This article is now available as a professionally formatted, distraction free ebook to read offline at your leisure. Click here to buy.

Words: ~7,500

Reading Time: ~45 mins

“Contest is a part of human life everywhere that human life is found. In war and in games, in work and in play, physically, intellectually, and morally, human beings match themselves with or against one another. Struggle appears inseparable from human life, and contest is a particular focus or mode of interpersonal struggle, an opposition that can be hostile but need not be, for certain kinds of contest may serve to sublimate and dissolve hostilities and to build friendship and cooperation.

Contest is one kind of adversativeness, if we understand adversativeness in the ordinary large sense of a relationship in which beings are set against or act against one another. Adversative action, action against, can be destructive, but often it is supportive. If our feet press against the surface we walk on and it does not resist the pressure, we are lost. We have all suffered from dreams in which we feel ourselves plummeting through space. Such dreams can be terrifying, for bodily existence is such that it requires some kind of againstness. Gravity is reassuring; it establishes fields where advertisativeness can work and where it functions as a central element in all physical existence.

But adversativeness is significant beyond the physical. It has provided a paradigm for understanding our own existence: in order to know myself, I must know that something else is not me and is (in some measure) set against me, psychologically as well as physically.”

–Walter J. Ong, Fighting for Life

Athenians v. Spartans

Socrates v. the Sophists

British v. Americans

Romanticists v. Neoclassicists

Tesla v. Edison

U.S. v. U.S.S.R.

Rocky v. Apollo

Hatfields v. McCoys

The State of Tennessee v. John T. Scopes

Biggie Smalls v. 2Pac

Democrats v. Republicans

Yankees v. Red Sox

Protestants v. Catholics

West v. East

Spy v. Spy

From the dawn of time, the world has been marked by conflict, struggle, and opposition. This is true in nature, where day continually butts into night; the ocean collides with the shore; and predators chase prey.

And it is true in human civilization, especially amongst its male members.

For reasons of reproduction and testosterone, men are generally more aggressive, risk-taking, and competitive than women. For thousands of years, men have engaged each other in tests of strength, skill, and cleverness in order to protect their tribe from outsiders, and to prove their manhood and gain status amongst insiders. With status came access to females and other resources, as well as glory and renown.

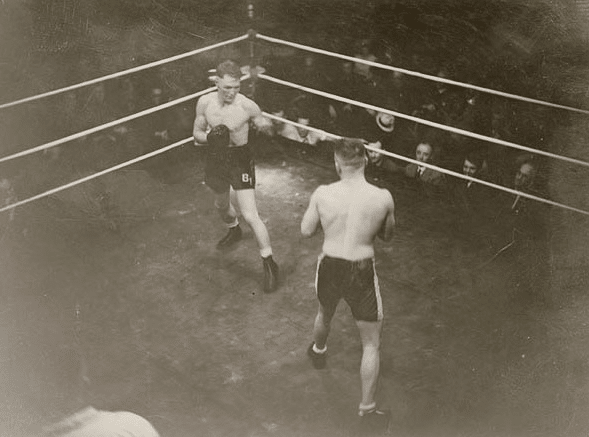

In primitive times, these contests took the form of physical brawls and battles, but for centuries they have extended into a wide array of realms: art, rhetoric, logic, politics, philosophy, science, and more. If men can compete in it, they will.

These competitions by their nature produced both winners and losers, and sometimes incurred collateral damage. But the drive of each party to be the best and rise to the top also drove societal progress; out of the sparks of collision, from the blood, sweat, and tears of contest, emerged new ideas, technologies, and ways of being in the world.

In the modern day, however, these so-called “pissing contests” between men have gotten a bad name. The male competitive drive has been blamed for wars, economic meltdowns, and political gridlock. And the entire ethos of competition increasingly finds itself at odds with the values of modern culture. Competitions are exclusive, rather than inclusive, separate people into winners and losers, and don’t distribute rewards equally. Having a keen competitive drive is seen as the purview of the domineering and insecure — while the “authentic” are above it all and operate only from self-motivation and the desire to be their very best selves.

For this reason, social commentators and policy makers have tried to figure out ways to make men more cooperative and nurturing, and have sought to remove competition from institutions like schools, believing this transformation will benefit individuals and society as a whole.

But the effort is ultimately an unwise exercise in futility. Men are hardwired to compete. And even if we could somehow kill the male competitive drive, we’d be doing a great disservice to ourselves. Male competition may carry some pitfalls for civilization, but it’s also what made civilization in the first place.

T

Part I: The Benefits of Competition

“A thing without opposition ipso facto does not exist.” –Charles Sanders Pierce

It’s true that competition is not an unalloyed good; when participants adopt a win-at-all-costs mindset and go outside the rules, they can harm their opponents, as well as society as a whole. And while competition can bring out the best in some people, its pressure can also cause others to anxiously flounder.

But competition, when engaged in by those who keep a healthy mindset and embrace fair play, can be an enormously powerful force for good and has a number of important benefits.

In Part I, we will examine each of these vitalizing benefits in turn.

Chapter 1: Competition Makes Us Better

There has been a lot of talk in the past few years about deliberate practice as the key to mastering any skill, and with good reason. Research from psychologist K. Anders Ericsson and others has shown that effortful, deliberate practice is an important element in gaining mastery in any domain.

Nevertheless, it’s just one element.

Competition is another. In fact, you might call it the original performance-enhancing drug.

The first psychologist to uncover the effect of competition on performance was Norman Triplett. Back in 1898, Triplett noticed that cyclists tended to have faster times when they were riding in the presence of another person as opposed to riding alone. To test this phenomenon in the lab, he created a “Competition Machine” — a game where you had to reel in a line of silk cord as quickly as you could.

Triplett had a group of children spin his Competition Machine two times: one time alone and one time against another competitor. Triplett’s theory about people performing better when in competition was verified: 50% of the children reeled the cord faster when faced with a competitor compared to when they were alone. About 25% of the children achieved the same time whether they were alone or competing, and another 25% had worse times when they were competing than when they were alone. (We’ll explore why some people may not be affected or perform worse during competition, and how the latter can overcome that effect later on.)

Researchers who followed Triplett built upon his initial research using more sophisticated experiments.

For example, in a 2012 study cyclists were asked several times to pedal as fast as they possibly could for 2,000 meters on a stationary bike, in order to establish their baseline “personal record.” They were then put in front of a screen that projected their avatar, along with an avatar they were told was of a competitor they were racing against, who was obscured behind a partition in the room. In fact, the “competitor” was simply an avatar set to go at the participant’s own best time.

And yet, despite the fact the participants were sure they could go no faster than they had during the trial cycles, once engaged in the heat of competition, 12 of 14 were able to beat their previous records.

In another study, recreational weightlifters were able to bench press more weight when competing against others than when practicing by themselves, and the effect was even greater when they competed in front of an audience.

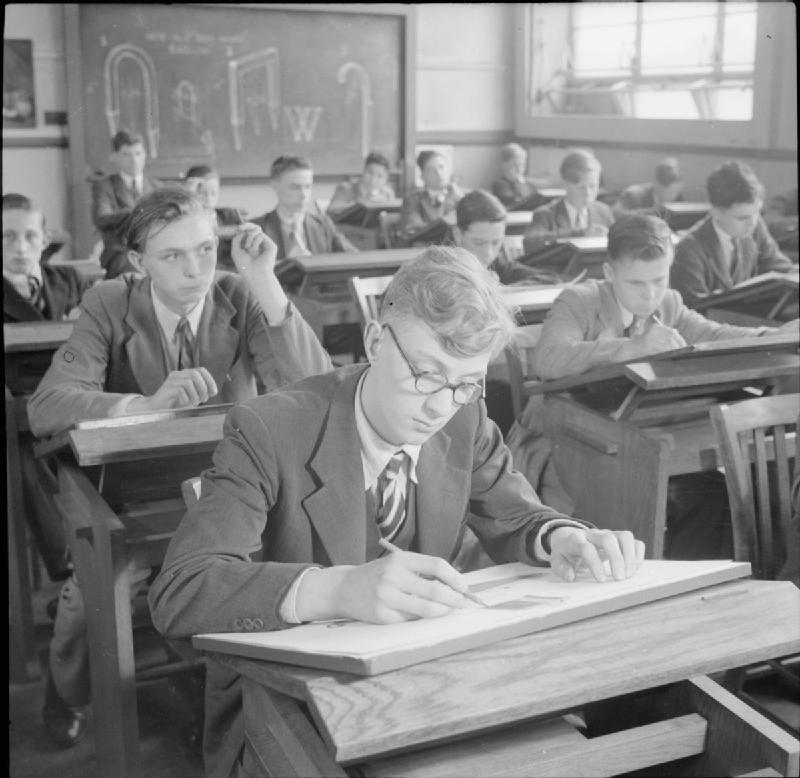

The effort-enhancing benefits of competition extend beyond the world of sport as well. Studies have shown that competition in classrooms motivates children (especially boys) to engage boring tasks, while other research has demonstrated that competitive culture in some workplaces makes employees more committed to their job, and more apt to go the extra mile in their role.

These studies that have been going on for over a century merely confirm what most of us already knew intuitively: Competition can make us better.

Why is that?

Well, the downside of competition — greater stress — is also its upside. While chronic stress is bad for your health, and over-anxiety can indeed cause you to choke, the occasional stress response, if positively embraced, can prime you for greater performance.

Knowing that we’re competing with someone sets off a cascade of hormonal and neurochemical changes in our bodies and brains that prepare us for peak performance.

Knowing that we’re competing with someone sets off a cascade of hormonal and neurochemical changes in our bodies and brains that prepare us for peak performance. Under ordinary circumstances, your brain is very stingy in releasing physiological resources; it will tell you you’re fatigued long before your body will actually become physically exhausted.

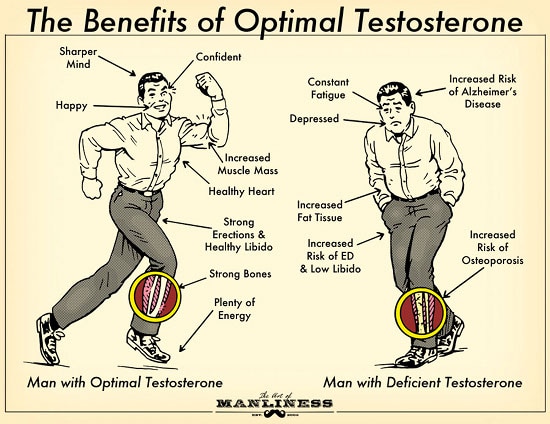

But when you’re competing, your brain goes into fight-or-flight mode and becomes more generous in doling out the physiological resources you need to face the “threat.” Your heart rate increases, your testosterone goes up (which increases your drive for success), cortisol is released (which boosts your alertness), and you feel like you have more energy to burn. Your brain also gets very motivated by its chance to increase your status, and releases dopamine, which drives you towards a reward.

These physiological, and consequently, psychological changes allow us to dig deep and push ourselves past our preconceived limits. You don’t get this effect when you’re practicing by yourself or even with your friends, because there’s nothing truly at stake.

It’s important to keep in mind that you don’t even have to win to get these benefits. During the 2008 men’s Olympic swimming relay, in which the Americans won in dramatic fashion, the four teams that lost still finished ahead of the world record time. While they didn’t win the race, they improved simply by taking part in a close, intense competition.

Besides providing a performance boost, competition also helps us improve by providing an external source to measure ourselves against. Competitors can reveal flaws and weaknesses in ourselves we didn’t know we had. If we lose, we can take that feedback back to our practice and work on it so that we can do better next time.

Thus, while people often say the best kind of competition is striving to beat ourselves, if we truly want to find another gear, we need to compete against others.

Chapter 2: Competition Fosters Cooperation & Morality

Competition and cooperation are often viewed as antithetical, and collaboration is seen as the better, more moral of the two virtues. Social commentators bemoan the male competitive drive as the source of many societal ills, claiming that it leads to cheating and harm, and arguing we’d all be better off if men acted more like women with regards to being cooperative.

But what psychological, sociological, and anthropological research shows is that, far from being the antithesis of cooperation and morality, competition can actually foster both.

First, competition requires competitors to cooperate with each other. You can’t have a basketball game unless everyone in the game knows, understands, and agrees to follow the rules. And what’s true for basketball goes for any other competitive domain. Individual businesses, and the marketplace as a whole, couldn’t operate unless people followed sets of written and unspoken rules — unless they cooperated while competing.

The cooperation that’s necessary for individuals or teams to engage in a competition also fosters a sense of morality. Most individuals want a “good game” — it’s not enjoyable to win if you cheat, and hard to lose with grace if the contest is rigged. For that reason, competition can cultivate morality as participants self-police, and explore and debate what’s right and wrong.

To watch the collaborative power of competition, just watch children get together before a game to establish the rules. I remember when I was a kid and played Capture the Flag in our neighborhood, we’d spend ten minutes going over the ground rules. No parents were involved — we did this all by ourselves. Once the rules were set, it was game on, and the competition was fierce. This collaborative element of competition is a big reason why play is so important for children.

Or take the art of roughhousing. The idea that competition can foster morality is actually one of the reasons child psychologists encourage dads to engage in rough and tumble play with their kids. When we roughhouse with our sons and daughters, they learn boundaries and the difference between right and wrong. If they start hitting hard, aiming below the belt, or becoming malicious, you can reprimand them and then show by example what’s appropriate roughhousing behavior. In this way, competition can be a way to train our moral intelligence.

Competition also fosters cooperation by requiring individuals on the same team to work with each other. Some teams do have a show-boat or a ball-hog who tries to steal the spotlight and be a one-man show. But the best teams are typically those whose members work together — individuals who are willing to unselfishly sacrifice sometimes in order to set up their teammates, and the entire team, for success. Through this kind of cooperation, teammates build tight, loyal relationships with each other.

In fact, competition is arguably the primary way males bond with one another. Anthropologist Lionel Tiger first made this observation in his seminal book Men in Groups. For Tiger, male bonding is intimately entwined with male aggression and competition. According to his research, men typically form tight bonds “in terms of either a pre-existent object of aggression, or a concocted one.” Men draw close together when they have some other group against which to compete or some difficult goal to achieve together.

Sports teams and military units are prime examples of the way in which competing with external groups/teams/challenges, bonds men together. In the military, a common refrain amongst soldiers is that while they may have gone to war to fight for their country, they stayed to fight for their brothers. Each man in a unit has to intimately cooperate and give their best in order to win the battle against the enemy, and protect the lives of their comrades. With sports competitions, though the stakes aren’t as high, men often recall their teammates as the best friends they ever had.

If society wants to develop men who look out for people other than themselves, and know how to be loyal and unselfish, it should encourage more competition, not less.

All of this is to say, that far from being antithetical to cooperation, competition can in fact breed the keenest kind of cooperation there is. It’s the catalyst for deep friendships and moral behavior. If society wants to develop men who look out for people other than themselves, and know how to be loyal and unselfish, it should encourage more competition, not less.

Now of course, there are cases where competition is so fierce, that people end up throwing cooperation out the window, trampling over others, and doing unethical things in order to get ahead. But the problem in such cases isn’t competition itself, but a culture in which honor, integrity, and fair play haven’t been inculcated. Competition doesn’t make people do immoral things; it’s a neutral tool, which, as just discussed above, can actually bring out the best in people. Competition doesn’t breed corruption, a corrupt culture breeds corrupt competition.

Chapter 3: Competition Spurs Creativity

We often imagine that the great artists from history did their art for art’s sake and that they cared little about how they stacked up against their peers.

The reality is that most of the great art we have today is thanks to intense competition.

For example, fervent competition infused the culture of the Renaissance.

Most of the great art we have today is thanks to intense competition.

First, there was competition in the bottega, or workshop, where apprentices would simultaneously cooperate on the work of their masters while viciously competing with one another to be the best. Praising the competitive environment of the bottega, Leonardo da Vinci once wrote, “You will be ashamed to be counted among draughtsmen if your work is inadequate, and this disgrace must motivate you to profitable study. Secondly, a healthy envy will stimulate you to become one of those who are praised more than yourself, for the praises of others will spur you on.”

Second, artists and their patrons competed intensely among themselves in the free market. It was common in art contracts during the Renaissance to have clauses guaranteeing that an artist would outdo another artist’s work. If the artist didn’t fulfill his contract, he didn’t get paid. For example, in one of Raphael’s contracts, he agreed to create an altarpiece that was better than a work by Perugino. He did and was rewarded handsomely for it.

Modern research has born out what these Renaissance artists experienced firsthand. For example, in one study musicians were asked to improvise music on a keyboard in both a non-competitive and competitive environment. Their improvised tunes were then judged by a panel of ten experts. Improvisers in the competitive setting did feel more stress, but they were also more intrinsically motivated about the task, and ended up producing music that was judged more creative than that which was made by those in the non-competitive condition.

Another study done at Colgate University found that judges tended to rate children’s creative work as more creative when the children had been told beforehand that their creation was for a contest compared to when they were told it was just for fun.

Granted, not all kids get this creativity boost from competition. Just as in Triplett’s experiment, some children weren’t affected by the competition, and some children performed worse, but most were more creative when they thought that they were competing with each other.

Thus while we often think that competition is the antithesis of creativity, and that real, “authentic” artists create only for themselves and are motivated solely through the muses, a little external pressure, and the ethos of contest, might be just the thing to unlock the full potential of one’s talents.

Part II: How to Get the Most Out of Competition

The bottom line from Part I is that competition begets some powerfully positive benefits, but does come with some caveats. It can spur you to go the extra mile, develop your capacity for cooperation and morality, and boost your creativity. But it doesn’t do so for everyone. For some groups, it has no, or the opposite effect. And that’s because for these folks, the pressure and stress of competition gets to them. They get nervous; they choke; they get overwhelmed and plain give up. It’s often for this reason that modern society has soured on competition; it seeks to protect those whose psyche and performance might suffer in a competitive atmosphere.

Yet removing competition to protect one set of people from potential harm, also removes the conditions under which another set would thrive and reach an even higher level of performance.

Might there be a way to mitigate the ill effects of competition for the great majority of people while harnessing its potentially positive benefits for the greatest number of folks?

Happily, there is.

How we react to the pressure of competition comes down to a mixture of nature and nurture. The chapters of Part II will offer tips which will address both these factors, and can be applied to helping you make the most of competition as an individual, as well as how to best incorporate a competitive atmosphere on an institutional level.

Chapter 4: Keep the Competition Close

Competing against others can help us summon reserves we didn’t think we had, but researchers have found that the competition has to be close in order to reap these performance-enhancing benefits. If the people you’re competing against are lapping you, you have a tendency to just give up. This effect is particularly pronounced in men.

The U.S. Air Force Academy learned this lesson a few years ago when they conducted an experiment involving the class of 2010. They had noticed that cadets with lower grades improved their grades if they socialized and spent time with cadets with higher GPAs. So they decided to see if they could reduce the first-year dropout rates of the lowest-performing incoming cadets (students with the lowest SAT and high school GPAs) in the class of 2010 by assigning them to squadrons with the highest-performing incoming cadets (students with the best SAT and GPAs). For their control, they created units that were filled exclusively with average students.

They expected to see the lowest-performing cadets start improving from rubbing shoulders with the highest-performing cadets. But that’s not what happened. The lowest-performing students started doing significantly worse. What’s more, the average students in the control group saw a dramatic improvement in their grades. What was going on?

Humans are very conscious of their status. If we’re always comparing ourselves and competing with people who are way ahead of us in some domain, we get fatigued by the constant status defeat that occurs. This is what happened in the mixed low/high Academy group. The gap between the highest-performing and lowest-performing cadets was so large that the low-performing students stopped using the high performers as a reference point for their own performance, and started self-segregating. The low-performing students started only hanging out, eating, and studying with other low-performing students as a way to protect their psyche.

But what about the squadrons of average-performing cadets? Why did they improve? Well, the competition was so close between all of them, that they had to make a lot of effort to distinguish themselves even a little from the pack. Close competition pushed the middle-of-the-pack students to up their game.

Researchers studying poor students who get accepted into prestigious charter schools through a lottery have noticed a similar trend of lower-performing students doing worse when competing and comparing themselves with much higher-performing students.

What’s more, the effect is acuter in boys than in girls.

Poor girls who are accepted into elite charter schools typically thrive. Their grades improve significantly, and their chances of attending college after graduation go up. Most boys, on the other hand, flounder. Their grades go down, and their risk of dropping out goes up.

However, when the researchers looked at the boys who had lost the charter school lottery and had to go to an easier, less academically rigorous school, they noticed that their academic performance and standardized test scores went up.

The researchers concluded that boys do better when competition and status comparisons are close. Status-conscious males have a tendency to throw in the towel if it seems impossible to win a competition. Men would rather be the big fish in a small pond, than a small fish in a big pond. Women, who are generally less status-conscious than men, aren’t affected by large discrepancies in ability or status between them and their peers.

People are made of stories, not atoms.

In other words, that motivational poster in your grade school classroom was wrong; if you aim for the moon, you won’t end up among the stars. You might not get off the ground at all.

To get the most out of competition, you have to compete with those who are similar to you in ability. Buddies, associates, and opponents who sometimes beat you, and who you sometimes beat. It pays to have a (possibly quite friendly) archnemesis. If you’re a rank novice, don’t try to compete with the high-performers right off the bat. It will just demoralize you. Have some humility, seek out folks on the same level as you are, and use them as your pacesetters. Your performance will improve little by little, and before you know it, you’ll be hanging with the big dogs.

Don’t Have Time to Finish the Rest of this eBook?

Sign up for our newsletter to get a PDF of it to read at your leisure.

Chapter 5: Compete With a Small Group

Besides competing with those with abilities similar to yours, you should make the group against which you’re competing small and ensure it stays that way.

Just as we tend to sandbag it when the gap between us and the top is huge, we reduce our efforts when the group we use as a reference to assess our performance is very large.

Researchers Garcia and Avishalom call this performance decline the N-effect. After looking at SAT scores in 2005, they noticed that students who took the test in large venues with lots of other test-takers had lower scores than students who took the test in smaller venues with fewer test-takers.

They had a hunch that students’ performance was hampered when they perceived that they were competing with a large number of people, and they tested this hypothesis in the lab. They brought in students to take a test and told them that they were competing with others to see who could finish it the fastest with the most accurate score. They told one group of students that they were competing against nine other people, and the other that they were competing against ninety-nine.

The result? The students who were told that they were competing against just nine people finished the test faster and more accurately than the students who were told they were competing against ninety-nine others.

Our brain’s competitive and status-seeking drive is primed for competition within small groups.

The reason we let up when we’re competing against a large field is likely due to evolution. Our prehistoric ancestors lived in small, tightly-knit units consisting of no more than a few hundred people. Our brain’s competitive and status-seeking drive is primed for competition within small groups. But in today’s digital world, you’re often not competing with just a few dozen others, but possibly thousands or even millions of people across the world. Our brain’s evolved competitive drive isn’t equipped to handle that, so we let off.

Understanding that we compete harder when the group we’re competing in is limited, we’d serve ourselves well in narrowing the focus of our competition so that it’s small and relevant to us. Instead of trying to have the most profitable business in the world, seek to have the most profitable business in your niche and your state. Instead of trying to compete to be the strongest dude on Instagram, try to be the strongest guy in your local gym.

Of course, as you improve, the focus of your competition will shift, but it still needs to remain small. With some hard work and a bit of luck, perhaps your small competitive field will consist of the best of the best. Focus on competing with just those guys, and don’t think about being the best in the world. It will just sap your motivation.

Chapter 6: Don't Start Competing Too Soon

As we’ll explain in Chapter 11, studies show that genetics may play a role in whether we can handle the pressure of competition or not. But our ability to shine under the spotlight can also be affected by our skill level.

Research by social psychologist Robert Zajonc has found that competition and the presence of spectators can hamper performance if you’re in the beginning stages of learning a new skill. Knowing that others are watching makes an already self-conscious beginner even more self-conscious. It’s a distraction. On the other hand, individuals who have mastered a skill improve with competition and an audience.

Zajonc theorizes that, while beginners need positive feedback (the kind you don’t get when you lose in a competition because you’re a beginner) to improve, experts benefit from the criticism and extra scrutiny competition provides. For those who are already on their way, the contest atmosphere offers needed friction to sharpen and hone their skills even more.

So if you’re just learning a new skill, don’t be in a rush to compete. The competition will just hamper your learning of said skill. Instead, practice until you’ve got the basics mastered. Once you feel comfortable with the basics, sign up for a competition or at least exhibit your skills publicly so you can further sharpen your ability. For example, if you want to improve your public speaking, sign up for Toastmasters and develop that skill in the supportive environment of the organization’s meetings. Once you’ve mastered the basics of delivering a speech, find an opportunity to speak in front of a large audience or even sign up for a speech contest to hone your skill even more.

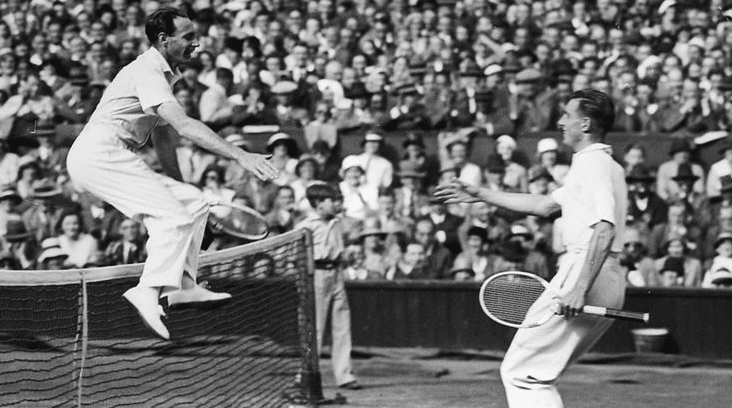

Focusing on what you stand to gain from competing as opposed to what you can lose will not only help you decide to compete in the first place, it will also help your performance once the competition is underway. Researchers have found that when tennis players during Grand Slam tournaments play to win instead of playing not to lose, they perform better. They play more aggressively, while players who play not to lose become so defensive that they don’t try to score the points they need to win a match.

So if you’re reluctant to go toe-to-toe with others, remind yourself of what you stand to gain from competing as opposed to what you have to lose, and throughout the competition, play to win and not to lose.

Chapter 7: Think About What You Have to Gain, Instead of What You Have to Lose

If you’re reluctant to take part in competitions, you’re missing out on some of the amazing benefits they offer. The reason many folks are unwilling to compete is because they’re afraid of what will happen if they lose.

One way to foster a competitive drive within yourself is to simply shift your focus from what you have to lose to what you could gain. Research shows that individuals who focus on a competition’s possible benefits, instead of its downsides, are more likely to throw their hat in the arena.

Is failure a possibility? Of course. Often the odds are stacked against you. However, if you don’t enter the competition, your chances of winning are zilch, and even if you lose, you can still win thanks to the performance-enhancing benefits of competition. You might not beat your opponents, but could very well end up surpassing your own personal performance marks.

Focusing on what you stand to gain from competing as opposed to what you can lose will not only help you decide to compete in the first place, it will also help your performance once the competition is underway. Researchers have found that when tennis players during Grand Slam tournaments play to win instead of playing not to lose, they perform better. They play more aggressively, while players who play not to lose become so defensive that they don’t try to score the points they need to win a match.

So if you’re reluctant to go toe-to-toe with others, remind yourself of what you stand to gain from competing as opposed to what you have to lose, and throughout the competition, play to win and not to lose.

Chapter 8: Get an Honor Group

As we’ve discussed many times before on the Art of Manliness, the male gang has always been the primary social unit of men. Anthropologists have found that ancestral humans formed close-bonded bands for the purposes of hunting and fighting. Even in modern, industrial societies like America, sociologists have noted that boys are more likely to run around in large groups of other boys, while girls spend most of their time in dyadic pairs.

The male gang, what I like to call a platoon, constitutes an honor group — an exclusive, tight-knit, all-male society of equals. Every member is expected to live a certain code of behavior: those who excel at the standards are honored, while those who show disdain or indifference for them are shamed, and possibly excluded.

Honor groups foster both inter- and intra-competition. Within an honor group, friends compete within one another to excel at the virtues and skills valued by the team. Because the honor group is both small and made up of roughly equal peers, the competitive fire is stoked to the max.

Failure is also buffeted in the honor group. Psychologist Joyce Benenson has spent 30 years researching the social dynamics between boys and girls. One observation that she’s made about male groups is that so long as boy or man strives to give his all in living up to the standards of the group, the group will still see him as an asset, even if he comes up short. This provides some psychological security to a man who is deeply embedded in a male group, which, counter-intuitively, encourages him to compete even more. If he’ll be considered part of the group even if he fails (contingent, of course, on him daring greatly), then he’s got nothing to lose in pushing himself in the intra-group competition.

Besides competing within themselves, male groups like to compete with other male groups. It’s a chance to test their mettle against external opponents. It’s why men prefer team sports over individual sports, while for women it’s the reverse. Team competition simulates the primordial male gang, and cements the group’s bonds. Oxytocin — the love chemical — is released in our brains when we’re competing against another team with our team. That oxytocin release causes us to fight and compete harder. We don’t want to let our fellow men down.

Thus, having a small group of male friends with similar goals is one of the best ways to harness your competitive drive and get the most from it. The competition among you as well as with other groups will push you beyond your current abilities.

Make it a goal to find your male honor group. Join a CrossFit class, start a fight club in your garage, or start up a business with some buddies. Engage in friendly competition with other men to improve each other, and after that, find opportunities to compete against other groups so that the bonds between you are knitted tighter and you can experience the extra performance boost that comes from tackling a challenge as a gang.

Chapter 9: Harness Your Challenge Response

If you’ve ever gotten butterflies before a big performance or competition, you understand the physiological “stress response” such situations can cause. Some people have such a strong stress response that it causes them to choke when they need to perform at their best.

While practice can help train your body not to overreact in the face of intense competition, you can also change your mindset to soothe pre-game jitters. Psychologist Kelly McGonigal recommends thinking about pre-competition nervousness not as performance-degrading anxiety, but as the body’s attempt to prepare itself for a challenge. Because that’s exactly what it is.

Your body is priming itself to compete and fight. Your heart begins beating faster, adrenaline starts flowing through your veins — you feel a bit on edge because your body thinks it’s getting ready to face a perceived threat. It’s what helped your caveman ancestors spring into action when facing a saber-toothed tiger. You’re not going to die in a business pitch, but it still elicits the same physiological response because there’s risk involved.

McGonigal’s research has shown that when individuals are told that pre-competition or performance nerves are a good thing — the body’s way of getting itself ready to conquer a challenge — participants relax more, and performance on stress tests improves. When they’re left thinking that something is wrong with them and that they shouldn’t be experiencing those nerves, they choke.

So, the next time your palms get sweaty, or you feel a knot in your stomach before a big competition or presentation, remind yourself that your body is just priming itself for action — it’s getting ready for success! Changing your mindset on your nerves will calm you down, and even more importantly, allow you to perform at your best.

Chapter 10: Optimize Testosterone

People with naturally high levels of testosterone have a higher competitive drive, and are more motivated to take part in competition. This is why men tend to be more competitive than women.

Dr. Jack van Honk, a psychologist at Utrecht University, has spent his career studying the effects of testosterone on performance. According to Van Honk, “testosterone is motivation. Without testosterone, there is no motivation at all. When you take some testosterone sublingually, you’re ready to go, you’re up for it, there’s no fear, no hesitation.”

Not only does testosterone spur us to get into the arena, but it can also enhance our performance while we’re competing. It dampens the fear response and allows us to take more risks that can help us win. What’s more, as journalist Po Bronson notes in Top Dog, testosterone “binds to androgen receptors in the brain’s reward system, making it more responsive to the rewards of competition, and helping it mount enough desire to overcome inhibitions. The result: less fear of risk, more drive for reward. The risk-reward calculation changes.”

Testosterone causes us to compete to win and not to lose.

While your “normal” T levels are inborn, and can’t be radically changed (without steroids) there are both long-term and short-term actions you can take to increase and optimize the amount of T nature gave you.

For insights on how to increase your testosterone in the long-term, read my article on how I doubled my T levels naturally in three months.

To prime your T right before a competition, try doing a power pose. You can also attempt to put yourself in an angry mood, perhaps by listening to some really angry music and doing some chest thumping and shadow boxing. Anger boosts your T, and some research shows it can be beneficial to winning a contest. For example, in experiments looking at different negotiation techniques, angry negotiators do better. They’re more focused on the terms of the negotiation and closing a deal.

But while research has shown that getting angry before a competition helps some folks’ performance, it’s also been found to hurt the performance of others. Staying cool, calm, and collected turned out to be the better approach for them.

Which approach will work for you? Experiment. Work yourself up into a mouth-frothing rage before some competitive endeavor and stay calm in another. Go with whichever approach gives you the biggest performance boost.

Chapter 11: Understand and Manage Your Competitive Desire/Style

Testosterone is a big biological factor in determining how one performs during a competition, but it isn’t the only one.

Much of whether a person rises to the occasion, or wilts under the lights of the arena, has to do with their genetics, specifically, what’s known as the COMT gene.

One mutation of the COMT gene allows individuals to thrive under pressure, while the other mutation can makes folks prone to choke. Because of the different responses to stress that the different COMT variations induce, geneticists often call the COMT gene the “Warrior/Worrier” gene: if you’ve got the COMT gene mutation for thriving under pressure, you’ve got the Warrior mutation; if you’ve got the mutation for wilting under pressure, you’ve got the Worrier mutation. Many folks have a combination of the two.

While the Worrier gene may sound wholly negative (everyone wants to be a “warrior”!), it can come in handy when times are calm. Worriers are better at making responsible decisions, planning for the future, and staying motivated to tackle essential but boring tasks like writing term papers and filing taxes.

Warriors, on the other hand, can handle stressful situations like champs, but falter during times of calm. They have a hard time staying motivated to complete tasks when there isn’t external pressure to do so; they need a sense of urgency, stress, or competition to get stuff done and perform optimally.

So being a Worrier or Warrior has its pros and cons. The key is simply understanding which you are so you can manage and make the most of your competitive style. You can actually get tested to see which COMT variation you have, but you already probably know intuitively which way you lean.

If you’re the Warrior type and shine when the pressure is on, then you should put yourself in competitive situations as much as possible. Get involved with sports when you’re young, and consider pursuing a competitive career.

If you’re more of the Worrier type, and tend to get flustered under pressure, you’ll need to be a bit more thoughtful in how you approach competition. You may wish to engage in it less, and choose jobs and hobbies where competition is less of an element.

However, you can’t, and shouldn’t, avoid competition entirely. Class rankings, negotiations, and even job interviews are, in a sense, competitions — ones you can’t get out of. And always skipping out on optional competition means you’re skipping out on the benefits that come with it, like self-improvement, enhanced creativity, and camaraderie.

Fortunately, if you want to pursue opportunities where there are unavoidably high stakes, you’re not doomed to folding under the pressure. For example, researchers found that some pilots with the Worrier gene perform better than pilots with the Warrior gene during simulated in-air catastrophic failures. The catch? Pilots with the Worrier gene who thrived in stressful situations had trained extensively for those types of situations. So being a Worrier can be an advantage in high-pressure situations so long as use your apprehensive disposition as motivation to practice for them.

The bottom line, then, is that if you’re a Worrier, you’ll need to be more proactive about managing your competition-induced stress by embracing rigorous practice and giving more heed to all the tips given above.

If you’re a Warrior, you’d still do well to heed the advice that’s been given, in order to even further enhance your performance and the benefits you get out of your much-beloved competitions. But know that you’ll also need to be more intentional about tackling life’s mundanities (you can start by planning your week)!

Chapter 12: Don’t Let Competition Canker Your Soul

“The important thing in life is not the triumph but the struggle. The essential thing is not to have conquered but to have fought well.” — Pierre de Coubertin, Father of the modern Olympics

Competition is like a virtue, which can be a powerful source for improving our souls and society, but, when take to an extreme, can become a vice.

Just as too gritty a stone can make a razor blade jagged, too much competition can coarsen a man instead of sharpen him. A scene in the film There Will Be Blood adroitly reveals the negative effects of excessive competition in a man. In it, the money-hungry oilman Daniel Plainview waxes about his all-consuming obsession with competition and in the process reveals how it has stripped him of his humanity:

Plainview: Are you an angry man, Henry?

Henry Brands: About what?

Plainview: Are you envious? Do you get envious?

Henry Brands: I don’t think so. No.

Plainview: I have a competition in me. I want no one else to succeed. I hate most people.

Henry Brands: That part of me is gone… working and not succeeding — all my failures has left me… I just don’t… care.

Plainview: Well, if it’s in me, it’s in you. There are times when I look at people and I see nothing worth liking. I want to earn enough money that I can get away from everyone.

Henry Brands: What will you do about your boy?

Plainview: I don’t know. Maybe it will change. Does your sound come back to you? I don’t know. Maybe no one knows that. A doctor might not know that.

Henry Brands: Where is his mother?

Plainview: I don’t want to talk about those things. I see the worst in people. I don’t need to look past seeing them to get all I need. I’ve built my hatreds up over the years, little by little, Henry… to have you here gives me a second breath. I can’t keep doing this on my own with these… people.

So how can you make competition a virtue in your life instead of a vice, and use it to boost rather than sap your humanity?

By actually being an absolute champion of competition, in all its purity.

Those who truly love the soul and spirit of competition don’t participate in it just to win, but because they love the fight itself. They love the struggle. They love the way it brings out the fullest potential of human beings, and weighs and sifts competitors until the most skilled and spirited rise to the top.

This love keeps them from engaging in unethical practices. Competition wouldn’t be competition without a level playing field, and victory wouldn’t be sweet if they cheated to win. Thus, they not only play fairly themselves, but advocate for fair play in others.

They lose with grace, and respect their rivals. They love their “enemies,” for they show them where their weaknesses are, and how they can improve. They support those who fall far short of the top as well, celebrating that glorious and wholly unique aspect of humanity which chooses to struggle when they could be comfortable.

They want everyone to enjoy the thrill of competition, the magnificent sparks created from battles of will and skill, and so do all they can to bring out competition’s best qualities.

Those who love the pure essence of competition harness their inner Spartan, rather than their inner Plainview, and end up loving humanity more, not less.

Conclusion

“It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.” — Theodore Roosevelt

For thousands of years, men have used competition to better themselves: to prove their manhood, test their skill, identify their weaknesses, strengthen their bodies, sharpen their minds, and bond with their brothers.

In the modern day, competition has taken on some negative connotations. There are those who worry that its attendant stress will harm the psyche and performance of those who don’t naturally thrive in a competitive environment, and that the losers will suffer a devastating blow to their self-esteem. There is concern as well that competition can lead to unethical and domineering behavior.

Yet none of those deleterious effects are the necessary consequences of competition. Competition is a neutral tool, which can be used for good or ill, all depending on how it’s utilized.

In an environment in which honor, integrity, respect, and fair play are emphasized, competition can lead to greater cooperation and a viscerally embodied sense of morality.

When the desire to be the best is healthily harnessed, competition can spur higher heights of creativity.

If pre-performance nerves are embraced as the body’s preparation for challenge, and high-stakes situations are practiced diligently beforehand, everyone, regardless of their genetics, can thrive in the refining fire of competition.

Is there danger of hurt feelings in defeat? Of course. But there is greater danger in never being tested, never struggling against forces outsides yourself, never fulfilling your potential. In avoiding competition, and stripping it from our culture, there is risk that we will never collide with the weight of opponents and encounter the gravity of opposition — that we will float through the ether of an inflated evaluation of our talents and skill, and drift in ignorance of where we are weak and need to improve. In fleeing competition we avoid failure, but run into the arms of mediocrity.

In competition, there is stress, there is pressure, there is hurt and loss. There is blood. There is sweat. There are tears. But there is also the power to push beyond limits, to progress personally and as a society. In competition, there is a chance to be fully alive, to fully exist, to know who you are, where you are, and how you stand, so that — no matter the outcome — your “place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.”

Enjoyed Our Treatise On Male Competition?

Sign up for our newsletter to get a PDF of it to read later offline.

Sources

For further reading about the science and philosophy of competition, check out these books that we used for sources in this book.