This article series is now available as a professionally formatted, distraction free ebook to read offline at your leisure. Click here to buy.

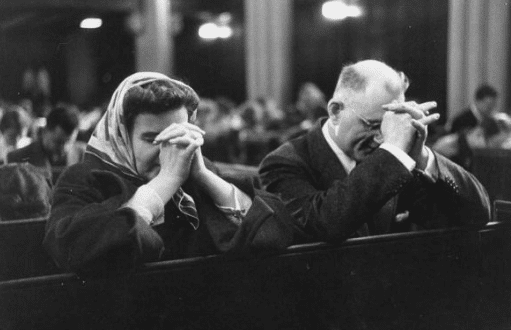

Attend a Christian church service anywhere in the world this Sunday and take a look around at who’s sitting in the seats.

What will you see?

Almost certainly, more women than men. Women with husbands and families, but also married women attending without their husbands, widowed women, and single women, both young and old. You likely won’t see any husbands who are attending without their wives, or very many single guys.

Among the men who are in attendance, you’ll probably notice a couple of characteristics: First, many of the men who are there will be present in body only; you won’t see them singing and they’ll be paying more attention to their phones than the pastor. Second, you’ll observe that the majority of the males adhere to a certain type: white collar, sensitive-seeming, and unfit (either very thin or overweight) — fellows you’d categorize as “nice guys.” You’ll see only a few men who seem to work with their hands, or who you’d describe as athletic, virile, earthy, tough, or rugged.

Pew Research has found that, on average, Christian congregants across the world skew about 53% female, 46% male. In the U.S., surveys show a split that’s even wider: 61% women to 39% men (the gap occurs in every age category, and is thus not due to the fact that women live longer than men). In sheer numbers, what this means is that on any given Sunday in America, there are 13 million more women than men attending church.

In a few Christian churches, the ratio of women to men is close to equal; in others it’s a yawning 10 to 1. The gender disparity is greater in smaller, older, rural, and more liberal mainline churches, and lesser in larger, urban, more conservative, and non-denominational churches, but it shows up in every country, amongst Protestants and Catholics alike, and bypasses no denomination (with the possible exception of Eastern and Greek Orthodox); only 2% of Christian congregations in the U.S. do not have a gender gap.

Men are not only less likely to attend church, they are also less likely to participate in their faith in other ways. According to Pew Research, Christian women are 7% more likely than men to say religion is important to them. And as David Murrow records in his book, Why Men Hate Going to Church, research conducted by George Barna found that women are far more likely to be involved with their church and faith on nearly every level, to the tune of:

- 57 percent more likely to participate in adult Sunday school

- 56 percent more likely to hold a leadership position at a church (not including the role of pastor)

- 54 percent more likely to participate in a small group

- 46 percent more likely to disciple others

- 39 percent more likely to have a devotional time or quiet time

- 33 percent more likely to volunteer for a church

- 29 percent more likely to read the Bible

- 29 percent more likely to share faith with others

- 23 percent more likely to donate to a church

- 16 percent more likely to pray

Barna summed up his findings thusly: “Women are the backbone of the Christian congregations in America.”

So what accounts for this disparity between men’s and women’s commitment to the Christian faith?

You may be tempted to chalk it up to the fact that women are just generally more religious than men. Which is true. Across all religions and around the world, women are 13% more likely than men to say that religion is “very important” in their lives. Several theories, from the biological to the cultural, have been forwarded by researchers to explain this gap, and among the masses, plenty of armchair analysts posit that women are simply more inherently moral or “spiritual” than men.

Yet women’s greater religiosity across all faiths doesn’t at all explain the gender gap within Christianity itself. For as it turns out, it’s the only major world religion with a significant gender disparity among its adherents. Women are only more religiously inclined when surveys of Christians are averaged with those of Hinduism, Buddhism, Orthodox Judaism, and Islam — faiths in which the religious commitment of their male and female members is close to equal.

For example, according to the Pew Research Center, while Christian men participate to a lesser extent in every area of their faith, the commitment of Muslim men and women to their religion is nearly identical, except in one facet — Muslim men are a third more likely to attend services than women. Muslim men and women pray at almost exactly the same rate, and are just as likely to say their religion is important to them.

So it isn’t true that men are less interested than women in all religions — they’re just especially indifferent to the Christian faith.

Again, we return to the question: Why?

Why does a religion started by a carpenter and his twelve male comrades attract more women than men? Christian churches are led predominately by men (95% of Protestant senior pastors and 100% of Catholic clergy are male) and are criticized by feminists as bastions of male patriarchy, power, and privilege; so why is the laity paradoxically composed largely of women?

Was there ever a time when the gender ratio of Christianity was equal? And if so, why did a disparity between male and female adherents develop?

Among men who are committed Christians, why do they seem to be more effeminate, on average, than the male population as a whole? As Murrow puts it, what is it about “Christianity, especially Western Christianity, that drives a wedge between the church and men who want to be masculine”?

These are fascinating questions, certainly for Christians who have noticed this phenomenon themselves and for pastors of churches who are concerned about the health of their congregations (as we’ll see, there’s a strong connection between the number of men in a church’s pews and its vitality).

But it’s also a fascinating subject for anyone interested in the influence of economics and sociology on religion, and who understand the enormous influence religion has had and continues to have on Western culture in general, and conceptions of manhood in particular.

So over the next several weeks, we’ll be offering two articles that explore possible answers to the above questions. First, we’ll outline various theories as to how, when, and why Christianity became feminized and unattractive to many men. We’ll then delve into the history of a time in which there emerged a dedicated response and effort to revive the masculinity of the faith — a movement that went by the name of “Muscular Christianity.”

Stay tuned.

Read the Series

Christianity’s Manhood Problem: An Introduction

Is Christianity an Inherently Feminine Religion?

The Feminization of Christianity

When Christianity Was Muscular

_____________

Sources:

Why Men Hate Going to Church by David Murrow

The Church Impotent by Leon J. Podles