Editor’s note: This is a guest article from Kyle Eschenroeder.

“The best thing is to want what is right (the honesta) and not to stray from the path.” –Seneca

“[W]e go to far less trouble about making ourselves happy than about appearing to be so.” –La Rochefoucauld

“My life … is for itself and not for a spectacle.” –Ralph Waldo Emerson

“To think that I’ve wasted years of my life, that I’ve longed to die, that I’ve experienced my greatest love, for a woman who didn’t appeal to me, who wasn’t even my type!” –Marcel Proust

My biggest fear is to live a life I regret.

It’s easy to fall into the trap Proust is talking about and spend life blindly chasing something you never actually wanted.

Blindly following your desires makes you a slave to your impulses — slave to the assumptions of those around you, the advertisements you’re exposed to, and the confused chemical signals of your body.

Our default is to spend our life as rats blindly chasing the next dopamine hit.

This isn’t a setting easily adjusted, but it’s worth shifting our aims and becoming fully human.

If we don’t pause and ask ourselves what we want to want, we will spend our lives focused on unhealthy aims defined for us by others and the worst parts of ourselves. We will pass these bad assumptions about life onto our children and loved ones. We will reinforce these boring, desperate defaults in everyone we encounter.

To achieve freedom we must be able to think for ourselves. If we don’t cut to the core and reprogram our wants (our desires) then our best-case scenario is to be the most successful, rich, or famous slave. If we never peer into our programming then we may end up the cleverest rat, but that’s hardly worth celebrating.

Asking yourself what you want to want can help you avoid wanting the wrong things.

It can also help with existential crises, disillusionment, and other crises of desire. The current culture has betrayed us in the way it programs our desires. It’s exhausted many of us to the point where we’re wary of wanting anything at all.

Asking this question may give you the ability to desire again — to trust in yourself and your aims:

What do you want to want?

To answer this question seriously we have to understand what it is and why it matters, so we’ll start there.

We’ll then look at two ways in which we can start ridding ourselves of society’s default desires, and discover and shift to living out our own.

Let’s get into it.

You Are What You Want

There’s never been a time in human history where it was easy for someone to trade in their status quo wants for deliberately chosen desires, but we live in a period where this project is particularly difficult.

There’s no single dominant, cohesive culture and there are endless options — a million different lifestyles and beliefs to try on and a never-ending buffet of things to want. There are a million advertisers and content creators competing for your attention, playing on your insecurities. It’s a time of acute cross-pressures, and folks aren’t sure which way to go.

In such a period, people don’t have the willpower to sort through the barrage of options, and they default to the kinds of things that please their biological cravings (food, sex), or the kinds of pursuits that have been desired by humanity for thousands of years (wealth, fame, power).

It’s a dizzying time, but not a wholly unique one.

The ancient Roman philosophy of Stoicism was born in a time of anomie, or “normlessness,” similar to ours. Their social structures were breaking down; the normal societal games used to divvy up honor and respect were broken.

Carlin Barton puts it this way in Roman Honor: “With the loss of the rules and conditions of the good contest, the entire language of honor ‘imploded’ and had to be ‘reconstructed.’” Imagine the anxiety this would cause a society that was built completely around living for honor.

The early Stoics had to go back to foundational principles to discover what truly mattered in life. They had to ask themselves the question we’ll look at here:

What do I want to want?

Many of the stable arenas in which a Roman could formerly earn the respect of his peers had collapsed. Into this vacuum stepped the Stoic philosophers, who offered guidance on how to navigate their newly fragmented world.

For this reason, these ancient philosophers are particularly helpful in illuminating what ails modernity and teaching us how to reconstruct a system in which we can thrive. For example, Seneca makes this observation about folks who didn’t take charge of what they wanted in his time:

“If you ask one of them as he comes out of a house, ‘Where are you going? What do you have in mind?’ he will reply, ‘I really don’t know; but I’ll see some people, I’ll do something.’ They wander around aimlessly looking for employment, and they do not what they intended but what they happen to run across. Their roaming is idle and pointless, like ants crawling over bushes, which purposelessly make their way right up to the topmost branch and then all the way down again. Many people live a life like these creatures, and you could not unjustly call it busy idleness.”

Sounds familiar, right? Such drifting may be as old as civilization itself, but we don’t have to take part.

In times of uncertainty and flexibility, like Seneca’s and ours — when everything seems to be in chaos and nobody knows what’s going to happen next — knowing what you want to want, and being able to reprogram your default desires, is both vitally important and uniquely possible.

Why What You Want Matters

“Every chance of stimulation and distraction is welcome to [the mind] — even more welcome to all those inferior characters who actually enjoy being worn out by busy activity. There are certain bodily sores which welcome the hands that will hurt them, and long to be touched, and a foul itch loves to be scratched: in the same way I would say that those minds on which desires have broken out like horrid sores take delight in toil and aggravation.” –Seneca, Tranquility of Mind

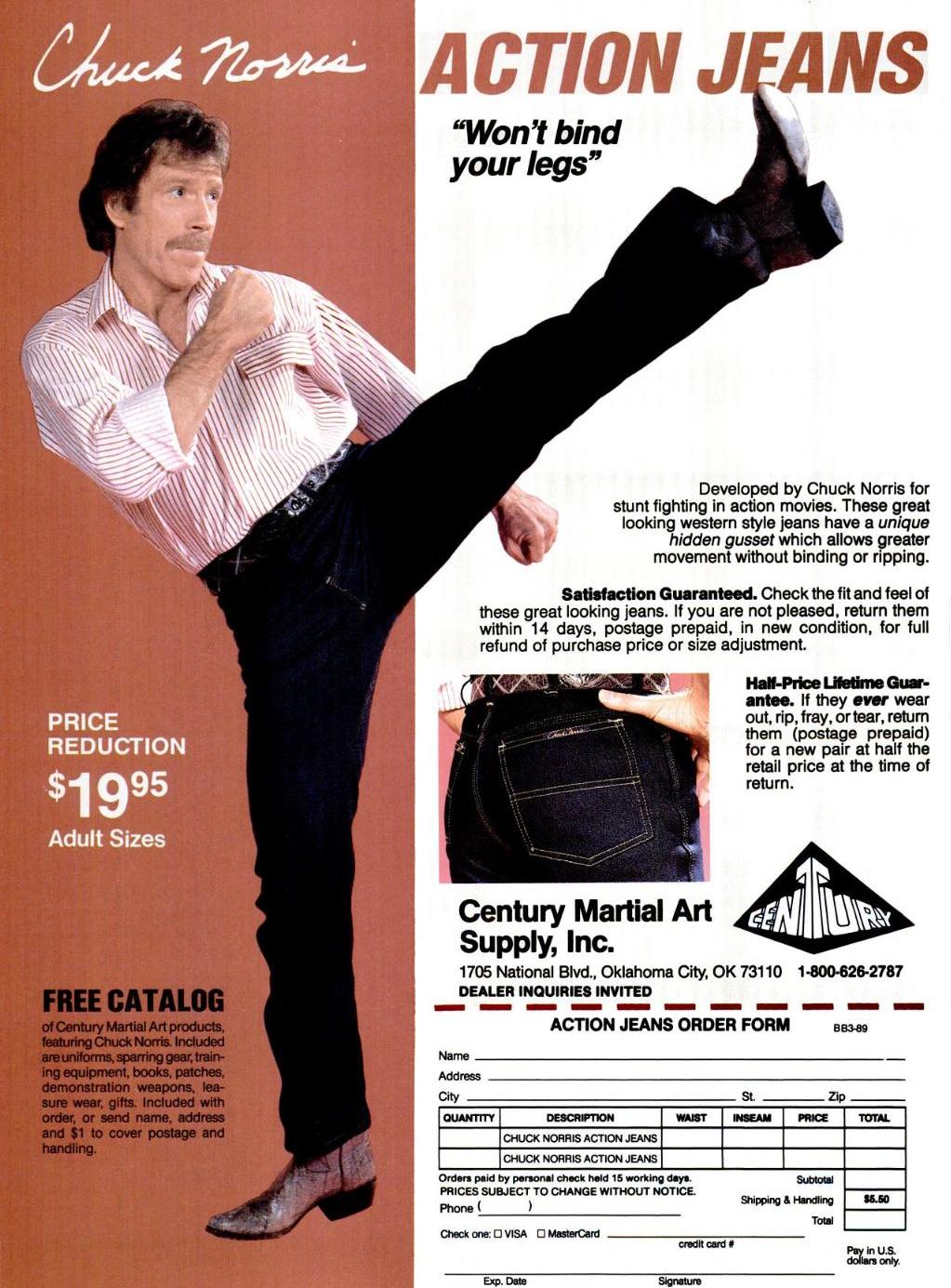

When Jack London and his wife were preparing to make a sea voyage in a small ship, their friends called them crazy. They didn’t understand why London would willingly do something so difficult, so dangerous. Yet for London, it was the “path of least resistance” — it was as easy a decision for him as staying on land was for his friends. He reports on why he made the trip:

“The ultimate word is I Like. It lies beneath philosophy, and is twined about the heart of life. When philosophy has maundered ponderously for a month, telling the individual what he must do, the individual says, in an instant, “I Like,” and does something else…

That is why I am building the [ship]. I am so made. I like, that is all.”

His default desire was adventure, and so adventure was the obvious choice.

Our desires define our own paths of least resistance.

Psychologists have discovered that we all have limited willpower. This means that if you’re fighting uphill to do the right thing, you’ll eventually lose.

Your desires are like channels cut through the landscape of your life; water (your behavior) will automatically flow whichever way these arteries have been carved and directed.

If you live life passively, these channels are made up of mindless, ingrained defaults formed by your biology and the pressures of society.

The good news, however, is that these channels are not set in stone and can be deliberately altered; you can create new conduits of energy that flow in directions of your own choosing.

Those who consider seriously what they want to want will be miles ahead of those who remain reactionary to media, ads, and their blindly-chosen peer groups.

Putting in the work now to create your own defaults will pay massive dividends for the rest of your life.

The Possibility of Reprograming Your Default Wants

It’s not easy to move away from the default settings instilled by biology and culture in order to reprogram your wants. But it’s not impossible either.

The benefits of setting your own default desires have been recognized for millennia. Confucius considered this kind of reprogramming essential to realizing wu-wei — action that comes naturally. Edward Slingerland explains the process of its attainment in Trying Not To Try:

“In the early stages of training, an aspiring Confucian gentleman needs to memorize entire shelves of archaic texts, learn the precise angle at which to bow, and learn the lengths of the steps with which he is to enter a room. His sitting mat must always be perfectly straight. All of this rigor and restraint, however, is ultimately aimed at producing a cultivated, but nonetheless genuine, form of spontaneity. Indeed, the process of training is not considered complete until the individual has passed completely beyond the need for thought or effort.”

In other words, through deliberate training that at first feels tedious, we eventually arrive at a point where we want what we want to want.

Reprogramming your default wants (habitual desires) and achieving wu-wei can take a lifetime. Confucius measured his progress not in days, weeks, or even years, but in decades:

“At fifteen I set my mind upon learning, at thirty I took my place in society; at forty I became free of doubts; at fifty I understood Heaven’s Mandate; at sixty my ear was attuned; and at seventy I could follow my heart’s desires without transgressing the bounds of propriety.”

We probably will never reach the ultimate point that Confucius describes (only partially because we may find it impossible to determine the perfect thing to want to want!) but are guaranteed to make progress if we work at it.

How to Discover What You Want and Actually Want It

“We do not know what we want and yet we are responsible for what we are — that is the fact.” –Jean-Paul Sartre

“If I consider my life honestly, I see that it is governed by a certain very small number of patterns of events which I take part in over and over again.” –Christopher Alexander, architect

Once you understand that you are what you want, and that you can reprogram your wants, then the task is to discover what you want to want in life, and how to want what you want. You can do that by 1) experimentation and seeking direct experience, and 2) surrounding yourself with those who want the same things.

Direct Experience: Seeing Things as They Are

“We suffer primarily not from our vices or our weaknesses, but from our illusions. We are haunted, not by reality, but by those images we have put in place of reality. And all the while, reality — the kind of reality at Lincoln’s address, that slow unfolding of everyday life — goes on behind the scenes, largely unnoticed. As we scream at the flashing digits, wave at the man in the cape, and devour every entertaining snippet that news hounds throw up, life passes on by.” –New Philosopher issue #10, Famous for $15

“It is not industry that makes men restless, but false impressions of things drive them mad.” –Seneca, Tranquility of Mind

When we want the wrong thing it’s usually because of a distortion or abstraction. When we can’t see clearly we can’t want clearly.

One of the best ways to consistently know what you want to want is to pay attention to your direct experience. That means being present with what is actually going on.

There’s no better way to do this than experiment.

Poke and Prod

“All life is an experiment. The more experiments you make the better.” –Ralph Waldo Emerson

Studies on happiness have shown that our immensely useful ability to imagine the future is just about useless in helping us determine what will make us happy.

Because our imagination is so great at so many things, we rely on it even in situations where it’s useless. The best trick I’ve found to counter this is to develop a bias toward action.

A bias for action is the best way to ensure that we stay connected to reality; which is, in turn, our best defense against wants we don’t want to want.

Instead of spending our lives imagining what things might be like, we’re often better off trying them out and seeing.

Whether it’s changing careers, adopting a new mindset, or anything else, it’s possible for us to try the decision on and test it for ourselves.

We can set up experiments to see how we actually like each of them.

If we do this consistently we will move reliably toward the wants we want to want.

For instance, we might be convinced that we need to become an actor after seeing a movie. It’s not until we start the process of taking acting lessons and going to auditions that we can actually know whether we like acting. The repetition of scenes, constant rejection, and emotional labor can only be understood with direct experience.

Direct experience will help us refocus on life’s proper path. The glittering path may look better at first, but as we begin to walk it we begin to see the hidden costs: the shallow friendships, the enemies made, the underappreciated role of luck, and all of the other little details hidden from view.

The more vigilant we are about this the more our desires will flow from our experience instead of outside influences. The more we pay attention to our experience the more soundly we can determine what we want to want.

This is because focusing on our direct experience strips our lives of drama, which lives in abstractions. The need to appear a hero or a master of the universe dissipates when you focus on the work at hand.

Antoine de Saint-Exupery memorializes a friend, Guillaumet, who became famous for courage in many life-threatening adventures:

“If we were to talk to him about his courage, Guillaumet would shrug his shoulders. But it would be just as false to extol his modesty. His place is far beyond that mediocre virtue.

If he shrugs his shoulders, it is because he is no fool. He knows that once men are caught up in an event they cease to be afraid. Only the unknown frightens men. But once a man has faced the unknown, that terror becomes known.”

A commitment to experiments and gaining direct experience is a commitment to facing the unknown. It’s a commitment to defanging the terrors of our imagination. Our salvation is likely not in replaying the scenario one more time, but in taking a step forward.

“What saves a man is to take a step. Then another step. It is always the same step, but you have to take it.” –Antoine de Saint-Exupery, Wind, Sand and Stars

Internal Scorecards

“The big question about how people behave is whether they’ve got an Inner Scorecard or an Outer Scorecard. It helps if you can be satisfied with an Inner Scorecard.

I always pose it this way, I say: ‘Lookit. Would you rather be the world’s greatest lover, but have everyone think you’re the world’s worst lover? Or would you rather be the world’s worst lover but have everyone think you’re the world’s greatest lover?’ . . . Now my dad: He was a hundred percent Inner Scorecard guy. He was really a maverick. But he wasn’t a maverick for the sake of being a maverick. He just didn’t care what other people thought.” –Warren Buffett

If we take our eyes off what we want to want for an instant, advertisers and others will take command of our desires. This is why it’s imperative that we stay focused on what we’re trying to achieve with these experiments.

We need a way to measure ourselves so that others can’t dictate our worth.

Imagine a marathon runner and a sprinter side by side. The guy running the marathon will be absolutely humiliated if he thinks they’re in the same race. The sprinter’s ego will likely be blown up. Both will probably change their current pace and mess up their times.

This is what can happen to us if we start using the wrong scorecards. We see someone who has achieved so much more than us. We forget that they’ve been working at it for 10 years, or we’re blind to the sacrifices they’ve made in their personal lives.

Inner scorecards allow us to respect our direct experience by making our aims front and center to us, not detached and floating around culture in ads and TV shows.

Cycling between experiments and internal scorecards helps quiet those outside voices and develops our respect for our experience. We learn to trust in our reality over the cries of conmen and the fearful mob. We can gain the ability to stay the course when proper, and to change routes when needed.

This is all about returning our perspective of experience to something closer to home. Ultimately, we want to judge ourselves by the actions we take over the outcomes they lead to.

Let’s take a look at possible experiments you might run in your own life:

Some Tactics

- Prioritize action over abstraction. Commit to acting in line with what you want to want before wanting and soon enough you’ll find yourself wanting that thing.

- Create habits by stringing enough of those actions together. It’s only after your 20th cold shower that you might begin to enjoy them.

- Meditation will make your actions less reactive by creating distance between “you” and your thoughts/urges/emotions.

- Put yourself in flow situations where you’re immersed in the activity you’re practicing. This is, by definition, the epitome of paying attention to your experience.

- Learn to love depriving yourself of certain habitual desires (like warm showers, sugar, coffee, porn.) This will show you how malleable your wants are. After a while you will begin to feel a certain pleasure in exercising your self-control. Also, your willpower will increase. This can change what you think of desire itself. When you begin to derive pleasure from depriving yourself of those very things you desire you’ll realize how much control you have over these drives.

- Imagine God or someone you respect (grandparent, parent, coach, historical figure, etc.) observing you, this will focus your attention on what you’re doing in a new and powerful way.

- Stream of conscious journaling will help you externalize thoughts so that you might see more clearly the thoughts around your current desires. Twenty minutes of writing non-stop is surprisingly therapeutic.

- Set measurements to judge each experiment by.

Community: Be With Those Who You Want to Want Like

“Would a musician feel flattered by the loud applause of his audience if it were known to him that, with the exception of one or two, it consisted entirely of deaf people?” –Arthur Schopenhauer

“It’s easier to rebel when it feels like an act of conformity.” –Adam Grant, Originals

It’s easier to be a vegan if you live in a Buddhist monastery than if your dad’s a butcher.

Once you know what you want to want you need to surround yourself with people who want to want similar (or complimentary) things. This is because of “mimetic desire” — basically, we want things other people want. A large part of any person’s attraction is that other people are attracted to them.

Use mimetic desire to your benefit by surrounding yourself with people who already want what you want to want.

If you want to want to be a little less obsessed with making money then volunteer at a soup kitchen. If you want to want to work out then join a CrossFit gym.

Using communities to help support what we want to want is not turning our back on self-trust or our internal scorecards. It’s simply putting ourselves in situations where those things become more doable. We’re not relying on others to tell us what to want; we’ve decided on our wants ourselves, and once we start down our self-chosen path, we allow other people to support us on the journey.

Ultimate freedom has been held up as the goal for so long that we nearly forgot about the benefits community constraints can bring with them.

Conscious Constraints

We introduced the idea of anomie in the introduction; this societal normlessness might be one of the most insidious forces facing us today, and engaging with a community is our most potent weapon to battle it.

Jonathan Haidt has a great description of anomie in The Happiness Hypothesis:

“Anomie is the condition of a society in which there are no clear rules, norms, or standards of value. In an anomic society, people can do as they please; but without any clear standards or respected social institutions to enforce those standards, it is harder for people to find things they want to do. Anomie breeds feelings of rootlessness and anxiety and leads to an increase in amoral and antisocial behavior.”

Community can provide rules, norms, and standards of value that are needed to help fend off the rootlessness and anxiety of anomie.

This has been a key to CrossFit’s massive success. It’s not just being more fit that people get addicted to. It’s entering a community in which everyone has the same aim and has committed to follow the same process to head that way. There are clear ways to gain honor and respect: lower your times, lift more, get your name on the chalkboard.

The community you pick will shape you to a degree nearly impossible to appreciate, so it’s important to pick well. It’s important to know what you want to want so you don’t end up in a community that has you wanting the opposite.

Be Picky About Who You Spend Time With

The Amish have mastered this. As a community they are relentlessly focused on what they want to want and using their community to help solidify these wants in each other. William Irvine discusses this in On Desire:

“One of the primary concerns of the Amish is to keep their social desires in check. Most of us seek personal aggrandizement. We want others to notice, respect, or admire us. We might even want others to envy us. These social desires, to a considerable extent, rule our lives. They determine where we live, how we live, and how hard we work to maintain our chosen lifestyle. The Amish are just the opposite. They don’t dress to impress, they dress to conform. …Likewise, Amish buggies look the same because no one wants a buggy that stands out. Non-Amish Americans work hard to keep up with the Joneses; the Amish, on the other hand, work to keep down with the Joneses.”

Even if what we want to want is different from the Amish, their commitment to shaping their community is worth mimicking. We have to treat our exposure to others with extreme care while examining what we want to want. Almost everyone you encounter will tell you — directly or indirectly — what to want; make sure it’s something you want to want.

The Stoic philosopher Seneca likens this to a disease:

“[J]ust as at a time of an epidemic disease we must take care not to sit beside people whose bodies are infected with feverish disease because we shall risk ourselves and suffer from their breathing upon us, so in choosing our friends for their characters we shall take care to find those who are the least corrupted: mixing the sound with the sick is how disease starts.”

This isn’t a call to cut off connection with anybody imperfect (it’d be just you and Jesus hanging out), it’s something to work towards. Seneca continues:

“But I am not enjoining upon you to follow and associate with none but a wise man. For where will you find him whom we have been seeking for ages? In place of the ideal we must put up with the least bad.”

How do we measure “the least bad”? How do we deal with others whose wants aren’t those we want to have? Bob Dylan and the Pope have some ideas that are useful here.

The Possibility of Wanting Upstream in a Downstream World

I met someone recently who is living in northern Missouri without electricity or any modern tools. He and a small group of people are disgusted by society and want as clean of a break as possible. It sounds to me like a lonely, hateful endeavor.

We all feel societal pressures that seem unhealthy. Anyone can look around and see how far the world is from ideal. (Even though we’ve barely spent any time defining “ideal” in the first place.) But the answer for most of us isn’t to run away to the middle of nowhere or head off to a monastery.

We need a community that can help shape our wants, while remaining capable of engaging in society at large.

Pope Francis recently addressed this:

“Nobody is suggesting a return to the Stone Age, but we do need to slow down and look at reality in a different way, to appropriate the positive and sustainable progress which has been made, but also to recover the values and the great goals swept away by our unrestrained delusions of grandeur.”

It’s possible to swim against society’s common default wants without the need to climb out of the stream altogether.

It’s possible to accept, and learn from, the mis-wants of others, without feeling pressured to adopt them for yourself.

Bob Dylan’s It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding) has some great ideas for dealing with a society with unhealthy assumptions. The song/poem in full is amazing, but for now let’s take a look at this piece:

While one who sings with his tongue on fire

Gargles in the rat race choir

Bent out of shape from society’s pliers

Cares not to come up any higher

But rather get you down in the hole

That he’s inBut I mean no harm nor put fault

On anyone that lives in a vault

But it’s alright, Ma, if I can’t please him

If we can see where others are coming from and what is shaping their wants, we have a better chance at seeing our own. Most of us (“the rat race choir”) are too tired and too scared to challenge what we want to want (“Cares not to come up any higher”) most of the time. Instead, we want others to go after the same low-hanging fruit that we do (“get you down in the hole / That he’s in”) to validate the game we’ve chosen to play.

We should have compassion for those who are dominated by society’s default desires (live “in a vault”).

And we should have compassion for ourselves when we have times of being too tired to swim against the current, and take the path of least resistance.

It happens to all of us.

Simply asking ourselves what we want to want, and taking the answer seriously, will already set you far apart from the crowd.

Surrounding yourself with those who share similar aspirations – your crowd — will take you even farther. Belonging to a community of like-minded individuals creates a slipstream that makes sticking with your aims much easier, and may even turn what you want to want into your default desire.

Your “I Like.”

Some Tactics

- Pick 5 communities and list 5 desires they create in their members.

- Date for wants. Your significant other will have a huge impact on what you end up wanting; make sure they want (or want to want) what you want to want.

- Go to a church (even if you’re not a believer).

- Create an intentional brotherhood.

- List the 5 people you most like spending time with and the 5 people you least like spending time with. If the reasons for the 5 best are good for what you want, find ways to spend way more time with them (and less with the others).

- Cut people who are outright toxic from your life.

- Read good books (not the most popular, that is, but the most in line with what you want to want.) Especially read biographies, which will help you assemble a cognitive community of historical mentors — a veritable cabinet of invisible counselors.

- Pay attention to the differences in what you want when you’re with different people.

Bringing It All Back Home

Let’s begin our ending with a parable from Anthony de Mello’s The Way to Love:

“A group of tourists sits in a bus that is passing through gorgeously beautiful country; lakes and mountains and green fields and rivers. But the shades of the bus are pulled down. They do not have the slightest idea of what lies beyond the windows of the bus. And all the time of their journey is spent squabbling over who will have the seat of honor in the bus, who will be applauded, who will be well considered. And so they remain till the journey’s end.”

Unfortunately, our default desires make us forget to open the shades and appreciate the world we’re moving through.

It is possible to go your whole life thinking yourself a success, only to be on your deathbed realizing that you’ve been squabbling on a bus lit with harsh fluorescent bulbs.

This is why Solon, the wise old Athenian, suggested we “Count no man happy until the end is known.”

When you pay attention to your direct experience and surround yourself with great people you may find the rat within starving.

You may find your “ordinary” life light up as you learn to respect your experience.

Like Confucius, you eventually act rightly in all situations out of spontaneity.

The bickering on the bus will fade away as your attention turns to the closed shade. You’ll open it and witness, maybe for the first time, the beauty society had been trying so hard to make you ignore.

What do you want to want?

_______________________

Want to dig deeper? I’ve expanded this into a full ebook, including frameworks and specific suggestions about what you might want to want. Get access to the entire ebook here.

Kyle Eschenroeder is a writer who has been an entrepreneur, day trader, and whatever else sounded good at the time. He sends infrequent, useful emails–this is the best way to connect. Tweet at him @kyleschen.