Editor’s note: The following is an excerpted chapter from Influencing Human Behavior (1925) by H. A. Overstreet. It has been condensed from the original.

The person who can capture and hold attention is the person who can effectively influence human behavior. What, we may ask, is a failure in life? Obviously, it is a person without influence; one to whom no one attends: the inventor who can persuade no one of the value of his device; the merchant who cannot attract enough customers into his store; the teacher whose pupils whistle or stamp or play tricks while he tries to capture their attention; the poet who writes reams of verse which no one will accept.

The Kinetic Technique

How, now, does one capture attention? There are a number of basic considerations. In the first place, suppose one tries to hold one’s attention immovably to a dot on the wall. It is quite impossible. The eyes insist upon wandering. In fact, if the attention is held for very long, there is every likelihood that one will induce in oneself a state of hypnosis. One will, in short, have put his waking, variously attending mind to sleep.

There must, in other words, be movement if we are to hold attention for very long. Hence, if one wishes to capture and hold another person’s attention, he must be sure that what he offers by way of stimulus moves. We might call this the kinetic requirement–perhaps the most fundamental of all requirements.

One walks down the street and comes upon a crowd gathered at a shop window. One may take a safe wager that something is happening there. Doubtless it is all of a piece with the primitive curiosity in us which responds instantly to a change of condition–the rustling of a leaf, the dropping of a twig. “What is happening?” or “What is going to happen?” If one can stir either of these questions in the minds of people–students or prospective customers, or voters, etc.–he has in so far captured their attention.

It is for this reason that a story almost invariably holds us. The story obviously moves. Something is happening; and we wish to know the outcome. Nor is the story just rambling movement–unless it is a poor story. It is movement towards. It carries us along–to something.

The Chase Technique

It is not, let us repeat, mere movement which captures and holds attention. It is dramatic movement. It is movement towards something; but also, it is movement which cannot in all its details be predicted. The movement which can be infallibly predicted soon bores us. In front of one of the dance halls in New York is an electric figure of a man and woman doing their dance steps. The movements are alway the same. The light snaps on and snaps off in precisely identical ways. Only a moron could continue to stare fascinated at that sign.

Unpredictability, then, is one of the chief ingredients of attractiveness–in story, essay, drama, in human beings. We know, of course, that the human being whose every act can be foretold–the wife who infallibly uses the same phrases; the husband who, with exact precision, tells the same stories–is a bore. Success of personality consists at least–if we may so phrase it–in “keeping people guessing.”

Listen to the dull speaker. Does he keep his audience wondering? Or do they not already see the tiresome path he has laid out for himself, along which he will dutifully tread? Or, even if they do not know the long path he will take, has he aroused them even to wish to know how and to what end he will proceed?

We have the impulse of the hunt deeply in us. We love to be after a quarry. He who presents an idea, therefore, had best present it as a quarry if he wishes to capture his audience. Just to hand out the idea is too mild a procedure. Therein lies the weakness of many a lecturer. He tells things, one after the other. After a while, the surfeited audience goes to sleep. He does not get them chasing after ideas.

Much of the weakness of our educational methods lies in the absence of the “chase” technique. Students are assigned so much to learn. They learn, but under protest and with wandering minds. The more progressive schools now increasingly utilize the “chase” technique. The student is induced to run down a quarry, either by himself or with a group of his fellows. A lesson, then, is not something to be learned. It is something to be captured. Where such a method is employed, there is no difficulty about securing the attention of the students. We may take the Dalton method as an example, where a week’s assignment is given to each child, and where the child is permitted to take up the work in any order or manner he pleases. I once asked one small English girl how she liked the method. “It’s fine,” she said. “You can figger things out for yourself when you’re on your own.” The chase! As one sits among those children, one sees no lack of attention. There is, indeed, a concentration that is wholly thrilling!

Like Begets Like

But it is not enough to get attention. A rowdy can do that. What kind of attention do we wish to attract? Our minds are like vibrating strings. If the A string on my violin is set to vibrating, it will set A vibrations going in my piano. If one comes to an audience with gloom on his face, one can hardly expect to arouse much pleasant anticipation.

Like begets like. It is most important, therefore, that the person who wishes to influence others should ask himself in what ways he is unconsciously influencing them himself–by his appearance, by his voice, his manner, his attitude. For we influence very largely in ways far more subtle than we suspect. We shake hands; and instantly we are condemned. Too limp! We speak with a raspy, querulous voice; and our auditor is all on edge to get us out of the room. We make a timid approach; and we arouse the bristling egoism of our listener. We proceed with a frank, cheerful manner; and we get frank cheerfulness in return.

There is nothing, apparently, that parents and teachers need more deeply to hear. Parents and teachers have this advantage over business men: their prospects are completely at their mercy. If the parents had to win their children; if they were in danger of losing their custom, we should doubtless have a vast improvement in our homes in the tone of voice and manners used towards our children. There are no places on this earth where more wretched techniques are used for influencing human behavior. And since, “as the twig is bent, so the tree grows,” there is a large indictment to be placed against the home.

But so, also, is the indictment to be placed against the school. Querulous, raspy teachers, irritable, domineering, unjust–they bring out in children those qualities with which our social life can most easily dispense.

We capture attention, then, by what we are. What kind of attention do we wish to capture? Interest, frank approval, enthusiasm? Then there must be in us the qualities that elicit these responses.

We might call this the homeogenic technique. If we wish one kind of attention, and get another, it is probably due to the fact that we have given no thought to those qualities in us which subtly awaken in our audience the very responses–the unfortunate responses–which are akin to our own manner and attitude.

Yes-Response Technique

The canvasser rings the doorbell. The door is opened by a suspicious lady-of-the-house. The canvasser lifts his hat. “Would you like to buy an illustrated History of the World?” he asks. “No!” And the door slams.

House to house canvassing is perhaps the lowest estate to which man can fall; nevertheless in the above there is a psychological lesson. A “No” response is a most difficult handicap to overcome. When a person has said “No,” all his pride of personality demands that he remain consistent with himself. He may later feel that the “No” was ill-advised; nevertheless, there is his precious pride to consider! Once having said a thing, he must stick to it.

Hence it is of the very greatest importance that we start a person in the affirmative direction. A wiser canvasser rings the doorbell. An equally suspicious lady-of-the-house opens. The canvasser lifts his hat. “This is Mrs. Armstrong?”

Scowling–“Yes.”

“I understand, Mrs. Armstrong, that you have several children in school.”

Suspiciously–“Yes.”

“That always requires a good deal of work with reference books, doesn’t it–hunting things up, and so on? And of course we don’t want our children running out to the library every night . . . better for them to have all these materials at home.” Etc., etc.

We do not guarantee the sale. But that second canvasser is destined to go far! He has captured the secret of getting, at the outset, a number of “yes-responses.” He has thereby set the psychological processes of his listener moving in the affirmative direction. It is like the movement of a billiard ball. Propel it in one direction and it takes some force to deflect it; far more force to send it back in the opposite direction.

The psychological patterns here are quite clear. When a person says “No” and really means it, he is doing far more than saying a word of two letters. His entire organism–glandular, nervous, muscular–gathers itself together into a condition of rejection. There is, usually in minute but sometimes in observable degree, a physical withdrawal, or readiness for withdrawal. The whole muscular system, in short, set itself on guard against acceptance. Where, on the contrary, a person says “Yes,” none of the withdrawing activities take place. The organism is in a forward-moving, accepting, open attitude. Hence the more “Yesses” we can, at the very outset, induce, the more likely we are to succeed in capturing the attention for our ultimate proposal.

It is a very simple technique–this Yes-Response. And yet how much neglected! It often seems as if people get a sense of their own importance by antagonizing at the outset. The radical comes into a conference with his conservative brethren; and immediately he must make them furious! What, as a matter of fact, is the good of it? If he simply does it in order to get some pleasure out of it for himself, he may be pardoned. But if he expects to achieve something, he is only psychologically stupid.

Get a student to say “No” at the beginning, or a customer, child, husband, or wife, and it takes the wisdom and the patience of angels to transform that bristling negative into an affirmative.

Putting-It-Up-To-You Technique

Our chief object in capturing attention, as we have indicated, is to “start something going” in the listener or beholder. Here is a pamphlet on “Habit Training for Children.” It asks questions: “Does your child fuss about his food?” “Is your child jealous?” “Does your child have temper tantrums?” Suppose these questions had been put in the form of positive statements: “Many children fuss about their food.” “Many children are jealous.” “Many children have temper tantrums.” How mild and uninteresting!

But does your child have temper tantrums? Ah, that is different! Here is something aimed directly at you. You are asked a question. You are expected to reply. Does your child have temper tantrums? Why it surely does. What about it?

And so you ask a question in turn. You have therefore been induced to do two things–to answer a question and to ask one.

The trouble with the expository method is that the sense of superiority is all on the side of the expositor. It is he who is telling. Now, let the expositor ask you a question–not for quizzing’s sake, but because he is interested to know your answer. The implication is that you can answer it. The situation is therefore reversed. It is you, now, who are momentarily superior. The speaker is deferring to you.

In the expository method, therefore, the movement is altogether in one direction–from speaker to listener. The listener therefore is merely receptive. In the putting-it-up-to-you method, the movement is in both directions. Both speaker and listener are active and receptive.

To refer again to the Dalton method of teaching, the spirit is essentially that of putting-it-up-to-you. “Can you manage your own time, or must we manage it for you?” The old fashioned expository method says: “This is what we are telling you. At nine o’clock you do arithmetic; at nine-thirty, grammar.”

The Magic of the New

Little need be said about the very real effectiveness of having something to offer that is new. The new psychology, the new education, new schools, the latest styles, the newest plays. To indicate at once that what one is offering is not antiquated, or out-of-date, or already-well-known is to have at the start a strong hold on the attention. And yet, what is offered can easily be too new. Our understanding and acceptance of anything is conditioned by what we already have in our consciousness. Introduce something that has no connection whatever with our past experience and we are not interested. The psychological rule is that there must be a large ingredient of the familiar in the unfamiliar.

The wise proponent of a new idea will make sure that the new is sufficiently tied to the old to be at least interesting as well as acceptable.

Of course, the new may disappoint us. Not every flower is born to blush in pride. The exultantly new may have its day and cease to be. Nevertheless–granting that we are fairly critical in our appraisals–it is all to the good to keep a sharp lookout for what is new–new to our children, new to our wedded mates, new to our customers and our audiences. There is magic in the new that never grows old–until the new itself grows old!

Respect the Attention Limits

Here is a small grocer. He is industrious, honest, painstaking; but one suspects he will never be anything but a small grocer. There are a number of reasons why. The most obvious is this: his windows and store are plastered over with all manner of signs. Special sales of this; so much dozen for this; best brand of that. The grocer has not learned the most elementary principle of the art of business, that to capture the public one must draw their attention to a focus.

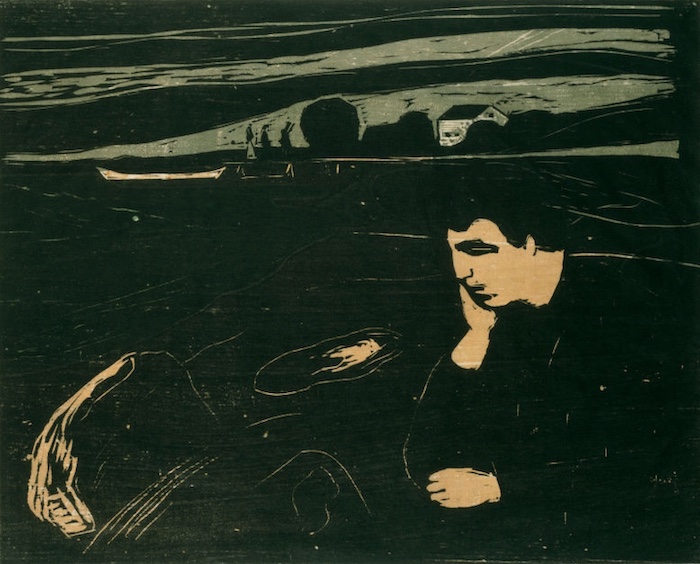

The artist–whether pictorial or musical or dramatic–knows that. A picture cannot have just a variety of beautiful things in it. It must capture the eye and lead it infallibly to one spot. There must, in short, be a dominant element in the composition.

Offer the attention too much, and it gets nothing, as the following fable indicates:

The Monkey and the Nuts

A monkey (Aesop speaking) tried to take a handful of nuts from a small-necked jar, but he grabbed too large a handful and couldn’t get his hand out, nor did he until he dropped some of the nuts.

The attempt to grab too much of the public’s attention often makes a monkey out of what might make a good advertisement.

A layout is made of a simple, strong, effective page. But the president wants another display line, the production manager wants the trademark larger, the secretary wants the package in, the sales manager wants a paragraph addressed to dealers, the advertising manager thinks the slogan should go at the top of the ad, the treasurer insists on smaller space, and the branch managers want the addresses of all the branches.

A good handful.

Only the neck of the jar is exactly as large as the public’s interest–and no larger.

To get your hand out, to get the public to look at and absorb any of the advertisement, you must drop a few nuts.

Watch People

With that admonition–“Respect the attention limits”–we close this chapter, lest we ourselves overstep the very rules we have laid down for others.

It will be a worthwhile enterprise for the reader to take the suggestions developed above and watch in how far they are observed in lectures, sermons, writings, parental admonitions, pedagogical techniques, selling methods, etc. It is rather important that one accustom oneself to this kind of psychological observation. It is almost better than observing oneself. For one can be at least drastically honest about the weaknesses of others!

Observing, then, a lecturer, writer, teacher, salesman, one might ask: Does the presentation move? Do I feel that I am being carried along? Am I being lulled into somnolence because nothing, apparently, is happening? (Kinetic Technique)

Is it moving towards something? Is my expectation keenly aroused? Am I all on “tenterhooks” to know what the outcome is to be? Or do I already see the end in the beginning? Has the whole story been given away? Is there a great deal of repetition; or an aimless going around in circles? (The Chase Technique)

Am I strongly irritated by something in the manner or attitude of the speaker or writer or salesman? Does his own lack of enthusiasm strike me cold? Does his boastfulness rouse my antagonism? Is he limp? Is he insincere? (Homeogenic Technique)

Is the first response evoked a negative one? Am I being rubbed the wrong way? Or is the person first winning my approval, leading me through successive affirmations to an ultimate agreement with his main point? (Yes-Response Technique)

Is there anything new in this sermon or speech or writing? Is it so new that I cannot make head nor tail of it? Or is the new cleverly linked on with what I already know and approve? (Novelty Technique)

Am I being deluged with facts? Do my ears buzz with endless details? Do I feel like a lost babe in the woods? Or does one dominant point stand out so clearly that I shall not forget it? (Respect-the-Attention-Limits)

Look for these simple matters of technique. There are revelations in store for the alert observer!