Do you sleep in fresh air? The average person will answer, ‘Yes.’ Nearly everyone has experienced the effects of sleeping in a closed room, and, in doing so, has roused with a feeling of suffocation or dull headache. An open window in the sleeping room seems almost a necessity. –Suburban Life Magazine, 1913

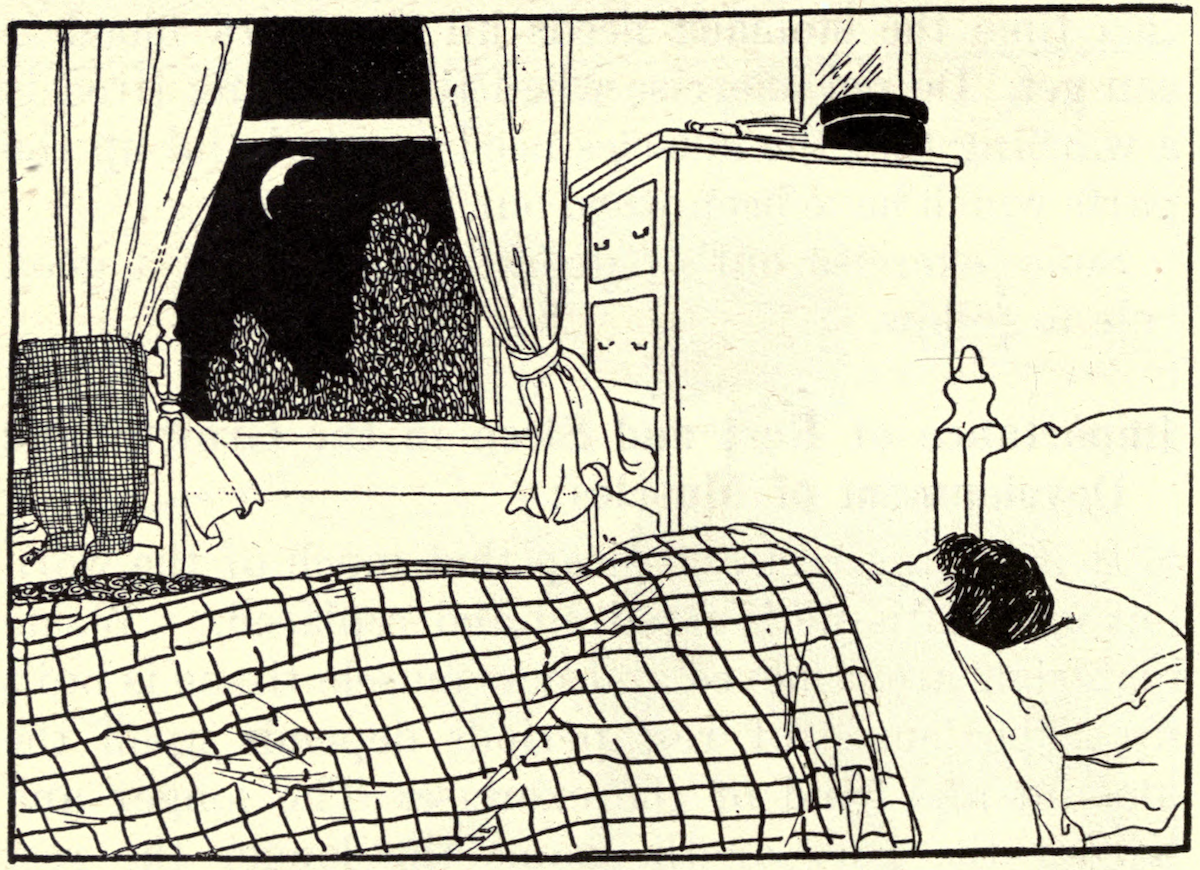

When Kate was growing up and would stay over at her grandparents’ house, her nana would always insist on keeping her bedroom door open when she slept. She’d turn on the fan too, and when the weather was nice, open the windows wide. Nana said that it wasn’t good to sleep in a stuffy, stagnant room and that maintaining airflow was a key to good health.

This view — especially the belief in the beneficial effects of breathing fresh air while you slept — was very common in the older generations, going back more than a century. Homes often included a screened-in sleeping porch, and if you could not avail yourself to this feature, it was recommended that you keep the windows of your bedroom open while you slumbered.

Creating this kind of circulation was of course a necessity in the summer in a time before air conditioning, but people often kept their windows open (if not as wide) even in the cold of winter, and even though it increased heating costs. According to a survey done by the Children’s Bureau of the U.S. Labor Department in 1923, 46% of children slept with the windows open only in summer, 52% slept with their windows open year-round, and only 2% slept with closed windows in every season. In winter, you simply wore warmer pajamas to bed and covered yourself with heavier blankets.

Sleeping with one’s windows open was so common because it was thought to not only improve the quality of sleep but make children and adults more rugged, strengthen the lungs, sharpen the mind, and keep sickness at bay. The commentary below, taken from a health bulletin from 1916, summarizes well the prevailing view:

Before we had houses, tuberculosis was unknown. Colds, pneumonia, grippe [influenza], and bronchitis were rarely heard of. But since we have become a race of shut-ins, and wedded house-creatures, afraid of and unused to fresh air, tuberculosis has become a veritable scourge with us. Pneumonia ranks second as a cause of death, while grippe and colds make their annual winter raids always leaving our death rate greatly increased. But houses are not always bad. It is the bad use we make of them. When we overcrowd them or fail to let out the foul, used up air as well as let in the sunshine and fresh air, then it were better from a health point of view that we lived out of doors.

Open air sleeping long ago proved its value as a cure for many diseases, particularly diseases of the nose, throat, and lungs, and now it is known to be even more valuable as a preventive of these conditions. . . .

Those who have really known the benefits of outdoor sleeping, and have enjoyed it because they were prepared for it, will never again be satisfied to breathe stale, indoor air while they sleep. They recognize at once the difference it makes in their mental as well as their physical feeling. Fresh air, aside from its value in curing and preventing respiratory diseases, is one of the best antidotes for mental sluggishness, physical bad feeling, and general inefficiency. Everybody should examine his sleeping quarters with reference to fresh air, and if he is not getting his share, he should make different arrangements.

While not all old-time health remedies have stood the test of time, the idea that sleeping with your windows open might be good for both body and mind has been at least partly backed by modern science.

To begin with, keeping the windows of your bedroom open can improve the quality of the air inside it. While we associate pollution with the environment outside our homes, indoor air can be polluted by “volatile organic compounds” or VOCs — emissions from your furniture, carpet, stovetop, cleaning products, air fresheners, and so on that have been linked to allergies, asthma, headaches, nausea, and throat and nose irritation.

Indoor air quality can further be compromised by a build-up of carbon dioxide. When you breathe, your lungs take in oxygen and expel CO2, and the concentration of the latter will increase if you’re in a closed-in room for a prolonged period of time.

Some research has shown that heavy concentrations of both CO2 and VOCs — at levels one might find in a crowded office meeting room or classroom — reduce productivity, decision-making, and problem-solving skills. On the flip side, studies have shown that improving ventilation in schools increases test scores and reduces absences.

This research was of course done with people who were awake, and spending time in a room with multiple other people. But it’s not too big a stretch to assume that, say, two people, sleeping together in a small, closed room for eight hours at a time, would experience the same reduction in air quality, and a similarly adverse effect on neural activity.

Second, while the health bulletin above may be overstating the effect of sleeping with open windows on the reduction of sickness, there is sound research which has shown that increasing the ventilation in a room does reduce the airborne transmission of disease. Viral particles expelled from coughing, breathing, and sneezing can remain suspended in the air for hours, and enhancing airflow dilutes the concentration of these pathogen-laden “droplet nuclei.”

This research is again not specific to conditions when you sleep, and it’s good to keep your windows open during the day too. But it may be particularly helpful when you’re lying motionless in a single spot, breathing in the same air for hours at a time.

Now these studies, while suggestive, certainly don’t prove that sleeping with your windows open will preserve or enhance your health. But the real reason to adopt the practice isn’t ultimately scientific, but experiential.

Anecdotally, I know when I sleep with the windows open at night, I sleep more deeply and restfully, and wake up feeling refreshed and in a better mood. Is it the constant influx of oxygen? The soothing symphony of night noises? Just something intangible about the effects of fresh air? Beats me, but it does seem to work.

Give it a try yourself. Nana would approve.

Be sure to listen to our podcast on how to get a better night’s sleep: