Several years ago I was wandering the stacks at the University of Tulsa library when I happened to chance upon an old, pink book with the words “Police Gazette” gilded on the spine in fancy script. I don’t know why, but I took it off the shelf and started to thumb through it. Inside I found page after page of 19th-century newspaper re-prints that featured big, bold, and inflammatory headlines along with cool illustrations of bare-knuckle pugilists, old-time strongmen, and lots of women in bloomers slugging each other senseless.

Little did I know that the musty book in my hands was a collection of facsimiles of America’s first hugely popular men’s magazine: The National Police Gazette. Intrigued by what I saw in the book, I began researching the history of the Gazette and discovered that it was the magazine of American men living in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Not only was the Police Gazette insanely popular, but it played a large role in shaping modern America’s idea of rugged and rebellious manhood and pioneered the pillars of much of today’s male-orientated media. The Police Gazette’s content consisted of a mish-mash of true-crime stories, gossip, sports, and pictures of buxom babes; basically, it was Sports Illustrated, National Enquirer, and Maxim rolled into one weekly magazine.

Below I give a brief history of this virile magazine that was, according to scholar Howard P. Chudacoff, “the unofficial scripture of the bachelor subculture” during the Golden Age of the American Bachelor. I’ve also included some of the amazing wood-engraved illustrations to give you a glimpse of a magazine that your great-great-great-grandpa probably thumbed through while waiting to get a shave at the barbershop.

The History of the National Police Gazette

Origins

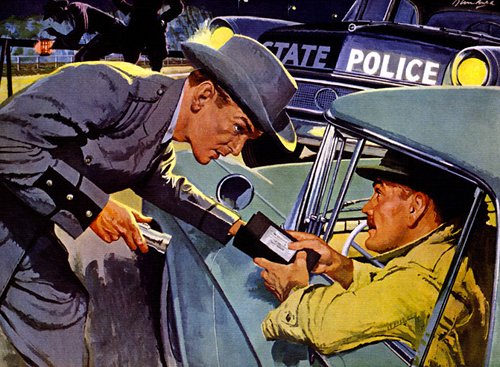

The National Police Gazette was founded in New York City in 1845 by journalist George Wilkes and attorney Enoch Camp. The Gazette’s early issues were dedicated to giving extremely detailed crime narratives, and Wilkes and Camp claimed they printed the magazine to help police officers recognize criminals and bring them to justice. Of course they were also simply trying to cash-in on the American public’s growing interest in tawdry and sensationalist tabloid news. In keeping with their publication’s stated mission of helping cops catch crooks, each issue contained lists of names of alleged offenders, their aliases, physical appearances, and in some cases even their home addresses.

The Police Gazette experienced mild success under Wilkes’ and Camp’s leadership. However, they eventually sold the rag to former New York City police chief George Washington Matsell in 1856. Matsell made three changes that propelled the magazine to national popularity. First, he expanded story coverage to include lurid sex crimes and gossip about the sexual affairs of New York’s dignitaries. Second, Matsell introduced what would become a defining feature of The National Police Gazette: full page, wood-engraved illustrations. Up until this innovation, the Gazette consisted of page after page of intimidating blocks of text. By illustrating the content with vivid engravings, Matsell hoped to add not-so-literate readers to his subscriber rolls. Finally, Matsell aggressively expanded the number of correspondents working for the magazine and eventually had reporters in every major U.S. city.

Unfortunately, Matsell’s wholesale expansion eventually forced him to sell the publication in 1866, as he could no longer afford to fund its huge budget. After the sale, the Police Gazette entered a decade-long slump of declining circulation and ad sales and was on its way to being thrown in the dust bin of history. Things quickly changed, though, when a scrappy Irish immigrant named Richard Kyle Fox joined the magazine’s team.

Becoming the Bachelor Bible

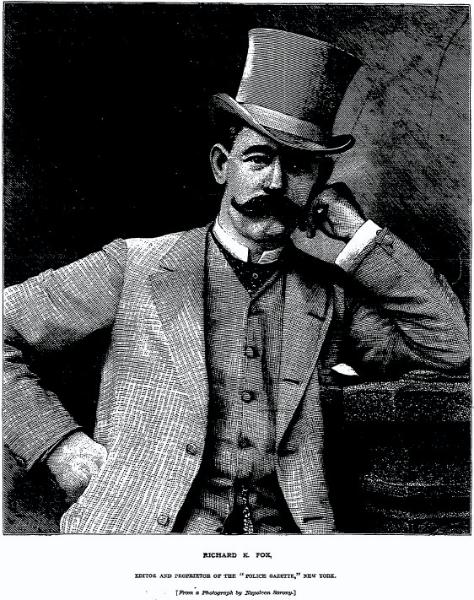

From policegazette.us

Fox was a character straight out of a Horatio Alger story. He arrived in the United States from Ireland in 1874 penniless but full of ambition. Needing a job, he began selling ads for the Police Gazette. While the job didn’t pay well, Fox hustled and quickly became the magazine’s business manager in just a year. Although the Gazette continued to struggle, Fox felt it was capable of becoming a media juggernaut. After somehow convincing a bank to loan him the money, he bought the publication in 1877, named himself editor-in-chief, and made changes that would transform the The National Police Gazette into America’s first widely popular men’s magazine.

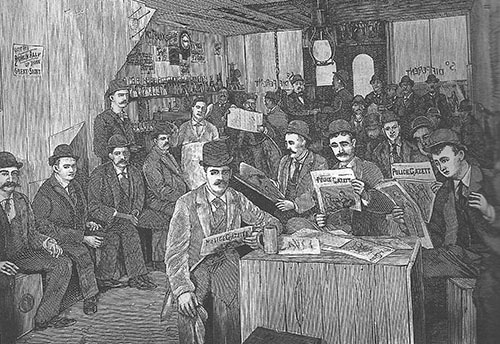

Men reading “the bachelor bible” in a saloon.

First, Fox reduced subscription rates for saloon keepers, barbers, and hotel managers — business owners that happened to cater to the Police Gazette’s target audience of young, single, urban men. Second, Fox further increased the number of illustrations and effectively created the men’s magazine tradition of featuring sexy layouts of women by introducing his “Footlight Favorites” — engravings of buxom burlesque dancers and soubrettes who showed an occasional bare arm or ankle (*wolf whistle* *cat call* *drooling*). Third, noticing America’s increasing interest in sports, Fox had the vision to create America’s first journalistic sports department in 1879 and wrote full-page stories about boxing, football, and baseball. Fourth, to provide stories for his magazine and to curry favor with his readers, Fox began sponsoring boxing prize fights. Finally, ever the marketing and branding master, Fox began printing the Police Gazette on distinctive pink paper that became a trademark for the magazine. Fox framed all these new additions and features with a cheeky irony and humor that made the magazine an easy and entertaining read.

Fox’s changes to the magazine paid off big time. In just a few short years he tripled the circulation from what it was under Matsell and ad revenue was on par with some of the largest and most popular magazines of the time. Alternatively referred to as the “bachelor bible” and the “barber shop bible,” circulation reached 150,000 a week, with special issues snatched up by more than 400,000; and these numbers really understate the magazine’s reach, as one copy of the Gazette might be read by a hundred men at a saloon or barber shop. The magazine was so firmly established as a fixture in the latter that a common joke sprung up that went like this: “Did you read The National Police Gazette?” “No, I shave myself.” (yuk, yuk, yuk.)

Decline

Beginning in the 1900s, the Police Gazette’s popularity waned as competitors copied features once unique to its pages. Many of these new imitators were the big, respectable daily newspapers that once thumbed their noses at the magazine’s low-brow content. Seeing the demand for sports news, large newspapers began their own dedicated sports sections and full-time sports departments. The sports coverage from these larger newspapers often surpassed that of the Gazette. Moreover, these same large, respectable newspapers began publishing the kind of tawdry stories that had been the Gazette’s bread and butter.

By the 1920s, the Police Gazette was on life support. When Fox died in 1922, the plug was pulled. Without his charismatic leadership (and with saloons shutting down because of Prohibition, the magazine withered in circulation and readership. By 1932, it went bankrupt and was sold to another publisher. For the next four decades several publishers tried to revive this once notorious magazine, but with competition from glossier, more niche magazines like Sports Illustrated and Playboy, the Police Gazette, after churning out 5,000 issues over 130 years, ceased publication altogether in the 1970s.

Today there’s a website that continues to publish under The National Police Gazette name. The articles on the site hit the same themes as the 1890s pink-papered version. In addition to creating new sensational content that Richard K. Fox would be proud of, the site is dedicated to researching and preserving the history of the Police Gazette. Definitely recommend checking it out, especially the history section.

Examples of Police Gazette Content

Below are some examples of the type of content you’d find in The National Police Gazette.

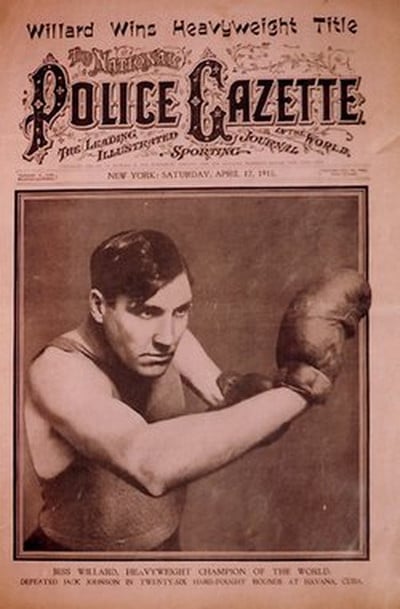

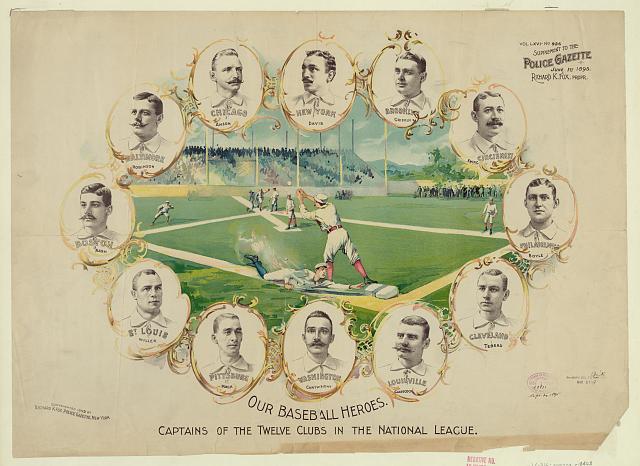

Sports

Sports coverage made up a large part of the content in the Gazette, with boxing getting the lion’s share of the attention. When the magazine started, boxing was not yet legal in the States. The magazine filled an untapped niche by covering the details of the nonetheless enormously popular underground matches.

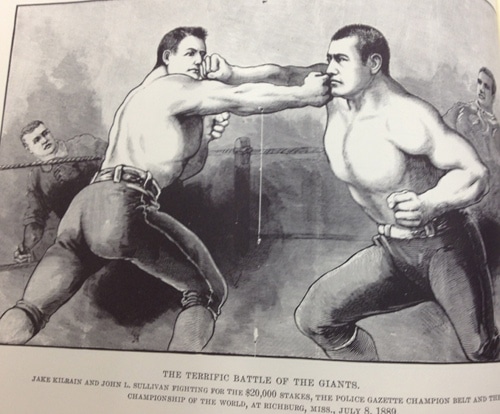

Image depicting John L. Sullivan and Jake Kilrain battling for the “Championship of the World.” Until the formation of the National Boxing Association in 1920, the Police Gazette was the organization that determined “world champion” boxers.

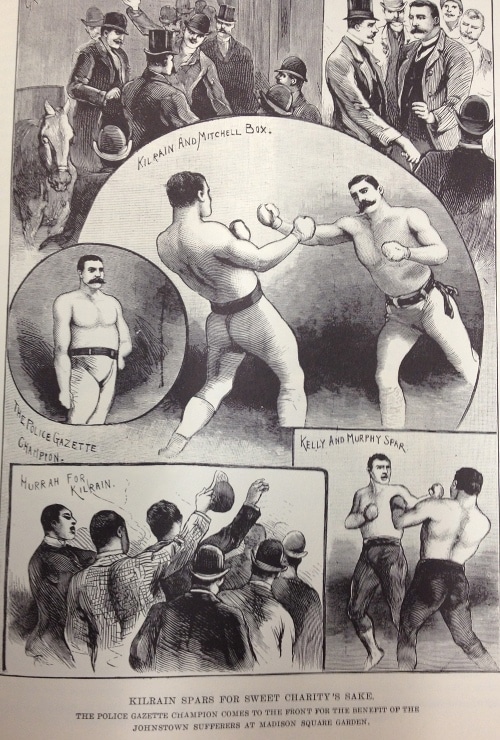

Jake Kilrain fighting in a charity fight for the victims of the Johnstown Flood in Johnstown, PA. The flood was one of the worst disasters in American history, killing over 2,000 people and causing upwards to $425 billion (in 2012 dollars) in damage.

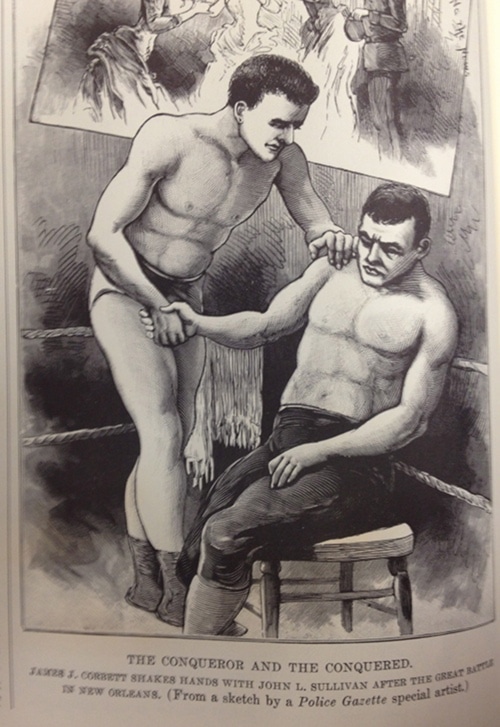

Image depicting John J. Corbett (“Gentleman Jim”) defeating John L. Sullivan. It was Sullivan’s only defeat during his long career. That match was also his last. Richard Fox and John L. Sullivan had an ongoing public feud that was likely exaggerated to drum-up publicity for both parties. The Police Gazette would snub Sullivan by consistently backing Sullivan’s opponents and downplaying his victories.

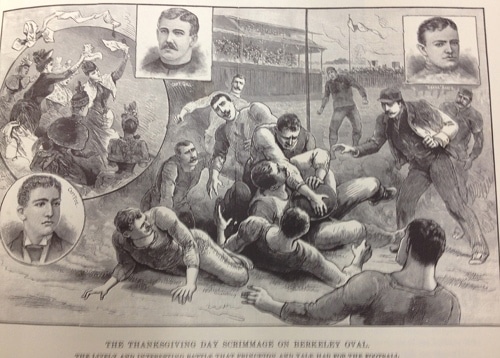

Football scrimmage on Berkeley Oval at Yale College.

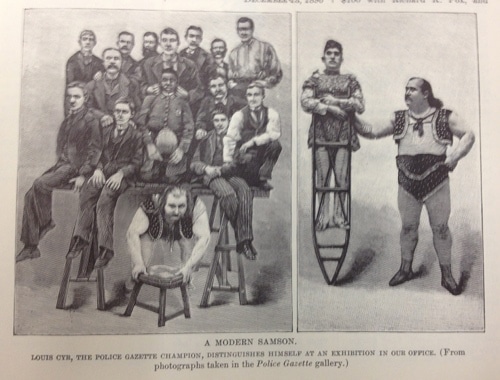

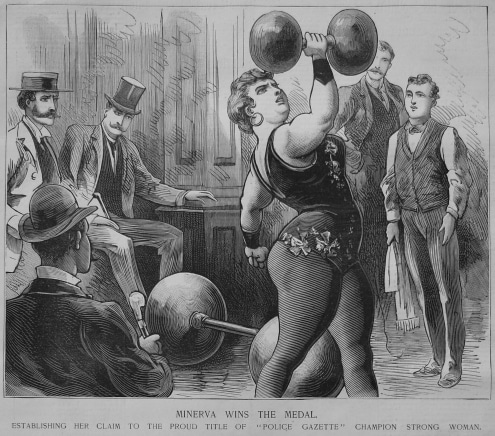

In addition to sponsoring boxing matches, the Police Gazette would also sponsor strongman events. Above is a winner of one such event.

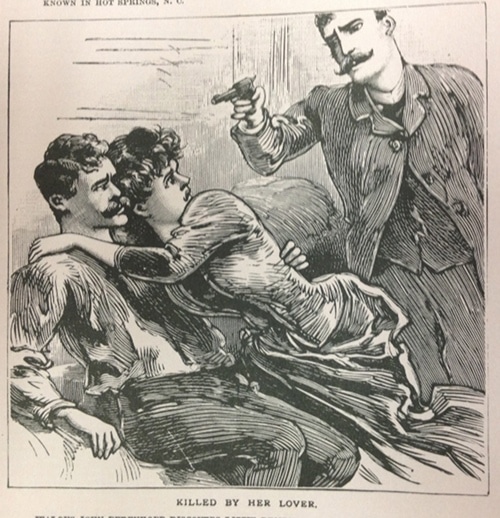

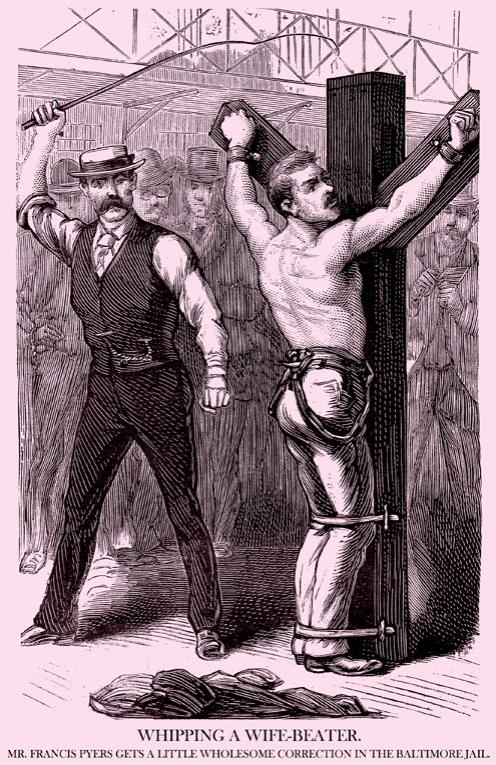

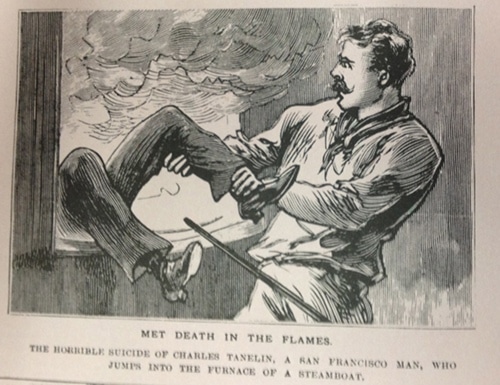

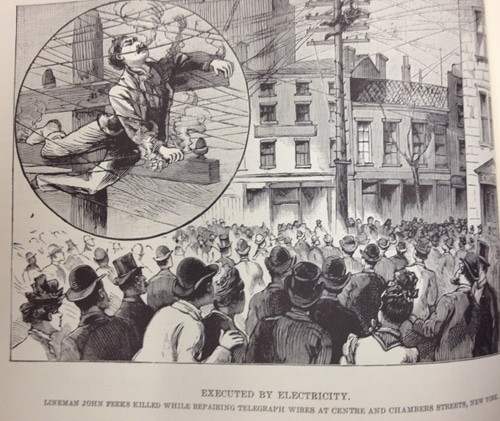

Crime & Violence

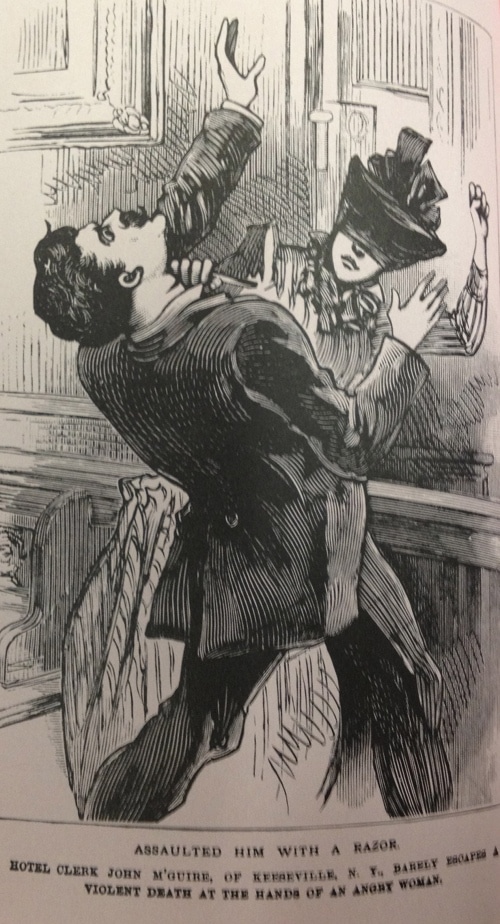

Crime stories, particularly those involving some sort of love triangle, sensational woman-on-man violence, or gruesome deaths, made the Police Gazette famous in its heyday.

Scorned woman creeps in with a knife to kill her husband and his lover.

Another philanderer attacked by an angry woman. This gal went after this gent with a straight razor. The man survived. I imagine the relationship did not.

Mustached man catches his gal in flagrante delicto with another mustached chap. Shoots them both.

From policegazette.us

Telegraph repairman electrocuted to death after falling into electric and telegraph lines. A bunch of people watch.

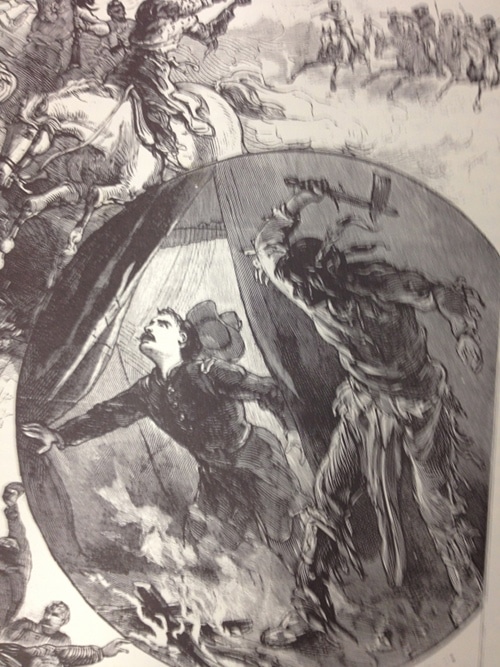

The Police Gazette of the 19th and early 20th century was often racist and xenophobic, playing on this fear to drum up readership. Common stories featured minority-on-white crimes and violence. This is an illustration depicting a story about an Indian raid on a U.S. Army calvary unit.

Illicit Activities of the Sporting Male

Besides sports like boxing, baseball, and football, the Police Gazette covered illicit activities that 19th century working-class men enjoyed watching and gambling on.

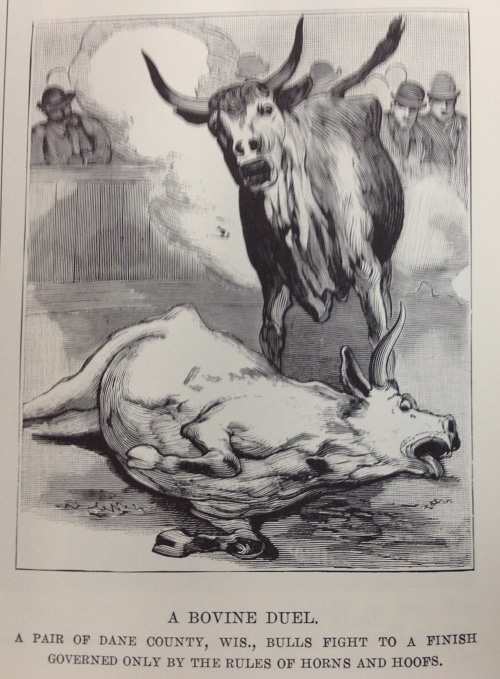

Two bulls enter; only one leaves.

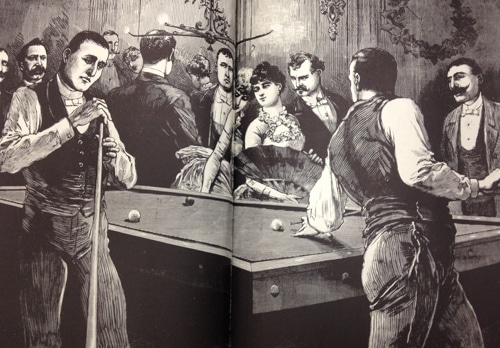

Pool halls were a popular bachelor hangout in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Legendary pool champion Wimpy Lassiter said this about pool halls of the period: “A long time ago I used to stand there and peek over the lattice work into that cool-looking darkness of the City Billiards in Elizabeth, North Carolina… And it seemed as though the place had a special sort of smell to it that you could breathe. Like old green felt tables and brass spittoons and those dark polished woods. Then a bluish haze of smoke and sweet pool chalk, and strongest of all, a kind of manliness.”

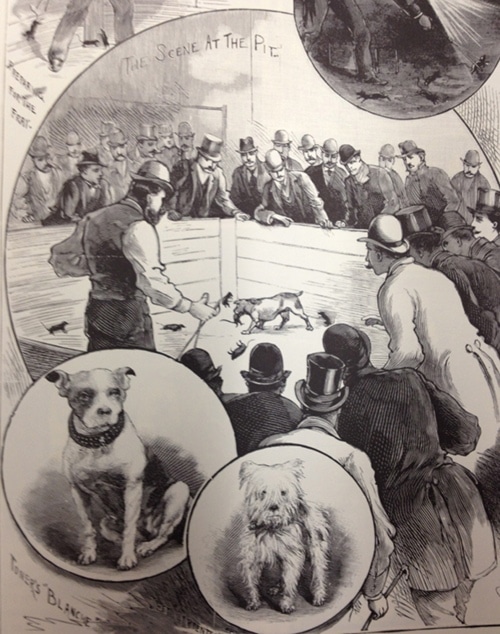

So, rat killing was a thing men gambled on back in the 19th century. They’d get some cute dogs and put them in a pen with a bunch of rats. Whichever dog killed the most rats won. I guess you had to get creative to entertain yourself when you didn’t have fantasy baseball.

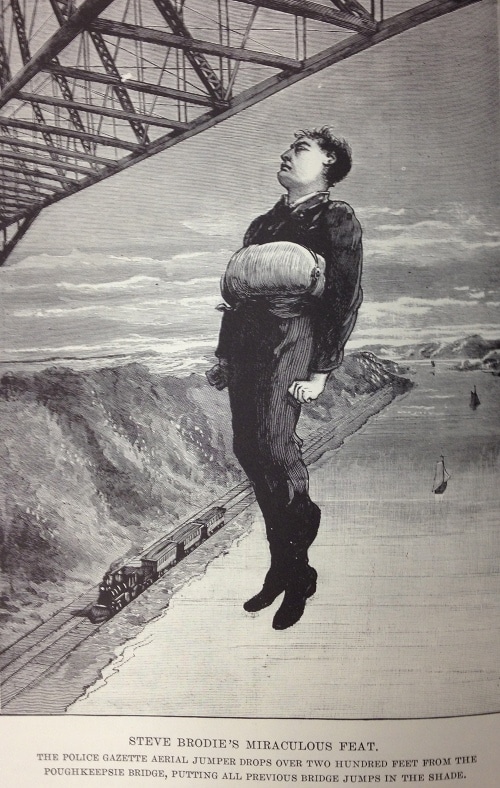

The Police Gazette covered all kinds of weird competitions (like water-drinking or egg-eating contests), record-setting feats, and stupid human tricks. Bridge jumping was a popular event back in the 19th century. People would try to outdo each other by jumping from higher and higher bridges.

From policegazette.us

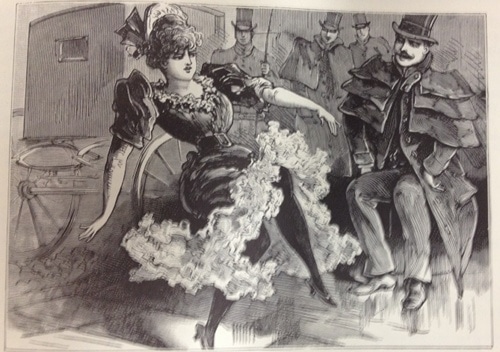

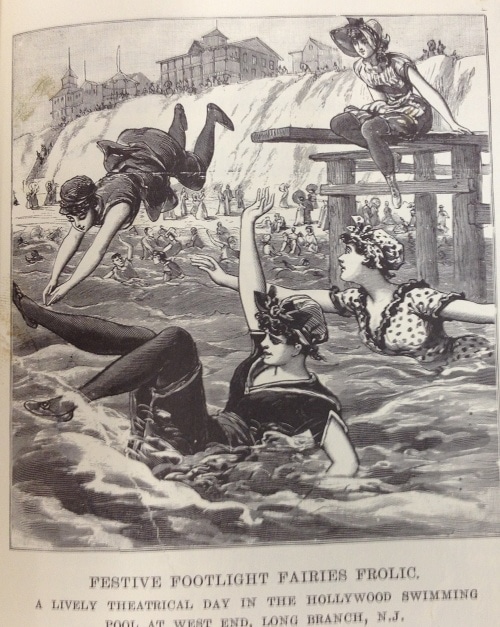

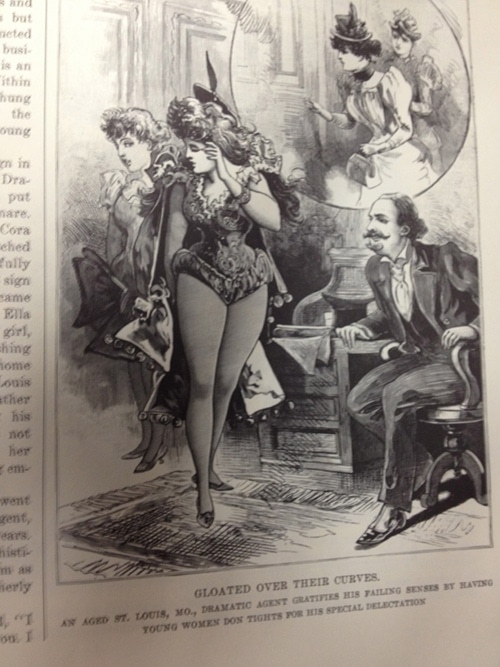

Buxom Babes in Their Bloomers

Showcasing scantily clad women was a common feature in the Police Gazette, and by scantily I mean the occasional bare arm, ankle, and cleavage. By today’s standards it was pretty tame stuff, but at the time it was envelope-pushing, particularly for a weekly periodical sold to the public. In the 1880s, Fox began a feature called “Footlight Favorites” in which he dedicated an entire page to an illustration of an attractive young woman. Yeah, The National Police Gazette invented the Centerfold Girl. And it paved the way for near-nude women to be a mainstay of most men’s magazines — the Art of Manliness that odd exception.

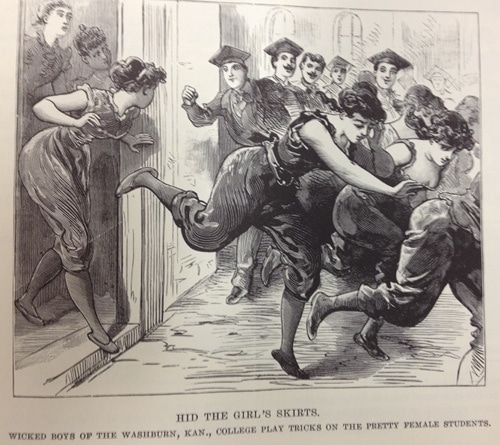

Foreshadowing Animal House, a group of college men pull a prank on their female classmates.

“My milkshake brings all the mustaches to the yard…”

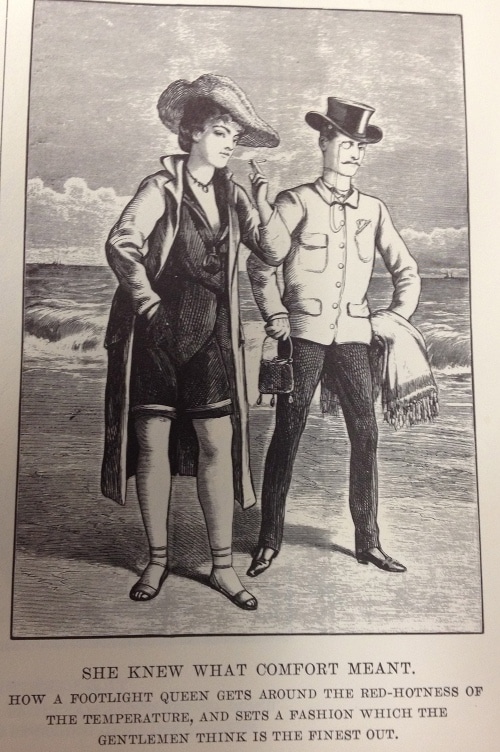

A few Footlight Favorites frolicking in their swimsuits. Hubba hubba.

I’m not sure what’s going on here except that lady’s bosom is coming dangerously close to being revealed!

Caption: “An aged St. Louis, MO. dramatic agent gratifies his failing senses by having young women don tights for his special delectation.” Creepy.

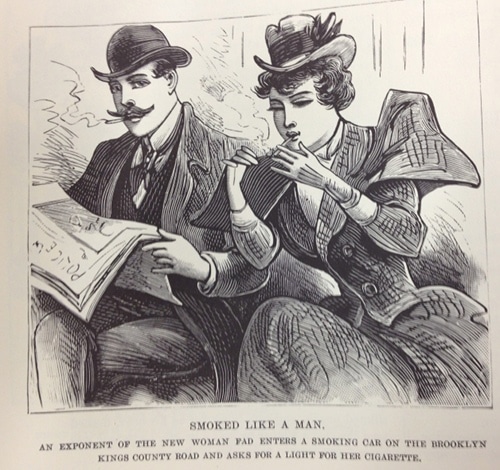

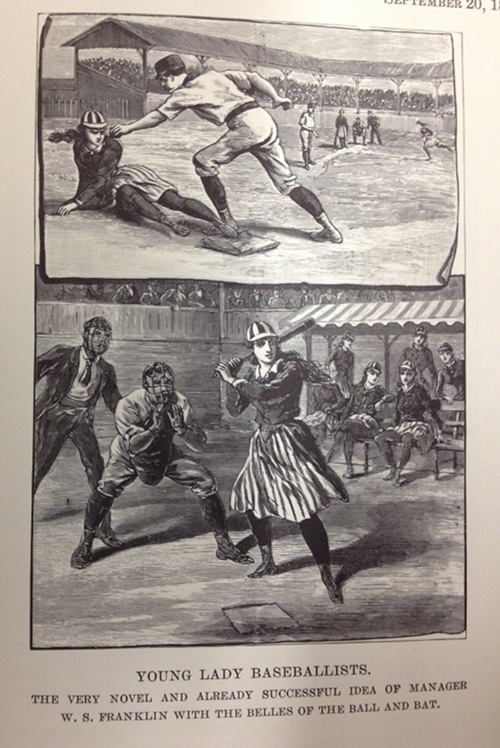

Ladies Doing Manly Things

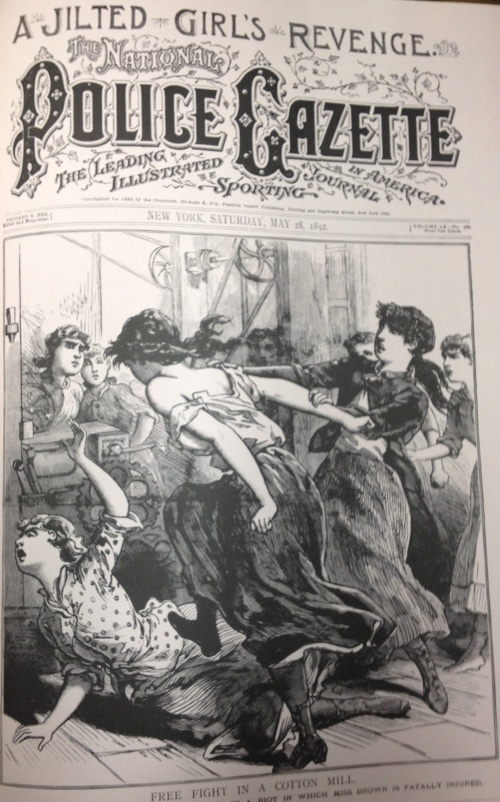

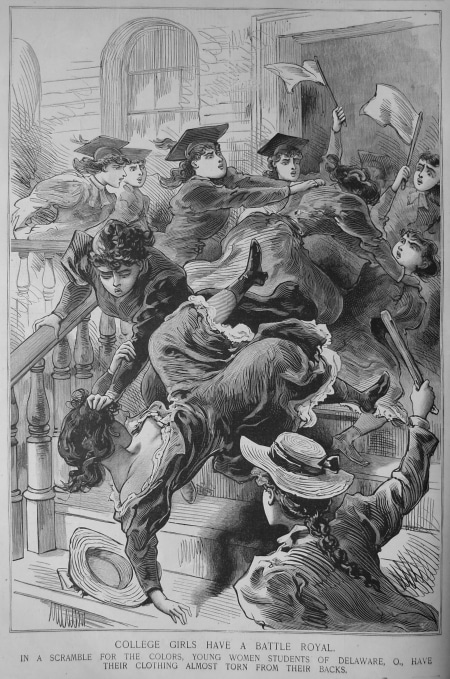

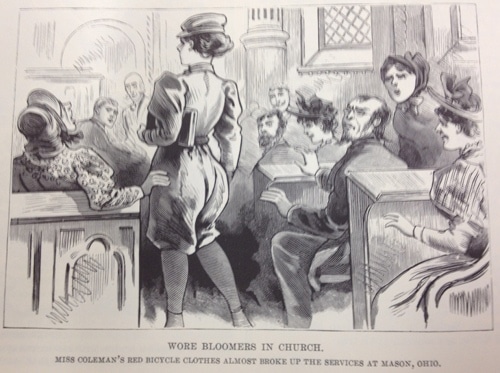

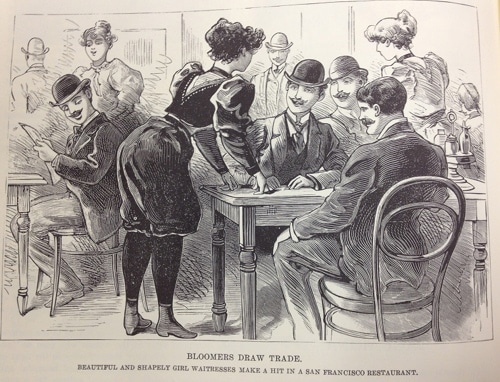

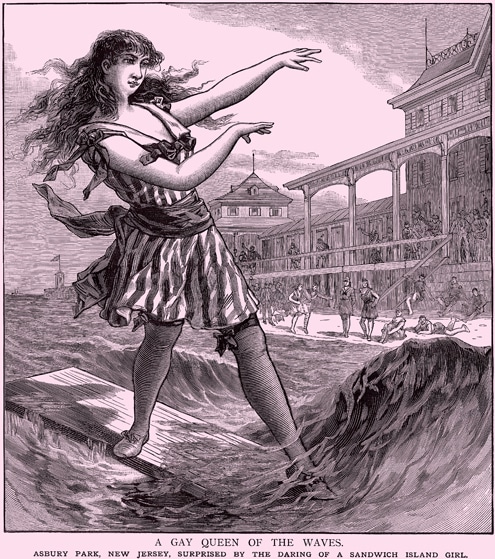

When readers weren’t ogling the Gazette’s lineup of “Footlight Favorites,” they were marveling at women doing uncharacteristically masculine things for the time, like smoking, fighting, and wearing pants. 120 years ago stuff like this was shocking, fascinating, and apparently newsworthy. Here are a few of my favorite illustrations of ladies doing manly things.

“A League of Their Own” has nothing on these dames. Also, we need to resurrect the word “baseballist.”

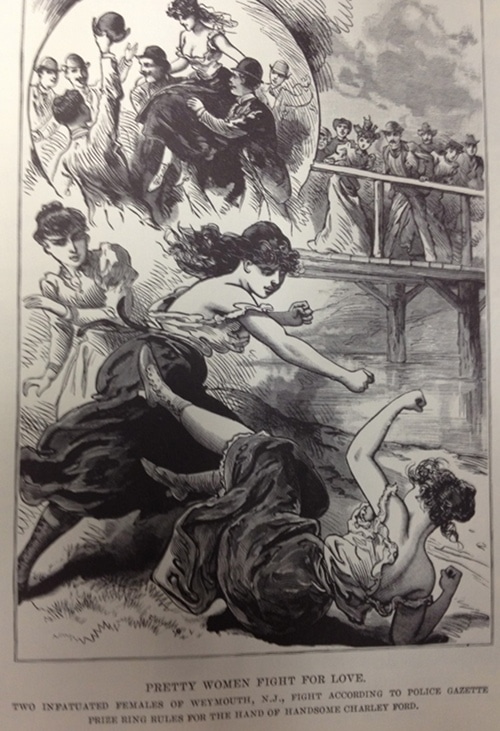

Girl fight! Girl fight! Of course, their clothes are coming off. Of course.

Brawling wasn’t limited to working-class women, as shown by this co-ed battle royal. And here you thought women of the time were always sweet and demure… (from policegazette.us)

This is the best one. “Wore Bloomers in Church.”

Today men ogle women in yoga pants; 120 years ago men ogled women wearing pants, period. I guess this was the Hooters of the day.

From policegazette.us

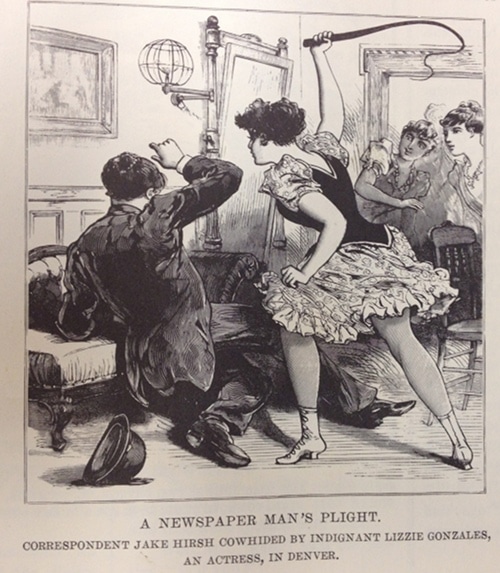

Class conflict was a common theme in the Police Gazette. To appeal to their primarily blue collar audience, the Police Gazette frequently featured stories of working-class women going to town on a white collar man. It was kind of titillating, and the implication was that soft-handed office workers were losing their blue collar ruggedness and becoming effeminate.

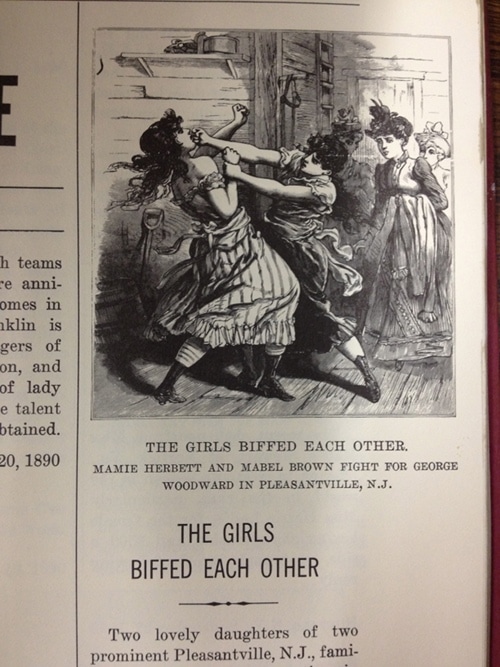

More fighting.

And more fighting. Also, “biffed” is another word that needs to make a comeback.

From policegazette.us

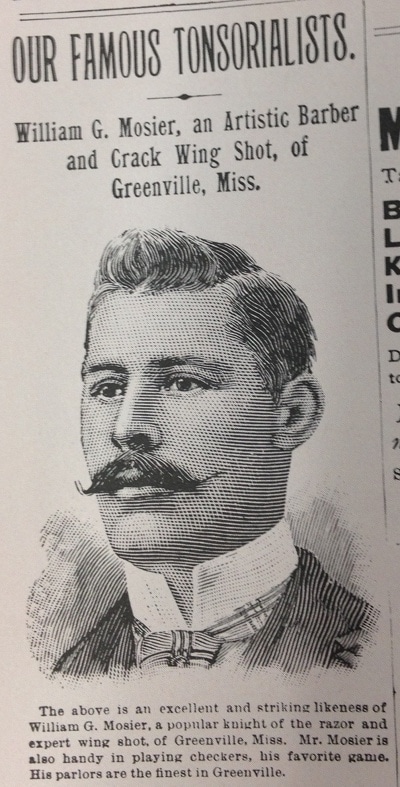

Barber of the Month

If I ever fulfill my dream of becoming a barber, my business card will say, “Brett McKay: Knight of the Razor.”

To encourage barbers to subscribe to the magazine, the Police Gazette had a section called “Tonsorialists of the Week” in which they featured barbers who subscribed to the magazine. It was great advertising for the barber. I’ve thought about starting something similar on the Art of Manliness. Anybody interested in me highlighting barbers and their barbershops once a month?

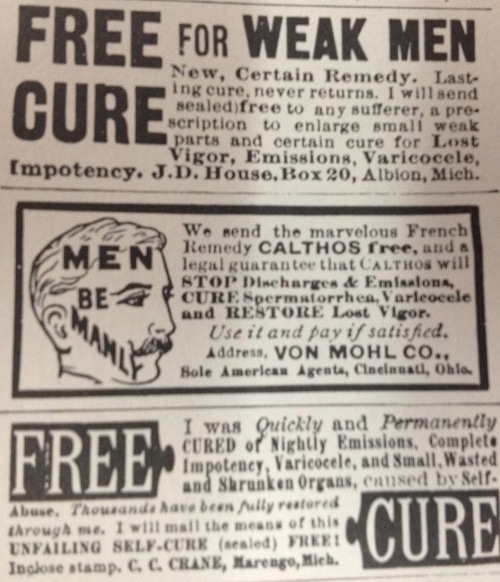

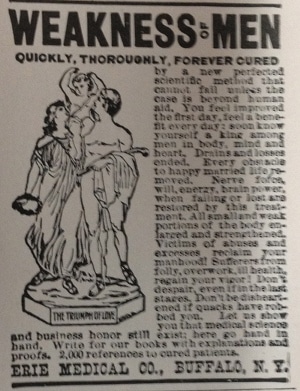

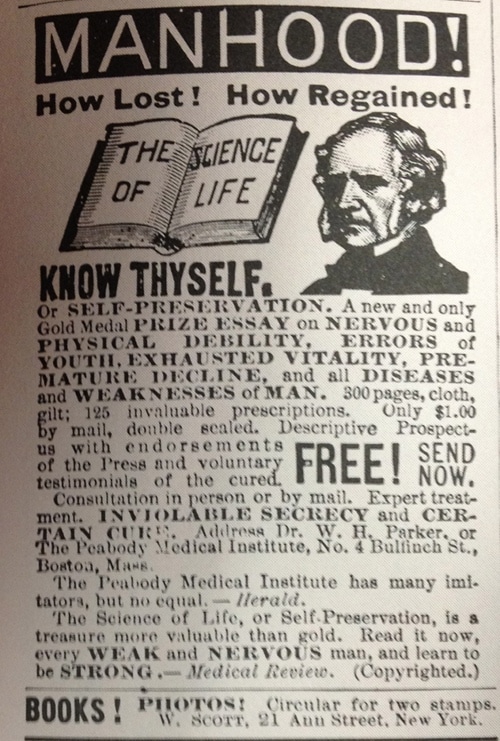

Advertisements for Cures of Your Manly Woes

Most of the revenue for the Police Gazette came from the classified section at the back of the magazine. There were lots of ads for products that promised to cure erectile disfunction, or as they called it in 1885, “lost vigor.”

You can actually read this book for free online. The gist: stop whacking off.

_________________________

Sources:

The Age of the Bachelor: Creating an American Subculture by Howard P. Chudacoff

The Gilded Age by Joel Schrock