and to never lose the spirit of romance and adventure. You don’t want to miss it.

Show Highlights

- Why Earle calls the years between WWII and the Korean War “the era of bright expectations”

- Does Labor feel like he missed out on serving his country in WWII

- What was college like in those interwar years?

- The difference between students today and students in the 1940s

- What does “the far music” mean?

- What inspired the adventure to Canada?

- How Earle and his buddy (Pink) traversed across America without a car

- Earle’s experience working the alfalfa mill

- Their brief time working at a burlesque theater

- Earle’s prize-fighting career

- Why Earle doesn’t consider the trip a failure even though they didn’t make it to Canada

- How Labor’s road trip differed from Jack Kerouac’s (which happened at the same time)

- How this trip influenced Labor’s life

- Can young people take the same sort of trip today?

- Labor’s advice to young folks today

Resources/People/Articles Mentioned in Podcast

- My first podcast with Earle Labor about the life of Jack London

- Jack London: A Life by Earle Labor

- Why Every Man Should Study Classical Culture

- Travel Like Your Grandfather: Hitchhike Across the States

- Champion (Kirk Douglas film)

- On the Road by Jack Kerouac

- Martin Eden by Jack London

- Never Give Up Your Sense of Adventure

Note: The Far Music was printed in a limited run by SMU Press. It currently cannot be found of any of the major online book dealers; keep an eye out though, maybe give your local used book proprietor a heads up that you’d like it, and maybe you’ll get lucky!

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Podcast Sponsors

The Art of Manliness Store. Check out our newest items, as well as our clearance on grooming products, and take an additional 10% off by using “AOMPODCAST” at checkout.

ButcherBox delivers healthy 100% grass-fed and grass-finished beef, free-range organic chicken, and heritage breed pork directly to your door. For FREE Bacon and $20 off your first box, go to ButcherBox.com/manliness and enter MANLINESS at checkout.

The Great Courses Plus. At the start of the year, we all think about ways to better ourselves and learn new things. I’m doing that by watching and listening to The Great Courses Plus. Get a free trial, or sign up for the Annual Plan and get $20 off! Visit thegreatcoursesplus.com/manliness.

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Recorded with ClearCast.io.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Welcome to another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. After World War II and before the Korean War, America experienced a short period free from the fear of war and conflict. People at this time were optimistic about a future of peace and plenty. My guest today calls this time the era of bright expectations, and he experienced it firsthand as a young man who had just graduated from college. The era’s burgeoning sense of optimism inspired him and a few of his college buddies to set out, all the way from Texas, on a road trip to the Canadian wilds in search of the spirit of romance and adventure.

My guest’s name is Earle Labor, and I’ve had him on this show before to discuss his landmark biography on Jack London. Today we talk about his memoir of this youthful trip, it is called The Far Music. Earle tells what life was like right after World War II and before the Korean War, and whether he regrets missing the chance to fight in World War II. We then discuss Earle’s rite of passage road trip from Texas to Canada, he talks about hitchhiking back in those days, sleeping in barns, fields, and state fairgrounds when he and his buddies didn’t have any money for a room at the YMCA, and how they ate during those lean times. Earle then talks about the jobs they worked along the way to save money for their trip to Canada, including farming, building grain elevators, and bagging alfalfa for an entire week with little or no sleep. Earle even did some prize fighting for a bit to make some money, and also worked at a burlesque theater in Kansas City. We’ll talk all about that.

We then discuss what the difference was between his road trip and Jack Kerouac’s road trip, which was going on at exactly the time. That road trip inspired On the Road. We end our conversation talking about the outcome of his trip, and then Earle makes an impassioned call for men to celebrate their manliness and to never lose the spirit of romance and adventure, even as they get older. You don’t want to miss this show. As you listen, you’ll probably notice that I’m speaking a little bit slower, articulating my questions a bit more. Earle is almost 90 years young, so he’s a bit hard of hearing, so I had to make sure he could understand me. Earle joins me now by phone.

Earle Labor, welcome back to the show.

Earle Labor: Thank you very much. It’s great to be here, Brett.

Brett McKay: So you have a new memoir out and it’s about a specific period in your life and history. It’s the years 1945 through 1950, and you call this period the era of bright expectations. Why is that?

Earle Labor: I’ll tell you, Brett, it’s an amazing phenomenon in that this particular era between the end of the Second World War and the beginning of the Korean War was absolutely distinct, unique, but it’s been neglected. Unlike the ’20s and what have you, there was a terrific kind of optimism. I called it a bubble of euphoria during this period, because we’d just gone through the worst depression in American history, and gone through the most horrendous war in world history. We’d won that war and emerged as the most powerful nation in the world. We were ready to meet any kind of challenge, and there was a kind of optimism there that was never there before and, I’m afraid, hasn’t been there since. I wanted, in the book, for readers to understand the distinction, or the wonderful uniqueness of that particular five years.

Brett McKay: You were too young to fight in World War II, did you ever feel like you missed out on taking part in it?

Earle Labor: Yes and no. When the war began, like most other young guys at the time, I was chomping at the bit to get in. I wanted to be a fighter pilot. If I’d have been a year older, I might … as I say in the book, I might not be here to talk now, or might not have been able to write the book, because I might be dead.

As the war went on, especially later, I think my enthusiasm waned a bit. For example, one of my best friends, was just, I guess, less than a year older, and he went into the army in the late summer or early fall of 1944, and hadn’t been in there six months when he was killed in the Battle of the Bulge. So I’m just saying that I sort of have mixed feelings about getting in there to the fight.

Brett McKay: So you attended SMU during this time. What was SMU like after World War II?

Earle Labor: Well, it was no longer … at least for a few years, it was no longer the country club of the South, which it had been, and I don’t know if we have that reputation now. I think it’s got a terrific reputation and I’m proud of my Alma Mater, but during that period, with all the veterans coming back on the GI Bill, the atmosphere was quite different from now.

I’ve got to say that our culture, of course, was very different then, than it is now. There was more of a sense of unity and a sense, as I said earlier, of optimism. Our professors, so far as I had any idea, were not politicized. I never got a sense that they were a member of one particular party or another, and the students, I think, were not as politicized as they are today. In fact, most of us, especially the veterans I’d say, were more interested in learning how to improve their lives through college education. I don’t remember anybody wanting to protest at the time, and it was just, I’ve got to say, I considered a more wholesome situation, maybe even saner then, than I notice out there today.

Brett McKay: You’re a college professor, that’s what you did. Do you notice a big difference between students today, besides the wanting to protest, the politicization? Is there a difference between students today and the ones you saw in the 1940s?

Earle Labor: I’ve noticed a number of differences, Brett, in terms of the attitude and, as I say, there was not the kind of disunity we see, not the kind of protesting, taking political sides or what have you. Even the curriculum was very different back in those days. We were still studying the classics like Shakespeare and even the Roman and Greek classics, what have you, instead of trying to … being more politically correct or whatever. I think the students back then, once again, were more, in one sense I guess, patriotic, maybe even more conservative or what have you, less inclined to raise hell than they became later on.

Brett McKay: Your memoir is called The Far Music. What’s that reference to?

Earle Labor: Let me take a little time for this one, Brett. The idea of escaping, of going back to nature, hitting the road and what have you, getting away from all the pressures of society, that essentially was my idea. Wanting to get up to the Canadian wilderness, work our way up on the road to get to the Canadian wilderness, go out there and build a cabin and spend a year away from society and all the pressures that are put on you by society.

The title of the book, though, the idea of writing a book about it, was my buddy Pink Lindsey’s. He was a World War II veteran. He was only a couple of years older than I, but he seemed much older because of what he had been through in the war. He was like a big brother, almost like a father figure to me, and he was physically the strongest man I’d ever met at the time, and we bonded. Both of us were weightlifters and that’s where I first met him, up at the gym at SMU, working out with the weights. We bonded almost immediately, he’s just a good old boy from … P.B. Lindsey from Gilmer, Texas, and my home was Pittsburgh, Texas, at the time, about 20 miles from there.

Anyhow, back to Pink, he’d come to SMU on the GI Bill, to be a pre-med and become a doctor, but he took a course under a professor, George Bond, on the American novel, and read Jack London’s Martin Eden. As a result of that, he decided he wanted to become an English major and become a professional writer. What he did before he died, he wrote several pages of a manuscript called The Far Music. That was his term, and I got to credit him with the idea of the book. He was essentially a poet, I think.

I’m reading and giving you a shortened version of some of this, that he left behind, in a manuscript that he left for me. He said, about the far music, “It is the music of the spirit and the heart and the soul that lies deep within us. The sleeping beauty that dwells below the surface of mean experience. Perhaps it can only be heard when we are very young, because I was then young and had known no great and abiding sorrow, in spite of the indescribable and unthinkable things I’d witnessed in war. I felt optimistic about my search, for the days of my life were new, and the machine which was my body was new, and sinew and blood and bone worked together in that admirable way, so peculiar to early years. It is a cry from beyond the horizon and, like the horizon, would, by necessity, recede from me as I pressed forever toward it.” I love that section from his manuscript. As I say, that’s the best description I can think of, what we meant by the far music.

Brett McKay: I love that. You said you had this idea to go to Canada. Was there something that inspired that adventure, or was there someone, an author? What was the inspiration behind the adventure?

Earle Labor: Well, I think both of us were tired of book work by the time we graduated, in 1949. We’d been pretty steady at the books for four years there, and wanted to get away from not only the books but also the other pressures of society. In fact, both of us had some fairly passionate love affairs. In my case, I’d gone with this lovely young woman for three years and everybody expected us to get married, and so did I, but as we got closer to the date of graduation I began to think, look, I’m not ready for the responsibilities that come with marriage and family. Pink, on the other hand, had had a pretty passionate affair with a young woman who was older than most of the SMU students, and that had kind of burned itself out. I think both of us were ready to hit the road and have a different kind of romance, if you accept that term.

Brett McKay: What was the original idea of your adventure? Was it … ? It was to get to Canada, but you had to work your way up there.

Earle Labor: That’s right.

Brett McKay: So what was the plan?

Earle Labor: We thought, originally, we might follow the wheat harvest up there but the wheat harvest was delayed by a couple of weeks by rain that summer, so we started working in grain elevators throughout Kansas and that was the main source of our income for most of the summer, until we settled down in Kansas City later on, round the 1st of September or so. We worked on … let’s see … building grain elevators in Meade, Kansas, and Wichita, and finally in Hutchinson, which was supposed to be the largest grain elevator ever built, up there.

Brett McKay: And what was that work like? Was it back-breaking labor?

Earle Labor: Well, it was warm. It was hot out there, and I can remember the first day out, working at Meade, we hadn’t prepared much in the way of sandwiches. I think peanut sandwich and maybe that was about … peanut butter and jelly, and our job was digging a ditch out there. We had … The elevator, there in Meade, was almost finished and we had to dig a ditch for the electrical connections, up to the main … the head house as they called it, the main part of the elevator.

And I can remember, ordinarily, you know, a young man will fantasize about sports and maybe about girls and what have you, but I remember I had a different kind of fantasy that day because I was so hungry and hot out there. My Uncle Glen had been taking me, once a week when I was in college, to this cafeteria close to campus, in Dallas, and so all day long, out digging that ditch, I was going through the line in my fantasy, getting all these salads and other desserts and what have you, all day long while I was digging the ditch.

Pink had a different story about it, he described the shovel in different terms. He said, “I believe that in the final tally, a reckoning would be that with the slow and subtle attrition of time, the pen shall be mightier than the sword, but of one thing I’m fairly certain, the shovel is mightier than both.” He talks about being out there, so hot, and working on this ditch, “I don’t see how God ever created the universe out of nothing, for we, as his creatures, are not capable of building anything without first digging a ditch.”

He says, “A draft of wind that suddenly sprang up at mid-morning across the Kansas Plains was cool, surprisingly enough, and was our salvation. I thought of all things significant, the clashing of worlds and the far space, the haunting melodies of Tannhauser, the magnificence of Beethoven’s Ninth, the bursting seeds of life, the cold inexorableness of death, the ever-moving globe, time and space, and somehow failed to reckon that what manipulation of all things natural and unnatural, I’ve been coerced into being at this spot at this time. I’m sure there must be some great moral attached to all of this, but as my breakfast played out about 11:00, I felt an even deeper ache that there was some great moral to all this, but I’ll be a son of a bitch if I know what it is.” I had to share that with you, whether or not you got time for it or not but, anyhow, let’s move it along here as best we can.

Brett McKay: So how did you travel from job to job? You didn’t have a car, that first part of your trip, correct?

Earle Labor: At first, we were hitchhiking, which was no big problem back in those days. I wouldn’t advise it today because of all the craziness out there but we, for the first several weeks, we were on the road hitchhiking, then we got enough money to come back to Texas and get a used car. We bought … Pink’s uncle, Hiram Lindsey, owned a used car dealership in Gilmer, Texas, and he took us down to Longview for a dealer’s auction. We bought a little 1940 Ford for $400, and that was our transportation, almost to the very end there.

Brett McKay: And where did you sleep? What did you do for lodging?

Earle Labor: Let’s see … The most common way of sleeping was in the car, either the front … we’d switch back and forth between the front seat and the back seat. The back seat was more comfortable. It was a sedan, as I should have pointed out. Anyhow, as we were on the road, if we spotted a haystack, I preferred that. Pink, having grown up on a farm, knew about snakes in haystacks, but I wasn’t that worried about it and if there was a snake in one of the haystacks I slept in, we didn’t bother each other.

There was a period when we working at the grain elevator in Hutchinson, Kansas, before both of us could get a room at the Y. Pink managed to get in but they were short of rooms, and for a week out there, I slept outside town in the woods. There was one memorable experience, I’ll share it with you. We worked from 7:00 at night to 7:00 in the morning on that grain elevator. We’d come back in and I’d get some breakfast and I’d walk on out, or trot on out, to the edge of town, out to the woods, and find a place that was comfortable, under the trees out there. I’d sleep from about 9:00 in the morning to about 3:00 in the afternoon, something of that sort. One afternoon, I was asleep and I heard this voice in the distance and I couldn’t figure out what it was. As it came near, some kid was yelling, “Hey, Charlie. Hey, Charlie. Come over here. I see a dead man over here.” I thought, well, I better let those kids know that I’m alive. I raised up … and they were about, what, 50 yards away or so, I’m guessing about 10 years old, out exploring the woods. I raised up and as I did that the one in lead says, “Oh, don’t bother. He ain’t dead, after all.” He was disappointed that the corpse had some life in it.

Anyhow, I guess that’s enough about sleeping. There was one time we slept in oat fields out in South Dakota but, mainly, it was the car.

Brett McKay: Besides the grain elevators, you spent some time working at an alfalfa mill and can you tell us a little bit about that?

Earle Labor: The alfalfa mill … I think … I’m going to … Hold on just a minute. I think that was … I’m going to paraphrase Charles Dickens here; it was the best of jobs, it was the worst of jobs, Brett. I mean, the best and it was the worst. It certainly is the most memorable. The worst, meaning it was the unhealthiest. I point out in the book that it was unhealthier than working in the heat, stringing barbed wire fences in East Texas and bailing hay, plowing wheat fields in Oklahoma, or trimming hams for Armour’s meat packing plant in Kansas City. Even, hell, it was unhealthier, I think, if less dangerous, than what I’d done working on a maintenance crew for Lone Star Steel Company, not to mention the work we’d done on the grain elevators. But it something very special.

I’ve got to point out, these alfalfa mills are not the same today as they were back 70 years ago. This one out, about seven miles west of Larned, Kansas, was a mill where they bring in the cut alfalfa. They bring in the harvested alfalfa in trucks from the fields, and they dump it in the top of this building they’ve got there, this structure, where it’s chopped up and dried, and it comes down through pipes, down to the floor, that are bifurcated. And here’s what we encountered; on the floor that we worked, down at the bottom, each of these three major funnels or pipes, where they chopped and dried alfalfa, which was intended for stock feed, by the way, each was bifurcated, and there were a lot of gunny sacks.

You put a gunny sack on, one of those on one opening there, and you fill up that gunny sack to approximately 100 pounds, and then you flip over the lever to another gunny sack while you take this one that’s full. You take it off, take it over to scales, weigh it up to exactly 100 pounds. There’s a shovel there and there’s a barrel that you can either get a little more out of or put some in to make sure you’ve got exactly 100 pounds in each of those gunny sacks. You sew up the gunny sack, you put it on a dolly until you get three or four stacked there, then you take the dolly out to the deck outside. There’s a boxcar out there and you stack those gunny sacks up to the top of the boxcar there.

Now, that’s pretty strenuous work. Both of us were champion weightlifters so that wasn’t much of a job, it wasn’t too much, but what was really the toughest was the air. It was filled with this green dust and the dust got into your eyes and your ears and your nose and your lungs, and I don’t know why in the world they didn’t provide some kind of mask for us but they didn’t. And there’s supposed to be six men working at that, eight hours, around the clock, on three shifts, and they couldn’t keep them there. Guys either quit because of the work or they quit because they got sick.

Pink and I finally, toward the end of that, I think it was about three weeks there, they had only the two of us working around the clock. And we tried to split up the time so that we’d be just one man doing that and the other one would try to get a little rest and food. But that was the most horrendous job that we had, and I’d say the healthiest. As a matter of fact, Pink, who was so strong, actually got some kind of dust pneumonia or whatever that he had, took him months later to shake.

But that was, as I say, the most memorable experience we had, there in the alfalfa mill. Nowadays they don’t have that. We went back 37 years later, to that site, and the mill had been torn down. We noticed that several miles from there, there was another mill but they make the tablets … they make the alfalfa feed now into tablets without all that dust in the air.

Brett McKay: Yeah, so you and Pink end up in Kansas City. What did you do for work, there?

Earle Labor: Kansas City, we had originally, by the time we finished our work at the alfalfa mill, we saw it was too late to go up to Canada and build a cabin out in the wilderness, that the snows would set in before we could really get all that done. So we decided we’d go back to … we’d go to Kansas City and see if we could get some jobs there until the next spring when the weather warmed up, then we’d go on back to do our odyssey, and go on up to Canda.

Pink had … he’d been a farm boy and he’d gone into the army when he was 17. He’d never really had a job in the city, so he had some problems getting a job in Kansas City. I was okay. I was lucky in that, during the war, I had worked the boy scout counter at Titche-Goettinger, this big department store in Dallas. So I managed to get a job at Peck’s department store in Kansas City, selling luggage and men’s accessories, which was okay except that I didn’t get but about $20 a week after taxes, and after we’d been there a couple or more weeks, Pink hadn’t been able to get a job. I said, “Look, buddy, we can’t get by on what I’m making here and not pay the rent here at the YMCA and also feed ourselves.”

So we looked at the Sunday edition of the Kansas City Star and we saw an ad in there that said, “Salesmen wanted, working conditions very good and pay is fine,” et cetera, et cetera, and put the address of the place for us to apply. It turned out that the address was the same address as the famous Folly Theater in Kansas City, which has now been restored, by the way, as a historic landmark. I mean, it’d been a site for famous comedians, like the Marx Brothers, Bob Hope, Jack Johnson and Jack Dempsey had put on exhibitions there. Frank James, the brother of Jesse, had been a ticket collector or something at the Folly Theater in its history.

Now, by the time we went there, it was on the skids. It was just a burlesque theater. Wasn’t nearly as fancy as it had been back in the ’20s and ’30s. But we interviewed for the job and the man said, “Well, you’re going to be selling some stuff during intermissions here, between the burlesque acts and what have you. You’ve got cold drinks to sell for 15 cents, and you sell some candy that we’ve got here for 25 cents a box, and you also can sell this literature that we distribute for 25 cents a copy.”

Well, the literature, as you can imagine, was not the kind that you usually got on the newsstand back in those days. It was, I think, pretty tame compared to what’s out there now, very openly, but back then it was kind of forbidden stuff. I can remember the salesmen, we’d go up and down the aisles selling this stuff between the shows, and we would alternate on who sold the cold drinks and who sold the candy and who sold the magazine, and so I developed a spiel when I was … was my turn to sell the magazines, and I said, “Ladies and gentlemen, when you get this little magazine, you let your conscience be your guide.” And then I’d say in a lower voice, “If you don’t have a conscience, you won’t need a guide.” And I got down to the front and I turned around and looked up, Pink was selling cold drinks up in the balcony. He was bent over the rails, laughing.

When we went up to the room we stayed in between shows and what have you I said, “What the hell were you laughing at?” He says, “I was wondering what SMU president, Umphrey Lee, would have thought, if he came in here and saw his outstanding man selling that kind of stuff.” I said, “Pink, I don’t think either of us would have said anything at the time. I think we’d have kept it quiet.”

Anyhow, I got to tell you this, Brett, we encountered virtually no meanness this whole time, and even in the burlesque show, the stuff that was on stage, the strippers and what have you, was much tamer than what is open to public on TV and everything else out there today. The man who hired us … when Pink was he never did quite recover from that dust that he’d got at the alfalfa mill and decided to go back to Texas and get well down there, and then he’d come back to Kansas City and we’d resume our trip. When he got ready to go back and told Al, the manager, that he had to quit, Al himself reached into his pocket and pulled out a $10 bill and gave it to him. Of course, $10 meant more back in those days than now, but I’m just saying that throughout this adventure, we encountered people who were really decent and caring.

Anyhow, so that was Kansas City. Now, I lucked out later on. After Pink left, I think I’ve told you, I said something in the book about my brief career in the ring. May we talk a little bit about that?

Brett McKay: Yeah, talk about your prize fighting career.

Earle Labor: I’d been working for Peck’s department store, only getting about $20 a month, but I managed to save up enough, finally, there was a lovely young woman working ladies lingerie there, at Peck’s, and so I saved up enough to take her out on a date. We went to see the … After having Cokes and what have you at the drugstore when we got off work, we went to see the movie Champion, which just come out. Champion with Kirk Douglas. It’s a great movie. I think it’s probably the best movie he ever made.

Anyhow, if you don’t know much about it, he’s a boxer there who becomes world champion, et cetera, et cetera. I won’t go into the plot for you, but a terrific movie, and we’re coming out of the movie and my date, named Mary, she said, “You know, Earle, you look kind of like Kirk Douglas.” So, you know, as my Mom used to tell me, I was full of it back in those days, full of myself. And I decide, well, shoot, maybe I can do a little boxing myself.

They had a boxing team at the Y and I trained up there. Finally, my coach said, “You know, you might like me to enter you in one of the bouts next Tuesday.” Now, back in those days, I don’t know how it is now, but in those days, Kansas City was big on amateur boxing. Every Tuesday night in the Coliseum, the main auditorium downtown, they’d have these amateur fights, about half a dozen of them, amateurs. Now, I’ve got to tell you, they weren’t strictly amateurs, because under the cover they paid you ten bucks to fight up there. So I could claim a brief career as a semi-pro, if I wanted to.

The first fight, I was matched up against a young fellow that had very little more experience than I did and I won the fight and, boy, I was so proud of myself. So Jules Schneider, the coach, says, “Earle, you’ve got a natural straight left,” he say, “You’re going to do well. I’m going to put you in the ring with Billy, here.” Billy was a kid who’d had about 27, 28 fights. Well, I thought, you know, he’s a fancy Dan but I might get lucky and win this fight, too. Turned out that I didn’t get lucky and he beat the hell out of me.

I was a mess when I … I didn’t realize it at the time because my adrenaline was flowing, but when I got down afterwards, looked at myself in the mirror, I was shocked. I mean, my right eye, he’d done me in the right eye and it was swollen shut. My right ear was swelling and blue. The whole side of my right face was turning blue, and I’d chipped a tooth and what have you. Wasn’t wearing a mouthpiece back then because I thought it was strictly for fun. It occurred to me, you know, this is not fun at all. These guys are out to hurt me. I’d better stick to weightlifting.

But I couldn’t get … By the way, I didn’t mention that I’d quit my job at Peck’s just the day before because I’d gone in and asked the woman for a raise and she said, “Well, you’re not ready for it yet.” Again, I was … that hit my ego, so I said, “Well, you can have the job.” I figured I could get another job, easy enough. But looking the way I did after that fight, it wasn’t easy. I went around to several places and I explained I was a member of the YMCA boxing team and they would say, “Well, you know, that’s a great sport and we respect that and we’ll call you when we have an opening.” After about a week of that, I realized they weren’t going to call at all.

I lucked out, Brett, when I saw this ad in the Kansas City Star, Armour’s meatpacking plant, across the river over there, was looking for somebody, looking for help. And by golly, they didn’t care how I looked. They hired me to work on the ham line, trimming hams there. It was a lifesaver for me, otherwise I’m not sure how I’d have got by much longer without a job up there.

So that was my brief career as a prize fighter and I’ve never regretted it. Believe me, we know now how much damage the blows to the head do, and I’ll tell you this; for a week after that second fight, my head ached, so I knew that that wasn’t the best thing in the world for me.

Brett McKay: So you didn’t make it to Canada. Did you think the trip was a failure?

Earle Labor: I never … I hope I mention this correctly. Let me tell you that, although we didn’t make it, this was … I call this … Let me put it this way; I call this a happy failure. The two of us had no idea about what those dark frozen months of winter would be like up in the Canadian wilderness. The good Lord was with us, in not letting us get up there. I’m not sure what would have happened.

Even so, I say it was a happy failure because it was really a life changing adventure for me. It not only provided me with a true glimpse of American decency and wholesomeness, but it also proved to me that I could get by on my own without necessarily having to depend on family and friends. That’s when I was up there in Kansas City by myself, after Pink had gone back to East Texas. It was a wonderful adventure, and I’ll talk a little bit more about it maybe when we wrap this thing up, if you like.

Brett McKay: Sure. Your road trip adventure went on about the same time Jack Kerouac was going on his, that inspired On the Road. How would you say your road trip was different from Kerouac’s?

Earle Labor: That’s a great question, Brett. It hits right to the heart of things because Kerouac was on the road at virtually the same time that Pink and I were on the road, but his vision of America in his book, his famous book, was very, very different from ours. I don’t know if you want to call it more cynical or whatever, but … It’s interesting to me, one of the reasons I wanted to publish The Far Music, Pink’s manuscript and what I’d done with it, was to show that there was a different side to America back in the late ’40s than the one that Jack Kerouac presents.

His book … I mean, it’s a great book. I don’t want to denigrate it in any way, but it was more relevant to the ’60s and the beat generation, than to mine. I mean, the kind of stuff that he encountered, we did not find at all. For one thing, he was in a different part of the country most of the time, going from east to California. I think he missed the true heart of America, in states like Oklahoma, and East and West Texas, Kansas and South Dakota. He missed, by and large, the kind of people we encountered.

I think this is worth pointing out; not once, in all those adventures that we had … and we were in some tough places, not once did we encounter drugs. Now, that’s also a different in time. We went back to retrace some of the itinerary 37 years later, I got to tell you this, and we went back to the site of the alfalfa mill out west of Larned. Now, they’d torn down the mill itself. We were out there, I was taking pictures, and some guy in a pickup comes rolling across the field, gets out and says, “What are you fellows doing here?” I explained, we explained that we worked there at a particular time, we were just coming back, kind of, you know, refresh our memories and take some photographs. I said, “What’s the problem?” He said, “I thought you were out here making a pick up. This has become a drug drop.” In other words, Brett, out in the middle of the prairies in Western Kansas, during that period of time, note the transformation from what we encountered and what came later on, after the ’60s and what all.

Also, I think, back to Jack Kerouac, all credit due to him, he missed the kind of men that we worked with, so much worked with their hands in the fields and on the farms and what have you. The kind of guys that Emerson calls … that had what Emerson calls simplicity of character. That doesn’t mean simplicity of mind, but these guys had a kind of intelligence and common sense and integrity that is special to men that work close to the earth, I think. As a result, I developed a deep and abiding respect for both the men and the women that make life so much easier for the rest of us, and what have you. Those of us who take so many of our basic necessities, as well as our modern day luxuries, for granted. Anyhow, I think … I hope that answers your question about Jack Kerouac.

Brett McKay: How did this trip influence the rest of your life?

Earle Labor: Well, I called it a life changing experience for me. Of course, the world has changed so much since then. I’ve not been the same since then. I felt that I came of age, in fact, quite literally. I was 21 years old and, as I said a little bit earlier in our discussion here, I found a part of the world that has, I think, made a terrific influence on me. A very different kind of world than the academic world or even the business world or what have you. It just … It’s something … I said at one point that those musical notes from the far music become a part of me forever, since that adventure. I wouldn’t trade it for anything.

Brett McKay: Did it influence your career to become a Jack London scholar?

Earle Labor: Yes and no. I mean, mainly no, I think, Brett, in that I had really got … I hadn’t got really involved in Jack London until I was in the navy later on, and read that same book that influenced Pink Lindsey. He’s the one that told me, read Martin Eden.

I was on a weekend pass from US Naval Training Center in Bainbridge, Maryland. I was up in Manhattan, browsing the newsstand, and saw a paperback edition of Martin Eden. I said, well, I got to check this out. This is something that my buddy, Pink, said I had to read. Of course, at the time he told me that when I was in college, I had other interests, mainly extracurricular. Anyhow, I bought a 25 cent copy of Martin Eden and started reading it on the bus back to the base. I got back to the base and I was so caught up in it, I turned on my flashlight and finished reading it that night in my bunk. That’s what really determined me, if I ever went back to get a doctorate, I was going to do my work on Jack London, and that was the deciding thing.

Maybe in a deeper sense, unconsciously, that trip influenced me because of the fact that London had been such an adventurer. He was what I … and if you give me a … let me plug my biography, he’s what we call a seeker. He was motivated by that deep seeking drive within us that is on there with the drive for food and sex and what have you.

Brett McKay: Do you think it’s possible for young people to go on an adventure like yours, today?

Earle Labor: It’s possible, I think. Maybe, but much more difficult. For example, I wouldn’t want to see my sons, as young guys, out on the road hitchhiking, with all the craziness and the drugs and what have you out there. I mentioned the deal in Larned, the alfalfa field out there and what have you. I think, you know, it’s possible nowadays for young guys to have adventures, and I think that if they can get out there … and I’ve got a grandson, who climbs mountains, for example, out in Colorado. He’s, I think, done some traveling, but most of it’s been in the car.

I think, as I say, it’s possible, it’s just it’s not as easy now. The jobs, for example, that we were able to get out there, I don’t think that they’re as readily as available as they were 70 years ago.

Brett McKay: Do you have any parting words of advice for young men listening to this show, based on your experience with The Far Music?

Earle Labor: Bear with me, I may … This may sound a little bit like a sermon or something, but I may … I don’t want to sound like a bunch of cliches but I talked about that seeking drive that we have. There’re all kinds of adventures, not just physical, but intellectual and spiritual. I don’t think we should ever give up on that kind of seeking and adventure and, of course, after you get married and have a family, you’ve got to kind of modify the kind of adventuring you’re going to do. But it’s still possible, as I say, not only physical but intellectual and … adventures of the mind and spirit, I would say. Even Jack London, toward the end of his career, discovered the works of Carl Jung and told his wife, “I’m standing on the edge of the world so new and wonderful and terrible, I’m almost afraid to look over into it.” So he was still seeking there, towards the end of his life.

If I had to give some advice, and as I say again, bear with me if it sounds too much like a sermon, I’d say, “Look,” to guys out there, “Look, guys, you’re a vital part of the magic chain of humanity. You’re blessed with a unique identity, a special gift, and make the most of this wonderful adventure we call life. I want to emphasize, celebrate your manhood. Resist all the current sociopolitical pressures to deprive you of your unique identity as a man. This is your own special God-given gift and I’m saying celebrate it while you can.”

Brett McKay: Well, Earle, that was fantastic. Thank you so much for your time, it’s been a pleasure.

Earle Labor: It’s been a great experience for me and I appreciate you, Brett.

Brett McKay: My guest today was Earle Labor. He’s the author of the book, The Far Music. It’s available on Amazon.com. Also, check out his biography on Jack London. It’s called Jack London: A Life. Great biography if you’re interested in that guy. Also, check out our show notes at aom.is/farmusic, where you can find links to resources where you can delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. For more manly tips and advice, make sure to check out the Art of Manliness website at artofmanliness.com. If you enjoyed this show, got something out of it, I’d appreciate if you’d give us a review on iTunes or Stitcher, it helps out a lot. As always, thank you for your continued support. Until next time, this is Brett McKay, telling you to stay manly.