Welcome back to our series on the libraries of great men. The eminent men of history were often voracious readers and their own philosophy represents a distillation of all the great works they fed into their minds. This series seeks to trace the stream of their thinking back to the source. For, as David Leach, a now retired business executive put it: “Don’t follow your mentors; follow your mentors’ mentors.”

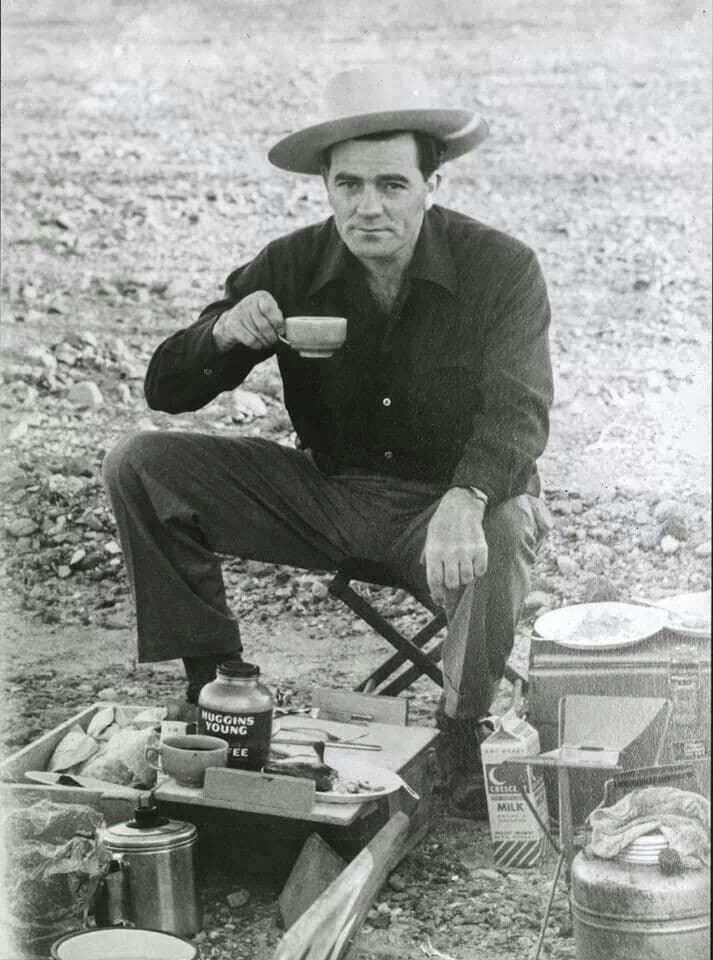

When digging in to the best novels and authors in the Western genre of literature, there are a few names that pop up over and over again. Larry McMurtry, Cormac McCarthy, Zane Grey, and of course, Louis L’Amour. Over the course of his prolific career, L’Amour published over 100 books — most of them novels, but also over a dozen short story collections, and one brilliant autobiography, Education of a Wandering Man, which is more of a journal of his prodigious reading rather than a life telling (note: all quotes in this piece are from that book). Amazingly, not a single novel of his was published until 1951 when he was in his early 40s, though he had been writing poems and stories his whole adult life.

Though he’ll rarely be praised for writing beautiful or lyrical prose, L’Amour is one of the top 25 bestselling authors of all time, and when you ask grandpas — yes, as a whole category — about their favorite authors, he seems to almost universally top their lists. L’Amour writes with a realistic quality that isn’t easily matched in the genre, balancing both the romance and realities of Western life. His action scenes are superb, but more striking are his lifelike depictions of the landscape, the horses and horsemanship, the movements and habits of American Indians. Few have ever researched and truly lived the West like L’Amour.

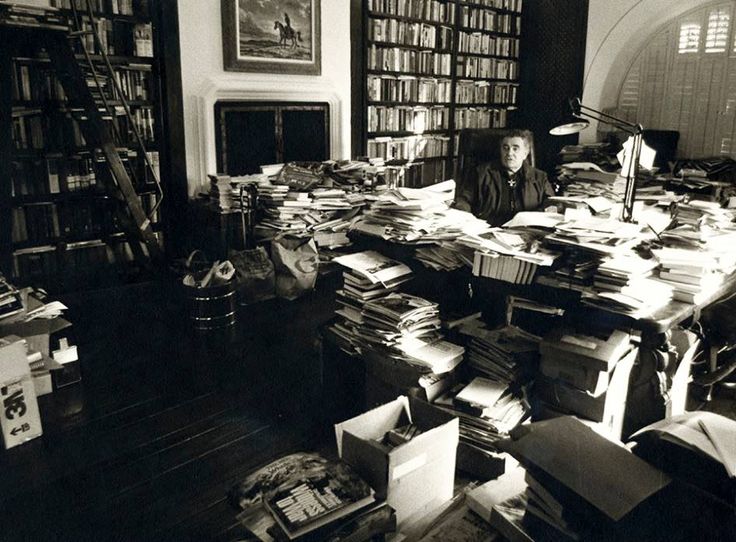

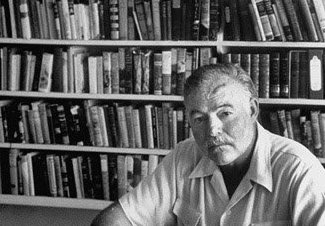

As a reader, L’Amour’s only match may have been Theodore Roosevelt himself. The Western writer had a library of over 10,000 books, and averaged reading 100-120 books per year — “reading approximately thirty books a year on the West in its many aspects” both for pleasure and in order to stay on top of his writing game.

And it wasn’t just books either — he regularly read magazines, newspapers, and even small town pamphlets and brochures. He noted that it was in those smaller collections of the printed word where one got into the nitty gritty of understanding things and that “They are often valuable additions to the larger pages of history.”

He was also an avid collector of Little Blue Books — small, pocket-sized informational booklets — noting “I carried ten or fifteen of them in my pockets, reading when I could,” and that he had “read several hundred” of them.

Louis L’Amour’s life story is in fact primarily a love affair with books. He had this to say about his motivation to be a successful writer:

“To me success has meant just two things: a good life for my family, and the money to buy books and continue the education of this wandering man.”

Before we take a look at the specific books that influenced L’Amour, let’s take a brief look at his story, and how he came to be such an avid reader.

The Origins of Louis L’Amour’s Love Affair With the Written Word

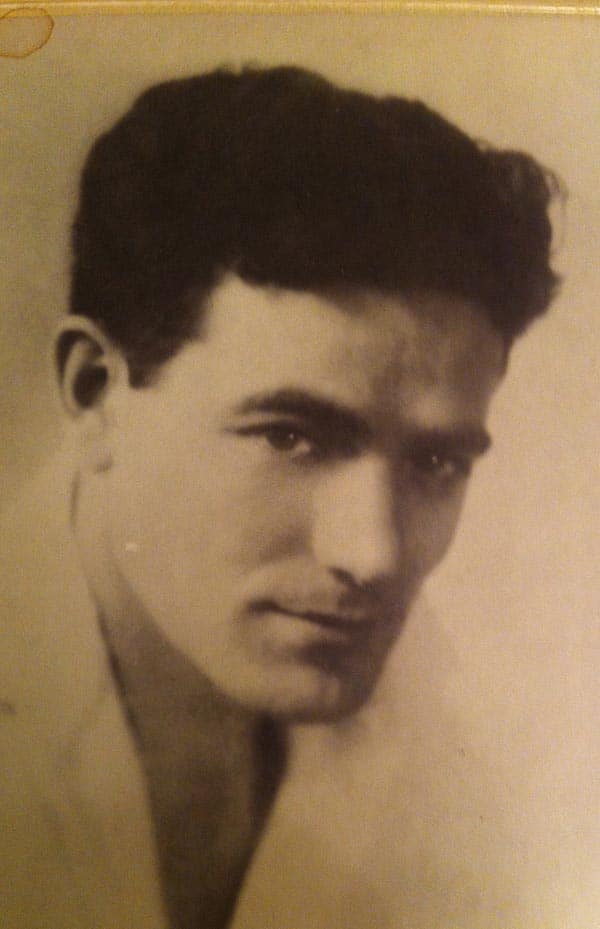

Louis was born in 1908 in Jamestown, North Dakota, the 7th and final child born to Louis and Emily LaMoore (it was later that the younger Louis changed the spelling of his last name to L’Amour — its original rendering — to honor the legacy of his French ancestors).

As a child, his family had a modest collection of books, but it was at the library that his love of reading really came to life. His oldest sister, Edna, was a librarian, and Louis spent long hours in the stacks exploring subjects that his schooling only tangentially covered.

At home, that learning was cemented with further reading and discussion:

“Ours was a family in which everybody was constantly reading, and where literature, politics, history, and the events of the prize ring were discussed at breakfast, lunch, and dinner.”

In fact, he said that “reading was as natural to us as breathing.”

Because of economic difficulties, the family moved to Oklahoma in 1923, and Louis dropped out of high school to become an itinerant worker; though he doesn’t give many personal details, it’s likely he struck out on his own because he didn’t wish to be a financial burden at home. From logging in the Pacific Northwest, to cattle skinning in Texas, the young man traveled all across the country (and the world), taking any job that would put a meal in his belly, and fund his reading.

L’Amour was in fact tramping around the Far East on freighters — Singapore specifically — when his old high school classmates graduated. At that time he specifically remembers reading Departmental Ditties, a poetry collection by AoM favorite, Rudyard Kipling.

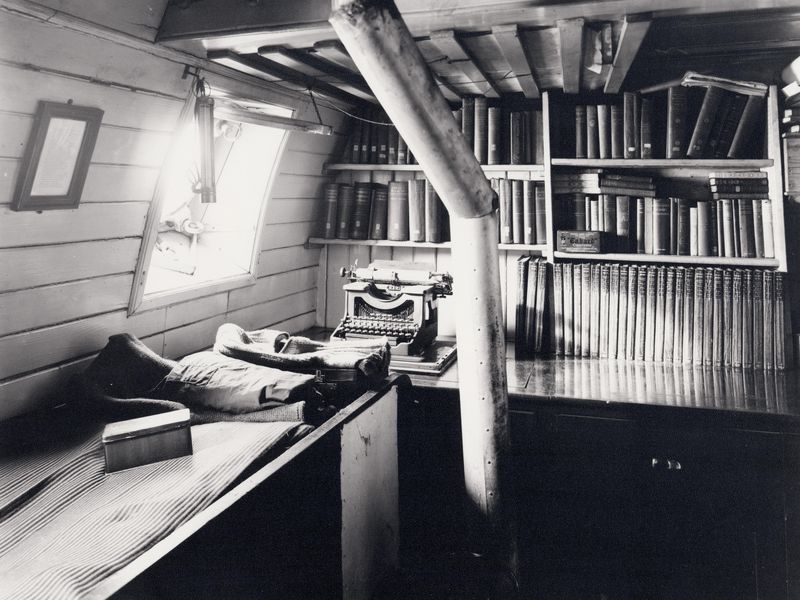

Until WWII, L’Amour’s life was a series of manual labor jobs. He was an abandoned mine caretaker (guarding against thieves and vagabonds), ditch digger, cargo officer on ships, logging inspector, amateur boxer, and more. Through it all, the bachelor noted, “I was never without a book, carrying one with me wherever I went and reading at every opportunity.”

Even then L’Amour knew he wanted to make his true living as a writer — preferably as a poet. So when he wasn’t reading or working, he was writing. When his poems didn’t catch commercially, he tried his hand at short stories, in a variety of genres — Far East adventures, boxing tales, Westerns. He wrote about nearly everything. Finally in the late 1930s, his stories started being accepted by the pulp magazines that were popular at the time.

Then WWII came. While at age 35 he was too old to see active combat, Louis served stateside as a winter survival instructor (employing skills learned from growing up in North Dakota), as well as two years in Europe commanding a fleet of gas tankers. During the war, as you can imagine, he avidly consumed the Armed Services Editions of the popular books of the time.

Upon returning from the war, magazines and publishers were looking not for the adventure stories that Louis previously had success with, but mysteries and Westerns. They were all the rage. Given the traveling and working L’Amour did in the West, that’s the direction he followed, not out of passion necessarily, but because that’s where the market was leading him and where he ultimately found success. After getting over 100 short stories published in the next decade or so, he finally landed his first novel in 1951, Westward the Tide.

From then on, he cranked out multiple books a year. He found love and married Kathy Adams in 1956, and together they had a son, Beau (1961), and a daughter, Angelique (1964). Details about his family life are not easily found (he was a rather private fellow), but Louis kept up his torrid reading and writing pace until he died in 1988.

Louis L’Amour’s Philosophy of Reading

1. Reading is your education. Even though Louis didn’t graduate high school, and his only college degrees came much later in life in the honorary form, he received quite an education, entirely of his own doing. He realized that to be successful, he would need to be educated, and that college was not in his cards. So he pursued an autodidactic curriculum of his own volition:

“The idea of education has been so tied to schools, universities, and professors that many assume there is no other way, but education is available to anyone within reach of a library.”

And what did he expect of his self-made education? What was he hoping to gain? He explains:

“If I were asked what education should give, I would say it should offer breadth of view, ease of understanding, tolerance for others, and a background from which the mind can explore in any direction. Education should provide the tools for a widening and deepening of life, for increased appreciation of all one sees or experiences. It should equip a person to live life well, to understand what is happening about him.”

Reading should expand your worldview and open you up to new ideas. It can and should provide frameworks and the basic foundation of a life well lived. That is why Louis credits books with saving his life — without them he would have been a permanent vagabond, perhaps dying too young in a work accident or a street fight (as many acquaintances of his did).

2. You have time to read. Make time to read.

“Often I hear people say they do not have time to read. That’s absolute nonsense. In the one year during which I kept that kind of record, I read twenty-five books while waiting for people. In offices, applying for jobs, waiting to see a dentist, waiting in a restaurant for friends, many such places. I read on buses, trains, and planes. If one really wants to learn, one has to decide what is important. Spending an evening on the town? Attending a ball game? Or learning something that can be with you your life long?”

Life’s many spare moments are packed with possibilities. Don’t let them be wasted on scrolling through Instagram or playing the latest fad game. The next time you find yourself with a small gap of time, crack open a book, and snatch a spot of reading.

3. Read what’s in front of you, and what’s fun and entertaining.

“Whatever the book, a reader reads.”

For Louis, his reading was largely determined by what was available wherever he was working. From small bookshops overseas, to borrowing titles from shipmates, there just wasn’t much choice in what he was reading, especially in his earlier years.

For most of us, our modern situation is a bit different. There are books everywhere. In fact too many books perhaps. You can go to a used bookshop or a Goodwill and grab a paperback for a buck (or even less sometimes).

Our problem is more that we actually have too much choice, and it paralyzes us. My personal library — both physically and digitally — has perhaps hundreds of unread books, and I often just stare at it, wanting to pick the perfect title to dig into next (sometimes even before I’ve finished something). Don’t fall into that trap of being overwhelmed by endless options; just pick something and start reading.

This goes against the grain of Emerson’s reading advice, but if you’re someone who just needs to read more or who needs to get started reading in the first place, this is the way to go. Just read what’s right in front of you and what you’ll truly enjoy rather than searching for the perfect book that will perhaps make you seem cultured. As L’Amour suggests:

“For those who have not been readers, my advice is to read what entertains you. Reading is fun. Reading is adventure. It is not important what you read at first, only that you read.”

4. Think about, and share with others, what you’re learning.

“It is not enough to have learned, for living is sharing and I must offer what I have for whatever it is worth.”

Living is sharing. Isn’t that a wonderful idea? Whatever you’re reading and learning about, make a point to share it with others. Start a book club (my wife and I have been in one for a few months now, and it’s wonderful). Write a blog post or just a Facebook update with some good quotes. Share your insights or questions or thoughts at the dinner table with your family.

Beyond just sharing your reading, make a point to think about it throughout the day, especially in moments of solitude:

“A book is less important for what it says than for what it makes you think.”

When you’re taking time to think about what an author (or character) has said or done, you’ll have more insightful tidbits to share with others. You’ll be able to construct fuller mental models, and connect different ideas to each other in creative ways — something in high demand in our Google-driven world in which rote facts are accessible in mere seconds, but deeper analysis is rare. It’s especially easy to do this when performing menial manual tasks like weeding or washing the dishes. L’Amour noted that “Often when chipping rust or touching up paint, I thought about what I had been reading.” You’d be well-served to do the same.

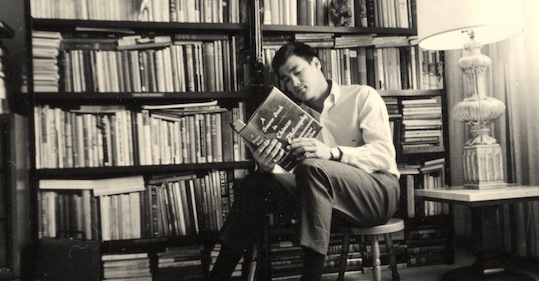

5. Read what others have read!

“I have enjoyed digging into the reading habits of many great men and women and have tried where possible to get a list of the books in their libraries. . . . I hoped that by understanding the books these men and women read I might grasp at the basic sources of some of their ideas.”

I was thrilled to find out that L’Amour himself was a man who dug into the reading habits and libraries of people he admired. That’s what this series is all about, and I have to think he’d be proud of the fact that folks are diving into his habits and collections in order to grow and find some reading inspiration.

What makes the reading list below unique is that for many of them we get not just a title, but what L’Amour thought of and took away from that title. It’s a real joy to peruse the list. This is truly but a small fraction of the books mentioned in Education of a Wandering Man. If you’re a reader, and you should be, I cannot recommend enough picking up a copy. Mine is riddled with underlining and marginalia, and I know I’ll be returning to it again and again.

A Very Partial Louis L’Amour Reading List

- The Annals and Antiquities of Rajahstan by James Tod — “a source for several planned books”

- Ralph Waldo Emerson’s essays

- Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson — “one of the first books I read”

- History of the World — he doesn’t mention the author, so I’m not exactly sure which book this is, but his memory of it was too good to pass up: “when my father came home I would sit on his knee and tell him what I read during the day.”

- Black Beauty by Anna Sewell

- “A dozen Horatio Alger novels”

- A Princess of Mars by Edgar Rice Burroughs

- Ivanhoe by Sir Walter Scott

- Ben-Hur by Lew Wallace

- The Count of Monte Cristo and The Three Musketeers by Alexander Dumas — “It was a great day when I discovered on the shelves of the library a set of forty-eight volumes by Dumas, and I read them, every one.”

- Les Miserables, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, The Man Who Laughs, and Toilers of the Sea by Victor Hugo — “The last-named was my favorite.”

- Leatherstocking Tales (a series of 5 novels) by James Fenimore Cooper — “Enjoyed them.”

- The Bar Sinister by Richard Harding Davis — “a story about a dog, and a good yarn.”

- Martin Eden by Jack London — “prepared me for the rejections to come, and the difficulty I would have in getting published.” Also by London: The Sea Wolf, The Call of the Wild (“another great dog story”)

- The White Company by Arthur Conan Doyle — “an exciting, romantic story.”

- The Adventures of Gil Blas by Alain Rene Lesage — “I read it not once but twice on the plains of West Texas.”

- Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes — “marvelous stuff.”

- Hamlet by Shakespeare — “[Shakespeare] was the ultimate professional, a writer who knew what he was doing all the time.”

- The Odyssey and The Iliad by Homer — “I often thought how like some of his characters were men whom I had met.”

- The Life of Samuel Johnson by James Boswell — “without doubt one of the greatest biographies in the English language. It was a book I read slowly, often returning to reread parts of it.”

- Lord Jim by Joseph Conrad — “I have read several times . . . and which for me was a real discovery.”

- Ecce Homo, The Birth of Tragedy, Thus Spake Zarathustra, and The Will to Power by Friedrich Nietzsche

- Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoyevsky — “surprised by this book — surprised and very impressed. Several times I turned back to reread sections of the book.”

- Kim by Rudyard Kipling — “read it twice.”

- Candide by Voltaire — “it was a revelation. I loved it, rereading it at once.”

- Commerce of the Prairies by Gregg — “one of the basic books of the westward movement”

- My Life on the Plains by George Custer

- The Art of War by Sun Tzu, The Military Institutions of the Romans by Vegetius, On War by Carl von Clausewitz — “military tactics had interested me since my youth”

- The Case of Sergeant Grischa by Arnold Zweig — “the best novel to come out of World War I, although Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front attracted more attention and was a good book also.”

- Lives by Plutarch — “In several of my western novels I have had characters reading Plutarch. I believe more great men have read his Lives than any other book, except possibly the Bible. … In reviewing the reading histories or libraries of great men, I have come upon him again and again, and justly so. His is a sophisticated, urbane mind dealing with aspects of leadership.”

- The Prince by Niccolo Machiavelli

- The Red and the Black by Stendhal

- Wuthering Heights by Emily Bronte

- Walden by Henry David Thoreau

- To Have and Have Not by Ernest Hemingway, also his story “Fifty Grand” — “one of the best fight stories every written. Jack London’s ‘The Mexican’ is another.” L’Amour wrote that he “enjoyed Hemingway’s short stories more than his novels.”

- Historic Sketches of the Cattle Trade by Joseph McCoy — “an excellent book and one of the basic books on that aspect of the west. J. Frank Dobie’s The Longhorns is another.”

- The Log of a Cowboy by Andy Adams

- The Life of Billy Dixon by Olive Dixon — “I managed to stay awake most of the night to finish the story . . . Recently I reread the book and found it every bit as good as I had remembered.”

- Six Years With the Texas Rangers by James Gillett

- The Koran — “I find it has much to offer”

- Journal of a Novel by John Steinbeck

- The Decline of the West by Oswald Spengler — “read, but by too few”