“The struggle between the autonomous few and the non-autonomous many — is only beginning.” –The Lonely Crowd

First published in 1950 as a sociological analysis of American life, The Lonely Crowd became a surprising bestseller; its authors, David Riesman and his collaborators, had expected it to be of interest only to fellow academics, and yet the book touched a nerve in the American public, resonating with a concern many felt about the changing character of the country.

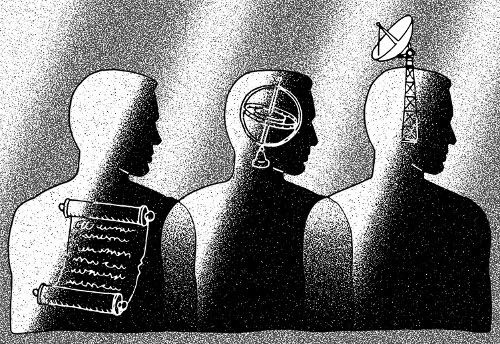

In the book, Riesman sets forth three types of “social character,” three mechanisms by which people conform to the society in which they live: tradition-directed, inner-directed, and other-directed.

The tradition-directed type dominates in primitive societies. Rituals, routines, and kinship ties ensure each generation does things as they have always been done.

The inner-directed type dominates in industrial economies. This type is guided by an inner set of goals and principles. These values are planted within the individual by his parents during his childhood, and act as an inner gyroscope – spinning throughout his life and keeping him on course. The inner-directed type is focused on producing more than consuming. He enjoys going it alone, and while he conforms his outward behavior to match societal norms, the opinions of others have little sway on his inner life. He would rather be esteemed than loved.

The other-directed type dominates in a service, trade, and communications-driven economy. This type is very sensitive to the preferences and expectations of others. He always has his antenna up to receive the signals of other people, and watches what they are doing, thinking, and feeling on his radar. The other-directed type is focused more on consuming than producing. He looks to his peers and the media for guidance on how to live and is group and team-minded. He would rather be loved than esteemed.

Riesman takes pains in The Lonely Crowd to point out that the above are types, not individuals, and that all societies and people are a mix of the types. This is not like a quiz in Cosmopolitan Magazine where you can figure out which one you are:

“There can be no such thing as a society or a person wholly dependent on tradition-direction, inner-direction, or other direction: each of these modes of conformity is universal, and the question is always one of the degree to which an individual or a social group places reliance on one or another of the three available mechanisms. And you can move from greater dependence on one to greater dependence on another during the course of your life.”

Also, knowing that most people would be drawn to the cowboy-esque inner-directed type, he stresses that the inner-directed are no “better” or less conformist than the other-directed. For while the inner-directed sticks by his internal gyroscope, that gyroscope was implanted by his parents; he lives their values, not his.

Instead (and this often gets ignored), at the end of The Lonely Crowd Riesman argues that the ideal to strive for is a fourth type: the autonomous.

The autonomous has “clear cut, internalized goals,” but unlike the inner-directed, he chooses those goals for himself; his “goals, and the drive toward them, are rational and non-authoritarian and not compulsive.” He can cooperate with others like the other-directed, but “maintains the right of private judgment.” He’s involved in his world, but his “acceptance of social and political authority is always conditional.”

Essentially, the autonomous “are those who on the whole are capable of conforming to the behavioral norms of their society…but are free to choose whether to conform or not.” The autonomous stands outside and above the other types; he understands them, can reflect on them, and then can freely choose when and if to resist them or act in accordance with them. He is able to transcend his culture—by turns overruling it and joining in with it as he himself chooses in order to further his goals. The autonomous man is both idealistic and pragmatic.

Riesman argued that societies tend to move from tradition-directed, to inner-directed, to other-directed as they develop. At the time The Lonely Crowd was published, he posited that most of the country remained inner-directed, but observed the growth of the other-directed among the upper-middle classes along the coasts and in urban areas. He predicted that the other-directed type would continue to expand and become the country’s dominant mechanism of social character.

In this prediction, and many others, Riesman was quite prescient. In today’s society, other-direction represents the chief mode of conformity and pulls at us in ways that Riesman could not have imagined. The man who wishes to become autonomous must understand what those ways are, so that he can reflect upon them, transcend them, and choose to conform with them only when he truly wishes to do so.

Challenges to Autonomy in the Modern Age

Socialization Through Taste and the End of Privacy

Inner-directed types flourish during periods where society places a good deal of importance on etiquette, while other-directed types rise when the rules of etiquette have waned.

This may seem contradictory; after all, aren’t those who are concerned about etiquette the kind of people who care a lot about what others think of them? This is how we see etiquette through a modern lens, and following the rules of etiquette could certainly bolster your reputation with others back in the day. But etiquette could also be used as a buffer by the inner-directed to keep people at arm’s length and to guard one of the inner-directed’s most prized possessions: his privacy. Riesman argues that “Formal etiquette may be thought of as a means of handling relations with people with whom one does not seek intimacy…Thus etiquette can be at the same time a means of approaching people and of staying clear of them.”

In a largely other-directed society, training in etiquette is replaced with training in consumer taste. Other-directed individuals define themselves by their taste in music, food, travel, and so on, and find marginal differences between their own tastes and the tastes of others in order to differentiate themselves from their peers. Socialization among the other-directed centers on “feeling out with skill and sensitivity the probable tastes of the others and then swapping mutual likes and dislikes to maneuver intimacy.” Did you like that movie? Have you heard of this band? Do you like this restaurant? Have you seen this funny Youtube clip?

This “swapping of mutual likes and dislikes to maneuver intimacy” has of course taken an exponential leap forward since Riesman’s day with the advent of social media. Sites like Facebook and Pinterest exist almost exclusively to foster this kind of interaction, allowing users to display their tastes and see if they get a thumbs up from others.

Riesman argues that “this continual sniffing out of other’s tastes,” becomes “a far more intrusive process than the exchange of courtesies and pleasantries required by etiquette.” In the days of inner-direction, “certain spheres of life were regarded as private: it was a breach of etiquette to intrude or permit intrusion on them.” In contrast, in an other-directed society “one must be prepared to open upon cross-examination almost any sphere in which the peer-group may become interested.”

This opening up of every sphere of your life to the public is today called “transparency,” a buzz word these days for those who seek “authenticity.” Social media has allowed people to share many more personal details with a much wider group of peers, extending far beyond one’s intimate friends and family. Those who like to keep some things private, who enjoy sometimes being alone, and who are not as connected (“He doesn’t have a Facebook account???”) are viewed with suspicion.

A Lack of an “Enemy” to Rebel Against

Autonomy , Riesman argues, “must always to some degree be relative to prevailing modes of conformity in a given society; it is never an all-or-nothing affair, but the result of a sometimes dramatic, sometimes imperceptible struggle with those modes.”

And herein lies one of the biggest difficulties in becoming autonomous in our day and age: with such a great diversity of groups and opinions and lifestyle choices, and without any real agreed upon social norms or expectations these days, there aren’t any true “enemies” to rebel against anymore. This is why, Riesman argues, it was easier to be autonomous in an inner-directed society, for the would-be autonomous during such periods “had no doubt as to who their enemies were: they were the adjusted middle-class people who aggressively knew what they wanted, and demanded conformity to it–people for whom life was not something to be tasted but something to be hacked away at.”

The counterculture movement of the 60s and 70s represented an effort by nonconformists to throw out the gyroscopes their parents had planted within them and rebel against what was perceived as suffocating middle-class values in order to pioneer a world where people were free to act and choose whatever lifestyles they wanted.

But now those battles have almost entirely been won—the idea that you should live authentically and do your own thing is the modern zeitgeist. We live in an Age of Anomie where there are very few cultural expectations for how people should live their lives.

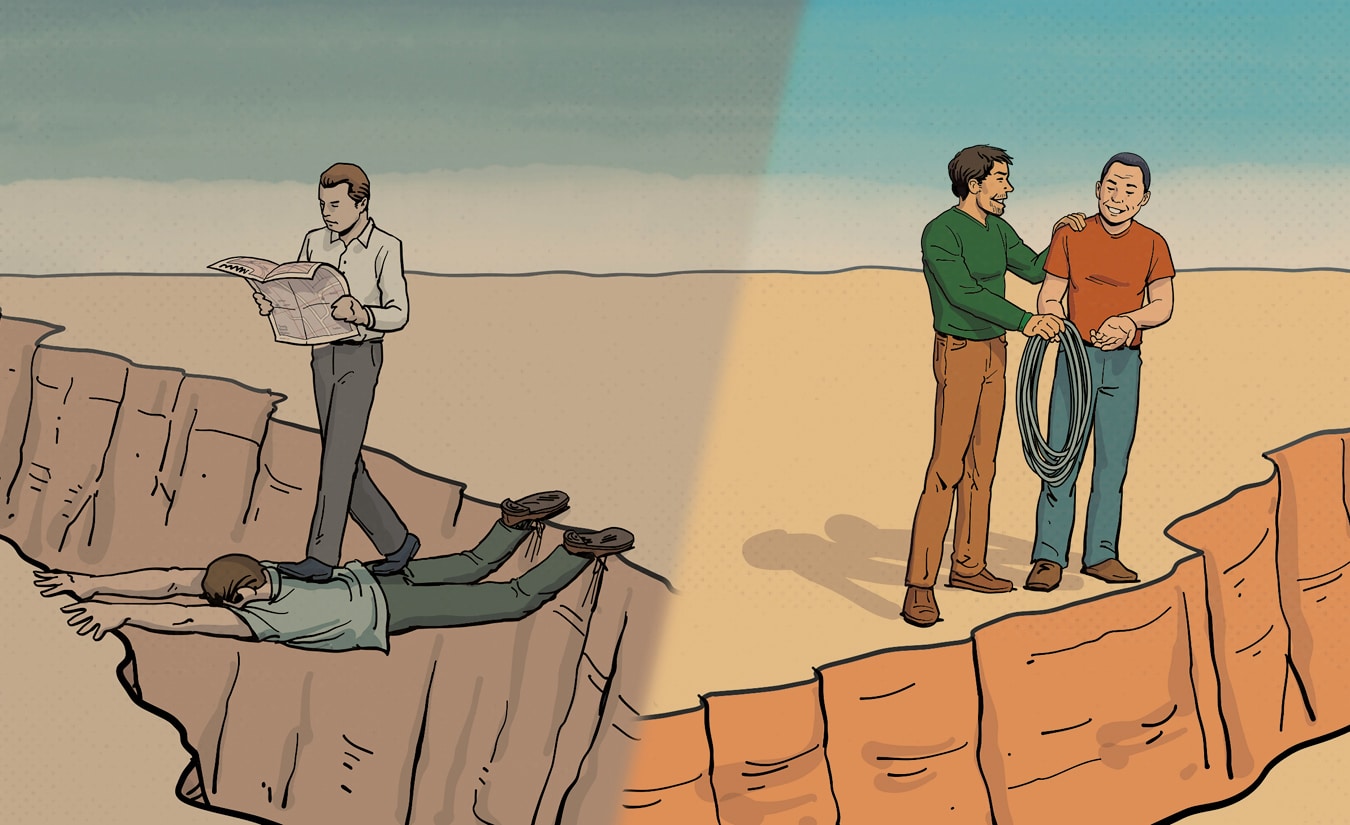

Without a clear “enemy” to define themselves against, people often fall into two traps.

The first is continuing to fight the same battles the counterculturalists of the 60s did, even though those battles were won decades ago. For example, Antonio’s post about wearing shorts caused a great deal of consternation, and bred some reasonable dissension, but also garnered a peculiar kind of comment which went something like this: 1) “Everybody I know wears cargo shorts and t-shirts,” AND 2) “I would never follow silly rules like this about what I wear—I’m a nonconformist!” Of course both premises can’t be true! Dressing only according to the dictates of your personal comfort would have been rebellious 50 years ago, but in a culture where few rules or expectations still exist about style, it’s not something you can stake your autonomy on anymore. If anything, the man who dresses more formally in a very casual society has a better claim to rebelling against societal norms. How a man dresses — or for that matter marries, or has sex, or makes money — is no longer a reliable measure of his autonomy.

The second false way of attaining autonomy in an other-directed world without a clear enemy, Riesman argues, is to become part of a peer group that thinks of themselves as nonconformists, but who “are not necessarily free, as they are often zealously tuned into the signals of a group that finds the meaning of life, quite unproblematically, in an illusion of attacking an allegedly dominant and punishing majority…young people today can find, in the wide variety of people and places of metropolitan life, a peer-group, conformity to which costs little in the way of search for principle.”

Lifestyle Inflation

Another of the boogeyman relics left over from the 60s that modern autonomy-seekers build their identity around fighting is the striving for the “American Dream” of a house in the suburbs and a wife and kids. These “rebels” join with the like-minded in pursuing “lifestyle design,” which encompasses all sorts of goals but mainly revolves around being able to follow your passion, quit your day job, still earn a good (passive) income, and travel around the world.

While at first blush this goal would seem to be very inner-directed, it’s actually a pursuit that’s rapidly risen in popularity because of our culture’s move towards other-direction.

The old school inner-directed type sought after “stuff:” cars, house, wealth. These were the tangible goals that the gyroscopes planted by their parents told them were the symbols of success. The inner-directed conformed to others and kept up with the Joneses when it came to external things—but did not let others influence their inner values nor the arc of their lives.

The other-directed, on the other hand, seek experiences over stuff. This can certainly be seen as a better, less consumeristic aim. But for the other-directed, their drive towards these experiences does not come from within, but from watching other people. For the other-directed do not just conform to others as far as external behavior, but also seek to match the quality of other people’s inner experiences. They look to others for “what experiences to seek and in how to interpret them.”

When they feel they’re not on the right course, the tradition-directed feel shame, the inner-directed feel guilt, and the other-directed feel anxiety. And never does this anxiety rear its head more than when the other-directed see the different experiences that others are having. They look at Facebook and see a friend traveling the world, or partying in Vegas, or skydiving in South America, and wonder “Is my life less satisfying?” “Should I be living more deeply than I am?” “Is everyone happier than I am?” The resulting anxiety and restlessness can have the positive effect of motivating a man to get outside of his comfort zone and try new things, but it can also make him feel unhappy about his life choices, even if he made those choices willingly, consciously, and in line with his authentic desires. It can also keep him from making a choice he really wants, for he’s unsure of how it stacks up to what others are doing.

Other-Directed Entrepreneurship

In an age of the other-directed, starting your own business seems like a good option for becoming more autonomous. And yet other-directedness has seeped into this area of life as well.

Whereas the inner-directed producer of old concentrated his efforts on crafting and offering a superior product, much of entrepreneurship these days depends on interpersonal relationships, popularity, and building a “personal brand.” Entrepreneurs are oftentimes selling themselves more than their products and thus feel that they must always be friendly and nice to others in hopes that they’ll be converted into fans or customers. Or as Riesman puts it, “Obliged to conciliate or manipulate a variety of people, the other-directed person handles all men as consumers who are always right.”

For example, something I’ve noticed about other bloggers who are hoping to build their reader base, is that even when someone leaves them a wholly inaccurate and asinine comment, the blogger will not reply by telling him to shove off or ignoring it altogether, but by saying something like, “Hey man! Sorry that we disagree. But thanks a ton for visiting and I hope you come back soon!”

Endless Feedback

I think the greatest challenge to not unthinkingly slipping into a wholly other-directed life is the amount of feedback from others that’s available to read and listen to in the modern age. Do you eagerly wait to see what people will say about your Facebook status or photo? Do you spend more time reading the comments on online articles than you do thinking about it yourself? Or perhaps you skip the article altogether and just read what other people have to say? Do you read the comments on a video while you’re “watching” it, thus letting others influence your perception of it before you reach your own conclusion? When you leave a comment on something, do you keep checking back to see what other people thought of what you had to say? Do you read reviews of books or music before you buy them, and then afterwards as well, to see if other people felt the same way about it as you did?

Conclusion

Now that we’ve gone through some of the challenges to becoming autonomous in our other-directed age, it’s important to reiterate that other-direction is not necessarily a bad thing. The point is rather that you must be aware of its pull so that instead of letting it dominate your life, you are able to transcend and rise above it. Only by understanding something, can you free yourself from it. Then, from this position of freedom and autonomy, you can choose when to conform on your terms (in cases where it furthers your goals and principles, or even simply brings enjoyment), and when to resist.

Let’s close with a quote from Riesman:

“If the other –directed people should discover how much needless work they do, discover that their own thoughts, and their own lives are quite as interesting as other people’s, that, indeed, they no more assuage their loneliness in a crowd of peers than one can assuage one’s thirst by drinking sea water, then we might expect them to become more attentive to their own feelings and aspirations.”

Illustration by Ted Slampyak