Well, I finally decided to start an Art of Manliness podcast. Many of you have requested that we crank something out so you can get your daily dose of manliness during your commute or while you’re exercising. Now please keep in mind that I have zero experience with podcasting. So this first go of it is a little rough. Please bear with me these first few episodes as I get my podcasting legs under me.

Here’s what I have planned for the AoM podcasts:

- The podcasts are going to be pretty short; no longer than 30 minutes.

- I’m going to shoot for once a week on Tuesday.

- It’s not going to be just me blabbering for 15 minutes about manly stuff. Instead I’m going to be interviewing authors, experts, and personalities that AoM readers would be interested in hearing from.We’ll discuss issues and topics of interest to men.

- I also plan on doing a bi-weekly series called “Man Stories.” I’ll bring on a regular AoM reader and simply ask him what manliness means to him, which men have influenced his perception of manliness, and when he felt like he became a man. Think NPR’s “This I Believe,” except for manliness. Should be interesting.

So that’s the general plan, and I’ll just play it by ear and see how it goes and what kind of response I get. Now let’s get this thing started.

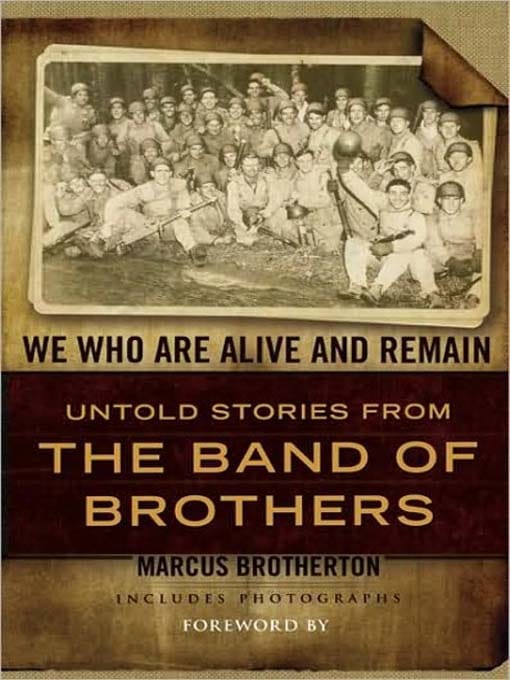

For the inaugural episode of the podcast, we talked with Marcus Brotherton, author of We Who Are Alive and Remain: Untold Stories From the Band of Brothers. For his book, Marcus interviewed surviving members of the 101st Airborne Division’s Easy Company who fought in WWII. The men of Easy Company were the subject of HBO’s mini-series Band of Brothers. In our interview, Marcus shares his insights about the men who fought in WWII and what lessons men today can take from the Band of Brothers.

Make sure to check out Marcus’ book, We Who Are Alive and Remain. It’s filled with great stories from a great group of men.

Listen to the podcast!

Read the Podcast Transcript

Brett McKay here, and welcome to the inaugural episode of The Art of Manliness podcast. I’ve got to say I am really excited about this. I have been wanting to do a podcast for quite some time. We’ve been getting emails from you all requesting that we start a podcast for The Art of Manliness. So, here we are. We’re doing it.

To give you an idea of what we have in mind with the podcast, we’re going to do an episode once a week. They’re going to be between 20 and 30 minutes long. It’s not going to be me just pontificating and blabbering on about what I think is manly or whatever. I wouldn’t do that to you all. What we plan on doing is bringing in experts, authors, personalities, and Art of Manliness readers, you all, who read the blog, and talk to them. Discuss with them issues and topics of interest to men. Ask them what manliness means to them. Hopefully, get some advice and some tips on how to be better husbands, better fathers, and all around better men.

So that’s the goal of the show. I am looking forward to it. Sit back, relax, and enjoy the first episode of The Art of Manliness podcast.

[theme music]

Brett: During World War II, the United States Army developed an experimental fighting force that parachuted soldiers from C-47 transport planes behind enemy lines. The 101st Airborne Division or Screaming Eagles is one of America’s most well-known military divisions. Within that division, a company of soldiers called Easy Company took part in some of the most famous events of the Allied campaign in Europe, including but not limited to the D-Day invasion, the Battle of the Bulge, concentration camp liberations, and taking over Hitler’s mountaintop fortress, the Eagle’s Nest. The men of Easy Company have been the subject of numerous books and also the HBO miniseries “Band of Brothers.”

Our guest today has recently published a book about Easy Company. His name is Marcus Brotherton and his book is called “We Who Are Alive and Remain: Untold Stories from The Band of Brothers.” Marcus is a journalist and has written or co-written over 17 books, including a memoir of Easy Company’s Lieutenant Buck Compton. Marcus lives in the beautiful state of Washington with his family. Marcus, welcome to the show.

Marcus: Thanks, Brett.

Brett: So, Marcus, a lot has been written about Easy Company, the 101st Division. You’d think there wouldn’t be anything else to say about them. So what inspired you to take on this project and write the book?

Marcus: That’s a great question, Brett. At the start of Dick Winters’ memoirs, he says that he often receives letters from people and they say things like, “Tell us more.” People are searching for as complete a story as possible about this company. For me, personally, it was just a chance to work with great people. These guys are living history and legends. I knew I had much to learn from these men.

Brett: I remember you mentioned in your book, and I think in the epilogue, that you were living in an apartment with this World War II veteran. I think Nate Miller was his name?

Marcus: Yeah. Yeah.

Brett: Well, tell us about Nate. It sounds like he kind of inspired you or connected you with these men.

Marcus: Yeah. It was back in graduate school. I moved down to L.A. and I didn’t know anybody. He was my advisor’s father. He had just lost his wife, and his son thought that it might be good for him to have some company in the house. So, I rented a room from this guy. He was really my first introduction to anybody from World War II sort of in living color, so to speak. Nate was an amazing man. He was very ornery and slept with a loaded gun under his pillow.

Marcus: He just had these amazing stories about things he had done in the war. It had really colored his world view in so many ways. He saw much of his life through the grid of what he had experienced.

Brett: Wow. So from there, I guess he planted the seed for you to do these projects. I mean, you’ve written a book with Lieutenant Buck Compton, his memoirs, and now you’ve written this book. So, I guess he kind of planted the seed for you to do this project.

Marcus: Yeah, it’s been really cool. I never thought I would write military nonfiction. I didn’t major in history. I’ve been a journalist and collaborative writer. Buck Compton is just great. He lives just about 40 minutes from my house. We connected a couple of years ago to write his memoir. One thing leads to another. So Buck’s book got me connected with this one.

Brett: Wow. That’s great. How many men of Easy Company are still alive?

Marcus: Yeah. It’s a good question, Brett. There’s probably about 30. Although there is really no way to know for sure. You know, after the war, some of the men just sort of disappeared. So they didn’t keep in contact with any of the associations or their friends. In fact, just this past week I was sent a newspaper article about a guy named Ed Mauser. He’s an Easy Company veteran. He is still alive and living in Omaha. He is 92 years old, going strong. He had never connected with any of his buddies from after the war. He is planning on coming to this year’s Easy Company reunion. For the first time in 60 plus years, he is going to connect with his buddies.

Brett: Wow. That’s great.

Marcus: It will be cool to meet him. Yeah.

Brett: That’s something else I thought was interesting in the book that a lot of these men didn’t start going to the reunions until the “Band of Brothers” book was written or the series was put on HBO. A lot of them didn’t have much to do with it, but somehow, this brought them back together.

Marcus: Yeah, you know, some of it was a coping mechanism. Dewitt Lowery, his method of coping was really to forget. He really chose to purposely not think about the war at all. I don’t think he’s ever been to a reunion, although he has connected with Dick Winters and some of the other men. Some of it was just a family thing where they came home, started working, raising families, and whatnot. Life gets busy.

Brett: Yeah.

Marcus: So, yeah. A variety of reasons for doing that.

Brett: Yeah. So, you know, Marcus, after talking to these men, did you notice any characteristics that they all had in common that made them such a successful military company?

Marcus: They were an elite, highly trained fighting unit. Definitely the training. Definitely their drive. I would say the single shared characteristic was probably determination. Many of them said things like, you know, “We were just doing our jobs. We didn’t quit. We didn’t give up.” I think that one of the men, Forrest Guth, he just passed away a couple weeks ago here, when Forrest was jumping into Holland for Operation Market Garden, his parachute malfunctioned. He’s jumping out of the plane, and because the men had jumped so low on that jump, below 500 feet, there wasn’t enough time to open his reserve chute. So he lands and he hits hard. He just lands with a thud, knocks him out, and when he comes to he can’t move his back or his legs.

Brett: Wow.

Marcus: So, they ship him to a hospital in England, take x-rays and whatnot, and discover he’s got a broken disc in his back. That was it. That was his golden ticket home if he wanted it. He could have been, you know, excused from the war. But anyway, he stays in the hospital for a while, regains some feeling in his legs and back. Although he is still under a great deal of pain, he makes the choice to go back to the front and continue the battle with his buddies. You know, he just didn’t quit. That’s determination.

Brett: Yeah. I actually noticed that there were several men that that happened to. They would get injured and it would be their golden ticket home. They could go home. But they would go AWOL from the hospital and find any way to get back to the front lines with their company.

Marcus: Yeah. Ed Joint was another man who did that. Yeah. They would rather fight than not.

Brett: Wow. You know, Marcus, one of the things we actually wrote a post about World War II vets being the “Greatest Generation.” I guess that is a title that Tom Brokaw came up with. A lot of people have criticized this moniker for these men who fought in World War II. Do you think the title “Greatest Generation” is appropriate for these men?

Marcus: Yeah, that’s a good question. I think the term greatest is sort of compared to something else and what it’s compared to. I think that one of the book’s contributors, a guy by the name of Clancy Lyall, he talks about how when he was engaged in combat any time he could shoot to wound an enemy as opposed to shoot to kill, that was always what he chose to do. One time he was fighting in Normandy in the town of Saint Margulies. A German popped out from behind a street. Clancy had a clean shot, he could take him out, and he chooses to shot him in the leg simply just to take him out of the battle. He says, “As far as it was up to me that was fine as long as he was not shooting back at me.”

A couple days later, Clancy is fighting in another town called Carentan. If you can picture it, it is close quarters, street to street fighting. Clancy is running around the corner of a building. Obviously, he can’t see around the other side. As he runs around the corner of this building, he runs smack dab into an enemy soldier who has his rifle outstretched and his bayonet fixed on the end. You can picture it. The weapon just sticks fast in Clancy’s gut. He runs straight in to it.

Brett: Wow.

Marcus: So, Clancy describes this scene how both he and the enemy are just absolutely frozen for a minute, staring at each other. Fortunately for Clancy’s sake, he raises his rifle and gets off the first shot. As the enemy is falling over backwards, the enemy pulls the bayonet out of Clancy’s stomach. Clancy, as he is telling me the story, he jokes. He says, “You know, I wasn’t shooting to wound just then.” That’s the type of men these guys were, and that’s the type of situations they encountered. They were placed in these extraordinary situations where they put their lives at risk. It wasn’t for fame or for recognition but because they knew it was the right thing to do for the sake of future generations and our liberty.

Brett: Yeah.

Marcus: So, certainly that is admirable.

Brett: Yeah, definitely. You know, one thing I liked about your book, as opposed to a lot of other nonfiction military history books, is it’s not; it’s different that you’re basically just interviewing these veterans and you are letting them tell their stories. You are not really editing it. You’re not trying to format it. You’re just letting them speak, and it’s basically just transcripts of them telling their stories. Why did you go with this approach as opposed to a typical Stephen Ambrose history book where you try to come up with a cohesive storyline?

Marcus: Right. Right. Yeah, it’s an oral history book for sure. It’s funny. The book has received good reviews and really great acclaim across the board. I’ve received a couple of criticisms from guys who basically say, “Look, you’re not an author. Basically all you did was just turn on a tape recorder and type in what you heard.” Not to defend myself here, but I can assure you that the project took more editorial work than that . . .

Brett: Yeah, I’m sure.

Marcus: . . . to achieve that oral history effect. Really, I wanted to take myself out of the way as an author. Stephen Ambrose says, “Always let the men speak for themselves.” I wanted to connect readers directly with the men. It is kind of this feeling that they are sitting down in the living room together with you and just telling their stories and you are getting to know these guys, you know, watching a football game together.

Brett: Yeah. Yeah. So, Marcus, I can imagine, I mean, after talking to these men, you can’t walk away from this unchanged, you know, listening to these stories. How did writing this book and taking part in this project change you as a man?

Marcus: You know, thinking about the men of Easy Company training at Camp Toccoa in Georgia, they’re running up Mount Currahee every morning, every evening sometimes. Three and a half miles up, three and a half miles down. You know, if they can do that, then I can certainly go for my morning jog without my usual amount of complaining. So, you know, it helps me be less of a whiner basically.

Brett: Yeah.

Marcus: It helps me see my life’s challenges and problems in perspective. I’m not sleeping outside in the snow. I’m not getting shot at.

Brett: Yeah.

Marcus: It definitely helps me be more grateful. The fact that I can write books for a living today instead of working in some factory for one of Hitler’s descendants, that’s due in part to the veterans of World War II.

Brett: Wow. Marcus, after, you know, talking to these men, and I am sure you gleaned some characteristics that they had, what do you think are some lessons that men in today’s generation can take from the men of Easy Company?

Marcus: Stephen Ambrose said, “All men ultimately want to know two things.” To whom do I owe thanks that I should live in such opportunity is the first thing. And the second is, will I have the courage when the time comes? Studying about the men at Easy Company helps us answer those questions. They have given much so that we can live for what matters. As men today, we’re often told to seek lives of entertainment or leisure or misguided sensuality. The big lesson for us is to live courageously, to live selflessly, to think of our communities and families. The invitation is to man up and stop playing video games all day. Put our pants on and basically go do something amazing with our lives.

Brett: Well, our guest today was Marcus Brotherton. His book is called “We Who Are Alive and Remain: Untold Stories from the Band of Brothers.” Marcus, thank you for talking with us. It’s been a pleasure.

Marcus: Thank you, Brett.

Brett: That wraps up this edition of The Art of Manliness podcast. Make sure to check back at The Art of Manliness website at ArtofManliness.com for more manly tips and advice. Until next week, stay manly.

[theme music]

This transcript brought to you by www.SpeechPad.com.