Man, life can be a slog sometimes.

Each day, annoying little piddly things arise that aren’t hard to manage one by one, but, when taken together, really muck up your mojo. Your car breaks down, your kid gets sick, an employee loses a file, you’ve discovered a leak in your roof . . . and it’s just 9 a.m.

How do you handle these small-but-rhythm-destroying vexations? How do you deal with slog-inducing annoyances without letting them throw a wrench in the gears of your goals?

Thankfully, famed war strategist Carl von Clausewitz provided some insights in his landmark work, On War, that are just as applicable to the home and office, as the battlefield.

Friction, Friction Everywhere

Everything in war is very simple, but the simplest thing is difficult. The difficulties accumulate and end by producing a kind of friction that is inconceivable unless one has experienced war.

Clausewitz’s most enduring and insightful idea in On War is friction.

Friction explains why a general can have a plan for battle that looks perfect on paper, but falls apart in real life. Friction torpedos morale and slows down action.

Friction isn’t just one thing. It’s the accumulation of a bunch of little things. Says Clausewitz:

Countless minor incidents—the kind you can never really foresee—combine to lower the general level of performance, so that one always falls far short of the intended goal.

To help his readers understand friction in warfare, he gives an analogy from everyday life in the 19th century that we can still imagine parallels to today:

Imagine a traveler who late in the day decides to cover two more stages before nightfall. Only four or five hours more, on a paved highway with relays of horses: it should be an easy trip. But at the next station he finds no fresh horses, or only poor ones; the country grows hilly, the road bad, night falls, and finally after many difficulties he is only too glad to reach a resting place with any kind of primitive accommodation.

As the complexity in any endeavor increases, friction increases as well, because there are simply more opportunities for things to get mucked up. The bigger and more complicated the endeavor, the larger the amount of friction.

A factor that increases complexity, and thus friction, more than any other, is the inclusion of other human beings. Humans are the ultimate friction creators. Clausewitz notes that a battalion, by its very nature, will experience plenty of friction, because it’s made up of many different individuals who can interact with each other in a multiplicity of problem-producing ways. One soldier gets scared and runs, resulting in other soldiers catching the fear contagion and running. Before you know it, you’ve got an unplanned, chaotic retreat. Damn you, friction!

If life seems like an annoying slog sometimes, it’s because of friction.

Any endeavor, whether it’s planning a party or starting a business or just living life, will encounter friction along the way. Little unforeseen pain points come together to make what seems easy to accomplish in theory, pretty hard to accomplish in practice. And because most of what we do in life involves our fellow human beings — the Vesuvian volcanoes of vexation — we experience a lot of friction in our lives.

If you want to avoid the annoyances of friction, just stay in your house, avoid people, take no action, and be an isolated, lifeless blob.

But what kind of life is that?

So if friction can’t be avoided, how do you handle it?

Overcoming Friction Through Romantic Genius

To understand Clausewitz and his theory on war, you have to understand that he was a product of 19th century German Romanticism. This is the same movement that gave birth to the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche and the composer Richard Wagner.

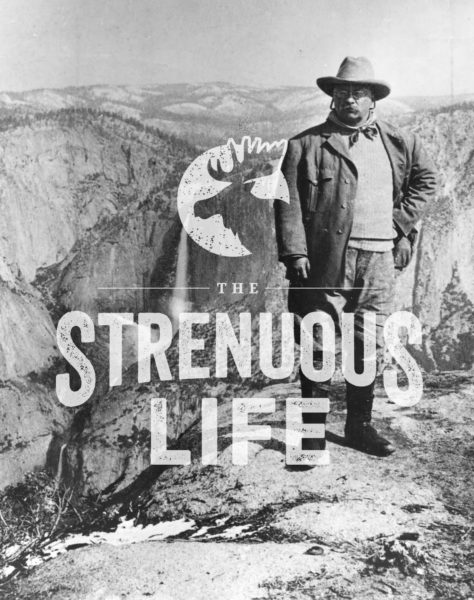

For Clausewitz, all successful generals are geniuses in the Romantic sense. They have a constellation of mental and psychological characteristics that allow them to impose their individual will on the world around them. Romantics see life as an epic struggle between good and evil, action and inertia, mediocrity and greatness. They, as Isaiah Berlin put it, “search after means of expressing an unappeasable yearning for unattainable goals.” These qualities, along with traits like intuition and boldness, marked Clausewitz’s ideal of the Romantic leader. If you want an embodiment of this ideal, just look at Napoleon.

Clausewitz believed that it was through harnessing the elements of the Romantic constitution that a man could deftly grapple with the obstacle of friction.

Change Your Mindset on Friction

Anger and frustration largely arise from a mismatch of expectations. You thought things would go one — wholly smooth — way, but instead run into unforeseen obstacles. In the gap between how you envisioned things would happen and how they actually do; in your grief over the death of the scenario you imagined; in the effort needed to adjust to new circumstances; irritation burbles up.

Thus, Clausewitz says, the first step to getting a handle on friction is to recognize its reality, and inevitability:

An understanding of friction is a large part of that much-admired sense of warfare which a good general is supposed to possess. . . . The good general must know friction in order to overcome it whenever possible, and in order not to expect a standard of achievement in his operations which this very friction makes impossible.

To keep friction from throwing you for a loop, you have to manage your expectations; you have to account for friction in assessing what you’re realistically going to be able to accomplish. Making this assessment, accurately gauging how much friction you’ll encounter, Clausewitz says, is a matter of instinct, honed over time and field-testing:

As with a man of the world instinct becomes almost habit so that he always acts, speaks, and moves appropriately, so only the experienced officer will make the right decision in major and minor matters—at every pulsebeat of war. Practice and experience dictate the answer: ‘this is possible, that is not.’

Even though it’s crucial to accept the inevitability of friction, this needn’t be a matter of resentful resignation. If friction is normal in any endeavor, then it is something to embrace, and even take a kind of pride in — a sign that you’re doing something, taking action, engaging in life’s heroic struggle.

Dominate Friction Through Sheer Psychological Will

Iron will-power can overcome this friction; it pulverizes every obstacle . . . The proud spirit’s firm will dominates the art of war as an obelisk dominates the town square on which all roads converge.

So in any operation, friction is inevitable. How then do you deal with it?

For Clausewitz the Romantic, only the general with heroic strength of will can overcome the quicksand-ian pull of friction. In his chapter on military genius, he describes strength of will as being composed of four elements: energy, staunchness, endurance, and strength of mind.

Energy for Clausewitz is about emotion. He understood that action requires motivation and motivation requires feeling; Stoicism has its limitations. The bigger the action, the more feeling-based animation is needed: “Great strength,” Clausewitz says, “is not easily produced where there is no emotion.” Clausewitz believed that ambition or the desire to be the best was the most powerful energy-giving emotion in war.

Staunchness is the ability to not get rattled by a single setback or failure.

Endurance is the ability to face a whole series of setbacks without wavering.

Strength of mind is “the ability to keep one’s head at times of exceptional stress and violent emotion.” For Clausewitz, a heroic genius needed strong emotions, but these feelings couldn’t be allowed to run to extremes; emotions had to be checked and channeled through self-control.

The combination of these attributes gives a man the strength of will to power through friction. And it is only by powering through friction, that he gains this strength of will.

Eliminate Friction Where You Can

Even though Clausewitz instructed would-be commanders to overcome friction via iron willpower, he notes that “of course [this effort] wears down the machine as well.” Willpower is a limited resource; the more you use for one thing, the less you have for others.

So while some friction is inevitable in any endeavor, you should eliminate it where you can: Not in giving up a goal in order to avoid its attendant friction, but in instances where it serves no purpose — where it arises due to inadequate planning, or merely acts as a superfluous, progress-impeding annoyance.

Some friction can be eliminated through redundancies. In war, Clausewitz said, a battalion could have a strategic reserve of food and arms, ready to be tapped if/when a breakdown in logistics occurred. You can bring an extra pen to a meeting in case yours runs out of ink; have a contingency plan for your Saturday in case the park you want to hit isn’t open; know how to use a paper map in case your phone can’t get a signal.

Automation can eliminate some friction too, especially concerning “life admin” tasks like managing your finances, and even your social life.

Save yourself steps where you can. Simplify every aspect of your life. Declutter your digital devices, and your house. Practice mise-en-place in your kitchen, and your home office.

To sum up, here is Clausewitz’s battle plan for overcoming the friction that threatens to turn life into an annoying slog:

- Embrace life as a Romantic struggle for greatness.

- Recognize friction as normal; don’t lose your head over an inevitability.

- Surmount friction through strength of will.

- Eliminate friction where you can.

- Enjoy the fruits of victory!