By now you’ve probably heard about the well-publicized research pointing to the extraordinary benefits of spending time in nature. “Vitamin N” has been shown to decrease stress, ward off depression, reduce obesity, boost the immune system, and enhance cognitive abilities.

You may have even heard that these same frustration-calming, focus-improving, mood-lifting, health-supporting benefits apply to children too. Spending time in nature has even been shown to alleviate the symptoms of ADHD. And beyond these more concrete effects, children who regularly spend time in the outdoors report feelings of greater peace, freedom, confidence, mystery, wonder, awe, and joy.

Really, the effects of nature are such an enormous boon to physical, emotional, and mental health that were they offered in the form of a pill, people would be rushing out to buy it for themselves, and their children, even if it was exorbitantly priced. And nature is free!

Yet, many adults don’t spend very much time outdoors, and neither do their kids. Children in fact spend half the time outside as their parents did growing up. Some studies say they only spend about a half hour outside each day, while others put the number as low as 4-7 minutes; either way, today’s kids are spending less time outside than inmates do at maximum security prisons. This, despite the fact that 96% of parents surveyed want their children to spend more time in the outdoors and think a connection to nature is important for their development.

What accounts for this disconnect?

The rise of technology is certainly a factor; children ages 8-18 now spend over 7 hours a day looking at screens. And despite what parents say to the contrary, many moms and dads actually prefer keeping their children indoors, worried as they often are these days about their kids being kidnapped or hurting themselves.

But there’s also another factor at work. Many people today have an all-or-nothing approach to experiences; if something isn’t “perfect,” and wholly “authentic,” it’s not worth doing at all. This attitude shows up in parents’ failure to get kids outside: they feel like nature is something “out there” — something far away and a little inaccessible. Nature seems like something you can only find at state or national parks, places that require a lot of planning, preparation, time, and hassle to get to. Consequently, busy modern parents, who live in cities or suburbs and often already feel overwhelmed in keeping up the normal work/life balance, don’t feel like regularly getting their kids into nature is a doable goal.

Fortunately, with a simple mindset change, and a new paradigm through which to approach things, it’s possible to greatly enhance your children’s connection to the outdoors, and to do so much closer to home, and with more ease than you think.

Follow the Nature Connection Pyramid to Easily Ensure Your Kids Get a Healthy Diet of the Outdoors

In Last Child in the Woods, Richard Louv encourages parents to stop thinking about getting their kids into nature as a leisure time indulgence or as one recreational choice among many equally good options. Given the benefits that accrue from time spent outdoors, he instead encourages parents to see contact with nature as just as essential to their children’s health as sleep and nutrition.

The parallels between time spent in nature and diet are particularly apropos, in that the optimal “servings” for each lend themselves to being organized into a pyramidal shape.

Studies show that the more immersed in nature you get, the more its physical and mental health benefits work their magic. But research also shows that even minimal contact with nature, like simply looking at it through a window, produces some positive effects as well. So rather than looking at increasing your children’s contact with nature as an all-of-nothing equation, it’s much better to think of it as a spectrum, in which experiencing an abundance at the lower end is just as nourishing as getting a little at the higher end.

Kenny Ballentine, head of the Nature Kids Institute, created the “Nature Connection Pyramid,” as a great way to visually understand this idea. The pyramid doesn’t scale from the bottom up in terms of “bad” or “good,” but rather shows how to balance out the servings of nature your kids get on a daily, weekly, monthly, and yearly basis.

As you can see, trips to true wilderness do not constitute the only way to give children an ample dose of Vitamin N, and in fact sit at the smallest part of the pyramid; while these time and preparation intensive outings are certainly worthwhile, you need not feel pressure to make them the foundation of your family’s “nature diet.”

Instead, the biggest bulk of your family’s servings of nature can be made up of daily, weekly, and monthly outings that are pretty simple to plan and execute. Rather than making the perfect the enemy of the good, you simply need to aim for the (near) perfect at least once a year, and “settle” for making the good (which often turns out great) a regular part of your children’s lives.

Below we riff on the Nature Connection Pyramid, offering advice from leaders in the work of getting kids outdoors, as well as tips from what’s worked for our own family in getting more nature on a daily, weekly, monthly, and yearly basis.

The Foundation: Passive and/or One-Time Decisions That Can Increase Your Children’s Contact With Nature

Before we get to the first level of the pyramid, let’s talk about the foundation this “structure” rests on. There are several one-time decisions you can make that will increase your children’s contact with nature ever after.

Now, keep in mind that these ways to connect with nature are on the part of the spectrum farthest from real wilderness immersion. But compared to how relatively passive and “un-wild” they are, they can have outsized effects in the lives of your children.

When buying a house, consider its natural surroundings. As mentioned briefly above, research has shown that even simply looking at nature through a window creates salubrious effects in the viewer. For example, patients in hospital rooms that had windows overlooking a grove of trees were shown to recover faster from surgery, and needed less pain medication, than those whose windows faced an exterior wall. Conversely, prison inmates with cells that faced an interior jail yard got sick 24% more often than those with windows overlooking farmland. In a study done in an office environment, employees with windows that furnished views of bushes, trees, or lawns, experienced less frustration and were happier on the job than those without.

These results have been duplicated in children. When a study looked at the degree to which nature surrounded children’s homes (an assessment which included the amount of nature seen through windows, and whether they had a grass, concrete, or dirt yard), they found that the more natural the surroundings, the better the children’s psychological well-being and ability to deal with psychological distress. “Our data also suggest little ceiling effect with respect to the benefits of exposure to the nature environment,” the researchers further noted. “Even in a rural setting with a relative abundance of green landscape, more appears to be better when it comes to bolstering children’s resilience against stress or adversity.”

So while it’s not always possible to live somewhere bucolic, when deciding between where to settle down, and between one house and another, consider how “nature-filled” the yard is, and how much nature you can see through the windows when indoors. This is something to keep in mind even if you live in the city. When a study looked at two otherwise equal low-income high-rise apartment buildings in Chicago, the residents of the one with stands of trees nearby reported lower levels of aggression, violence, and crime, as well as greater psychological resilience, than the building surrounded only by concrete.

If you live in a house for 10 years, that’s 3,650 days your kid is going to stare out the windows after having a hard day, when doing homework, and while thinking about the future. The day-to-day view out those windows is going to have a far greater effect than a yearly trip to Yosemite. All without you making further effort after signing the mortgage (beyond the monthly payment!).

If you’re already settled in a house, find ways to bring a little more into nature into your yard. Plant more vegetation and trees and/or start a garden. You might also consider the following:

Attract wildlife to your yard by installing bird/bat houses, bird baths, and feeders, and planting certain trees/flowers/shrubs. If you’d like your yard to be a more diverse ecosystem, with various creatures to spy out, there’s a variety of things you can do. If you want to attract birds, offer them a nesting box or feeder. Or set up a bat house to welcome our nocturnal friends (they’ll eat your ‘squitos!). Create a little pond that can be luxuriated in by frogs. There are also various flowers, bushes, and trees you can plant to increase visitations from butterflies and small animals. Specific ideas are just a google search away, or look over a general list of ideas like this one.

Consider getting plants and/or a pet. If “re-wilding” your backyard isn’t an option (or you don’t have a yard, period), consider bringing some flora and fauna inside.

The positive effects of contact with nature don’t just arise from looking at it through a windowpane, but even from hanging out with it in the form of a house plant! One study that looked at hospital patients found that those with greenery in their rooms had significantly lower blood pressure, anxiety, heart rate, and pain than those who did not. And in the study mentioned above that showed a link between the amount of natural surroundings in/around a home and children’s resilience, one of the factors the researchers included in their assessment of a house’s level of nature was the presence of plants indoors. Putting a few plants around your house can make it feel like a calmer and more restorative oasis.

Pets can have a similarly calming effect, and have been shown to lower blood pressure and reduce stress. Fido isn’t really a wild animal, but he does bring a bit of non-human nature into your home. Plus, if you make the kids walk the dog, it gets them outside!

Don’t get a car with backseat televisions (or let your kids watch tablets on shorter drives). At the risk of inducing the ire of their fans, I hate backseat televisions. Maintaining the strength of your kids’ attention spans is hard enough these days without making your vehicle another hotspot for non-stop stimulation. Not to mention that in watching these screens, whether built into the seats, or in the form of hand-held tablets, kids miss out on looking at nature through their window, which as we’ve abundantly explained, is actually a really beneficial activity!

Children not only absorb nature’s health-ifying vibes while staring out the car window, they also get a better understanding of the lay of the land — of their community, and country. As Louv puts it:

“The highway’s edges may not be postcard perfect. But for a century, children’s early understanding of how cities and nature fit together was gained from the backseat: the empty farmhouse at the edge of the subdivision; the variety of architecture, here and there; the woods and fields and water beyond the seamy edges — all that was and is still available to the eye.”

Now I’m not an absolute Luddite or purist in this matter. On a long road trip, I’m perfectly okay with allowing my kids to watch a movie sandwiched between tech-free stretches of time. But for shorter rides — I’d say anything less than 3 hours — they ought to have a chance to think about nothing, and look out the window to watch the world, and different kinds of nature, go by.

Daily

Let’s now begin to work our way up the levels of the Nature Connection pyramid, starting first with those things you can do daily to give you children greater contact with the outdoors. This needn’t involve any macro maneuvers; while we grown-ups need a bigger “hit” of nature to be impressed, as Louv puts it, “Expeditions to the mountains or national parks often pale, in a child’s eyes, in comparison with the mysteries of the ravine at the end of the cul de sac.” There’s plenty for your kids to explore in your neighborhood and even your own backyard. Getting them out there is really just a matter of you willfully unlatching the door, and creating firm nudges towards it.

As Scott D. Sampson puts it in How to Raise a Wild Child, the goal is to simply “establish nature as the fun and preferred option for playtime.”

Let your kids play outside by themselves. Yeah, I know, this is beyond obvious. But for a whole bunch of reasons we discussed in-depth earlier this year, parents are often afraid to let their kids play outside alone these days: they’re worried their children will be kidnapped or hit by a car (even though the rates of crime and traffic accidents are both down), or will be traumatized by injuring themselves (even though research shows that getting hurt is actually good for building the resilience of a child’s psyche).

In trying to mitigate these inflated risks, other risks pop up in their place, like the risk of an overly protected child failing to develop autonomy, confidence, and competence. To these general risks, let us also add those specific to being deprived of the benefits that come from playing in the outdoors without parental supervision. Children who play by themselves in nature (rather than on a structured playground) are more physically active, play more imaginatively (including being more likely to invent their own games) and for longer stretches of time, gain greater motor skills and physical agility, increase their ability to concentrate, and show a greater sense of wonder.

That’s a lot to make kids give up, when keeping them indoors barely increases their safety, if at all. So yes, let them play outside! If you have trouble letting go, we’ve written a whole guide to doing it as painlessly (and safely) as possible.

Let your kids get dirty. While you may worry that playing in the dirt will make your kid sick, it’s likely to have the very opposite effect. According to the “hygiene hypothesis” our super zealous desire to live sanitized, scrubbed-clean lives may actually increase our susceptibility to allergy and inflammatory disorders. Tiny microbes present in soil and other organic matter are in fact good for the immune system, and there’s further evidence that getting down in the dirt lowers stress levels and increases attention span.

Of course, you (or more likely, your wife) may not be crazy about your kids playing in the dirt and mud, less out of fear of their getting sick, and more out of the worry that they’ll ruin their shoes and clothes. To allay this anxiety, designate some old outfits as their “get-as-dirty-as-you like” duds and also invest in a pair of Croc-type boots your kids can wear in puddles and mud.

We have a drainage ditch in the backyard that turns into a little stream after a heavy rain. After Gus and Scout put on their boots and crap clothes, it’s easy to give them the parental greenlight to go crazy in the “creek.”

Start a “natural history museum.” When Theodore Roosevelt was a boy, he had a keen interest in natural history and the flora and fauna around him. He not only read books on the subject, but collected specimens himself and wrote works of his own, filled with detailed observations. Sometimes he pocketed an animal he already found dead, sometimes he brought live critters — including mice, frogs, snakes, and a snapping turtle — home with him, and sometimes he hunted, and then taxidermied, his own game. Altogether, by the time he was 11 years old, his bedroom was filled with 1,000 living and stuffed specimens — a collection he dubbed “The Roosevelt Natural History Museum.”

You don’t have to let you kids go quite as far as TR (even the members of his understanding household eventually got tired of the smell of critters and taxidermy chemicals, as well as finding snakes in their water pitchers). But you can encourage your children to start a more modest “natural history museum” of their own; Sampson advises setting aside a “nature table” for the purposes of “housing” this collection:

“Consider putting aside a table for kids to bring in their latest discoveries. Rocks, sticks, pinecones, and bones are all fair game. You might even encourage the collection of live critters — bugs and lizards, for example — to be kept temporarily in clear containers (with air holes added, of course) before being released. A further step, if your comfort level allows, is a terrarium, often made from a recycled aquarium with a lid added. Terrariums allow kids to care for animals and watch them for extended periods. At least a portion of the objects in this mini-zoo can be changed out on an ongoing basis, as new finds arrive. The beauty of a nature table is that it can be something your child is proud to curate.”

Read books with a nature-themed backdrop or plot. Having your children read (or reading to them) books that incorporate nature in some way can spur their imagination and interest in the outdoors. These don’t necessarily have to be non-fiction, or even realistic fiction; even fantastical nature settings — like those found in The Hobbit or the Narnia series, for example — can increase the magic and allure of nature for kids. C.S. Lewis explained the effect of such stories on a child:

“Fairy land arouses a longing for he knows not what. It stirs and troubles him (to his life-long enrichment) with the dim sense of something beyond his reach and, far from dulling or emptying the actual world, gives it a new dimension of depth. He does not despise real woods because he has read of enchanted woods: the reading makes all real woods a little enchanted.”

Weekly

With activities you’re only going to do once a week, you can afford to be slightly more ambitious with your outings, and leave your literal backyard for your metaphorical one — the local parks about town.

Even though every family is busy, every family, if they took an honest look at their schedule, has a small block of time on the weekend or after school to take an outing that only requires a couple hours. If you find you have good intentions in this area, but trouble following through on them, I would suggest taking an 8-week microadventure challenge. And if simply declaring that challenge to your family still doesn’t motivate you enough, then I’d recommend taking part in the 12-week Strenuous Life Challenge, and making the Microadventure Badge the one badge you must earn to successfully complete it.

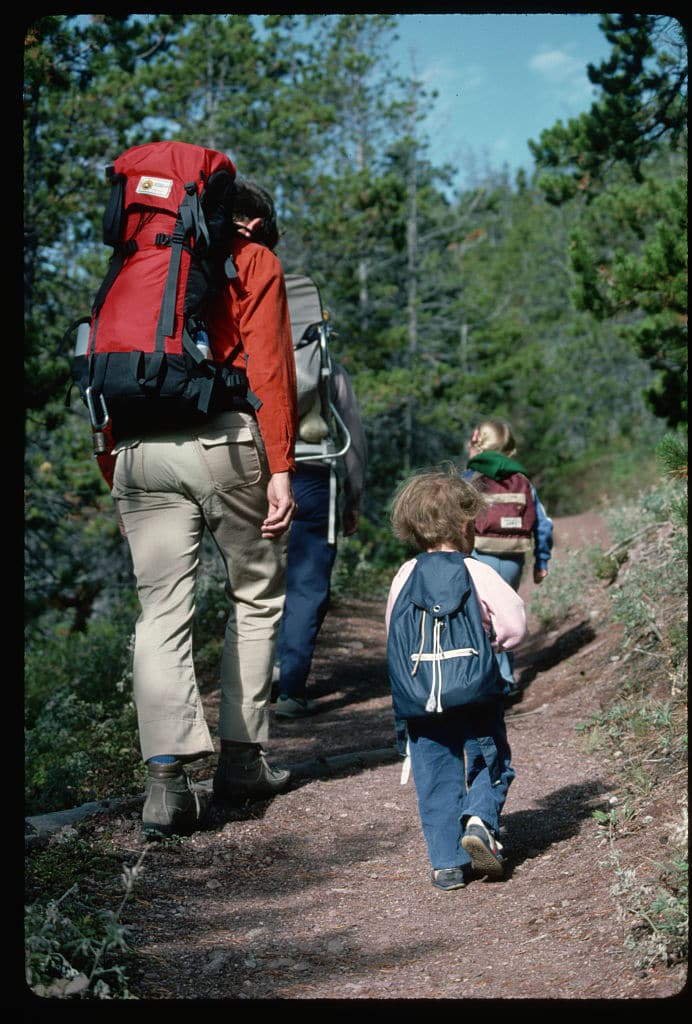

Take a weekly hike. While you might associate hiking only with state and national parks, almost every city has smaller wilderness areas, nature preserves, and municipal parks that include plenty of trails, and are easily accessible by the suburban or urbanite. You very likely don’t have to drive more than a half hour to get a good dose of nature, and you’ll find exploring your hometown’s little nooks and crannies strangely satisfying — even more satisfying in some ways than visiting a well-known wilderness area. To find these urban trails, check websites like trails.com, and lists of “things to do” in your town on travel websites and blogs.

Hiking is fun for the whole family, but little ones have a shorter attention span than grown-ups. So consider incorporating some of these tips to maintain your kids’ interest in your perambulations:

- The setting doesn’t have to be “perfect.” While adults are more interested in scenic vistas, children don’t care as much for grand views, and pay more attention to what’s right in front of them. Good news for you: the trail doesn’t need to lead to an amazing lookout. Kids will be more interested in the “ordinary” flora and fauna they encounter along the way.

- Prepare to take it loose and slow. Young children also get less satisfaction from simply moving from point A to point B than adults. The “point” of the hike for them is less to get to the end, than just to enjoy themselves. So adjust your expectations accordingly, and forget the idea of a hike as continual movement. Be prepared to move pretty slowly and take breaks to sit, play in the dirt, throw sand, balance on a log, toss rocks, pick honeysuckle, etc.

- Hike to a body of water. While young kids don’t care that much about stunning views, they do love bodies of water. Streams, ponds, whatever it is, it makes them 10X more interested in the hike. Our kids stay more motivated to keep going when they know a pond is ahead. Because once there, they like to look in the water at what’s swimming around and skip stones. There’s just some kind of magnetic attraction between kids (and adults!) and water; use it to increase their compliance.

- Pair a hike with a picnic. This is another tactic that significantly ups the interest/compliance factor for our kids. Make some special picnic foods at home, or let the kids pick out some special stuff at the store, and the outing magically, feels, well more special. When the days are longer, we’ll have our picnic dinner first at the trailhead, and then take a hike. When the days are shorter (but not yet freezing cold), we’ll go for a hike at sunset, and then come back to the park to eat our picnic dinner by lantern light.

- Have a nature scavenger hunt. To heighten your children’s powers of observation and keep them more engaged in the hike, consider doing a scavenger hunt in conjunction with it. Give them a checklist of things to look for; these can be general things you know to expect along the way, or centered on a theme like “Signs of Fall.”

- Try to identify flora/fauna/rocks/constellations. Studies show that children today can identify more corporate logos and Pokemon characters than native species where they live. Knowing/learning the names of plants, animals, and even rocks can help children engage more deeply with nature. Of course, it’s probable your own identification skills are pretty faulty; luckily, there are apps that can help you figure out what it is you’re looking at, whether that’s a plant on the ground or a constellation in the sky.

- Try to identify animal tracks. It’s fun not only to identify things that are actually present, but the clues that indicate something was once there. See if your kids can figure out what animal left a particular set of tracks. (There are apps for this too.)

- Activate your kids’ senses and ask them questions. As you hike along, point out things for your children to touch, see, smell, hear, and even taste (as appropriate!). Then ask them questions, especially along a line in which they’ve already shown interest: “What kind of animal do you think left that track?” “What kind of bird do you think that is?” “Why do you think it’s shaped that way?” “How many colors do you see?” They’ll of course ask you questions too, and while it’s easy to just spout off the answer (if you know it!), try turning the question back to them first: “What do you think it is?” As Sampson observes, “Counterintuitively, children are often looking for our engagement more than our answers, hoping that the focus of their attention will become ours too. By turning the question back on them, we crack open a learning opportunity, a chance for them to actively participate in solving a mystery.”

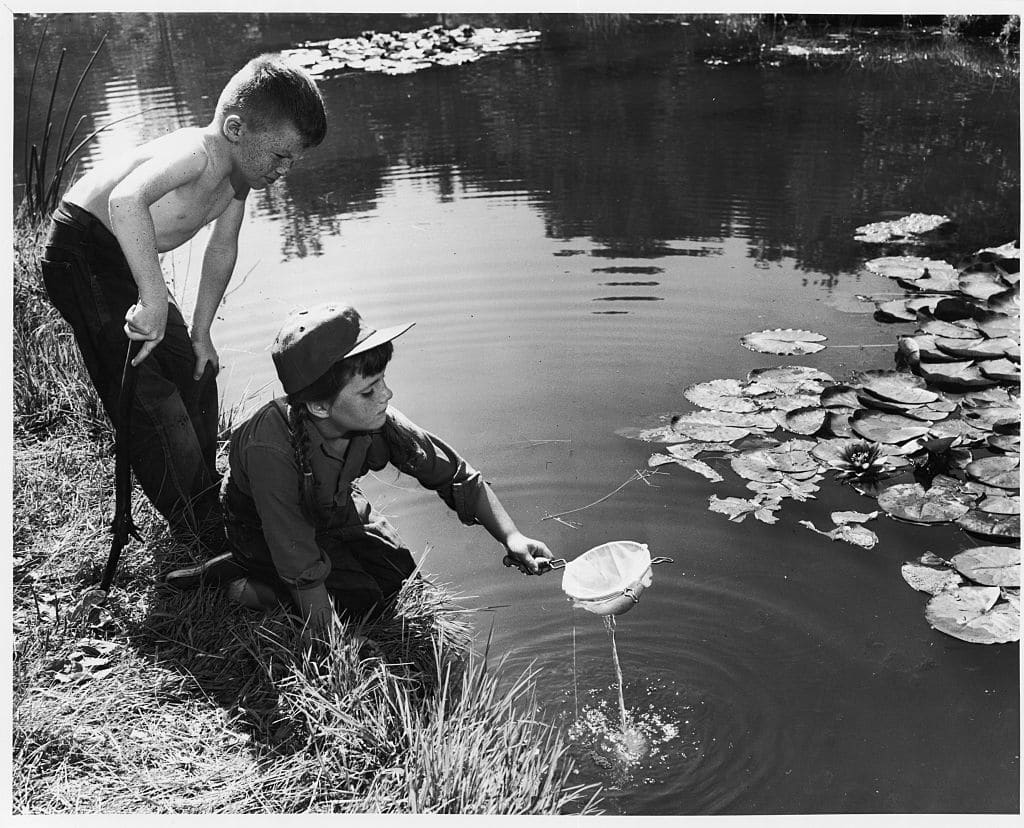

Visit a pond. As mentioned above, hiking to a pond significantly increases children’s enjoyment of the outing. But you can also drive right to a pond, and more easily take along some “equipment” to make it an even more immersive experience. Outfitted in rubber boots, and toting nets, kids can wade into the water, and see what kind of freshwater fauna they can scoop up. There are also often tadpoles to catch (consider taking one home, raising it into a frog, and then releasing it back later), and ducks to feed!

Tend a garden. To kill two birds with one stone and get your kids outside and dirty, start a garden in your yard, and allow your kids to “help” you tend it. You’ll find the most success with this endeavor by planting large seeds that grow quickly, and result in something edible. Children will enjoy watching the plants grow, and be excited to eat the fruit of their labors.

Even if you don’t have room in your yard for a garden (or don’t have a yard), try planting a windowbox garden inside. We recently planted a mere pea shoot in a tin can, and watering it and watching it grow was literally the most interesting thing in our kids’ lives for a couple weeks. It takes a lot less than you think to grab their attention and get them interested in something.

Take a nighttime walk. Your neighborhood, and even your backyard, look very different — and a bit mysterious and magical — once the sun goes down. So have your kids grab a flashlight, and take a walk down the street or through a community park (if safe and legal; some parks have curfews), or hang out in the backyard. Ask your kids if they see, hear, or smell anything that they don’t during the day, quiz them on the phase of the moon, and just enjoy the thrill of twilight.

Monthly

Monthly outings can take you to hikes at state or national parks that are a little further afield or to local nature-centered institutions. You might also undertake activities like hunting and fishing that are slightly more involved than a simple hike. Such activities can of course be engaged in far more than on a monthly basis, but it’s a good minimum to shoot for!

Visit a local nature-centered institution. If you live in or near a decent-sized city, there are almost certainly many nature-centered institutions around town worth a visit. These kinds of places don’t immerse kids in “wild” nature, but they do give them more contact, and more learning/understanding of it. Examples include:

- Zoos

- Aquariums

- Natural history museums (of the non-domestic variety!)

- Planetariums

- Nature centers

- Working farms (kids can sometimes milk a cow, feed the chickens, etc.)

- Pick-your-own fruit/vegetable farms (our kids have really enjoyed outings to pick strawberries, blueberries, blackberries, and apples)

Visit a state or (relatively nearby) national park. A lot of great state/national parks are probably only a couple hours away from you. They often not only have trails to hike but canoes to rent, lakes for swimming, and even mini golf (remember, you don’t have to have a perfectly “wild” excursion to accomplish the goal of getting your kids outside and closer to nature). Pack a picnic lunch and make a day of it. Or stay over for the night, either camping outside or shacking up in a park cabin.

Go fishing. Kids love bodies of water even more when they pull something surprising out of the water! Five is a good age to take children fishing for the first time (though younger siblings can hang out around the lake/pond), and you’ll want to start them out with a simple rod and reel. Try to go somewhere with a good chance of their getting a catch; fishing involves patience, but kids have less of it than grown-ups do, and you want to get them, well, hooked.

Or hunting. While hunting sometimes gets a bad rap these days, it’s a great way to get kids immersed in nature (and turn them into future conservationists). When you hunt, you spend about 95% of the time just sitting quietly in the wilds and observing. While you’re stalking your game, your kids can learn things like how bucks rub their antlers on trees to scrape off their velvet as well as mark their territory, how and why animals move, and what the animal you’re hunting eats. You can take your 6- or 7-year-old along with you on a deer hunt as an observer. In most states, kids can start actually hunting themselves when they’re 10 years old (after taking a hunter’s safety course). When your kid’s ready to hunt, start with small game like squirrel or rabbit.

Yearly

While it’s not possible for most families to take a bigger dive into the wilderness on a regular basis, getting an annual dose of more immersive nature is within reach for just about everyone. You can of course take such trips more frequently as your schedule and locale allows, but making it at least a yearly tradition is a good goal to strive for.

Take a multi-day camping trip. Pick a park, state or national, that’s more secluded and quiet (the presence of mini golf is a bad sign). Live out of your tent, take hikes, bathe in the nature around you.

Take nature-centered vacations. In addition to a yearly camping trip (or in substitute of it, if you have a roughing-it-averse spouse), try to take your annual family vacation to a place that will allow lots of outdoors recreation. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve come to feel that vacations to big destination cities don’t seem very restorative; they’re too artificial, too homogeneous, too busy — too much like my ordinary life back home. I crave something that feels significantly different, that allows me access to things I can’t access in the burbs. Mainly, bigger doses of nature.

So, we generally take our family vacations in places that will allow for lots of outdoor excursions. Of course, I want to relax and have fun too (and so do the kids!), so we go to an outdoorsy place like Utah or Vermont, and rent a house with normal, comfortable amenities that’s close to parks and hiking trails, but not too far from a decent-sized town. Kate and I will take daily hikes on our own in the morning, trading off watching the kids. Then we’ll do a short family hike altogether. After that it’s on to doing normal vacation things — visiting museums, historical sites, attractions — for the rest of the day. We all get out into nature with more frequency than we do back home, and the trip really restores our individual and collective spirits.

If you’re not sure of a good place to take a town/country vacation, and don’t want to plan one out yourself, consider staying at a ski resort. Many stay open in the summer, and offer comfortable accommodations, ample outdoor recreation (hiking, mountain biking, fishing, rock climbing, horseback riding), and fun activities for the kids (land tubing, slides, mini golf, crafts) — all in one place.

Visit (and farm your kids out to) relatives who live closer to nature. Growing up, I always looked forward to visiting my grandfather’s ranch in New Mexico. I loved making hay bale forts in the barn and riding horses. When Kate was a kid, she loved visiting her Uncle Buzz in Vermont, and exploring the trails of the “wild” park up the street from his house. As a teenager, her parents even let her spend a couple weeks up there by herself, an experience she relished.

If you don’t live by much nature yourself, but have relatives who do, consider visiting them from time to time. Even consider farming your kid out to a relative for a week or two. Your kids will love it, and so will the relatives (well, depending on their relationship, and the kid’s behavior!).

Send your kid to summer camp. A great way to get your child more immersed in nature, and boost their sense of confidence and independence, is to send them to a sleep-away summer camp. They’ll be doing outdoor activities each and every day. Just be sure it’s a camp that bans technology. There’s no point of paying a couple thousand dollars for your kid to spend her time staring at the same smartphone screen she does back home!

Additional Tips to Keep in Mind for Greater Success in Increasing Your Child’s Contact With Nature

Hopefully in journeying through the different levels of the Nature Connection Pyramid, you’ve come to see that you don’t have to live in the wilderness or regularly visit grand national parks to increase your kids’ contact with the outdoors The bulk of their “nature diet” should consist of small, doable outings that are easy to execute on a daily, weekly, and monthly basis. By simply creating doable goals for each of those levels, as well taking at least one wilder excursion each year, your child will absorb plenty of Vitamin N.

Here are a few more tips for making these efforts a success:

Adjust your goals/plans to a child’s age/abilities. There’s no one-size-fits-all nature-connection plan for families. E.g., little kids don’t have the attention span for long hikes; teenagers do, but expect more out of them. Adjust the type and intensity of your outings according to the needs of your particular children, and know that even infants and toddlers can explore their backyards (and go on camping trips) as long as they have willing and patient parents!

Lead by example. “If a child is to keep alive his inborn sense of wonder,” wrote the famous naturalist Rachel Carson, he “needs the companionship of at least one adult who can share it, rediscovering with him the joy, excitement, and mystery of the world we live in.”

The biggest reason kids don’t spend more time in nature is that their parents don’t. If your children see you’re not interested in and don’t value the outdoors, neither will they. Conversely, if you lead by example, showing them a genuine love of nature yourself, they’ll typically adopt the same attitude.

Your job then is to be an outdoor mentor for your kid, or as Sampson puts it, a “matchmaker” who facilitates your child’s lifelong longing and love for nature.

To effectively act as this kind of mentor, you ought to have at least one nature-centered hobby yourself: hiking, trail running, snowshoeing, rock climbing, canoeing, fishing, gardening, etc. You’re less inclined to get your family outside unless you have a compelling reason to do so, and such a hobby provides one. Your kids will be interested in what you’re up to, and as they get older, they’ll be able to tag along as you participate in your favorite outdoor activities. A nature-centered hobby offers your child a chance to spend quality time with you, and often learn new skills to boot.

Outside of participating in your chosen form of outdoor recreation, you can demonstrate your interest in and love for nature to your kids in little, everyday ways. When you see a beautiful sunset or interesting cloud, point it out. Say, “Isn’t that a pretty sky?” “Isn’t that an interesting tree?” Instead of walking around in a stupor, blind to nature’s marvels, show your kids you pay attention to, and still find some awe in, your natural surroundings.

Ultimately, spending time in nature should just seem like a normal, natural part of your and your family’s life. In making it such, it’s likely to become that way for your child as well.

Be intentional — schedule time in nature. Nothing good happens without being intentional about it. If you just kinda, sorta hope to spend more time outdoors, it won’t happen. You’ve got to schedule it. At our weekly family meeting, we always discuss what microadventure we want to do that week, and then mark it down on the calendar. It increases a hundredfold the likelihood of such outings happening.

Remember you’re helping to make memories for your children, and for your family. Some of mine and Kate’s best, as well as most profound memories, are from times we spent in nature as children and young adults. That’s not unusual. Research shows that most transcendent childhood experiences happen in nature. The times you let your kids go off into the woods by themselves can literally be life-changing for them, shaping their vision of who they are, inspiring their take on the meaning of life, and creating some of their most indelible memories.

The time you spend in nature with your children, will create some of your best memories as a family as well. Already some of my fondest memories of me, Kate, and our kids are of the outings we’ve taken together. Nothing major — we haven’t done any big camping trips or visited any national parks yet. Just the little excursions to local preserves that won’t ever be featured in glossy magazine spreads. Just our ordinary weekly picnics and hikes. Gus and Scout toddling along between the trees. The sun sinking behind the horizon. A chill rising in the evening air. It might not be perfect, but it sure feels a lot like heaven.

______________________

Sources:

Last Child in the Woods by Richard Louv

How to Raise a Wild Child by Scott D. Sampson