You may have heard of Roger Bannister and his amazing feat of breaking the 4-minute mile mark in 1954. But the story leading up to this milestone of human performance often gets overlooked and is filled with drama and lessons on grit, determination, and a living a balanced life.

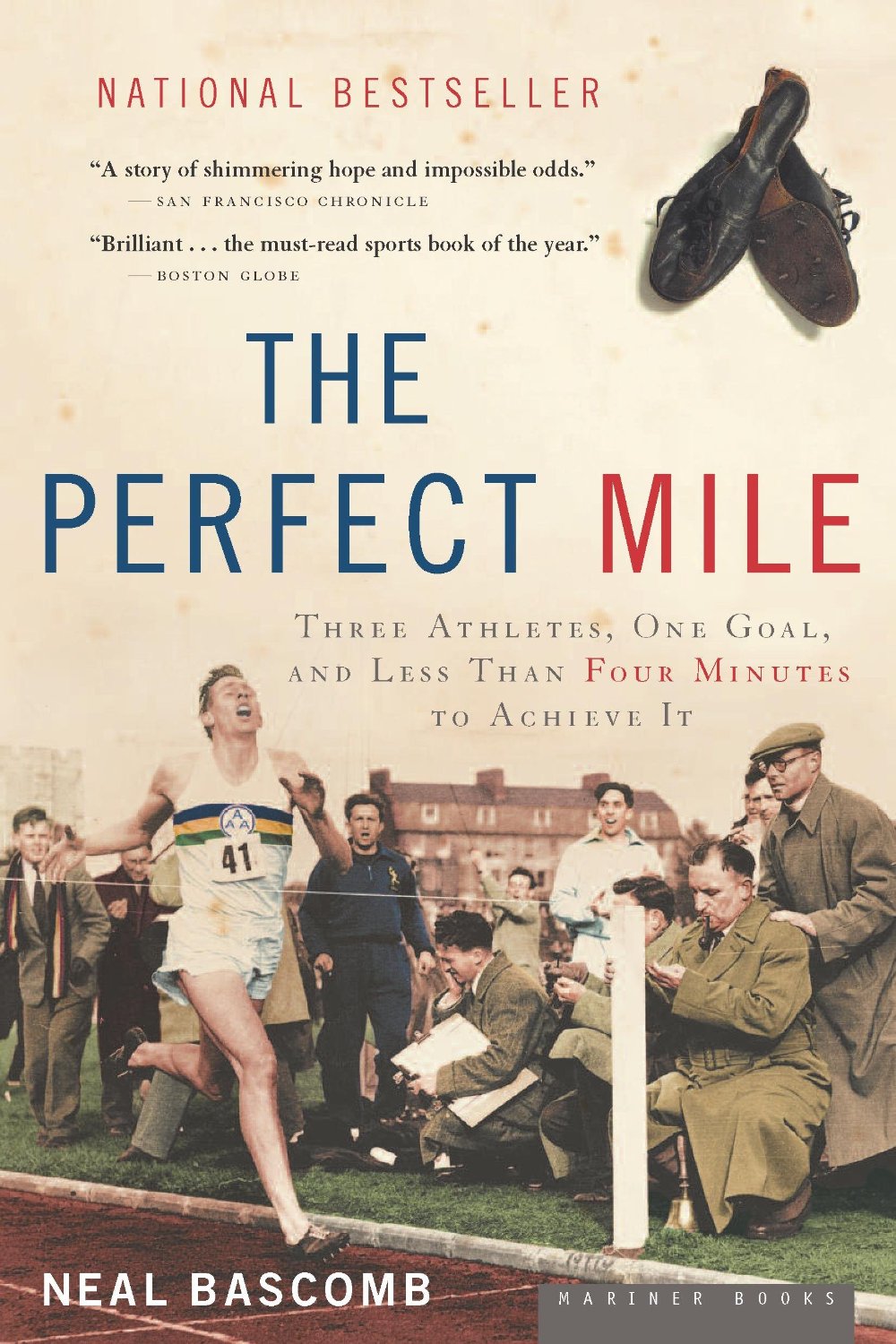

My guest today wrote a book sharing the story behind Bannister’s record and the two other men who were also vying to break it. His name is Neal Bascomb and his book is The Perfect Mile: Three Athletes, One Goal, and Less than Four Minutes to Achieve It. We begin our discussion talking about the lead up to the race in which the 4-minute-mile barrier was broken and how many doctors in the early 20th century believed achieving this milestone was physiologically impossible. Neal then tells us about the lives of the three men racing to be the first to run a sub-4-minute mile, and shares insights from them on the way the ethos of sports has changed as it’s transformed from an amateur pursuit to a professional job, as well as the ability of people to push the limits of the human body by sheer mental will.

Show Highlights

- Neal’s experience running and how he came to write about the race to break the 4-minute mile

- How long had people been trying to break the 4-minute mile?

- Why the mile is such a prestigious race

- Why didn’t physicians believe that breaking the 4-minute barrier was possible?

- How running as a sport was different in the early 20th century than it is now

- Being an amateur sportsman and adventurer in this time period

- The other men — besides the famed Roger Bannister — vying to win this race

- Bannister’s philosophy toward running and athletics

- The early sports science that went into this race

- The asterisk on Bannister’s record

- How big of a cultural event was the race to beat the 4-minute mile?

- What did these runners do after they stopped running competitively?

- What’s the record for the mile right now? Is there a threshold like 4 minutes that people are seeking?

- Did Neal learn anything about the good life from studying these athletes?

Resources/People/Articles Mentioned in Podcast

- Wes Santee

- 1,500M run at the 1952 Helsinki Olympics

- John Landy

- The History of American’s Physical Culture

- Podcast: How Bad Do You Want It?

- Podcast: The Sports Gene

- Podcast: The Myths and Truths of Distance Running

- NealBascomb.com

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Podcast Sponsors

The Strenuous Life. The Strenuous Life is a platform for those who wish to revolt against our age of ease, comfort, and existential weightlessness. It is a base of operations for those who are dissatisfied with the status quo and want to connect with the real world through the acquisition of skills that increase their sense of autonomy and mastery. Sign up for email updates, and be the first to know when the next enrollment opens up in March.

Proper Cloth. Stop wearing shirts that don’t fit. Start looking your best with a custom fitted shirt. Go to propercloth.com/MANLINESS, and enter gift code MANLINESS to save $20 on your first shirt.

Bespoke Post. Discover something cool every single month with unique themed subscription boxes. Use promo code “manliness” to get 20% off your first box.

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Recorded with ClearCast.io.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Welcome to another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. Now, you may have heard of Roger Bannister and his amazing feat of breaking the four-minute mile marker back in 1954, but the story leading up to this milestone of human performance often gets overlooked and is filled with drama and lessons on grit, determination, and a living a balanced life.

My guest today wrote a book sharing the story behind Bannister’s record and the two other men who were also vying to break it. His name is Neal Bascomb and his book is The Perfect Mile: Three Athletes, One Goal, and Less than Four Minutes to Achieve It. We begin our discussion talking about the lead up to the race in which the four-minute mile barrier was broken and how many doctors in the early 20th century believed achieving this milestone was physiologically impossible.

Neal then tells us about the lives of the three men racing to be the first to run a sub four-minute mile, and shares insights surrounding on the way the ethos of sports changed as it transformed from an amateur pursuit to a professional job, as well as the ability of people to push the limits of the human body by sheer mental will.

Really great show. After the show’s over, check out the show notes at aom.is/perfectmile.

Neal Bascomb, welcome to the show.

Neal Bascomb: Thank you for having me.

Brett McKay: You spent a lot of your career writing books about war, specifically World War II, and your book the Perfect Mile, you take a look at the epic race to break the four-minute mile. I’m curious, what led you to write about the story. Was there some World War II connection there or was it just an interest of yours that you had?

Neal Bascomb: No, actually Perfect Mile was the second book that I ever wrote that actually before I started writing about war and my inspiration for it was basically from high school. I was the high school cross-country runner and my coach suggested to all these runners really, not really a suggestion, ordered us to read Bannister’s memoir the Four-Minute Mile, Roger Bannister’s memoir. I was absolutely blown away by it. It gave me added impetus to run and to try to push myself.

Later as I started my writing career, I look back to that story and saw that no one had really done a history of really the whole story about the breaking of the four-minute mile. That it was more than just Roger Bannister’s story, but it was the story about three men all in their early 20s trying to achieve this landmark record.

Brett McKay: Before you do these three men, let’s talk about the backstory of this, of the four-minute mile record. How long had people been trying to break a four-minute mile before these three guys started doing it in gusto in the 1950s?

Neal Bascomb: Well, it dates quite a bit actually. I mean as early as 1770, a runner said that he had run the four-minute mile down London’s old street. There was no official record of that and it’s very likely a myth. Probably in the late 1800s, the mile and this idea of achieving a four-minute mile really came to fore. There was what was called at that time the mile of the century by two brothers who were competing against each at other in West London and they got the record down to four minutes and 18 seconds.

Then as the 20th century hit, you find that the tracks are improving, stopwatches are improving as well, and this idea of running four laps, four quarter miles in four minutes, the perfect balance of that really captivated people and runners began chipping away towards the four-minute mile. Paavo Nurmi, the Finnish runner, got it down to 4:10. In 1937, Sydney Wooderson got it down to 4:06 and then two Suedes in the World War II years knocked that down to basically four minutes and one second.

Then that’s where it stood and people thought or believed in many ways that four minutes was an achievement that simply was impossible.

Brett McKay: Yeah, you had physiologists chiming in on this. What did they think would happen if a man did run a minute or run a mile under four minutes?

Neal Bascomb: Yeah. I’d say physiologists, probably the good ones, would not go to the hyperbole that many went to, but my book opens up with the statement that men thought that people would die if they ever attempted to reach four minutes. That the heart, that the lungs simply didn’t have the capacity for it. There was this barrier both I think physiologically but probably more psychologically that it was an impossible achievement.

Brett McKay: Why is the four-minute mile such a hard feat? What makes it different from, say, an 800-meter sprint or a 5k?

Neal Bascomb: Well, I think the mile and milers say this, but I think track coaches and many people who are intimately involved in the running world consider the mile, the perfect combination, perfect balance between speed and endurance. You need both of those to become an expert miler. If you’re a marathoner, endurance is what you need for most. If you’re a sprinter doing a 100-yard dash, speed is what you need most. If you’re going to run a mile under four minutes, you need to both be able to sustain incredible amounts of speed over a fair amount of distance.

If you ever try, in fact, to come close to what a four-minute mile is I would just running on a treadmill and knocking it down the speed until you’re as fast as you can go and that’s probably about a five-minute mile and your legs are just going like crazy. You can imagine what improving that speed by 20%, 25% is about.

Brett McKay: How are people training for this before these three characters you followed in the book started really gunning for it? Were they scientific about it or were they just like just run as hard as I can until I can’t anymore?

Neal Bascomb: I think the training at this time was not particularly advanced. I think the big training movement that really ramped up speed subsequent to these events are two a day training sessions. At this point in time people weren’t using coaches really that much. They were running once a day. They were doing limited intervals and they were basically, in some respects, just running long distances and hoping that that would improve their times.

There was a runner named Emil Zátopek who at this period of time was beginning to train in a more modern way but Bannister and these others who were raising to break the four-minute mile when they started they were really training under rudimentary methods at best.

Brett McKay: Right. What I also love about this book besides telling the story of these characters is how you describe what sport was like during this time in early part of the 20th century, particularly running. How was it different than from what it is today?

Neal Bascomb: Well, I think the fundamental difference is this idea of the amateur athlete, the ethos of that, the idea that at this time that, again, coaches were scoring, running and competition and athletics was about fun and about the effortlessness of it. There’s this anecdote which I love particularly. There was an Oxford sprinter, a guy named Bevil Rudd and just to give you an idea of what people considered an athlete should be or how they should approach their sport. He was a sprinter. He arrives at a quarter mile race with a cigar chomping in his mouth. He put it down on the side of the track. He ran his sprint, he won, he picked up the still smoking cigar, stuck it back in his mouth and sauntered away from the track.

That is an extreme example of what the amateur effortless athletic runner was about, but it gives you an idea of the world these people were living in at the time.

Brett McKay: It wasn’t like today where like you have athletes who dedicate 24/7 to train for their sport like the amateur athletes strive to have a well-balanced life and sport which is one of many things they did.

Neal Bascomb: Yeah, sport was one of many things. It was not a career. It was not something that they endeavored to make money off of. They thought that they would run in their early 20s and then they would go off and pursue a career. Often, they were studying at the same time and there just was no expectation that this was more than just an intense hobby.

Brett McKay: Then this was particularly a British ethos, correct, like United Kingdom?

Neal Bascomb: Yeah. I mean I would say this. The British exemplified this the best. I think the Americans in typical American fashion were exceeding and professionalizing what running and athletics was but even in the United States, one of the principal characters in the story, Wes Santee, was bedeviled by this, I think, evolving world between amateur athletics and what sport was to become, which was professional athletics.

It’s one of the reasons, again, I wrote this book. I just felt it was this particularly nice moment in sport where the last of the great amateur athletes achieves a landmark record. I think subsequent to that, that world slipped away from us.

Brett McKay: Also, it was interesting, this is going on, the race for the sub four-minute mile was going on at the same time when this other amateur idea of the amateur adventurer. We had people trying to scale Mount Everest and doing all these other epic things. It was catching that same vein and it was the last of the amateur adventurers as well.

Neal Bascomb: Yeah. It was this Sir Edmund Hillary who was in the … I hate to use this word but I will, the milieu of Roger Bannister and these others, the men who considers themselves adventurers, explorers, pushing boats not only the personal records but also great achievements.

Brett McKay: Let’s talk about these characters specifically. Everyone probably knows Roger Bannister so we’ll save him for last. Let’s talk about, you mentioned Wes Santee. There were three individuals, Wes Santee was one of them, he was an American but tell us more about his background and how he approached breaking the sub four-minute mile.

Neal Bascomb: Wes Santee was the American, one of the three in the story all trying to achieve the four-minute mile at the same time. He was from a small town Kansas farm, an awful guy who beat Wes pretty terribly whenever he tried to perform his sport growing up. His father wanted him to work the farm, he didn’t want him to be interested in athletics or anything like that, didn’t want him to run. Running for Wes Santee was his way out of that world away from the farm.

He was recruited to the University of Kansas by the great track coach there, Bill Easton, and became very quickly the greatest miler in America by great strides. Wes was quite a bit of a character. He was very brash. He loved the glamour, loved the press, he was considered the “Dizzy Dean of the Cinders.” He would approach the track, he would say I’m going to run this time like Babe Ruth’s pointing to the sands where he’s going to hit the homerun and then he’d run that exact time.

He was competing both for the university and then also trying to achieve the Olympics in 1952. I think one of the foundations of the story is that all three of these individuals competing for this, Roger Bannister, Wes Santee, and then John Landy all had approached the ’52 Helsinki Olympics hoping and believing that they would win or at least place in the medal and none of them did. By the end of that Olympics, they were rearing to go to try to prove themselves and the mile was the way that they were going to do that. Breaking the four-minute mile was in some ways redemption for all three of these runners.

For Wes who was still competing for the University of Kansas and was running races almost on a weekly basis, not only running the mile but even longer distances, he was just constantly, constantly running, running, running, running and competing, competing. Though he was shooting for the four-minute mile, he also had the responsibilities of so many other things. That’s in very stark contrast to the two other runners, Bannister and Landy, who were much more focused on simply breaking the four-minute mile. That was their ambition. That was the focus of all their efforts. In some ways Santee was handicapped by the constant running and constant racing as opposed to the two others.

Brett McKay: You mentioned earlier that Santee was bedeviled by this transition from amateur athletics to the professionalization of the sport. I mean how did that play out in his life and in his running career? Any examples of that?

Neal Bascomb: It did not play out well for Wes Santee. I mean Wes was and I met and interviewed all three of these gentlemen over the course of writing the book. Even in his 70s, Wes was still heartbroken over what happened to him in this period of time. Basically, amateur athletics in the United States, a lot of people were making money except for the athletes themselves. You can almost draw a line to what’s happening in college athletics, college football and the like where you have this world in many ways exploiting these athletes.

Wes who was not a shy individual pushed up against that and was offered travel money basically to go to different events across the country. Because he was so brash, because he was so in your face I think the athletic community in the US was intimated or afraid or in some ways wanted to knock him down off that stool. They essentially did that over the course of the 1954 and ultimately, ended up banning him from racing right at the crux or the most important moments of breaking the four-minute mile where he didn’t end up getting his chance.

Brett McKay: Then, the organization you’re talking about here is the AAU, correct?

Neal Bascomb: Correct.

Brett McKay: Correct. You mentioned earlier so I’m guessing Santee never broke the four-minute mile, correct?

Neal Bascomb: Santee never broke the four-minute mile. He came within 30 seconds of it but that was the closest he ever got. I think a combination of overrunning, overcompeting coupled with the AAU controversy, which eventually forced him out of the sport kept him from achieving it.

Brett McKay: What did he do after his running career was over?

Neal Bascomb: After his running career he ended up selling insurance across Kansas and then made a career of that, raised a family. Again, when I met him in Kansas in 2002, I believe, I mean he still talked very emotional about his father. In some ways he was still a bit of an open wound about what happened to him about the four-minute mile and the AAU expulsion.

Brett McKay: Let’s move over to John Landy. He was an Australian runner. How did being a runner from Australia disadvantaged him or maybe how did that disadvantage perhaps give him an edge as well?

Neal Bascomb: Well, I think that that disadvantage for Landy at least in Australia was the lack of focus on running, the running culture there. Growing up running and competing in athletics was not necessarily something that a young Melbourne boy would aspire to be. Landy came from middle class background, nice family, he loved to chase butterflies. He came to running late in his life or late in his teens but found that he had this amazing, at this period, ability to push himself to compete out of almost sheer will.

He was eventually recruited to join a band of merry runners as I look at it led by this guru I guess is the best way of explaining him or he was a bit of freak but he knew running very well, a man named Percy Cerutty. He was a short guy who’s about five foot two, Cerutty, and he ran barefoot, he ran around town in Melbourne shirtless wearing his very small shorts and recruited Landy and a bunch of other runners to train them to be the best. He had these outlandish methods. Not only was running barefoot part of that but running up and down sand dunes, running through nature, living off a vegetarian root-based diet, considered running a, best way of saying it, as an art, as an expression of art.

Landy thrived under that for a while because it was fun and it was something where he found himself on a team and was pushing and getting better and better. Ultimately, Cerutty did not believe that will or running more and more was the way to achieve and to get better. Landy, at a certain point, decided that he could train himself and he could push himself harder and longer than anybody else.

You have Landy, I think of all three runners probably the one who trained the most, who trained the hardest, was running hours and hours at night after school and really ground himself down and pushed himself. Probably, I’d say was the best conditioned runner of the three of these challengers to the four-minute mile.

Brett McKay: Yeah. When I was reading about Landy’s coach, he reminded me the Paleo movement that you see today.

Neal Bascomb: Exactly, yes. Imagine that in 1954. That was not the rigor.

Brett McKay: You mentioned Landy, after he broke, he got more intense with his training. Did his style of running change after he broke from his coach that allowed him to give him an edge in his running?

Neal Bascomb: No, I wouldn’t say his style of running changed dramatically. I mean his stride changed a little bit. The barefoot running helped augment that but for Landy, it was really about putting in the miles about keeping a notebook and writing, “Okay. Today I went eight miles in the morning. I did this speed. Tomorrow I’m going to do nine miles” and then just ramping that up all on his own without any great interval training or scientific methods about it, just sheer putting on the miles to improve.

It did wonders. He became the greatest Australian miler at the time and steadily chipped down at the four-minute mile and got very close to being the first person to break it.

Brett McKay: Also, you mentioned that he … while he didn’t have a coach, he did look at how some of the other runners were training. I guess he took a lot of inspiration from those finished guys that were doing really well in the Olympics.

Neal Bascomb: He did, particularly, from Zátopek who we met at Helsinki Olympics and took away some of those interval training methods. Again, all sort of notes, no rigorous schedule that we have today where you know you’re going to do two minutes hard burst and then 15 seconds off and at this heart rate and at this level of effort. It just he was experimenting by feel more than anything else.

Brett McKay: Let’s move to Bannister. He’s from England. What was his philosophy towards running and athletics in general?

Neal Bascomb: Yeah. I think Bannister was the archetypal amateur athlete. He was a conservative guy, he was quiet, he was cerebral, he was born in Harrow, England, loved running from a very early age. I think one of his crystalline memories is running on a beach as a child and that freedom of movement. He writes beautifully about that in his memoir about running. I think above and beyond anything else, a love of running. I think what you had in Bannister was just an absolute killer in terms of competitive will. I mean, meeting him years ago, the intensity of his eyes, the intensity with which he spoke of these races almost 50 years later was absolutely remarkable.

Bannister is the amateur athlete. Although he wanted to be the best, he also wanted to pursue his career. At this time of the training, he was training to break the four-minute mile, he was studying to become a doctor. He was interning at Saint Mary’s Hospital. He attended Oxford. He was achieving this excellence in medicine to become a neurologist while at the same time, trying to break this record. He had very little time to do that. He was training at lunchtime at best to half hour walking to the track near the hospital and putting in his time and then going back and seeing patients.

He was, again, the supreme example of the amateur athlete, at least at the beginning of this story .That subsequently evolved as he got closer and closer to four minutes.

Brett McKay: Yeah. You mentioned Landy. His training was experimentation, trial and error, but Bannister with his medical background, he got scientific with how to best approach breaking the four-minute mile and he researched. I guess he developed his contraption to test VO2 max, correct?

Neal Bascomb: Yeah. He was testing VO2 max. He was testing lactic acid in his muscles. He had built this treadmill in the lab at school and he would put himself on that thing and hook himself up and run as fast as he could and then hop off and take blood samples and then do it again. Really trying to see from a scientific level what was possible, what was physiologically possible and how to push himself to a higher level. He experimented on his friends, Chris Brasher and Chris Chataway and other people. He was running a scientific experiment in some ways on the four-minute mile. I think for a period of time, that overwhelmed him in the sense that he was approaching this from a purely mental level.

I think again as the story evolved, he had to embrace that love of running, which I think Santee probably exemplified more than anybody else, and that will that John Landy exemplified probably more than anybody else. Bannister, in many ways, needs to combine those will, love of running in this mental breakdown of what was absolutely necessary to break four minutes.

Brett McKay: What was also interesting about Bannister, he started off like Landy … Well, no, he started off training by himself but unlike Landy who later started off with a coach but then broke off by himself. Bannister, as he got closer and closer to breaking the four-minute mile, he actually got a coach and started working with other people to help him do this. Then he realized he couldn’t do it by himself.

Neal Bascomb: Yeah. I mean, I think that’s probably, that was the significant moment for Bannister. You have 1952, the Helsinki Olympics, the failure there. Bannister particularly was slated to win a medal. He comes back and all through 1953, he’s running on his own and getting slightly better but not to the level that he needs to. Finally, his friends, Chris Chataway, Chris Brasher and a coach Franz Stampfl, who again was beginning to pursue running in a much more rigorous new methods, new interval training in the life and really getting Bannister to push himself past the point where he thought we would break. I think that was what Stampfl did as a coach for Bannister. I think Bannister wasn’t well and he pushed himself to that point. Stampfl was the one who got him there.

Brett McKay: Let’s talk about the race in which Bannister finally beat the four-minute mile. When did that happen and was he expected to do that? He thought he was going to do it that day or were there hemming and hawing before then?

Neal Bascomb: I think it was a little bit of both. Bannister, again, unlike Santee was racing time and time again to break four minutes. Bannister took a much more measured approach to it and decided that if he was going to achieve this, he would have to pick a date, pick a time where he was at the absolute supreme level of his conditioning. Also, to do that race with pacers, with people, again his friends, Chataway and Brasher who were both runners to in some ways push him along the track as pacers to bring him to the level where he could push past four minutes.

To say that better, Bannister took this as a team approach. He knew he couldn’t do it alone on the track by himself. He needed someone to chase after and to push himself. He organized this race on May 6th 1954 in Iffley Road track at Oxford, a track that he knew very well and his two pacers would go out before him and he would follow them around and then ultimately, leave them behind the great four minutes.

Brett McKay: It’s funny you said that, you mentioned this in the book, that the fact that he used pacers put a metaphorical asterisk next to his achievement.

Neal Bascomb: No, I definitely think it did in some ways. At least in many people’s eyes the fact that he did not compete in a race and do it, that he had people pushing and in some ways he’s drafting off of them around the track did not make it legitimate. My point of view on that is that’s bullocks. He ran four minutes, no one have ever done it. He did it on the track. He didn’t have some special shoes or extreme gusty winds at his back on a straight. He ran around the track on a dim, dark day and managed it and achieved something that was remarkable. I don’t that that was the end of the story.

The reason that my book is called The Perfect Mile is because I don’t consider the breaking of the four-minute mile at Iffley Road on May 6th to be Bannister’s ultimate achievement. I think it was beating four minutes at a race against the best in the world, which he did subsequent to that.

Brett McKay: Right. The best in the world was John Landy who broke the four-minute mile after Bannister. How long after Bannister broke the four-minute mile did Landy break it?

Neal Bascomb: Landy broke it on June 21st 1954. Roughly six and a half weeks after Bannister did it. It’s interesting because Landy who had come the closest prior to Bannister had essentially given up in some ways. He had told the press that he felt like he had hit a brick wall. That there was no faster that he could go. Yet, after Bannister broke it I think in many ways a psychological barrier was broken. Landy in Finland at a race not only broke four minutes but beat Bannister’s time by almost a minute and a half, almost a second and a half which is remarkable.

Brett McKay: Landy breaks it. Santee is out because he has to join the Marines and that ended his career. You’ve talked about this, The Perfect Mile, this race, the showdown between Bannister and Landy. How big of a cultural event was this at the time? Did it captivate world audiences?

Neal Bascomb: The four-minute mile itself, this race that Bannister started off by announcing that he was going to break four minutes and this battle between Bannister, Landy and Santee captivated the world then. It brought a tremendous amount of front page news attention not only to the mile but to athletics. Once Bannister broke it again, worldwide headline news, then suddenly in August of 1954 you have Bannister and Landy, the two men in the world who had broken four minutes now facing off against each other in a race.

That just drew the attention of sports writers and newspapers and radiobroadcasters and the like. It was an international event that drew a tremendous amount of attention and in some ways, as again as I write in the book, that was the beginning of this evolution from amateur to professional athletics. This idea, this level of attention, this media presence of the commonwealth games for this epic race in August in Vancouver between Bannister and Landy.

Brett McKay: Going into the race, who was favored to win it? Was it Landy because he’d broke the four-minute mile while actually racing or was Bannister favored?

Neal Bascomb: I think that largely depends on what newspaper you’re reading. If you’re reading the London Press, they were sure Bannister was going to win. If you’re reading the Melbourne Press, the alternate would be the case. From my perspective at least Landy was the faster runner. He was suffering a little bit from a cold in Vancouver but he had been competing over the course of the story. He had more experience in some ways on that level. He was clearly in better shape and in many ways I thought a faster runner.

If I could draw back in time and look at this without knowing what was going to happen, I probably would have bet on Landy. He was the kind of runner who always went off like a jack rabbit from the start and kept and maintained the lead throughout the race. That was the kind of runner he was and he just ran away with race after race. Compared to Bannister, who in some ways was still not training at the level anywhere near what Landy was doing and had been beaten by a second and a half in terms of time. That’s pretty dramatic difference.

Brett McKay: What made the race more dramatic too, people at the time didn’t know this, that Landy before the race stepped on some flash bulb from a photographer and it sliced his foot open before the race.

Neal Bascomb: Yeah. He had a cold and had this injury on his foot but speaking to Landy about it and maybe he was just being a gentleman many years later, he said that that had no significant impact at all on his running that day. I think that’s probably the case. I think pure adrenalin would have obviated that injury although it was in some ways serious. His foot was blood soaked at the end of the race.

Brett McKay: What allowed Bannister to win? He just dug deep and just tapped through that will, that competitive killer instinct to win in that final kick?

Neal Bascomb: I think it absolutely was about Bannister and his killer instincts. It drew back to what I said earlier about him. He was a killer. He was a competitive monster. He needed to win, he had to win. He was very smart about it. He’d let Landy lead off, he’d let Landy in some ways expire himself a little bit and then out of sheer will and killer instinct, he drew himself closer and closer to Landy as they went into the final stretch of the race. I think most famously, and there’s even a statue of this in Vancouver, Landy looked over his shoulder to see where Bannister was knowing very well that he was coming up close on his heels and that split second of turning and that loss of momentum in his legs was the exact moment that Bannister put on his final kick. It was more than enough to not only beat Landy but also to break the four-minute mile again.

Brett McKay: What did Landy and Bannister do after this perfect race? How did they spend the rest of their careers?

Neal Bascomb: Bannister largely abandoned running subsequent to the empire games. He retired. He went on to become what he always wanted to be, a neurologist, a quite successful one, and was practicing medicine for decades afterwards and was a fairly well-renowned neurologist.

Landy, actually ran in the subsequent Olympics. Did not do terribly well but his probably most famous incident after this four-minute mile episode was when he at the Olympics stopped to rescue or to help another runner on the track and then went on to win the race even after the delay of helping another runner get up and back to his feet. Landy was very much a beloved figure in Australia. He became a businessman and then when he retired, he eventually ended up becoming the governor of Victoria, a ceremonial post, the head of state of that particular area of Australia.

Brett McKay: Yeah. It sounds like a lot of these, they moved on with their life, it sounds like.

Neal Bascomb: Yeah. I think the only one who didn’t move on with his life was Wes Santee. When I met him, he was at that time serving as kind of a … his best way to put it is a condolence mourner at a funeral parlor, which is a sad place to spend your days. Again, he constantly spoke of what happened in the four-minute mile with a great deal of regret.

Brett McKay: What’s the record for the mile now and what’s the threshold that everyone’s gunning for now?

Neal Bascomb: The record for the mile now is three minutes, 43 seconds and some change, I think, owned by a Moroccan, El Guerrouj. He’s held that record since 1999. No one chipped away at it since then. I think in some ways, the mile isn’t quite what it used to be. I think the metric system has somewhat taken dominance in the 1500-meter race which is the Olympic race is really what middle distance runners are running now and aiming to achieve. The mile has lost some of the glamour that it had in those days in 1954.

Brett McKay: Are there people still gunning for it though? Like are the people like, “I’m a miler,” that’s what they say they are?

Neal Bascomb: Yeah. I think, particularly in America, probably there’s more of this idea of being a miler and breaking four minutes which in some ways is now the standard to become a competitive miler is to actually break four minutes but actually, chip it down to 3:40 or 3:30, no one’s comes close.

I think most of the attention right now is, on running at least and at least breaking barriers, is that two-hour marathon.

Brett McKay: After writing about these three men, did you take away any lessons from them on living a good life? Do you think they should serve as models for athletes today?

Neal Bascomb: I think it’s probably impossible for this idea of the most elite athletes in the world to be pure amateurs. I think that day is lost but I think, at least from my perspective, from someone who enjoys running and enjoys sport, I think, the idea of doing it for the pure sake of enjoyment is something I took away from this book. I still go on runs these days where, they’re shorter every year, where I have this moment where I’m … My most recent one was down in Mexico on an abandoned beach where I ran for miles and then into the hills.

I remember stopping and having this exalted moment where running was beauty and it was just pure and it was just for the sake of it. Not for exercise, not for anything else.

That’s something that I think Santee and Landy and Bannister all had in their own way. That’s one thing that I drew from their experiences over the course of the story. I think the other one was what it takes to achieve the impossible. This idea and this is a simplification but this idea that Santee ran from his heart throughout his life. Landy ran from pure will. Bannister approached it at a cerebral … from his head. I think that the way that Bannister was able to break four minutes first and the way that he was able to win at the Empire games was this ability to finally combine that heart, will and mind. That’s something that I see over and over in the other aspects of other histories that I write about people doing pretty remarkable things.

Brett McKay: Neal, this has been a great conversation and I really recommend people go get the book because the way you write and tell the story, you’re like on bated breath and see how things turn out, even though you know how-

Neal Bascomb: That’s very sweet of you to say.

Brett McKay: … even though you know how it’s going to turn out. You get pumped out. Where can people go to learn more about your work and your book?

Neal Bascomb: Sure. My books are available in pretty much everywhere they sell books. You can also … I love for you to come to the website, that’s www.nealbascomb.com, N-E-A-L-B-A-S-C-O-M-B dot com.

Brett McKay: Neal Bascomb, thank you so much for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Neal Bascomb: It’s been awesome. Thank you.

Brett McKay: Like I said, it was Neal Bascomb. He’s the author of the book The Perfect Mile. It’s available on amazon.com and bookstore everywhere. Also, head over to his site, nealbascomb.com, to learn more about his work. He’s written a lot of great stuff on World War II. Also check our show notes at aom.is/perfectmile where you find links to resources where you can we delve deeper into this topic.

That wraps up another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. For more manly tips and advice, make sure to check out the Art of Manliness website at artofmanliness.com. If you enjoyed the show, got something out of it, I’d appreciate if you take one minute to give us a review on iTunes or Stitcher. It helps out a lot. If you’ve done that already, thank you so much. Please consider recommending the show to a friend or family member. Word of mouth is how the show grows.

As always, thank you for your continued support. Until next time, this is Brett McKay telling you to stay manly.