Oftentimes when young people look back on the period of the 1940s and 50s, they see themselves as completely different than those who came of age during that time. And in many ways, they are. The rising generations hold far more progressive attitudes on issues of race, sex, gender, and more, and see themselves as quite a liberated group.

Yet in other ways, today’s teens and 20- and 30-somethings — Generations Y and Z — are in fact surprisingly like their midcentury counterparts.

Today we’ll take a look at how, and examine whether these striking parallels, and the fact that modern young people are a lot more prudish and “square” than is often appreciated, is a cause for pride, or concern.

Commonalities Between the Modern and Midcentury Generations

Morally “Clean” and Wholesome

While the popular trope is that “young people today are worse than ever,” this is decidedly not the case when it comes to common vices. Today’s younger generations are much more like the clean-living young adults of the 1950s than they are like their GenX and Baby Boomer parents.

Both Millennials (those born from ~1981-1996) and iGen’ers (~1997-TBD), are significantly less likely to smoke, drink, and have sex than previous generations.

When high school students in 1980 were asked which substances they had recently used, 30% had smoked cigarettes and 72% had consumed alcohol; today, those numbers are less than 20% and 40%, respectively. While in 1981, 43% of high school seniors had tried an illegal drug other than pot, in 2011, only 25% had done so. Just between 2008 and 2014, drug and alcohol use dropped 38% amongst teens.

According to a survey done in England, the number of young adults 16-24 who abstain from alcohol entirely rose 10% between 2005 and 2015.

At the same time, young adults are having their first sexual experience later, and having less sex in general. While in 1988, 60% of boys had had sex by the time they were 19, in 2010 that number was 42%, and overall, the number of sexually active 9th graders has dropped by almost half since the 1990s.

In iGen, professor of psychology Jean M. Twenge reports that “In fact, more young adults are not having sex at all”:

More than twice as many iGen’ers and late Millennials (those born in the 1990s) in their early twenties (16%) had not had sex at all since age 18 compared to GenX’ers at the same age (6%). A more sophisticated statistical analysis that included all adults and controlled for age and time period confirmed twice as many ‘adult virgins’ among those born in the 1990s than among those born in the 1960s. . . .

Even with age controlled, GenX’ers born in the 1970s report having an average of 10.05 sexual partners in their lifetimes, whereas Millennials and iGen’ers born in the 1990s report having sex with 5.29 partners. So Millennials and iGen’ers, the generations known for quick, casual sex, are actually having sex with fewer people—five fewer, on average.

The phenomenon of this “sex recession” has been found not only in the United States, but in other developed countries as well.

More Materially Than Existentially Minded

Members of Generations Y and Z may be dressing for work in gray cotton hoodies instead of gray flannel suits, but their desire for a stable job, and willingness to keep their head down to make good money, is remarkably like the midcentury men who once donned that corporate uniform. Similar too, is young adults’ focus on getting ahead over contemplating the deeper questions of life.

As Twenge reports, “Entering college students are more likely to say it’s important to become very well off financially (an extrinsic value), and less likely to say it’s important to develop a meaningful philosophy of life (an intrinsic value) . . . the differences are large, with 82% of 2016 students saying that ‘becoming very well off financially’ is important versus 47% saying ‘developing a meaningful philosophy of life’ is important.”

In fact, the number of college freshmen who said “being very well off financially” was important was the highest ever since the survey was begun in 1966 (a year in which only 45% of students said the same, and having a philosophy of life was rated as students’ most important value).

Comfortable With Censorship

The 1950s are often remembered for the period’s censorship movements — attempts to ban books and music that contributed to juvenile delinquency and purge public institutions of communist sympathizers.

Today’s generations, while ostensibly more open-minded, have become increasingly comfortable in advocating for the same kind of restraints on free speech — albeit in the service of very different targets. While Generations Y and Z are not concerned about things like pornography or communism, they do feel a desire to censor speech and media related to issues of race, gender, etc.

The number of stories in which college students protested a certain speaker coming to campus or called for the firing of a professor who said something deemed inappropriate are of course legion. But the evidence that young adults are less tolerant of unfettered free speech, and more sure of the idea that certain types of it can be “dangerous,” is born out in research studies as well.

While an increasing number of modern college freshmen consider themselves to be above average or better in their tolerance of different beliefs (about 80% of students rated themselves as such in 2016), about 70% believe that “colleges should prohibit racist/sexist speech on campus,” the highest number since the survey started in the 1960s. And 43% believe “colleges have the right to ban extreme speakers from campus,” a number double that registered in the 60s, 70s, and 80s.

Other studies have found similar results. As Twenge shares, “The Pew Research Center found that 40% of Millennials and iGen’ers agreed that the government should be able to prevent people from making offensive statements about minority groups, compared to only 12% of the Silent generation, 24% of Boomers, and 27% of GenX’ers. . . . More than one out of four students (28%) agreed that ‘A faculty member who, on a single occasion, says something racially insensitive in class should be fired.’”

The Strengths & Weaknesses of the Rising Generations, Mirrors of the Midcentury

To those who are only familiar with the popular narratives surrounding the rising generations, it may be surprising to find commonalities between them and those of the mid-20th century. But for those who’ve studied the Strauss-Howe generational theory, it shouldn’t come as a surprise at all.

Formulated more than 25 years ago, the theory posits that 4 generational archetypes repeat themselves in a regular pattern, and predicted that Generation Y would mirror the Greatest Generation, and that Generation Z would mirror the Silent Generation (and that both these generations would be fairly similar to each other: the Silent Generation largely followed in the footsteps of the Greatest Generation, as iGen’ers have Millennials, though there are differences; GenZ is actually even more conservative about vice, money-minded, and comfortable with censorship, than GenY). “Mirror” generations match up with each other as to where they reside in the reoccurring cycle and share characteristics that, though they can manifest themselves in very different ways, emanate from the same archetypical “personality.”

Each of the 4 generation types that make up the cycle possess a unique constellation of strengths and weaknesses that are a product of the environment/circumstances under which it came of age. A generation’s weaknesses will push the pendulum of the culture’s zeitgeist too far in one direction; the strengths of the next generation then work to restore balance and push it back the other way . . . while their own flaws plant the seeds of new problems, which successive generations have to correct for in turn.

A generation’s strengths and weaknesses are not two separate things; rather, the latter are but the shadow sides of the former.

Generations Y and Z, who came of age during the Great Recession, were reared by overprotective parents, and learned that anything they said or did could wind up on the internet forever, evince a (literal and metaphorical) sobriety, prudence, steadiness, well-adjusted friendliness, pragmatism, and flexibility that contrasts with the more passionate, idealistic, but immature and ideologically rigid dispositions of Baby Boomers, as well as the more cynical and edgy bent of GenX’ers. (We should note that the Baby Boom and GenX generations have their own strengths in comparison to these younger generations, which were partly formed in response to the weaknesses of the Greatest Generation and the Silent Generation; around and around the cycle goes.)

Much good has come from the traits of Generations Y and Z. That they started to have sex at a later age may mean that fewer young adults got into a serious relationship they weren’t mature enough to handle. The teen birthrate has fallen 67% since 1991 (by half between 2008 and 2014 alone), and the rate of drinking and driving among those ages 16-19 is down 54%. Just since 2002, there’s been an almost 40% drop in drunk driving among all young adults of legal drinking age.

Teenagers take school more seriously; 9 out of 10 think it’s important to get good grades and nearly 84% now graduate high school — a record high. And Millennials’ sober approach to finances has them saving more, including for retirement, than Baby Boomers and GenX’ers, as well as carrying less credit card debt than past generations did at their age.

Contrary to popular belief, the divorce rate has been falling, not rising, over the last 30 years; those who married in the 2000s are so far splitting up at even lower rates (especially among the college-educated, of whom only 11% have divorced), and if current trends continue, nearly two-thirds of marriages will never involve a divorce.

So Millenials’ and iGen’ers’ frugal, stable, “wholesome,” ways have wrought laudatory behaviors. As the sociologist David Finkelhor argued in an op-ed for The Washington Post, the younger generations are “showing virtues their elders lacked . . . We may look back on today’s youth as relatively virtuous, as the ones who turned the tide on impulsivity and indulgence.”

Yet as with all virtues, these traits also have their shadow sides.

The caution and prudence of Generations Y and Z can unfortunately trend into over-anxiety and timidity — and this is especially true in the case of the latter cohort.

As Twenge reports, the youngest generation is simply less comfortable taking chances:

iGen’ers’ risk aversion goes beyond their behaviors toward a general attitude of avoiding risk and danger. Eighth and 10th graders are now less likely to agree that ‘I like to test myself every now and then by doing something a little risky.’ Nearly half of teens found that appealing in the early 1990s, but by 2015 less than 40% did.

iGen teens are also less likely to agree that ‘I get a real kick out of doing things that are a little dangerous.’ As recently as 2011, the majority of teens agreed that they got a jolt out of danger, but within a few years only a minority shared this view.

After studying iGen thoroughly, Twenge concluded that “They are obsessed with safety.” This abundance of caution emerges in data points like the fact that iGen’ers are less likely to get their driver’s license by the time they graduate high school, and to physically confront someone; “In 1991, fully half of 9th graders had been in a physical fight in the last twelve months, but by 2015, only one in four had.”

But Twenge notes that iGen’ers are not just concerned about physical safety, but emotional safety as well. And this carefulness, which Millennials also evince, and which extends to avoiding any anxious, or awkward, or hurt feelings, creates a trepidation about pursuing things of real significance — paths that lead to healthy adventure, personal growth, and vital fulfillment in many of life’s domains.

Take relationships.

As Kate Julian observed in her Atlantic Monthly piece on the “sex recession,” given that sex of every type and stripe is absolutely everywhere because of the rise of digital porn, it’s ironic that young adults are not only having less of the flesh and blood variety, but are seemingly becoming more prudish about engaging in what is, of course, a highly vulnerable act. Anecdotally, she notes, young people seem to be feeling more inhibited about their naked bodies in general, and are even much more likely to change behind closed doors at the gym than older folks. We are surrounded by sex, yet our age feels strangely unsexy; we can explore sex without taboo, but don’t know how to be sensual.

As Julian further observes, the fact that young people are having less sex may bespeak not only a decline in physical intimacy, but in the kind of emotional intimacy that leads to relationships of every kind.

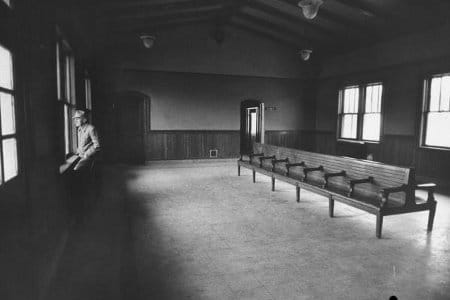

Indeed, while about the same number of iGen’ers say they want to get married and have children as Baby Boomers did at the same age, and almost ¾ of college students would like to be in a loving, committed relationship, young adults are finding it increasingly difficult to engage in the face-to-face interactions required to make these goals happen.

Twenge reports that “The number of teens who get together with their friends every day has been cut in half in just fifteen years, with especially steep declines recently,” and that “18-year-olds are now going out less often than 14-year-olds did just six years prior.”

Young adults, used to being able to mediate their social engagements through technology — which allows them to control the conversation and edit their communications — are increasingly avoiding in-person interactions, which require the riskiness, and vulnerability, of responding on the fly.

Financially, risk aversion shows up in young adults’ reluctance to start their own businesses. We popularly believe that the rising generations are more entrepreneurial than ever, and it’s true that Millennials admire start-up founders and like the idea of becoming one themselves more than previous generations. But the number of young people actually starting their own businesses has in fact gone down over the last two decades, not up. As EIG co-founder John Lettieri told the U.S. Senate Committee on Small Business and Entrepreneurship, “Millennials are on track to be the least entrepreneurial generation in history.” Young adults are increasingly putting the desire for financial security ahead of an interest in hanging out their own shingle.

Risk aversion can also manifest itself in greater conformity. The flip side of pushing for greater censorship in society, is that its silencing wind can blow back on you. Everyone becomes more fearful of accidentally making a verbal gaffe. It’s not surprising then that, as Twenge reports, “iGen’ers are more hesitant to talk in class and to ask questions—they are scared of saying the wrong thing and not as sure of their opinions. (When McGraw-Hill Education polled more than six hundred college faculty in 2017, 70% said students were less willing to ask questions and participate in class than they were five years ago.)”

Millennials and iGen’ers also show their increasing conformity in their diminishing ability to think and act creatively. Studies have shown that while IQ as well as scores on standardized tests like the SAT have gone up since the 90s, measures of nearly every aspect of creativity, including the ability to think flexibly, be playful, express emotion, daydream, generate new insights, elaborate on ideas, and deviate from mainstream patterns, has decreased over the last 25 years. Today’s young adults are smarter, and better test takers, but less original and unconventional, and more literal and narrow-minded.

The most worrisome aspect of the rising generations’ risk aversion is their desire to achieve external security at the expense of internal development. Generations Y and Z are not only much less religious than older ones, but as mentioned above, they prioritize the building of wealth over developing a philosophy of life of any kind. Young adults may be better behaved, but this “morality” seems to be driven more by fear (of messing up their lives/career prospects) than undergirded by a profound why.

That today’s young adults might feel they don’t have space and time to contemplate life’s great questions is understandable; according to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, people don’t feel they have the freedom to seek transcendence and higher levels of consciousness until their more basic needs are met, and young people, raised in uncertain times, believe they have to keep their head down and focus on practical matters to get ahead. They’re too busy competing with peers, and hustling to make a life for themselves, to look up and reflect on the greater meaning of it all.

But while it’s true that people who come of age in more stable times have the privilege of greater room for contemplation, finding existential purpose should never be thought of as a luxury. It’s an essential for human fulfillment and happiness. It’s no coincidence that at the same time that students have been de-prioritizing developing a philosophy of life, and fewer believe they are above average or better in terms of their spirituality as did in the 90s, they’ve increasingly rated themselves as lower in emotional health than students did 20 and 30 years ago, and rates of anxiety and depression have statistically risen on campuses across the country.

When many young adults look back on the 1940s and 50s, they’re apt to think, “I’m so glad not to have lived in that time. Everyone seemed so stifled, repressed, and conformist, cultivating shallow relationships, and putting on a happy facade which hid a miserable, stagnant reality. The men lived lives of quiet desperation, not seeking much more than to commute every day to a boring job and work up the corporate ladder. That’s not the kind of life I want.”

But trade taking the train to a traditional office with taking a bus to an open-plan working space (with a ping-pong table but just as long hours), reaching for a bottle of whisky in a desk drawer with grabbing a bottle of Soylent, and making the neighbors jealous by parking a new Bel-Air in the driveway with posting pictures of an exotic vacation on Instagram, and the lives of folks then and now may not be so different after all.

Embrace Your Generational Virtues; Go Your Own Way on Their Shadow Sides

Ultimately, no generation is “better” or “worse” than another. Each has unique strengths and weaknesses that propel the cycle of generations, and history, onward.

As an individual within a particular generation, you ought to lean into your generational strengths, to embrace the role of reviving those virtues which previous generations allowed to wane. But at the same time, you want to be aware of the shadow side of these virtues, and intentionally work to mitigate the way these generational weaknesses can be detrimental to your personal character and well-being.

If you’re a member of Generations Y or Z, you should feel sort of honor bound to bring back values of modesty, frugality, prudence, responsibility, diligence, and consensus building. At the same time, you ought to watch that your sense of caution does not bleed into cowardice, that your steadiness does not steal your spontaneity, that your desire for security does not squelch an appetite for risk, and that your pragmatism does not end up as an excuse to ignore life’s deeper questions.

The children of younger Millennials and of iGen’ers will become the generation that parallels those who fomented the countercultural revolution during the 1960s, and even further back, catalyzed the Second Great Awakening in the 19th century. If the generational theory holds up, this generation will one day look with disgust at our lack of inner depth and passion, and will rebel against what they see as an empty, complacent, conformist, spiritually sterile society.

That cultural shift may be fated. But you might still individually buck the trend. So that your grandchildren will think, “Grandpa sure was a man of good character, a hard worker, a go-getter . . . who also really had soul.”

__________________________________________________________

Further Resources:

- Our article on the Strauss-Howe Generational Cycle Theory

- Podcast with Neil Howe about the generational cycle theory

- Podcast with Kate Julian about the “sex recession”

- Podcast about The Coddling of the American Mind

- “How Millennials Could Be the Next Greatest Generation of Personal Finance”

- “A Cause Without Rebels — Millennials and the Changing Meaning of Cool”