Last week we discussed why every man should delve into his genealogy, arguing that doing this kind of family history research is not only fascinating, but constitutes a moral obligation. Filling out your family tree both enriches your personal sense of identity and honors the ancestors who bequeathed the gift of life to you.

Today, we present the how of genealogy – a comprehensive guide to the basics of getting started with researching your family history and keeping the memory of your forebearers alive.

Pre-Gaming Your Genealogical Research

Family research is a journey. And like any journey, you want to do a bit of planning before you set out. Here are a few things to do before you throw yourself headlong down the genealogy rabbit hole.

See What’s Already Been Done

Before you start looking up names in census records, see what genealogical research has already been done in your family. Chances are you have that one aunt or cousin who’s really into family history and already has a great deal of it gathered and recorded. Connect with them and ask if they can share what they’ve collected thus far.

If you sign up for a family history service like Ancestry or FamilySearch, you may find that a lot of your family tree has already been filled out by your relatives, both close and distant.

For example, when I recently started doing my own genealogy, I knew a good amount of my family history had been done on my mom’s side, but thought it was pretty much non-existent for my dad’s side. But when I signed into FamilySearch a few months ago, I discovered that my sister had been quietly entering in history for my dad’s half of our family tree, and making connections to research that had been done by others on the site.

So, as you begin doing your genealogy, first browse through the research that’s already been done and enjoy the feeling of learning more about your family’s history. Then start looking for places where you can add to the story.

Perhaps there’s a family line that suddenly stops because there’s a missing piece of vital information. Or maybe your family history buff relative has information like dates of births and marriage for your great-great-great-grandparents, but not much biographical information about them, such as what they did for a living. That’s an area you could look into.

In short, use the genealogical research that’s already been done to guide the direction of your own research.

Collect Perishable Information and Digitize It

Genealogy is more than just a family tree. It’s the story of you and your family. Remember, we’re trying to prevent the “second death” of our ancestors by recording and remembering their stories. So when you first start out, spend your time gathering information that will help you put together the narrative of your family, particularly information that’s perishable.

What are perishable sources of genealogical information?

Humans, for one. Living people die, but living people often have the most useful and meaningful family history info stashed away in the treasury of their still extant craniums. Extract that family information from them before they depart mortality. Interview older relatives and record their personal stories and what they remember about your ancestors. Your grandpa will likely have stories about his grandpa. Ask him to tell those tales while you record him with a digital recorder. Make interviewing older relatives a top priority in your genealogical research; it’s something you always swear you’ll get to…until it’s too late.

Other sources of perishable family history information include photographs, diaries, letters, and other documents. That stuff will deteriorate with time and can be lost. Once it’s gone, it’s gone for good. Collect and scan such records for digital storage. Regarding photos, make sure you can identify everyone in them. That may mean asking an older relative for help.

You can do the digitizing of perishable information yourself, but that’s a laborious process. If you’re short on time, consider outsourcing the job to a service that specializes in digitizing family history photos and documents. Sites like Memories Renewed and DigMyPics can do that.

Establish Genealogy Goals

When you first start out, genealogy can seem intimidating. There are so many directions to follow with your research. It can be so daunting that it’s tempting to give up before you even begin.

To overcome this genealogical inertia, establish some very specific and very modest goals for yourself.

Your goals depend on how much information you have and what genealogical research has been done already. For someone who’s starting from scratch, a good goal is to fill out the family group sheets (more on these in a bit) for your family, going back to all eight of your great-grandparents. This goal will provide plenty of information that will lay the groundwork for the rest of your genealogical research.

As you complete this goal (and others), focus on one family unit at a time. It’s tempting to jump from one line to the next, but in order to keep your work organized and progressing, don’t move on to another family line until you complete the research and recording for the one you started.

If you find in your pre-game research that a lot of your family tree has been done for one side of the family but not the other, focus on the side that doesn’t have much work done, remembering to take it one family unit at a time.

If your family already has a well filled out family tree on both sides, start going deeper in your genealogical research. If the low-hanging fruit has already been picked, go further back than anyone else has. Or, concentrate on fleshing out the biographical information of the ancestors already captured to create a more thorough family story: Interview distant relatives and record their memories; visit archives to find primary source documents relating to an ancestor; read history books about the time and place a particular ancestor lived so you can get a better understanding of their way of life.

The deeper you go with your family history research, the richer the family story you’ll develop.

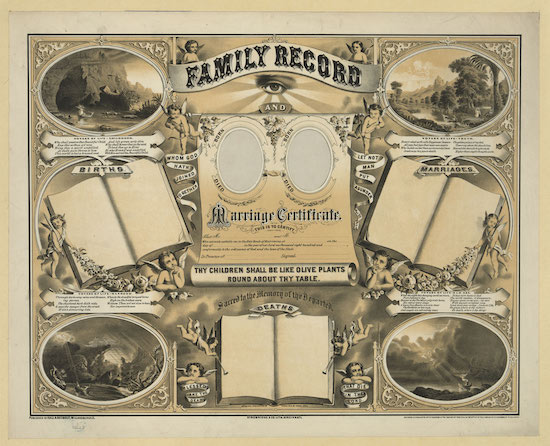

Print Off Blank Family Group Sheets

While you can keep track of your genealogical research online or with a program, with family history research, I’ve found that there’s one form that’s worth filling out by hand: family group sheets/records.

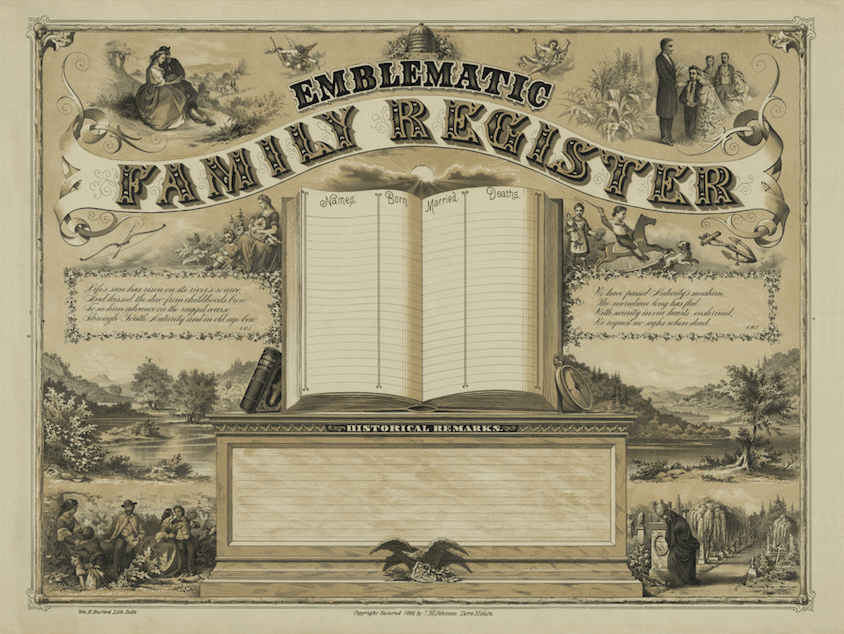

Family records are the roadmaps for your family history research. A family group record shows the names of the mother, father, and children in one family unit. It also shows dates of birth, dates of marriage, death dates, names of the parents’ parents, additional spouses of the parents, and the names of children’s spouses.

Some family group records have places where you can fill in even more details like occupations, religion, military service, and property acquisition. Great for fleshing out the story of your family!

The information you record in your family group record can provide clues on where to take your research next or places in your family line that need to be verified or better documented.

Once you’ve filled out a family group sheet by hand, filling out your digital family tree is a breeze. When I first started filling in blank spots on my family tree, I tried just doing it online and jumping from tab to tab with research that I had done. I quickly found myself losing track of what I was searching for. Having a paper copy of the family group record next to my computer eliminated the confusion. Also, because a family group record focuses on one family unit at a time, it forces you to stay focused on just that unit. There’s no temptation to jump around from one line to the next.

Starting Your Genealogical Research

You’ve done your prep; now it’s time to dig into your family history. Here’s how.

Create an Account on FamilySearch and/or Ancestry.com

Thanks to the wonders of the web, genealogical research has never been easier. Just thirty years ago, genealogical research required visits to family history libraries and hours upon hours of scrolling through microfiches to find ancestors. Now you can search billions of records online in a matter of minutes, thanks to online family history services.

In the world of online genealogy stand two behemoths: Ancestry and FamilySearch. Both allow you to search billions of genealogical records and to create and organize family trees.

However, there are differences between the two.

First, FamilySearch is free. It’s owned and run by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints and they’ve made it available to Mormons and non-Mormons alike at no cost.

Ancestry.com will cost you about $20 a month for their entry-level package.

Both boast extensive libraries of genealogical records. Ancestry has indexed and scanned all the U.S. Census records from 1790 to 1930. FamilySearch doesn’t have all those records in its database. However, FamilySearch offers international records and immigration records for free that Ancestry charges a pretty penny for ($150).

Moreover, FamilySearch has begun indexing Freedmen’s Bureau Records — records of freed African-American slaves that were created after the Emancipation. If you’re primarily searching for genealogy stateside, you’ll likely find more leads on Ancestry. If your research is more international in scope or you have African-American ancestors, FamilySearch might be more helpful.

Regarding searching for genealogical records, the online chatter amongst family historians suggests that FamilySearch has a more useful search algorithm, allowing users to find the information they need more quickly.

Finally, the ways FamilySearch and Ancestry do their family trees are different, and they both have their pros and cons. Ancestry has a nice feature that will provide hints for further lines to investigate for possible connections. If the system finds a possible link, a small leaf will appear on the corner of an ancestor. Just click on it, and you’ll be shown their possible relatives. I was able to fill out an accurate family tree in a matter of minutes based on these hints from Ancestry.

FamilySearch opens up family lines to be edited by anyone (including FamilySearch librarians who verify information). You can quickly piece together a family tree based on the work of others who have been using the site.

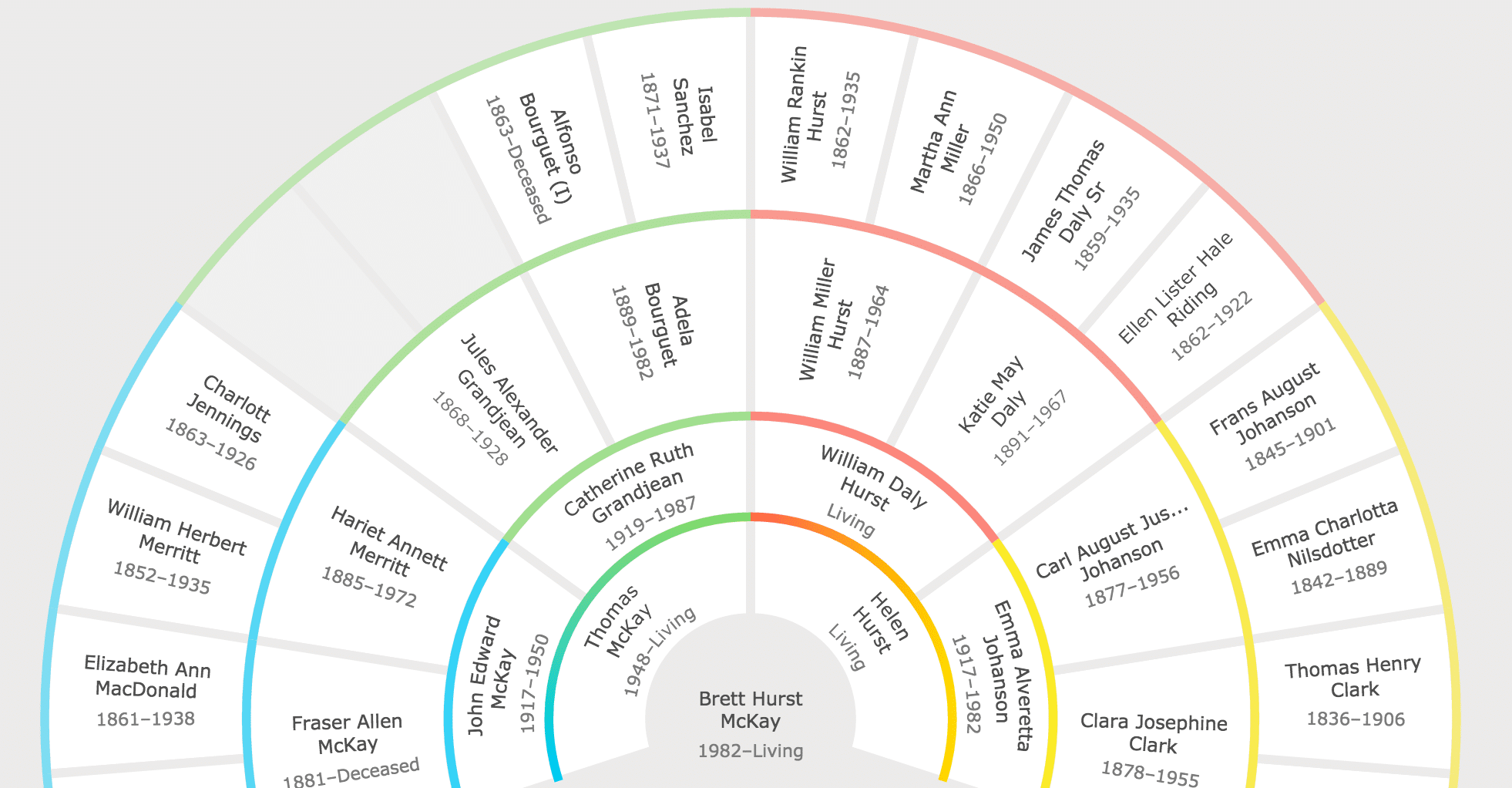

Overall, I did find the family tree on Ancestry much easier to use than the one on FamilySearch. Though I did like the cool format that the latter can put your tree in (see image below).

Another nice feature about both Ancestry and FamilySearch is that they have forums where people can ask questions and swap research. I’ve come across useful discussions about ancestors that I’ve been investigating in both forums.

What’s the bottom line? If you’re just starting out and don’t want to spend money, go with FamilySearch. You’ll likely find connections in your family tree pretty quickly with their crowd-sourced info. If you’re coming up against some dead-ends in your family history research, sign-up for an account with Ancestry.com to get access to records you might not be able to find on FamilySearch.

Other Places to Look for Family History Information

While FamilySearch and Ancestry are the heavy hitters in the genealogy game, you shouldn’t limit your research to them. Other online services exist that allow you to search and store your family history. They include:

If you’re hitting dead ends with your family history research, it doesn’t hurt to check these other services out. While their databases aren’t as robust as Ancestry or FamilySearch, they often have records that you can’t get anywhere else. I came to a dead-end with a great-great-great-grandfather (didn’t have the name of his spouse) on Ancestry and FamilySearch, but found the info I needed on MyHeritage.com.

Newspapers.com is another great storehouse of possible family information. It’s a digital archive of newspapers dating back to the 1700s. There are thousands of papers, and millions of pages digitized. While it costs money to use (there’s no free account), there is a 7-day trial in which you could binge-research and find out if it’s worth paying for.

Don’t limit your searches to the main interfaces of websites either, but also check out their forums (as well as sites that only exist as forums). Besides the forums on Ancestry and FamilySearch, RootsWeb and GenForum have active discussions going. Search them for ancestors you’re looking for.

If you’re looking for software to keep track of your family history research, check out the following. While they’re mostly focused on collecting and organizing your genealogy, many of these apps connect to databases so you can also do some basic searching:

Another place to check online are websites that individuals have created where they share the personal genealogy they’re doing. You’ll find lots of sites dedicated to particular surnames or family lines.

If you come up short on info online, you may need to call or visit archives, libraries, parishes, churches, and cemeteries located where an ancestor lived or died to get the info you need. In some cases, you can also find research assistants in those localities to help out for a small fee. Our Managing Editor, Jeremy, had some family letters located in a research library in California that could only be accessed in person. Rather than making a trip to the coast, he was able to contact the library, and they gave him a list of contacts who were willing to do the research and even make photocopies on a freelance basis.

Being a Family History Sleuth & The Need to Make Educated Guesses

You’re bound to come to dead ends with your genealogy. Maybe you know the name of a great-great-great-grandfather, but that’s all you’ve got. You don’t have the name of his spouse, his birth date, birthplace, death date, or death place. You’re not going to be able to go back any further with your research unless you get those pieces of information.

What to do?

Well, you’ve got to put on your detective hat and start testing various leads. If, say, you do know the birth date and birthplace of your great-great-great-grandfather’s son, a good guess would be that he died in that location or near there, so search for the name of your great-great-great-grandfather and narrow the search so that his place of death corresponds with the town where your great-great-grandfather was born.

This is an exact scenario that I had to use to find some missing information about a great-great-great-grandfather on my dad’s side, and I found the information I needed by doing exactly what I described above.

Another thing to try if you’re coming up against dead ends is changing the spelling of the last name. Often, European immigrants to the U.S. would do this in order to make their surname sound more “American.” For example, many Scots from the clan MacKay changed the spelling of their last name to “McKay” when they immigrated to Canada and the U.S.

The trick when you come up against dead ends is to use the information that you do have and see where it takes you.

21st Century Family History: Genetic Genealogy

If you’d like to find more family connections, consider getting your DNA tested to find distant relatives. Companies like 23andMe and Ancestry.com offer genetic testing for $100. Just spit into a vial and send it in the pre-paid box. In a week, they’ll present potential living genetic relatives on your online “dashboard.” These folks might be excellent sources of genealogical information that you’re missing. Reach out to them and swap information.

One thing to keep in mind with DNA testing is you may discover some unpleasant family secrets, like, say, a half brother or sister from your dad’s time sowing his wild oats as a young man (or from an affair). Be prepared for that sort of thing. It’s happened.

What If I’m Adopted?

If you’re adopted, you’ve got a few ways you can go about researching your family history.

Your adoptive family is your family, and while you haven’t inherited their genes, you’ve inherited their family culture and heritage. Therefore, your adoptive ancestors are your ancestors, too. You shouldn’t have any qualms about doing the genealogy for your adoptive family. Just be sure to indicate that you were adopted in your family chart.

If you know who your birth parents are, you can also do the family history for your birth family. This would require keeping track of two family trees — one for your adoptive family and one for your biological family.

Establishing Credibility of Information

When you’re doing genealogical research, it’s tempting to just take pieces of information at face value. I made the mistake of filling out my digital family tree with a line of ancestors I thought were connected to my great-great-great-grandfather. I didn’t do too much due diligence. A few days later, I uncovered information that completely blew up that work, and I had to start over again. That’s why verifying and establishing credibility is so important with genealogy.

While you likely won’t be able to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that a connection is indeed a connection (this is especially true as you go further down your family line), you should be pretty confident that your information is reliable.

When you’re evaluating a piece of genealogical information for its reliability, use the five elements of the Genealogical Proof Standard:

- A reasonably exhaustive search has been conducted.

- Each statement of fact has a complete and accurate source citation.

- The evidence is reliable and has been skillfully correlated and interpreted.

- Any contradictory evidence has been resolved.

- The conclusion has been soundly reasoned.

If you can say that you’ve met these elements, you can safely assume that the info is reliable. Of course, you should be open to changing your opinion on established family connections as new information emerges.

What to Do With Your Family History

So you’ve been doing family history research and are making good headway. What do you do with it?

Well, it depends on how deep you want to go.

If you’re only interested in seeing your family connections, just stick to filling out your family tree. For most folks, that’s about all the genealogy they’ll want to do.

If you’d like to put together a more detailed story of your family, consider writing a thorough family history complete with background information about your ancestors’ occupations and even the period they lived in.

Creating a scrapbook filled with family trees, photos, and copies of relevant documents is another option. It’d be nice to have a big binder sitting around your house that you can open to meditate upon your ancestors and pass down to your progeny.

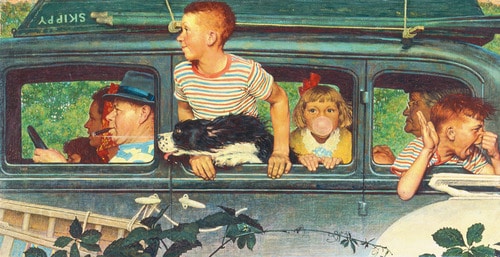

You can use your research to plan a pilgrimage to your ancestors’ homeland or plan a big family reunion (like Esquire editor A.J. Jacobs did a couple years ago).

Most importantly, share your genealogy with others. There’s probably some guy out there looking for a piece of information that you have. Put it up online at one of the many online genealogy services, or create a website where other family members can enjoy it.

Well, there you go: how to get started with genealogy. I hope you found this intro useful, and have been inspired to redeem your ancestors from the second death, and find a richer personal identity for yourself.

Now if you’ll excuse me, I need to get back to tracking down the parents of one John MacKay born around 1770 in Scotland and married to Mary Campbell. If you have any info on him, send me a Tweet or a letter. Thanks, cuz!