As an adherent of “the strenuous life” — a believer in “bodily vigor as a method of getting that vigor of soul without which vigor of the body counts for nothing” — Theodore Roosevelt tried to get in two hours of physical activity every afternoon.

While serving as president, this exercise typically consisted of tennis matches, horseback riding, rustic cross-country walks, climbs and scrambles in then-wild Rock Creek Park, or even skinny dips in the Potomac River.

As an evangelist of strenuosity, TR encouraged friends, family, and associates to accompany him on these jaunts, and he was frequently joined by senior staff, diplomats, old friends from his time out West, and members of the military who together acted as the president’s informal panel of advisors.

A group of young Army officers who served as regular members of what was known as the “Tennis Cabinet,” often used these ambulatory meetings with Roosevelt to lament “the condition of utter physical worthlessness” which their fellow soldiers had “permitted themselves to lapse, and the very bad effect this would certainly have if ever the army were called into service.” Looking into the matter, TR was shocked to find that “Many of the older officers were so unfit physically that their condition would have excited laughter, had it not been so serious, to think that they belonged to the military arm of the Government.” The only exercise many of these soft and sedentary soldiers took each day was to walk to the streetcar that took them to and from work.

To get the military in fighting shape, Roosevelt issued a directive requiring that the officers of all branches be able to complete “a march of 50 miles, to be made in three consecutive days and in a total of 20 hours, including rests, the march on any one day to be during consecutive hours.”

Despite this being a test, TR sardonically opined, “which many a healthy middle-aged woman would be able to meet,” it still received considerable push-back from some quarters. More senior Army officers, particularly those who had spent their careers toiling at desk jobs, worked to undermine the order and petitioned Congress to have it annulled.

Yet some soldiers and sailors felt the introduction of the 50-mile march “did a very great deal of good.” Such was the opinion of one naval officer who wrote to Roosevelt to describe the salubrious effect it had on members of the military:

“It decreased by thousands of dollars the money expended on street car fare, and by a much greater sum the amount expended over the bar. It eliminated a number of the wholly unfit; it taught officers to walk; it forced them to learn the care of their feet and that of their men; and it improved their general health and was rapidly forming a taste for physical exercise.”

Many Marines, TR reported, especially “laughed at the idea of treating a 50-mile walk as over-fatiguing,” and several officers completed the trek in a single day. Naval officials, in a bit of quintessentially institutionalized logic, subsequently made the men repeat the test and carry out their marching over three days, since they hadn’t complied with the set regulations!

While Roosevelt managed to keep the standard in place during his administration, it was abandoned after he left office, and the 50-mile test thereafter fell into obscurity, waiting to be rediscovered a half century later by another zealously active president — as well as a host of challenge-hungry civilians.

The 50-Mile March Along JFK’s New Frontier

“We want a nation of participants in the vigorous life. This is not a matter which can be settled, of course, from Washington. It is really a matter which starts with each individual family.” –President John F. Kennedy, 1961

A cultural emphasis on physical fitness tends to wax and wane, rising during times of war when it becomes a clear-cut matter of life and death, and declining during times of peace, as prosperity and comforts increase, and bodily vigor seems more ancillary to leading a happy, successful life.

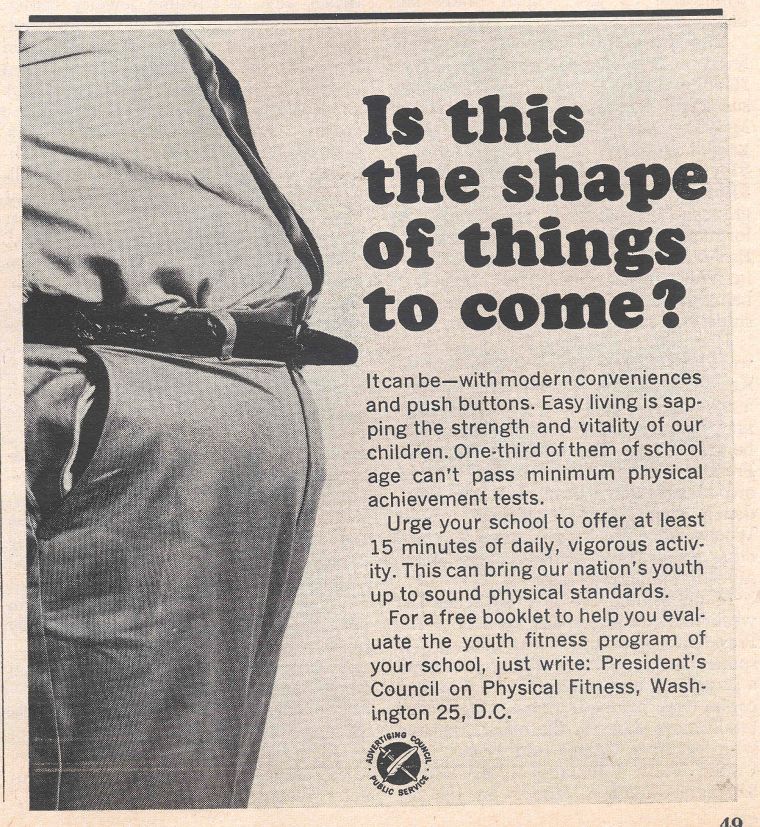

So it was that in the aftermath of WWII, as the U.S. economy soared and technological advancements made life easier and more convenient, people could seemingly afford to make physical hardihood less of a priority. Various economic and cultural factors made life in the 1950s progressively more comfortable and sedentary: new appliances lessened the difficulty of household chores; burgeoning streets and highways enhanced the viability and popularity of driving; television expanded the availability of spectator-centered entertainment. Leisure time went up, but it was increasingly spent in passive pursuits.

As welcome as many of these comforts and conveniences were, however, not all felt they were an unmitigated good.

John F. Kennedy — an adherent of the active life who played tennis and touch football, skied, swam, and skated whenever he could — worried about the complacency with which many of his countrymen had come to view their health by the early 1960s. Like the nation’s first founders, he believed that too much luxury and slothfulness — too much “softness on the part of individual citizens” — would “help to strip and destroy the vitality of a nation.” As the Cold War heated up, Kennedy believed maintaining physical vitality was key in maintaining democratic vitality.

Thus even before taking office, he determined that inspiring the country to a greater level of physical fitness would be a central aim of his presidential administration.

After the election of 1960, and before his inauguration, JFK penned a piece for Sports Illustrated entitled “The Soft American” in which he laid out a rousing call to arms as to why the country couldn’t afford to lose its vigor and dynamism and needed to treat the task of keeping in shape more seriously:

“The physical vigor of our citizens is one of America’s most precious resources. If we waste and neglect this resource, if we allow it to dwindle and grow soft then we will destroy much of our ability to meet the great and vital challenges which confront our people. We will be unable to realize our full potential as a nation.

Throughout our history we have been challenged to armed conflict by nations which sought to destroy our independence or threatened our freedom. The young men of America have risen to those occasions, giving themselves freely to the rigors and hardships of warfare. But the stamina and strength which the defense of liberty requires are not the product of a few weeks’ basic training or a month’s conditioning. These only come from bodies which have been conditioned by a lifetime of participation in sports and interest in physical activity. Our struggles against aggressors throughout our history have been won on the playgrounds and corner lots and fields of America. Thus, in a very real and immediate sense, our growing softness, our increasing lack of physical fitness, is a menace to our security.

However, we do not, like the ancient Spartans, wish to train the bodies of our youths merely to make them more effective warriors. It is our profound hope and expectation that Americans will never again have to expend their strength in armed conflict. But physical fitness is as vital to the activities of peace as to those of war, especially when our success in those activities may well determine the future of freedom in the years to come. . .

For physical fitness is not only one of the most important keys to a healthy body; it is the basis of dynamic and creative intellectual activity. The relationship between the soundness of the body and the activities of the mind is subtle and complex. Much is not yet understood. But we do know what the Greeks knew: that intelligence and skill can only function at the peak of their capacity when the body is healthy and strong; that hardy spirits and tough minds usually inhabit sound bodies.

In this sense, physical fitness is the basis of all the activities of our society. And if our bodies grow soft and inactive, if we fail to encourage physical development and prowess, we will undermine our capacity for thought, for work and for the use of those skills vital to an expanding and complex America. Thus the physical fitness of our citizens is a vital prerequisite to America’s realization of its full potential as a nation, and to the opportunity of each individual citizen to make full and fruitful use of his capacities . . .

. . . we can fully restore the physical soundness of our nation only if every American is willing to assume responsibility for his own fitness and the fitness of his children. We do not live in a regimented society where men are forced to live their lives in the interest of the state. We are, all of us, as free to direct the activities of our bodies as we are to pursue the objects of our thought. But if we are to retain this freedom, for ourselves and for generations yet to come, then we must also be willing to work for the physical toughness on which the courage and intelligence and skill of man so largely depend. All of us must consider our own responsibilities for the physical vigor of our children and of the young men and women of our community. We do not want our children to become a generation of spectators. Rather, we want each of them to be a participant in the vigorous life.”

After taking office, the young president, along with the Council on Physical Fitness, set about to fulfill his vision of getting Americans moving again. The country was blanketed with print, radio, and television advertising touting the benefits of exercise, and a fitness curriculum was rolled out to schools aimed at improving the rigor and efficacy of their recess and PE programs.

Kennedy’s most effective strategy for keying up interest in physical fitness, however, came from reviving a past president’s old challenge.

At the start of 1963, Kennedy discovered Roosevelt’s 1908 order establishing the 50-mile march for officers. He sent it to Marine Commandant David M. Shoup, noting that the leathernecks of the time had been able to complete the trek within 20 hours on a single day, and asking if “the strength and stamina of the modern Marine is at least equivalent to that of his antecedents.” If Shoup would look into that question, Kennedy promised, he would see if members of his own White House staff were up to the task as well.

Before Shoup could make plans to test his Marines, the president’s brother and the country’s Attorney General, Robert F. Kennedy, decided to jump right into the challenge himself.

On February 9th, without any training or preparation and wearing leather oxford dress shoes, RFK set out at 5 o’clock in the morning to walk 50 miles along the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal towpath. Accompanied by four of his staff members, as well as his dog Brumis, he trudged through snow, slush, and below-freezing temperatures, making his way from Great Falls, VA to Camp David, MD. Though the last of his aides dropped out at the 35-mile mark, Kennedy persisted to the end, completing the march in 17 hours and 50 minutes.

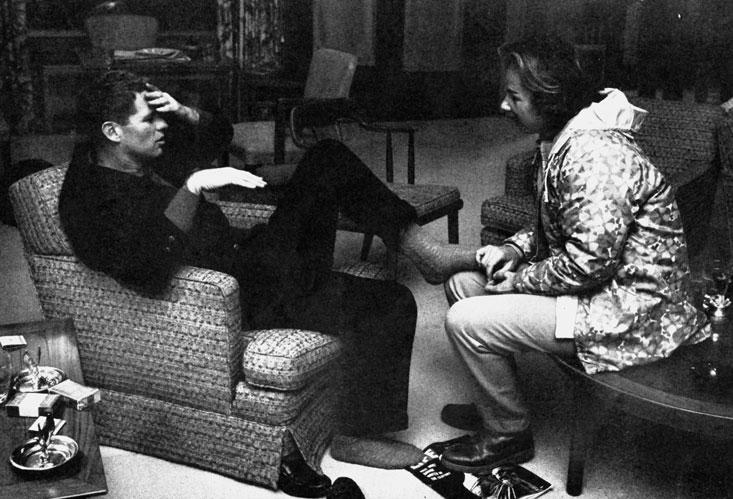

Bobby gets his tired feet rubbed by his wife after completing the walk. “I’m a little stiff,” he admitted, “but that’s natural, never having walked 50 miles before.” He bounced right back though; the next morning, Time Magazine reported, “he rose at 7:30, made it to 9 o’clock mass and then went ice skating with his children.” Photo Source: Life Magazine

The Marines were next to pick up the gauntlet the president had thrown down.

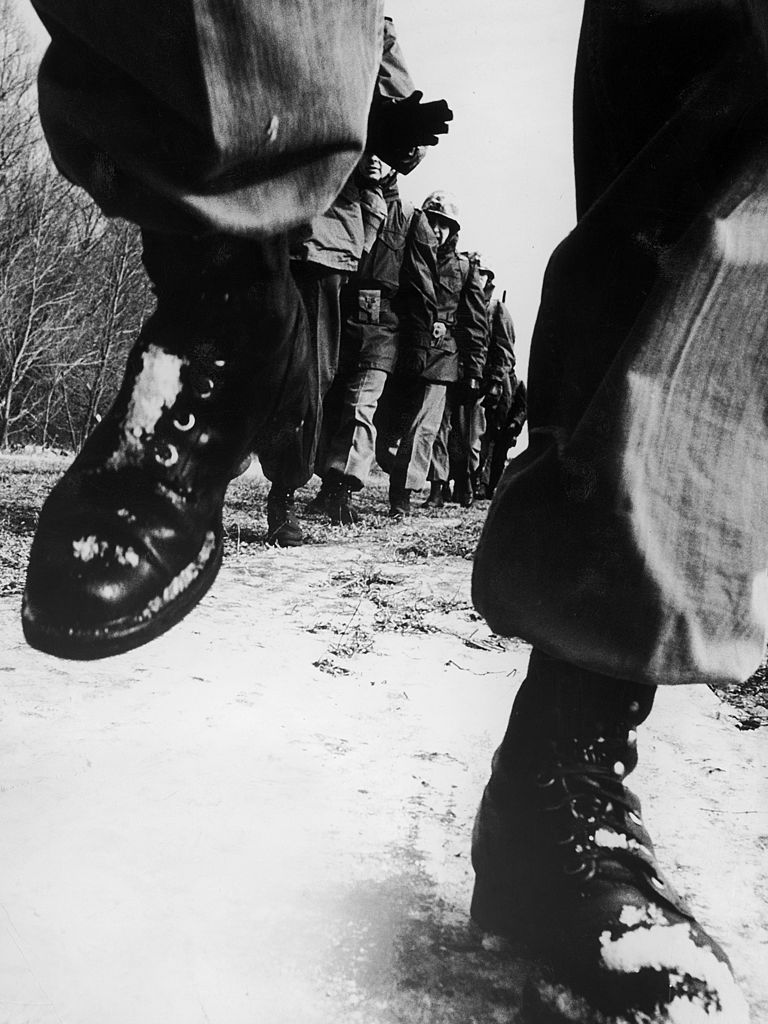

On February 12th, Shoup challenged several dozen officers of the 2nd Marine Division at Camp Lejeune, NC to march 50 miles in 20 hours. According to an article in Life Magazine, the test came as a surprise to “Some of the lieutenants and captains [who] were pulled from behind desks and told to report at the starting line at 8 am.”

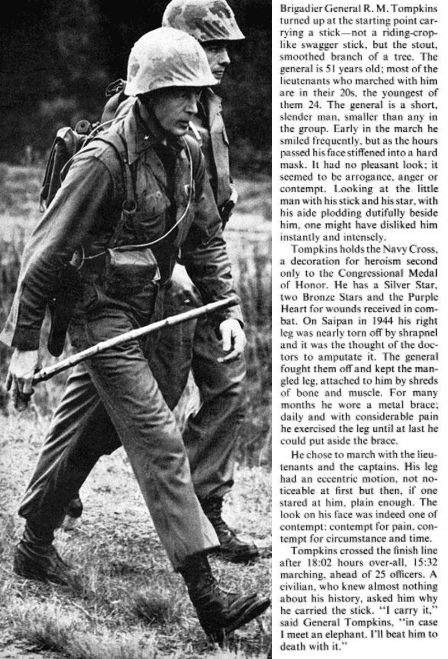

The Marines’ march was led by 51-year-old Brigadier General R. M. Tompkins, who finished 9th despite limping from an old shrapnel wound. The whole original caption from Life Magazine (above) is well worth reading for a swift kick in the pants.

The men donned helmets, pistols, and light packs, which added 25 pounds to their burden as they headed out on the long march. A second lieutenant who half walked and half ran the distance, completed the 50 miles first with a time of 9 hours and 53 minutes. The best overall all-marching time was 12:47, counting authorized breaks, with a pace of 11:44 for the time spent actually marching.

A Challenge Becomes a Craze

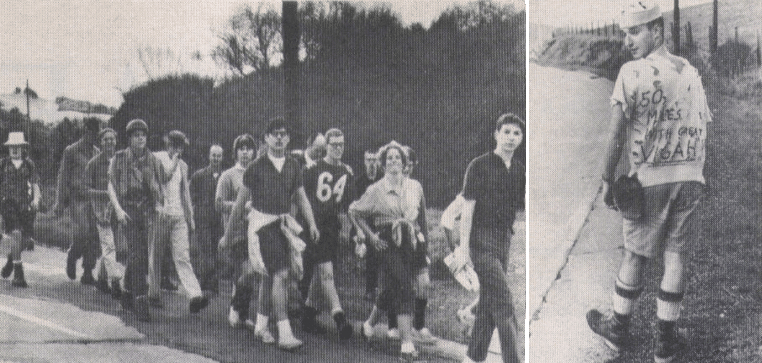

400 students from Marin County, CA attempted the 50-mile walk, but only 97 were able to complete it within 20 hours. The students marched with “Vigah!” a play on Kennedy’s Bostonian accent. Photos Source: Time Magazine

The media covered the feats of both Robert Kennedy and the Marines, and although JFK hadn’t directly challenged ordinary citizens to follow suit, and the 50-mile walk wasn’t officially sponsored by members of his fitness council (who were actually a little alarmed by the idea of rank-and-file Americans attempting such a strenuous hike), the public felt the president had thrown down the gauntlet to them as well, and were eager to take it up themselves.

Civilians across the country, hungry for a way to test their limits and slough off the sedentary malaise of mid-century life, began spontaneously braving the near-record cold of the winter of 1963, and the near-certain accumulation of blisters, corns, and aching feet, to undertake the 50-miles-in-20-hours challenge.

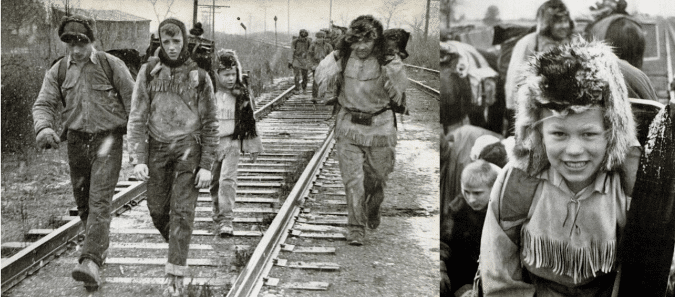

The 10-year-old 90-pound lad on the right accompanied his father and 14 teenagers on a 180-mile trek that retraced a march made by George Rogers Clark during the Revolutionary War. Though the adults caught a few rides on the three horses that accompanied them, the young man walked the entire first 50 miles on his own, finishing in 18 hours and 45 minutes, despite the fact, Life reports, “his peanut-butter-and-jelly ration froze along the way.” Photo Source: Life Magazine

50-mile walks were organized by Boy Scout troops, college fraternities, groups of military men, and a variety of youth organizations. Individuals — ranging from mailmen to reporters to politicians — set out on their own lone pilgrimages towards the half-century mark. Though many who tried the test failed to make it all the way, others turned in impressive times. A group of five 13- and 14-year-old Boy Scouts, for example, completed the trek in a speedy 13.5 hours.

Small town newspapers extensively covered locals’ attempts, publishing accounts like these (compiled by Paul Kiczek), all from Morris County, NJ’s The Daily Record, and all from February 1963:

“Cop Completes 50 Mile ‘Beat’”

Francis Wulff, 24 years old and a policeman and ex-Marine, from Somerville, NJ said, “I did it on the spur of the moment. I read about some army officers shooting off their mouths about the Marines and I decided to give it a try.”

“Ken Middleton Does 50 In 11 Hrs., 49 Minutes”

Ken Middleton, 17 years old, put in a remarkable under 12-hour time, with two other boys from the Aristocrats Athletic Club in Boonton, NJ following close behind. Five other members of their group dropped out facing temperatures as low as five below zero. Ken could only say to the press, “I’m too tired to think of anything.”

“Some Morris Countians Hike 50 Miles, Some Don’t”

Dan Wulff, 17, of Morristown and Ed DeVore, 15, of New Vernon took 12 hours and 50 minutes to go 50 miles from Morristown to Somerville. “The last 10 miles were really tough.” Dan said. “It goes to prove we are in better shape than people think we are.” Meanwhile, Richard Gardner of Randolph and his friend Thomas Ciaraffo, walked 32 miles to Newark but decided not to make the return trip by foot after noticing that the water in their canteen had frozen. Local police finally became familiar with the sight of walkers at all hours. Two Butler, NJ high schoolers were stopped after just walking 3 miles. It seemed they had neglected to get their parent’s permission.

“Summit Group Hikes to Washington’s Hdqs.”

Edward Cushing Bessy, a former Navy officer, from Summit, NJ, not particularly fond of walking, cajoled six others to join him on a 25-mile hike on Washington’s Birthday to Washington’s Headquarters in Morristown, NJ. Bessy said, “I’d like to prove that Americans haven’t grown soft and that 20th century Americans can still match the early settlers in stamina. And what better tie-in could the march have than the birthday of an American who right in this area commanded an Army composed largely of civilian soldiers.”

“Reward Offered For 50-Mile Hike”

The Mansion House Tavern, in Boonton, NJ, is offering a $25 Savings Bond to the winner of a contest called the “Fifty-Mile Endurance Walk” scheduled for March 10. Free draught beer for anyone who finishes the whole 50 miles. Already 25 participants have signed up.

“Snowstorm Fails to Halt Walkers”

Tom Dwyer, 15 years old, got caught in a snowstorm but completed a 42-mile walk in 9 hours and 30 minutes. Jack Botti, 12 and Bud Ferber 13, made it home in the same weather accomplishing 50 miles in 12 hours and 30 minutes, to break the local record set by Dan Wulff recently. Motorists stopped about 10 times to offer rides, but the boys just said, “We’re on a walking trip to break a record.”

The craze for trying the 50-mile march lasted through the spring, before slowly waning in popularity, and then almost entirely disappearing after Kennedy’s assassination that November. Though most of the president-inspired marches were canceled in the wake of his slaying, Maryland’s Buzz Sawyer, who had created one of the first — the JFK 50-Mile Challenge — committed to continuing it. Renamed the JFK 50-Mile Memorial, he put the community hike on again in 1964, and in the years that followed. Over the decades, it evolved into a running race and is today one of the premier ultramarathons in the country — as well as the last remaining event born from the year one strenuous president channeled another, and inspired a country to collectively test its mettle.

Take the JFK/TR 50-Mile Challenge

Today we live in another age in which peace and prosperity generally reigns at home, while tensions simmer around the world, and it befits every man to stay tough, fit, and ready for action.

Walking 50 miles in 20 hours is a way to test yourself, push your limits, have a bit of adventure, get reacquainted with hardihood, rediscover your physical potential, and live with vigah. I’ve committed to attempting it sometime in the next several months, and I hope you will too. If you need extra motivation, it’s one of the requirements for earning the Rough Rider Badge, part of The Strenuous Life program we’ll be launching very soon (you can sign up for updates here).

If you do decide to tackle the challenge, let us know by sharing a pic on Instagram @artofmanliness, #50milemarch.

Until we meet at the 50-mile mark, keep your shoe-leather well-worn, live strenuously, and stay manly.