When it comes to self-improvement, most people set big, audacious goals. Setting those goals feels good. It pumps you up and you feel like you can conquer the world. But then . . . it happens. You have a setback and within a matter of days, your fiery ambition to change yourself is extinguished. And so you’re back to where you started, only you’re even worse off than before because you’re saddled with the sting of failure.

But what if I said there’s a much more effective way to improve yourself and it just requires getting 1% better each day? It’s called the Kaizen method. It sounds like a mystical Japanese philosophy passed down by wise, bearded sages who lived in secret caves, but it actually has a surprisingly American and modern origin. My guest today has written a book about this philosophy of small, continuous improvement used by Japanese carmakers for over 60 years. His name is Robert Maurer and his book is One Small Step Can Change Your Life: The Kaizen Way.

Today on the show, Robert explains the American roots of this Japanese manufacturing process and how the Japanese re-introduced it to America in the 1970s. He then digs into the psychology of why the Kaizen method of improvement works so well not just for organizations but for individuals. We end our conversation with the practical ways you can incorporate Kaizen in your own life.

Show Highlights

- The history of the Kaizen philosophy

- The American roots of Kaizen

- Kaizen in car manufacturing

- What Japanese companies taught American ones in terms of manufacturing

- The myths that people believe about behavior change

- Incorporating Kaizen into individual lives vs. big corporations

- How Kaizen can help you get better sleep, exercise more, and live an overall healthier lifestyle

- The power of visualization

- Why you should be asking yourself small, seemingly trivial questions

- Using Kaizen to get yourself out of debt

- How managers and parents can use small questions

- How small is small enough when it comes to thoughts and actions?

- The way that small steps can actually lead to big steps

- How Robert used Kaizen to write his book about Kaizen

- Reinforcing your actions with equally small rewards

- How Robert got himself to floss every day

- Finding small problems that will have a big payoff when solved

- How Kaizen in one area of your life transfers into other areas

Resources/People/Articles Mentioned in Podcast

- The Machine That Changed the World

- W. Edwards Deming

- Podcast: The Science of Lasting Behavior Change

- Get 1% Better Every Day: The Kaizen Way to Self-Improvement

- Become a Self-Starter: The Importance of Autonomy

- Mind Sculpture

- Microhabits: Creating Habits That Stick

If you’re tired of fits and starts in your self-improvement, you need to read One Small Step Can Change Your Life. Robert does a great job providing research-backed advice on how to start and maintain growth for the long-term.

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Podcast Sponsors

Mack Weldon. Their underwear and undershirts are second to none. If you don’t like your first pair, you can keep it, and they will still refund you. No questions asked. Go to MackWeldon.com and get 20% off your purchase using the promo code MANLINESS.

Cooper Tires. Your four tires are all that connect you and your car to the road, so it’s important to be sure you can rely on them. Cooper Tires has more than a century of experience in manufacturing comfortable, capable tires. Visit coopertires.com today.

Click here to see a full list of our podcast sponsors.

Recorded with ClearCast.io.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Welcome to another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. Well, when it comes to self-improvement, most people set big, audacious goals, and setting those goals, it feels really good because it pumps you up and you feel like you can conquer the world, but then it happens. You have a setback, and within a matter of days, your fiery ambition to change yourself is extinguished, and so you’re back to where you started, only this time, it’s worse than before because now you’re saddled with a sting of failure, but what if I said there’s a much more effective way to improve yourself, and it requires just getting 1% better each day?

It’s called the Kaizen method, and while it might sound like a mystical Japanese philosophy passed down by wise, bearded sages who lived in secret caves, been watching Ninjago lately with my son, it actually has these surprisingly American and modern origins. My guest today has written a book about this philosophy, a small continuous improvement used by Japanese car makers for over 60 years. His name is Robert Maurer, and his book is One Small Step Can Change Your Life: The Kaizen Way.

Today on the show, Robert explains the American roots of this Japanese manufacturing process and how the Japanese reintroduced it to America in the 1970s. He then digs into the psychology of why the Kaizen method of improvement works so well, not just for organizations but for individuals, and then we end our conversation getting into some really practical ways you can incorporate Kaizen in your life and get better one small step at a time.

If you’re tired of being on the self-improvement rollercoaster, this episode is for you. After the show’s over, check out the show notes at aom.is/kizen, that’s K-I-Z-E-N.

Robert Maurer, welcome to the show.

Robert Maurer: It’s a pleasure to be here.

Brett McKay: You wrote a book called One Small Step Can Change Your Life: The Kaizen Way. Before we get into what Kaizen is, because we were going to get into detail what that is, how did you get started into researching this Japanese, it’s a manufacturing philosophy, really, that got exported back to the United States, but how did you, what’s your background where you got interested in this.

Robert Maurer: Well, I’m a clinical psychologist, and I have an unusual position. I work in a family medicine clinic, a family medicine residency clinic, so we’re training family practice doctors. I get to go in the room and see physicians as they interview a patient for all the things that bring people to a primary care clinic. Here was an opportunity to identify people at risk for future problems and try to help them before they made poor marital choices, before their children started developing problems, before they got depressed, but we had no tools.

Long story short, I began researching long-term studies where they follow people from birth until they were 40, 50, 60, 70 years old to see what skills allowed people, in spite of adversity and setbacks, to continue to thrive not just in jobs, not just in health, not just in relationships, but all three.

There were just about two dozen studies that have done this, but what led me to Kaizen was seeing that, one day I was looking at a newspaper article, and it said that Toyota Lexus for the umpteenth year was the most high quality car made. I thought, well, maybe there’s something metaphorically about building a car that I could use to help people build their lives. That led me to a book called The Machine That Changed the World, which you think would be about computers, but it’s actually about cars, and that led me to Dr. Deming and Kaizen.

Brett McKay: It all started with helping people make big changes in their life that are good for themselves and making those changes endure. That’s a big problem, right, and in medical field, make sure people take their medications, making sure people eat right, making sure people exercise.

Robert Maurer: Exactly.

Brett McKay: For our audience who aren’t familiar with Kaizen, can you tell us what it is, what’s the big tenant and the history of its development?

Robert Maurer: It was, in some ways, a two-prong story. In the one sense, it’s an ancient Asian philosophy, the journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step because Kaizen has two definitions, but one is making extremely small steps in order to accomplish a large goal. The other definition is looking at very, very small moments to learn large lessons, but the modern history of it is, as you know, the US entered World War II very suddenly with very little human or material resource.

A group of Americans led by a man named Edward Deming tried to, as we were turning car factories into tank factories with very little resource, tried to help make the products as good as they could. They would tell each worker on the assembly line, “See if you can find even the smallest ways to try to improve the process or the product,” because again, we couldn’t make big wholesale changes, and they found to their surprise these very small incremental changes led to big, innovative results, and so the idea of taking small steps to accomplish large goals became part of the manufacturing process.

After World War II, Deming and his colleagues introduced this to Japan as they were rebuilding out of the rubble of the war. Small struggling firms like Toyota embraced Kaizen. They call it their soul and began building some of the highest quality products in the world.

Brett McKay: With the Kaizen one, the car manufacturing, basically, the manufacturer or the company gave the on-the-ground employees the permission to stop the conveyor belt, so to speak, and make those changes, which was often unheard of in American factories. You never stop the conveyor belt. You kept it going no matter what, but there they were. You stop it, if you can improve it, let’s do that right then and there.

Robert Maurer: Exactly. It’s one of the ways the Kaizen works in terms of preventing mistakes because as you say very well, prior to Deming and Kaizen, cars would go down the assembly line, and at the end of the line, workers would look to see how many problems there were and no matter how much you paid for the car, whether it was a Ford or a Ferrari, you still came back to the dealer a week later with 10 things that needed to be fixed.

Well, Deming and his colleague at Toyota named Taiichi Ohno decided, “We’re not going to do that.” Cars going down the assembly line, as you pointed out, and somebody sees a scratch on the fender, they stop the assembly line, bring in the supplier or the engineer and tried to fix it there, and everybody thought Deming was crazy. How can you mass manufacture a product when you’re stopping at every few feet to fix it?

Turned out to be the most efficient way to build cars, and since then, everybody’s adopted that philosophy.

Brett McKay: Actually, what ended up happening were, these Japanese manufacturers, Toyota in particular, they started beating the big car, American car companies, Ford, Chevy, and GM actually sent people to Toyota to figure out how can we implement this Kaizen.

It’s kind of weird to like, it started in the United States, went to Japan, and then Americans had to go back to Japan to rediscover this thing.

Robert Maurer: It’s very true. That’s exactly the history of it, yeah. In some ways, it makes sense because after World War II, we were the only industrial giant still standing. People were buying our cars and refrigerators no matter how we built them, so until the Japanese started to really make inroads into our consumer world, nobody got interested in Deming and Kaizen.

Brett McKay: What’s interesting is like, why, I mean, so these car companies saw what Deming was doing with the armory of democracy, building these things really fast, and it was working. Why did they decide like, “Nah, we’re going to go back to the way we used to do things before the war.”

Robert Maurer: I think they probably assumed it was cheaper. If you’re building 7,000 cars a day, it just seemed logical to keep the assembly line moving and fix the problems later. It just seemed logical to them, and because they had no competition and a huge consumer base of soldiers coming back from the war and wanting to buy new cars, it was hard for them to try to take a harder look at what was happening.

Even when the Japanese started to make huge inroads, they assumed it was because Japanese workers were more docile, that it was an easier environment for manufacturers. It took them a long time to decide, “All right, I guess we have to adopt this.”

Brett McKay: I think in the book you highlight there was this one particular GM factory. It was like the worst GM factory in America, but they brought in people from Toyota, and eventually, they turned this thing around. What happened there?

Robert Maurer: It’s an amazing story because I have heard interviews with the workers at Fremont. It was an originally a General Motors factory, and evidently, workers thought the management was so hostile, so harsh that the workers actually admitted they were sabotaging the cars. General Motors closed the factory down.

Well, as Toyota was starting and Honda was starting to make huge inroads, General Motors got desperate, and they took their design of the car and they took the same hostile workers back, and this time, they used Deming’s management methods including Kaizen, and at the same time, they were automating as many of their factories as they could.

Well, a year later, the highest quality cars in the entire General Motors line were the ones built with these workers in Fremont. I heard the same workers interviewed after Toyota took over, and some of them, believe it or not, would actually go to the show room, the dealer’s showrooms and watch people test drive the car. They had such pride in what they were doing.

It turned out it wasn’t the car, it wasn’t the labor problems. It would turn out it was the manufacturing process that gave people dignity and a sense of importance that Kaizen provided because what Kaizen asked each worker to do is to go to work each day thinking, what small step could I possibly take to improve the process of product? People went to work with a sense of creativity and empowerment that nobody vested them with ever, ever before.

Brett McKay: Speaking of how they were sabotaging the cars, I think they were leaving Whiskey bottles and door frames and things like that.

Robert Maurer: Yeah, imagine how angry these people were. It’s just hard to fathom knowing they were putting their jobs at risk, but they were that angry.

Brett McKay: Kaizen, it’s all about empowering people on the ground, making small, incremental changes. This goes against the grain what we think how change is done. In your experience with working with patients, working with doctors, and just working with other individuals in this behavior change, what are the big myths that people have about change both personally and in an organization?

Robert Maurer: Well, it’s a great question. The best answer is to go back and define the alternative to kaizen, because basically, what the Western notion of change is what we call innovation, which we define as taking the largest possible steps to accomplish a large goal. For many people and many organizations, that’s the only way they think of change. We’re going to bring in some consultants and the guidance of new programs, it’s going to cost a fortune to implement. If I want to lose weight, I’m going to go to the gym, get a trainer, go on a radical diet. We tend to think in terms of big problem and big solution.

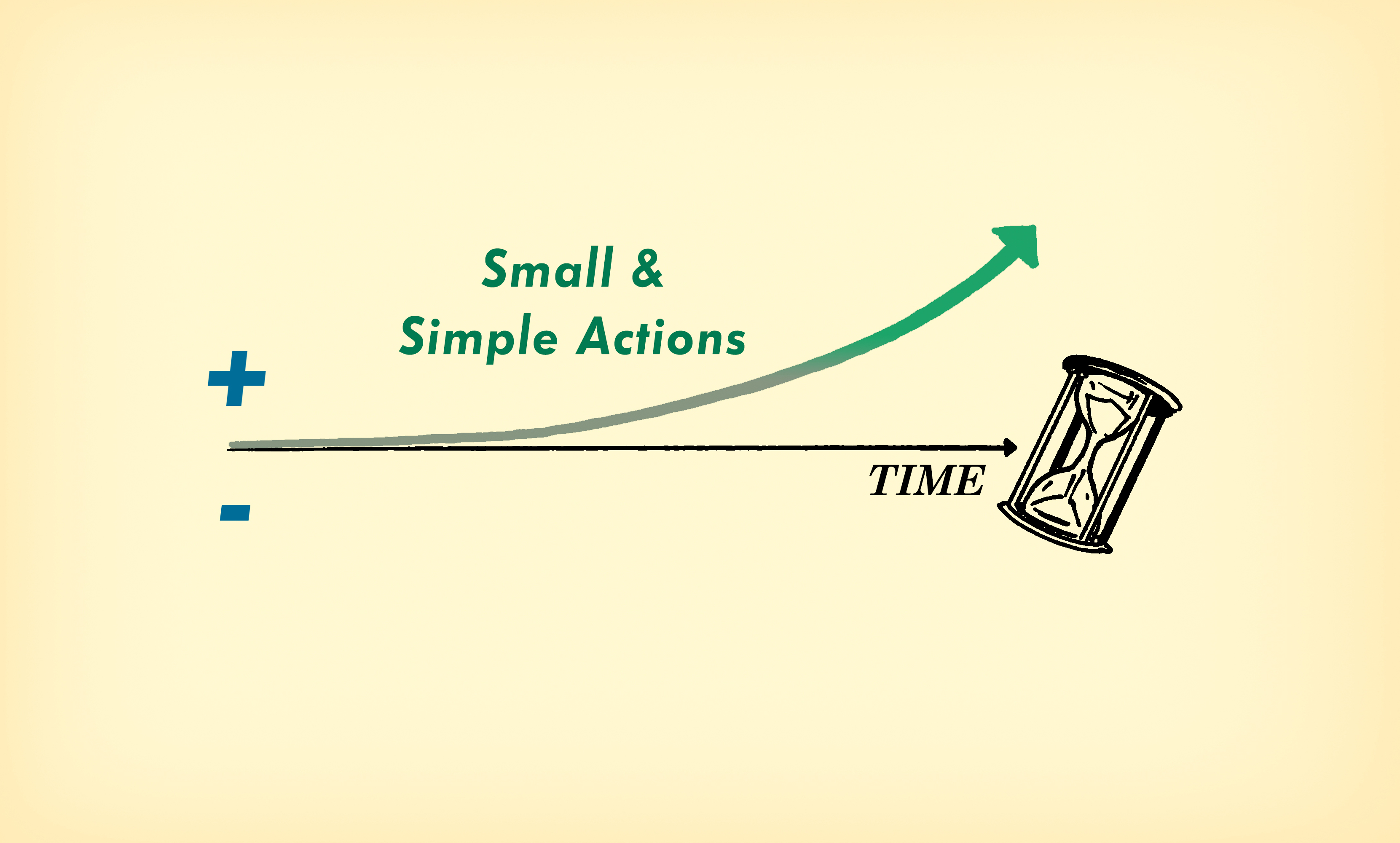

It goes completely against the Western mindset to think that we could get to the same goal, sometimes even faster with small steps as opposed to big, huge leaps, and as everyone listening to this has discovered, at some point in our lives, sometimes those big steps lead to big falls, and sometimes the price of that fall is more than we ever bargained to pay.

It isn’t that we’re trying to make innovation bad or wrong, but the question is, if it’s not practical or hasn’t worked, are you free to take very small steps to accomplish the same goal? The biggest myth, to go back to your question, is thinking that the, first of all, the only way to change is through big steps, and the second big myth is to think that basically, you’re trying to make it to decide am I going to take a, particularly in the creative process, am I going to take a small step or a big step because when you look at creativity, because one of our research projects, we looked at breakthrough products, everything from the Internet to the microwave to barcodes. So many great inventions came from some incredibly small inconsequential moment that somebody got intrigued with, and out of that small curiosity, breakthrough products came whether it’s Disney World or Disneyland, the credit card.

I could take you though any and all of those. They were all but some incredibly ridiculously small moment somebody thought, “Now, that’s interesting.”

Brett McKay: Yeah, it’s interesting. Like you said, we put this premium on innovation, and we think innovation just happens like, it’s sort of like this lighting bolt from the heavens, but as you say, really, most innovation, it’s very slow, and it’s the result of small steps until you got to that point.

Robert Maurer: Yeah, it’s the story we all grew up with, the children’s story of The Tortoise and the Hare. We just thought it was just a children’s story and not a metaphor for life.

Brett McKay: Besides manufacturing companies, I mean, how have you seen Kaizen being incorporated in the lives of regular folks? For example, with your work with doctors and helping patients live healthier lives. What are some of the success stories you’ve seen?

Robert Maurer: The value of the Kaizen, particularly in a medical setting is that you’re trying to get people to make life changes, and everybody that walks through the door of a clinic, and I’m sure everybody listening to this knows that we should exercise, we should eat well, we should get enough sleep, we should drink more water. This is not a mystery, but everybody’s got very good reasons why they don’t have the time, the energy, or it just seems overwhelming.

Getting somebody that’s got a job and children to raise or all kinds of responsibilities for elderly parents, any of those kinds of things will say, “You’re crazy. I don’t have, if I had time to do all that, I would,” but can you get someone to exercise one minute a day every day? Can you get somebody, for example, to … What happens, of course, is if you’re exercising a minute a day, after a while, what tends to happen is you develop a habit, and it starts to increase.

I remember years ago, before I ever met Dr. Deming and discovered Kaizen, there was a world-famous pain expert at UCLA giving a two-night course for people with cancer pain. At the end of the first night, he said to the group, “I want you all to go home and meditate for one minute.”

Well, I thought that was the dumbest idea I ever heard of, so I waited for the audience to leave, and as politely as I could, I asked the professor, “Why one minute? It’s not enough to do anybody any good.” He very patiently asked me, “How old is meditation?” I said, “Thousands of years old.” He said, “That’s absolutely correct. There’s a very good chance everybody in this room has heard of meditation before tonight. Those who like the idea have already found a book or a teacher and they’re doing it. For the rest of the people in this room, meditation’s the worst idea they ever heard of. I’d rather them go home and meditate for one minute then not meditate for 30. They may discover they like it. They may forget to stop,” which is what all the current research on Kaizen argues.

If you can get people to put a toe in the water to start something, it’ll eventually become a habit. We’d like people to drink more water, so getting people just to put a bottle of water at their desk, another in their car, another where they shave or put on their makeup, and you’re developing a pattern because the good news is, the brain’s a creature of habit. The bad news is, the brain’s a creature of habit. Anything you do regularly, the brain starts to commit cells to.

Simplest example I can think of is advertising. If you draw two golden arches and ask people what it is, they’ll say McDonald’s, and some of these people have never stepped foot in one of their restaurants, but they’ve seen those 15-second commercials over and over and over again, and so they can tell you three or four of the products of a restaurant they’ve never been into. Advertisers know repetition is what the brain decides is important, so if you can get people to do something just momentarily, just for 15 seconds, 20 seconds, a minute, you can get people to make changes.

There’s a wonderful Kaizen technique called mind sculpture. There’s a book by that name that takes people through the technical parts of it. My book talks about the applications of it. What it is, they discovered in some athletes would had injured themselves and who recovered much faster than anybody dreamed, they were using this technique called mind sculpture. You can use it for sports, you can use it for public speaking, you can use it if you’re afraid to go out on a date, you can even use it to exercise.

It’s based on the premise that if you close your eyes, imagine yourself, for example, in the gym, picturing reaching down to lift the weights, and again, you’re not moving a muscle, you can feel the muscles in your arms start to tense, you can feel your breathing increase. Again, in retrospect, based on a simple principle with your eyes closed, your brain is so stupid, it doesn’t know where it is, and it’s sending perfect messages to the body.

If I’m afraid of public speaking and I close my eyes, picture myself in a classroom with 30 students, half of them on their smartphones, 25% of them still sleeping, but I imagine what I’d say, voice, tone, gestures, just 15, 20, 30 seconds at the most at a time, one, two, three times a day at most, again, eventually, the brain decides this is important and commits cells to it.

You can do something just a few seconds at a time like you do watching commercials, and eventually, the brain decides this is important and commits the body to it. It’s a wonderful technique for people that would like to make changes but have close to no motivation at all because mind sculpture takes almost no time.

According to the research in his book, if you’re doing that with exercise, I’ll actually do it on an airplane. Close my eyes and imagine I’m in the gym running, and according to the data, you’re burning 25% of the calories you’d actually burn in realtime, and the brain’s practicing doing it perfectly.

Brett McKay: Basically, you take any task that you’re feeling overwhelmed by, you’re putting off, and just mentally rehearsing you’re doing it.

Robert Maurer: Yeah.

Brett McKay: I guess the trick is to get as vivid as possible with it?

Robert Maurer: Yes, as much as you can. Again, your inner visions are never as clear as the outside ones. The book starts off with a very famous British javelin Olympic athlete who had injured his shoulders a few months before the Olympics, was obviously, had his arm in a tourniquet, but imagined himself in the Olympic stadium reaching for the javelin and picking it up and throwing it again while he was, his shoulder and arm was immobile, and went on to win a medal, just because he, again, practiced it perfectly.

Some of the Olympic ski teams spend half their time practicing in a classroom going down the mountain in their mind because again, the muscles are practicing doing it right instead of practicing falling.

Brett McKay: That’s an easy first step, just thinking about doing the thing and visualizing it, not just thinking about it. Yeah, visualizing it is key.

Let’s look at some more other brass-tack things that people can do with Kaizen. Like you said, a lot of this stuff, it’s going to seem like guy who said just meditate for a minute, and you’re like, “How is this going to work.” In the book, you talk about one of the first steps is to ask small questions. What do you mean by, I mean, what are some examples of small questions in trying to apply Kaizen to a task?

Robert Maurer: That one, I stole from Deming and Toyota because as Toyota was rebuilding out to the war, Deming simply asked each of the Toyota workers to ask themselves a question. The question was what small trivial step could I take that may improve the process or product? What Deming suspected and we still believe to be true, though nobody knows why is the brain cannot reject the question. Any question you ask repeatedly, the brain’s compelled to pay attention to and start its own Google search. It’s a really bizarre finding about the brain.

If I’m doing a five-day program staying at a hotel for a group, and I’ll say to them first day, “What color car’s parked three cars to the right of yours in the parking lot?” They look at me like that’s the dumbest question I ever heard, only of course, it is. I ask them the same stupid question on Tuesday. By Wednesday at the earliest, Brett, Thursday at the latest, going into the parking lot with far more interesting things on their mind, a place in the brain with a funny name of hippocampus will say to them, “That fool’s going to ask me again about the color of the car,” and they’re forced to store an answer in short-term memory. The brain cannot reject the question.

The trick is that the question has to be small enough that it doesn’t make the person afraid. If the question I ask is, “How can I be thin by the end of the month?” “How am I going to get married by the end of the year?” “How am I going to make a fortune in the next six months?” the bigger the question, the more it triggers fear in the brain and it overwhelms the creative process.

If you make the question small and trivial but ask it each day, whether it’s what activity would make me more joyful in life or what it is I could do in the next week or so that would make me more productive, just asking the question patiently once or twice a day, and the brain takes on the Google search. As every one of your listeners can probably attest, all of us have had the experience where you’re in the shower, you’re driving to work, and all to a sudden, you got a solution to a problem because the brain percolated on it and eventually, in its own inefficient but magnificent way, solved the problem.

Brett McKay: That’s great. Let’s give some specific examples here. Let’s say someone is trying to pay off their student loans, and I guess the wrong question would be, “How can I pay off my student loans by the end of the year?”

Robert Maurer: Again, we’re not trying to make innovation bad or wrong. You could ask the question, and then all of a sudden, you get a great answer, that’s fantastic. Most of us get stuck and overwhelmed by the question, which is what you’re suggesting.

The alternative would be, “What small step could I take today that could save me some money whether it’s instead of getting Starbucks, going to 7-Eleven for coffee, whether it’s taking a bike instead of the bus.” Any small way you can begin to reduce your financial expenditures.

Now, you think, “Well, I only got $30,000 in debt, and you want me just to save $2 on cup of coffee?” You’re right. It’s not going to, it’ll take you two generations to pay off the debt, but you’re training the brain to start to look for ways to save money, and so you’re programming the brain for a process you want it to engage in. That would be one way to deal with.

Another, using that same example, just asking the question, “Who can I ask that could help me find ways to manage this debt any more creatively?” Just asking the question once a day, and eventually, you may find yourself looking at government agencies, looking at different programs because there’s a dozen different programs to help student debt get resolved, but the idea of sitting there spending two hours on the Internet could be overwhelming to people. The idea of just asking the question and letting the brain percolate on it may be a much easier and more acceptable strategy.

Brett McKay: Right, so you’re basically trying to kickstart your brain into thinking small with these small questions, and when those will sort of, it’ll snowball eventually.

The question, I thought this is a great opportunity to use Kaizen with other people, like say you’re a manager or even a parent, this would be a great opportunity, like questions are a great way to help others implement Kaizen in their own life. It’s a good coaching opportunity.

Robert Maurer: Yes, exactly. In fact, I was watching an interview on a TV show with Yo-Yo Ma, the most famous cellist and one of the most famous musicians in the world, and he was talking about the fact his father set very high standards, but each day, very, very small steps that he could accomplish.

The idea of creating small victories allows the team to develop, allows confidence to develop. The other thing about small steps, particularly in the workplace, is you don’t know which small step is going to turn out to be huge. As I said, there’s so many breakthrough products, from the credit card to Disneyland that turned, there was some small moment that the laser and that nobody thought was going to turn out to be because you don’t know when you take a small step what’s going to end up staying small and what’s going to become huge.

Brett McKay: Yeah, I was thinking this would be my kids, like whenever they get frustrated, instead of trying to figure it out for themselves, like instead of doing it for them, it’s like, ask them a stupid small question and help them solve their own problem.

We talked about mind sculptures. That’s basically thinking very small thoughts, and again, people might think, “How’s just visualizing me doing the task going to help,” but as you said, it can help a lot, but then after thinking small thoughts and using this visualization practice, which doesn’t take hardly any time at all, you can do it while you’re on the airplane, but you gotta take small actions.

I mean, how small are we talking here. I mean, is it literally a minute of meditation small where that’s not going to, like we’re going to think, like basically, is that the threshold, that’s not going to do anything. Is that when you know you’ve gotten small enough?

Robert Maurer: The criteria for the smallness is the step that’s so ridiculously small that it requires no willpower, self-control, or discipline, that there’s not going to be any pushback. That’s how you know it’s a small enough step.

A lot of it’s in the mind of the beholder, so for some people, they hate exercise, feel overwhelmed by their life. If they can exercise, if they can stand in front of the TV during one commercial, or at least the 60 seconds that the commercials run and just walk in place as fast as they can during one commercial or during two commercials, whatever’s doable, then eventually, they start to develop … If you talk to anybody who exercises, they, initially, they hated it, then they tolerate it, now they miss it if they don’t do it. You’re trying to develop a habit, and you do that a minute at a time.

My favorite example was done in Pittsburgh, and then it was done in Ireland where they went to a huge high rise building, went to the sixth floor, and people who said they hadn’t exercised since high school, said, “Congratulations. Christmases come early. Here is a lifetime gift certificate to the health club across the street, a gift certificate for your trainer for a year.”

Went to the 12th floor of the same building, another dozen people in a different firm that hadn’t exercised since high school, only asked them to do on Monday was to go in in a stairwell, go up one flight of stairs back to their floor, back to their desk, back to work. Tuesday, go in the stairwell, go up one flight, add a single step, back to their floor, back to their desk, back to work. Wednesday, two steps, you get the idea. Every day of the work week, getting one step, this ridiculous regimen, but come back one year, three years, five years later, which of those two groups do you think is exercising better with better cardiovascular fitness, lower cholesterol, lower weight? The people at the health club or the steppers? Of course, the answer to that, I think, is pretty obvious, the steppers.

If you can get people to do whatever it is they’re resistant to for whatever number of minutes, they are sure they can do it because it requires no conscious effort on their part, and then eventually, the brain develop a habit for it.

There’s research out of Texas showing if you exercise three minutes a time 10 times a day, you get most, not all, the same cardiac benefit you would get from exercising 30 minutes. Of course, it’s a lot easier to find three minutes at work to take a quick walk around the block or go up two flights of stairs than it is to go to the gym for a half hour in the middle of a work day.

Brett McKay: That’s crazy, and some, yeah, you can use this for paying off debt, so it’s like, I’m going to save a dollar today. Have you seen this used, the small step used to help people quit smoking in your work?

Robert Maurer: Yes. Yeah, for some people, innovation’s the answer is smoking because I just saw a person this morning that woke up one day and decided to quit, and she’s now 30 days without smoking. Now, that looks like innovation but it’s deceptive because if you ask her how long have you been thinking about quitting, it’s been a slow, incremental process of contemplating, consideration, discussion, and debate but in her mind before that faithful day when people made the leap into innovation.

Sometimes, the steps … I’m sorry, I lost your question, but sometimes, the small steps lead to big ones that the person hadn’t even anticipated. But I think I lost your question, Brett, sorry.

Brett McKay: No, yeah, that’s fine. No, you were talking about smoking, like using small steps to quit smoking.

Robert Maurer: Oh, smoking. Yeah, yeah, yeah. Sometimes, innovation, in fact, when you look at the research, cold turkey, the person just got up that day and quit, it looks like innovation, but in fact, it’s usually something the person contemplated for weeks, months, or years before that faithful day.

The other way Kaizen’s used for smoking, cut the cigarette down or you just, you only smoke half of it or … One of the big problems for people who have trouble quitting is that they need a cigarette the moment they get up in the morning, and so you ask them if they’re willing to either take a shower first, have a cup of coffee first, wait another 30 seconds or a minute before they have that first cigarette, because all of the most successful habit-breaking techniques for smoking involve making small changes.

Instead of having the cigarette in your car, can you stand outside the car? Can you have the coffee without the cigarette? Just trying to break the patterns that smoking’s associated with. Get rid of the ashtrays in your house, those kinds of things. Anything that breaks up the habit of having associating the cigarette either with certain friends or with coffee or with car or whatever. Those are some of the ways we can use Kaizen for cigarettes, particularly in people that are really struggling with it.

Brett McKay: In the book, you give other great examples of habits that people, I’m sure a lot of people have tried starting their own life, but if you apply Kaizen to it, your success rate will go up significantly, like journal writing. A lot of people are like, “I’m going to write in my journal every day,” and they think they have to write for 30 minutes, but you said, “No, just write for a minute and then add a minute every week or so.”

Robert Maurer: Yes. In fact, I can give you a personal example because when I got the contract to write this book, I do not like to write, it’s one of my least favorite things to do on the planet, and so I thought, well, let’s see if Kaizen works. The contract gave me a year to write the book, and so I said, “I’m going to just write, all I’m promising to do is to write 60 seconds a day. That’s it,” and so I’ve done that, it’s a success. Of course, like with the meditation the UCLA professor, originally, I just kept to my agreement that eventually, of course, I forgot to stop, and that’s what you’re counting on with Kaizen. You’re building a habit.

The other way Kaizen works, Brett, is that you’re programming the brain to the leap that you want it to make. Let me give you a simple example. If I had a room full of people and I said, “How many of you remember the exact instant when you mastered driving?” Nobody raises their hand. We all remember lurking through a grocery store parking lot with this car we could barely control, and yet, at some point, you’re driving down the highway, completely absorbed by the conversation with your passenger or by the conversation on the radio, completely oblivious to the fact the brain is now making very complex life-saving decisions moment by moment while we’re behind the wheel of car. The brain learned it incrementally and made the leap into innovation on its own.

Again, there’s a artificial distinction Kaizen and innovation. Even big steps usually are preceded by many small ones.

Brett McKay: Also kind of coupled with small action. You also encourage reinforcing these actions with small rewards. How would that look on a practical level?

Robert Maurer: Sometimes people think, “When I lose all this weight, I’m going to go out and buy a new wardrobe and I’m going to do this and do that.” If you can find some very small way to reward yourself, again, usually not with food unless that’s not an issue for you, even if it’s just calling up a friend who’s going to say, “Great work,” or calling up somebody to brag, anything positive that you’re going to alow yourself to do at the same time or afterwards.

One of the ways I got myself to floss because flossing’s one of the most useful things you can do for your health. It actually helps prevent heart disease, believe it or not, but I just never had time for it, so what I would do is I put the floss right on top of the remote control so that while I was watching TV I could floss. If you can associate something you don’t want to do with something you love, then it tends to be easier. Maybe that’s why all these new gyms have fancy TVs in front of the treadmills so that you can do something you love while you’re doing something you just assume not have to do.

Brett McKay: I think that’s called, there was a paper, I think, write about, it’s like temptation bundling is what it’s called. I think I’ve heard it referred to as that.

Robert Maurer: In business, one of the things that we now have enormous research on is that giving big rewards for big suggestions turns out to be a bad idea. The average award in a US car factory if you make a big suggestion is over $400. In Toyota, it’s $3.

Now, the difference is people have to feel they’re being paid fairly for their labors or all bets are off, but if you think there’s a big reward, what are you looking for? You want the big reward, and for $450, am I going to share it with the three people standing next to me on the assembly line? Not very likely. They found that small amounts, $3 or less, and you get on the average of a hundred more suggestions from an employee than if you’re offering them $400, but again, they have to feel they’re being paid fairly.

Brett McKay: We’ve been talking using Kaizen to solve big problems. It’s like going back to that Chinese phrase, journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step, but you also talk about, you can use Kaizen in a way, instead of solving big problems using Kaizen, using Kaizen to find small problems that you can fix that will provide a big payoff in your life. Any examples of that?

Robert Maurer: Yes, because when you look at so many breakthrough products that they turned out to be some small frustration that other people just endured, this person got intrigued with. We got the credit card from two New York City attorneys who were out to dinner arguing about the check until they both realized they didn’t have any money. Fortunately, one of them lived a few blocks from the restaurant, called his wife, she came down with some cash, on the walk back to the apartment, the two of them remembered that moment’s embarrassment in the restaurant and thought, “Well, there has to be an easier way to pay for restaurant bills and diners club.” Our first credit card was invented that night.

The story’s going around about Uber and Airbnb are about people who, again, had just a small idea. Airbnb’s story’s been told many times that these two guys who were just about to lose their apartment. There was a big convention in San Francisco, there was a shortage of rooms, so they put a list on Craigslist just to rent out their air mattresses, which is how they got their name, and that led to Airbnb.

We got barcodes from a guy that was trying to figure out how to help grocery stores with their checkout process. Couldn’t figure out what to do. One day, in complete frustration, he goes off to the beach, sticking his hand in the sand in frustration, took his hand out, saw the sand sticking to the grooves on his fingers and thought, “That’s it,” and barcodes were invented that day.

There’s so many breakthrough products and ideas come from some momentary frustration or annoyance or irritations, somebody thought, “You know what? I think there’s an idea here on how to make it better.”

Brett McKay: Look for those small annoyances in your life and fix them, and you’d be surprised how much that will improve your life, just getting rid of those annoyances.

Robert Maurer: Exactly, and it may turn out to be something that the rest of the world’s interested in too.

Brett McKay: Right, right. An example from my father-in-law, the garbage can in their house was under the sink, where a lot of people keep their garbage can, but it was annoying because the garbage can didn’t come out, so you throw stuff in there but sometimes it wouldn’t make it, and so you’d have to dig in the back to find the trash that didn’t make it to the garbage can.

He decided, like make this pull-out thing that he puts the garbage on, and so you pull the garbage can out, throw it away, then push it back in. It’s just like, it’s been, it was a big improvement in his life. It was a daily annoyance of his, and he fixed it. It took like 20 minutes. It might seem stupid and insignificant, but it’s an example of a little thing that can improve your life significantly.

Robert Maurer: Yes, and sometimes, again, sometimes those things lead to products that the world’s waiting for too. They just didn’t know they were waiting for it.

Brett McKay: Right. As you do this Kaizen process, you build up this habit, you’re building of habit. You’re creating this new groove in your brain. Does this carry over into other, does it transfer over to other domains of your life? Say if you use Kaizen to, I don’t know, start exercising regularly, will that allow you to take on other challenges easier because you’ve developed that ability, that Kaizen process within you?

Robert Maurer: That’s what all the research argues. The obvious example is the one you gave where if you start exercising, all of a sudden you’re thinking twice before having that second donut because you’re going to have to drag that extra weight around when you go around the block tomorrow.

Exercise tends to increase your interest in taking better care of yourself in other areas. Yeah, it does work in a couple of ways, but one of them, we think, is once you start having small victories, you then start wanting to have more small victories, which lead you to look for other places in your life where you can make small changes. Just starting to throw away the first two bites of the donut and eating the rest of it, eventually, what you’re training the brain is, I don’t have to eat everything I see.

Now the thing that makes Kaizen hard is that many of us, myself included, we tend to make changes when we made a mistake in life. It’s those decade birthdays when you think about, “Oh my gosh, I wish I had spent more time doing whatever,” or your doctor scares you with diagnosis or a relationship ends, and many of us, at that point, are pretty angry with ourselves that we’ve done something foolish, and then when you’re angry at yourself, it’s hard to think about small steps. You want to correct the problem yesterday so this voice in your head will stop telling you what a loser you are.

In addition to kind of a cultural focus on innovation, it’s hard for some people to adopt Kaizen because they’re so angry at themselves. They’re desperate for improvement.

Brett McKay: I think the other hard part about Kaizen is that it can be, it’s so easy that you don’t believe it’s going to work.

Robert Maurer: Exactly. Yup, and that’s why I wrote the book was that people could see all the research on it, but you’re right, it defies common sense. Doesn’t seem logical or possible to accomplish in small steps what a big leap would.

Brett McKay: Well, Robert, this has been a great conversation. Where can people go to learn more about the book and your work?

Robert Maurer: There’s a website, scienceofexcellence.com, which has a lot of the research that we’ve been talking about and the book on Kaizen that you’ve been referencing, One Small Step Can Change Your Life. There’s also a second book on how to apply Kaizen in the workplace called The Spirit of Kaizen, and my latest book is about what makes Kaizen so powerful, and that is it is kind of a quiets the fear of mechanism in the brain, so the third book is called Mastering Fear.

Brett McKay: Fantastic. We’ll make sure to link to those in the show notes. Robert, thank you so much for your time. It’s been an absolute pleasure.

Robert Maurer: The same for me. I appreciate your questions very much.

Brett McKay: My guest today Robert Maurer. He’s the author of the book One Small Step Can Change Your Life: The Kaizen Way. It’s available on amazon.com. Also, check out his website at scienceofexcellence.com where you can find more information about his research and work and find more information about the other books he’s published.

Also, check out our show notes at aom.is/kizen, where you can find links to resources, where you can delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another edition of the Art of Manliness podcast. For more manly tips and advice, make sure to check out the Art of Manliness website at artofmanliness.com. If you enjoy this show, got something out of it while you’ve been listening to it, I’d appreciate it if you take one minute to give us a review on iTunes, Stitcher, or whatever it is you use to listen to podcast, or tell a few friends. I’d appreciate that as well. Helps us out a lot. As always, thank you for your continued support. Until next time, this is Brett McKay telling you to stay manly.