Editor’s note: This is a guest post from Tony Valdes.

Welcome back to our series on Greek mythology. In the previous posts we established mythology’s core elements by examining the gods of Olympus, the creation of mankind, the mortal heroes, and the ten-year conflict of the Trojan War. In this final post, we will take the knowledge we have acquired and suggest a few practical applications that will help us achieve our goal of becoming better men.

Homer’s The Odyssey

As you will recall from the last post, Odysseus is the king of Ithaca and one of the heroes of the Trojan War. Though Achilles generally takes the spotlight in that infamous battle, you could argue that the real hero of the war is Odysseus. He is the mastermind behind the death of Paris and the Trojan Horse, both of which directly led to Greek victory.

You also might recall that Odysseus never wanted to join the war; he only leaves his wife Penelope and infant son Telemachus because he is forced to honor an oath. At the end of the war, Odysseus is eager to reunite with his family, but he has greater difficulty returning home than any other Greek. It takes him an additional ten years, resulting in a total of twenty years away from his family and his kingdom. Odysseus’ epic struggle to return to Ithaca is told by Homer in The Odyssey, which is a sort of sequel to The Illiad.

You may have read The Odyssey before, perhaps in grade school or for a classics course in college. If that’s true, then I encourage you to open it again and reexamine Homer’s account for its lessons in manliness. If you have never read The Odyssey, treat yourself to it. You can select a translation that fits your tastes – if you want the beauty and poetry of the tale, I suggest Robert Fagles’s excellent translation. If you prefer a more direct, novelized version, those are available too. Marvel Comics even published a hardback graphic novel if you want illustrations.

I’ve taught The Odyssey to high school students for five years, so I know the obstacles you’ll encounter while (re)reading Homer’s epic. Yes, it is long. Yes, there is a wealth of detail on each page. Yes, it will be more poetic than the sports section of your local newspaper – but how poetic depends on what translation you select. However, The Odyssey is worth it. What follows are a few insights you can take into your reading to make it smoother and more enjoyable. (Don’t worry – at the end of the post, there are a few other suggestions on practically applying your knowledge of Greek mythology that don’t feel quite so much like homework.)

The Narrative Structure of The Odyssey

The narrative structure that Homer used to tell his tale can be jarring if you are unprepared. The story of Odysseus would have been well-known by the time Homer crafted his definitive version, so he plunges in, fully expecting that the audience is already familiar with the hero. As with The Illiad, he begins by invoking the muse:

Sing to me of the man, Muse, the man of twists and turns

driven time and again off course, once he had plundered

the hallowed heights of Troy.

Many cities of men he saw and learned their minds,

many pains he suffered, heartsick on the open sea,

fighting to save his life and bring his comrades home.

But he could not save them from disaster, hard as he strove –

the recklessness of their own ways destroyed them all,

the blind fools, they devoured the cattle of the Sun

and the Sungod wiped from sight the day of their return.

Launch out on his story, Muse, daughter of Zeus,

start from where you will – sing for our time too.

The adventure with the Cattle of the Sun is near the end of Odysseus’ suffering abroad, yet it is one of the first things Homer tells us. It is a narrative technique called in medias res, which means to begin “in the middle of things.” As a result, the majority of Odysseus’ most famous adventures are told in a flashback sequence that spans four lengthy chapters. We also bounce between what it happening with Odysseus abroad and what is occurring with his wife Penelope and son Telemachus back in Ithaca. Additionally, there are a few abrupt transitions to the gods conversing on Olympus. If you feel lost at any point while you read, SparkNotes has an excellent breakdown of the book that you can view for free on their website.

Greek Hospitality

The Greeks’ sense of hospitality exceeds our own. There were three basic tenets that would govern your interactions with houseguests at that time. First, any person who arrived on your doorstep was to be welcomed in, regardless of who he or she was. A guest could be rich or poor, male or female, young or old, a familiar face or a total stranger. Second, the guest was to be given the privilege of staying in your home, where you would be expected to provide food and shelter. Last, the host would provide the guest with a parting gift. This gift was usually something meaningful and – by our standards – extravagant.

As you can see, the responsibilities of a host were much more than what is demanded by our contemporary culture. This helps us understand the lavish treatment of Telemachus and Odysseus during their respective travels. It also sheds light on the “villainous” behavior of a few of Odysseus’ hosts. More importantly, understanding the Greek sense of hospitality explains why the suitors, who were vying for Penelope’s affections during Odysseus’ long absence, were tolerated for so long in the palace. That being said, the suitors’ behavior was not acceptable to the Greeks; Homer’s audience would have been outraged at the thought of these brazen men exploiting a loophole in the hospitality system. It was generally understood that you were not to take advantage of a host, much like we know not to take more than one newspaper after we place our quarters in the slot.

Odysseus and Telemachus: Men Like Us

We read the biographies of great men so that we can learn from their virtues and flaws. The tales of the Greek heroes, though based largely in fiction, are no different, and none of mythology’s pantheon of mighty men are are quite so human as Odysseus and Telemachus.

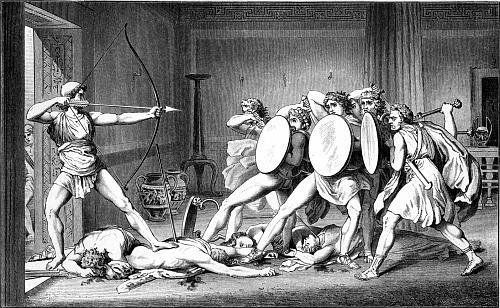

Odysseus is known for being wise and clever. He is loved and respected as a friend, husband, warrior, and king among those who know him. He displays a degree of selflessness in his concern for his men (despite their stubborn, foolish behavior). He has tenacity, perseverance, and courage that we can all learn from, and his penchant for using his brain before using his brawn is admirable. I don’t mean to imply that Odysseus lacked the ability to exert physical force – quite the contrary. When Odysseus cleanses his house of the suitors, we see how savage the fury of a man can be when he defends his family and home. This thrilling, cathartic portion of the story includes Odysseus’ eagle-eyed marksmanship, blood-soaked beard, and rippling muscles (Homer goes out of his way to highlight Odysseus’ muscular man-thighs, which always generates comments among my students).

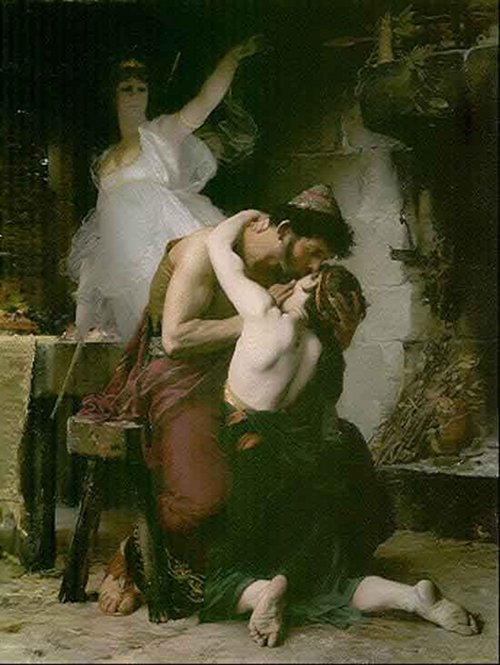

Though Odysseus clearly has a wealth of virtues, he also suffers from two common male vices: lust and pride. Though he will stop at nothing to get home to his wife and son, he is not opposed to making a detour to bed a demigoddess or two. In one instance, Odysseus is quite comfortable taking a yearlong sabbatical from his arduous journey in order to spend some “quality time” with the sorceress Circe. The double standard in the story is unavoidable: if Penelope had such a lapse, it would be utterly unforgiveable, yet Odysseus is free to sow his royal oats as he pleases.

Although Odysseus’ lust is to blame for a portion of the delay, his pride is ultimately the greatest cause. In the famous encounter with Polyphemus, the cycloptic bastard son of Poseidon, Odysseus brilliantly tricks the beast before gouging out its eye. As he sails away and mocks the creature, he shouts his name so that all might know who had victory over the muscular brute. This crescendo of pride over the humiliation of Polyphemus results in Poseidon’s relentless interference with the remainder of Odysseus’ journey.

Though Odysseus often brings problems upon himself, Telemachus is a different issue. Raised by a lonely mother, Telemachus knows of his father only through legend and rumor. As a result, he is a man-boy when we first meet him, but a hero’s blood flows in his veins and he refuses to accept his lackluster fate. Telemachus boldly leaves Ithaca on his own journey to cultivate his manhood and find his father. His is the tale of every young man’s longing to have a relationship with his dad, and become a man in his own right. Though Odysseus’ story is one of a man finding his way back, Telemachus’ is one of a man finding his way forward.

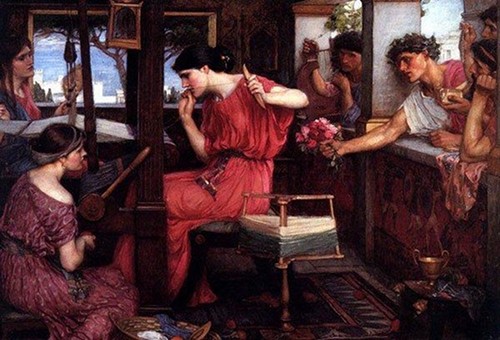

Penelope: The Woman of Our Dreams

Similar to the woman described in Proverbs 31 of the Bible, Penelope is a sample of an ideal woman. She is both beautiful and clever, and against all odds remains fiercely loyal to her husband. It might be easy to miss this because of Penelope’s circumstances in the story: we encounter her at the end of twenty long years of waiting, and she is not certain her husband is alive. Over one hundred handsome young men are clamoring for her attention, and she sometimes appears to be at her limits. Yet despite the moments where she seems ready to falter (and who can blame her?) she holds fast to her faith in Odysseus’ return. The story sets Penelope in stark contrast to the treacherous Clytemnestra, who murdered her husband Agamemnon when he returned from Troy.

The true beauty of Penelope’s character is most apparent in the final act of the story when she talks to the “beggar” (who is Odysseus in disguise) and inadvertently plays a crucial role in the suitors’ demise (though her cleverness makes me question whether or not it was truly inadvertent). The Odyssey is predominately action and adventure, but Penelope’s reunion with Odysseus and the symbolism of their great rooted bed are a love story fit for even the manliest of men.

Further Application of Greek Mythology

Reading The Odyssey and examining its characters is one of the best intersections of mythology and modern manhood that I can imagine. After reading it, you will begin to notice its influences in the most peculiar places. Try listening to “Carry On My Wayward Son” by Kansas, reading the poem “Ithaca” by C.P. Cavafy, or watching the film O Brother Where Art Thou? – you will find whole new levels of meaning in each. But, allusions to The Odyssey are few by comparison to those you’ll find about other mythological stories. Below are some other places you can exercise your knowledge.

Art Museums

If you are fortunate enough to have a local museum of art, I encourage you to go and look for the influence of mythology. Scenes from mythology have been depicted by artists throughout history because of the archetypal nature of its characters and stories. There are often travelling displays of actual Greek sculpture and pottery that you can keep an eye out for, too. Should you ever find yourself in Paris, be sure to visit The Louvre, which has one of the greatest collections of art inspired by Greek mythology that I have ever had the privilege to view (not to mention a wealth of other incredible work worth your time).

Literature

You might be surprised how often your knowledge of Greek mythology will add new depth to your understanding of literature. You’ll find references in everything from the classics (such as Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein) to contemporary young adult literature (such as the overt example of the Percy Jackson series).

Films and Television

Many Hollywood films, such as Clash of the Titans, Immortals, and Disney’s Hercules, attempt to recreate (and exaggerate) the Greek tales. Others employ more subtlety, such as James Cameron’s recent film Prometheus. Even Joss Whedon (now famous for directing The Avengers) utilized mythological references in his short-lived sci-fi television series Firefly.

Concluding Thoughts

The influence of Greek mythology is all around us. I’ve listed only a few areas here, but its echoes can be heard in nearly every arena of our lives. Listening for it can add new layers of depth to the things you encounter and can enrich your life. The heroes it presents us can be instructive in both their strengths and their weaknesses.

If you find mythology particularly interesting, I must again recommend Edith Hamilton’s Mythology, Thomas Bulfinch’s Mythology, and Robin Waterfield’s The Greek Myths. If you are interested in the broader concept of mythology throughout history, then I recommend Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces.

So by all means, explore beyond the limited boundaries I restricted myself to here. Soak up all that you can and reap the rewards of your study. You’ll not only receive lessons in manliness and a healthy dose of classical education, but you might also find opportunities to share your enriched understanding of art and literature with your significant other on an out-of-the-ordinary date night.

Primer on Greek Mythology Series:

The Gods and Goddesses

The Mortal World and Its Heroes

The Trojan War

The Odyssey and Applying What We’ve Learned

![A drawing of a group of men wearing helmets, inspired by Greek mythology. [Part II]](https://content.artofmanliness.com/uploads/2012/10/gods.jpg)