Welcome back to our series on Classical Rhetoric. Today we’re continuing our five-part segment on the Five Canons of Rhetoric. So far we’ve covered the canons of invention, arrangement, and style. Today we’ll be covering the canon of memory.

The Three Elements of the Canon of Memory

1. Memorizing one’s speech.

Anciently, almost all rhetorical communication was done orally in the public forum. Ancient orators had to memorize their speeches and be able to give them without notes or crib sheets. Note taking as a way to remember things was often looked down upon in many ancient cultures. In his Phaedrus, Plato has Socrates announcing that reliance on writing weakened memory:

If men learn this, [the art of writing] it will implant forgetfulness in their souls: they will cease to exercise memory because they rely on that which is written, calling things to remembrance no longer from within themselves.

So if you were an ancient Greek and busted out some speech notes in the Assembly, you’d probably be laughed at and mocked as weak-minded. The canon of memory then was in many ways a tool to increase an orator’s ethos, or authority with his audience.

In modern times, we still lend more credence to speakers who give their speeches (or at least appear to) from memory. You just need to look at the guff President Obama caught a few years ago when it was revealed that he almost never speaks without the help of a teleprompter. He relies on it whether giving a long speech or a short one, at a campaign event or a rodeo. And when the teleprompter malfunctions, he often flounders. This reliance on an oratorical safety net potentially hurts Obama’s ethos in two ways. First, whether fairly or not, when people know that a speaker needs a “crutch” for their speeches, it weakens their credibility and the confidence the audience has in the speaker’s authenticity. And second, notes put distance between the speaker and the audience. As a television crewman who also covered Clinton and Bush put it in reference to Obama’s use of the teleprompter: “He uses them to death. The problem is, he never looks at you. He’s looking left, right, left, right — not at the camera. It’s almost like he’s not making eye contact with the American people.”

This truth isn’t just limited to the POTUS. Think back to the speakers you’ve heard personally. Which ones seemed more dynamic and engaging? The man with his nose buried in his notes, reading them verbatim from behind the lectern…or the one who seemed like he was giving his speech from the heart and who engaged the audience visually with eye contact and natural body language? I’m pretty sure it was the second type of speaker. It pays to memorize your speech.

2. Making one’s speech memorable.

For ancient orators, the rhetorical canon of memory wasn’t just about the importance of giving speeches extemporaneously. The second element of this canon entailed organizing your oration and using certain figures of speech to help your audience remember what you said. What good is spending hours memorizing a persuasive speech if your listeners forget what you said as soon as they walk out the door?

3. Keeping a treasury of rhetorical fodder.

A third facet of the canon of memory involved storing up quotations, facts, and anecdotes that could be used at any time for future speeches or even an impromptu speech. A master orator always has a treasury of rhetorical fodder in his mind and close at hand. Roman rhetoricians like Cicero and Quintilian didn’t subscribe to the Greek prejudice against note taking and encouraged their students to carry small journals to collect quotes and ideas for future speeches. Renaissance rhetoricians continued and expanded on this tradition with their use of the “commonplace book.”

Below we’ll take a look at some of the methods classical rhetoricians used to implement the three different aspects of the canon of memory in more detail.

Memorizing Long Speeches

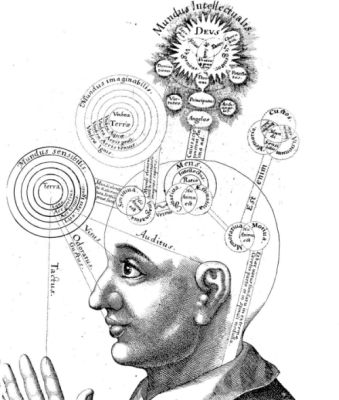

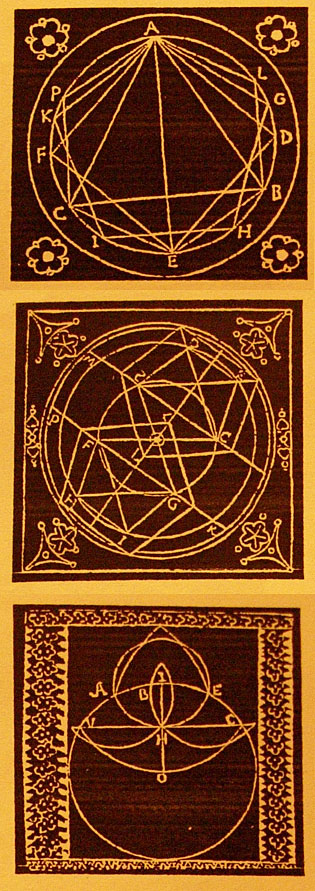

Renaissance memory seals to implement the method of loci technique.

Because the orations of ancient rhetoricians could last several hours, they had to develop mnemonic devices (techniques that aid memory) to help them remember all the parts of their speeches. The most famous and popular of these mnemonic devices was the “method of loci” technique.

The method of loci memory technique was first described in written form in a Roman treatise on rhetoric called ad Herennium, but it also made appearances in treatises by Cicero and Quintilian. It’s an extremely effective mnemonic device and is still used by memory champions like Joshua Foer, author of the recent book, Moonwalking With Einstein.

To use the method of loci, the speaker concentrates on the layout of a building or home that he’s familiar with. He then takes a mental walk through each room in the building and commits an engaging visual representation of a part of his speech to each room. So, for example, let’s say the first part of your speech is about the history of the Third Punic War. You can imagine Hannibal and Scipio Africanus duking it out in your living room. You could get more specific and put different parts of the battles of the Third Punic War into different rooms. The method of loci memory technique is powerful because it’s so flexible.

When you deliver your speech, you mentally walk through your “memory house” in order to retrieve the information you’re supposed to deliver. Some wordsmiths believe that the common English phrase “in the first place” came from the method of loci technique. A speaker using the technique might say, “In the first place,” in reference to the fact that the first part of his speech was in the first place or loci in his memory house. Fascinating, isn’t it?

Helping Your Audience Remember Your Speech

For our communication to be truly persuasive and effective, we need to ensure that our audience remembers what we’ve communicated to them. The first step in getting people to remember what you’ve said is to have something interesting to say. If everyone in the audience is zoning out and playing with their iPhones, no amount of organizational tricks will help them remember your speech.

Once you’ve formulated an interesting message, follow the basic pattern set forth in the canon of arrangement to make your speech or text easy to follow and thus easy to remember. Give a solid introduction where you set out clearly what you plan on sharing with your audience. You can say something as simple as, “Today, I’m going to discuss three things. One, blah blah blah. Two, blah blah. Three, bloop bleep blah.”

Throughout your speech, stop and give your audience a roadmap of where you’re at in your speech. If you’ve just finished the first part of your speech, say something like, “We’ve just covered blah blah. We’ll now move on to my second point, blee blop.” This constant reviewing of where you’ve been and where you have left to go will help burn the main points of your speech into the minds of your audience.

As I also discussed in our article on the canon of arrangement, telling a captivating story is one of the best ways to draw your audience in and help them remember your message. You’ve probably seen the power of story in aiding memory in your own life. What’s easier? Reciting back to a friend what you learned in your physics class or reciting the storyline of a movie you just saw? My bet is on recalling the plot of the movie. Harness the power of story by weaving in anecdotes that bolster your point throughout your speech or text.

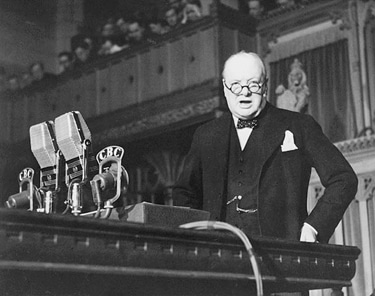

Another tool to make your rhetoric more memorable are figures of speech. We discussed these a bit in our article on the canon of style. A well-executed figure of speech can assure that your audience remembers what you’ve said. Take Churchill’s famous “We Shall Fight on the Beaches” speech. Most people can remember segments of this speech after hearing or reading it just once because Churchill masterfully used the figure of speech of anaphora. Anaphora calls for repeating a key word or phrase at the beginning of successive clauses. Check out this stirring section from that famous speech:

Even though large tracts of Europe and many old and famous States have fallen or may fall into the grip of the Gestapo and all the odious apparatus of Nazi rule, we shall not flag or fail. We shall go on to the end. We shall fight in France, we shall fight on the seas and oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air, we shall defend our island, whatever the cost may be. We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender, and if, which I do not for a moment believe, this island or a large part of it were subjugated and starving, then our Empire beyond the seas, armed and guarded by the British Fleet, would carry on the struggle, until, in God’s good time, the new world, with all its power and might, steps forth to the rescue and the liberation of the old.

See how many times he repeated the phrase “We shall fight?” Seven times. No wonder people remember what Churchill said. If you want people to remember what you say, do likewise.

Storing Up Quotes, Facts, and Stories for Future Speeches

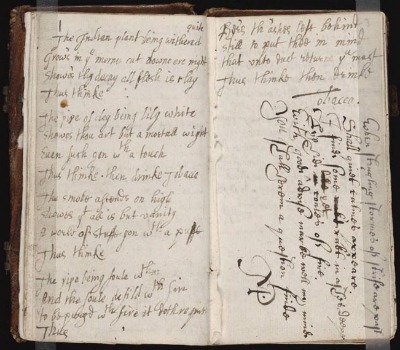

Commonplace book from the 17th century.

Another important part of the canon of memory is storing up information that can be used in future speeches or texts.

The ancient Roman and Renaissance rhetoricians encouraged the use of commonplace books to help facilitate this collection process and so do we. We’ve talked about the benefits of carrying a pocket notebook and the famous men who made pocket notebooks a part of their everyday arsenal before. If you’ve gotten into the habit, keep it up; if you haven’t, get started today.

Personally, my favorite notebooks to use are the thin Moleskine Cahiers that fit in my back pocket. If I have an idea or see or read something that I want to remember, I just whip out my notebook and scribble it down. A pocket notebook can be a storehouse for all the ideas you generate each day and for all the interesting thoughts and bits of advice you hear and read from other people.

Another tool I use to collect and organize all the information I gather is Evernote. Evernote is a free notetaking software that allows you to organize just about anything. At the end of each day, I’ll take the notes that I’ve made in my pocket notebook and type them into Evernote. Also, when I read a book, I’ll type sections or lines that I want to remember into Evernote before I return it to the library. Whenever I’m working on a speech or a post for the Art of Manliness, I’ll run a search through Evernote to see if I have anything in my personal library of quotes, figures, and stories. It makes putting together a speech or an essay much easier than starting from scratch.

Listen to our podcast with memory champion Nelson Dellis for even more tips:

Classical Rhetoric 101 Series

An Introduction

A Brief History

The Three Means of Persuasion

The Five Canons of Rhetoric – Invention

The Five Canons of Rhetoric – Arrangement

The Five Canons of Rhetoric – Style

The Five Canons of Rhetoric – Memory

The Five Canons of Rhetoric – Delivery

Logical Fallacies

Bonus! 35 Greatest Speeches in History