Since the days of Ancient Greece, a battle between two political forces has been going on in the West: democracy vs. tyranny.

But what makes a tyrant a tyrant? How has tyranny changed throughout Western history? And what is its connection to masculinity?

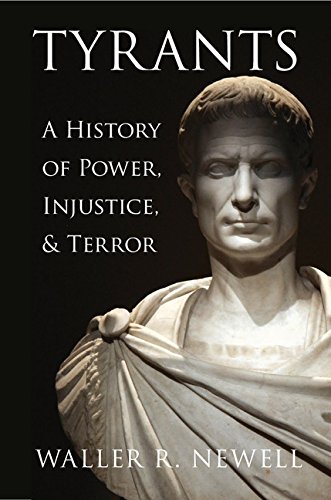

My guest today has recently published a book that explores these questions. His name is Waller Newell. He’s a professor of political science and philosophy at Carleton University in Canada. I’ve had Waller on the podcast before to discuss his great book, The Code of Man.

Today on the show, we discuss his latest book, Tyrants: A History of Power, Injustice, and Terror. Waller and I talk about the three types of tyranny that pop up in world history, what we can learn about tyranny and masculinity from the Ancient Greeks and Romans, how some tyrants paved the way for liberal democracies, how ISIS is a form of modern tyranny, and what the antidote to tyranny is. This is a fascinating show with lots of implications for today’s geopolitical environment.

Show Highlights

- How the traditional idea of manliness in the West includes being involved in public affairs

- What is tyranny?

- How the history of tyranny is the history of its defeat

- What most people get wrong about tyranny

- Why increasing standards of living doesn’t defeat tyranny

- The traits of “garden variety tyrants”

- Why the ancient Greeks allowed tyrants every now and then in their society

- The tension in ancient Greece between heroic masculinity and civic virtue

- How Plato redirected Bronze Age ideals towards the civic good

- The tension between Greek democracy and Persian tyrannical empire (and how the Greeks borrowed ideas from the Persians)

- Why Persian tyrants often allowed for lots of personal freedom for their subjects

- The love-hate relationship the West has had with tyrants since the ancient Greeks

- How the tyrant-hating Romans embraced tyranny

- How reforming tyrants paved the way for modern Western democracies

- The traits of millenarian tyranny and how it developed

- How Rousseau unintentionally inspired millenarian tyranny

- How the violence of millenarian tyrants differs from the violence of garden variety tyrants

- How philosophers like Heidegger and Sartre are the intellectual godfathers of Islamic jihadism

- Waller’s theory on how to defeat millenarian tyrannies like ISIS

Resources/Studies/People Mentioned in Podcast

- The Dream of Scipio

- Winston Churchill

- The Rational Actor Theory of Political Behavior

- Achilles

- A Primer on Plato

- Alexander the Great

- Cyrus the Great

- Thucydides

- Battle of Carthage

- The First Citizens of Rome

- Machiavelli

- The Jacobin Terror

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau

- Martin Heidegger

- Jean-Paul Sartre

Tyrants: A History of Power, Injustice, and Terror is a super fascinating read. You basically get a political history of the West all the way from ancient Greece to today. If you want a better understanding of what’s going on in today’s volatile geopolitical world, Tyrants is a must read.

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Podcast Sponsors

Mack Weldon. Get great-looking underwear and undershirts that eliminate odor. Use discount code “AOM” for 20% off your first purchase from Mack Weldon.

Harry’s. Upgrade your shave without breaking the bank. Use code MANLINESS at checkout for $5 off your first purchase.

Fracture. Rescue your photos from the digital ether by printing them directly on to glass with Fracture. Get 10% off your first order by visiting fractureme.com/podcast. In the survey, let them know you heard about them from the Art of Manliness.

Read the Transcript

Brett McKay: Welcome to another addition of the Art of Manliness podcast. Since the days of Ancient Greece a battle between 2 political forces has been going on in the West, Democracy versus Tyranny. What makes a tyrant a tyrant? How has tyranny changed throughout western history? What is its connection to masculinity? My guest today has recently published a book that explores these questions. His name is Waller Newell. He’s a professor of political science and philosophy at Carlton University in Canada. I’ve had Waller on the podcast before to discuss his great book, “The Code of Man”. If you haven’t listened to that episode check it out, really good show.

Today on the show we discuss his latest book, “Tyranny: A History of Power, Injustice and Terror”. Waller and I talk about the 3 types of tyranny that pop up in world history, what we can learn about tyranny and masculinity from the ancient Greeks and Romans, how some tyrants pave the way for little democracies, how ISIS, or ISIL whatever you want to call it, is a form of modern tyranny and what the anecdote to tyranny is. This is a fascinating show with lots of implications of today’s geopolitical environment, so get a lot of insights. After the show, make sure to check out the show notes at aom.is/tyranny.

All right, Waller Newell, welcome back to the show.

Waller Newell: Nice to be with you, Brett.

Brett McKay: Well, so last time we had you on we were talking about your books on Manhood, The Code of Man, what is a man. You got a new book out about the history of tyranny. I’m curious, how does this book, the History of Tyranny, continue your work about manhood and masculinity throughout the west? How is it a continuation of what you’ve been doing for the past couple of years?

Waller Newell: I’ve always stressed that the traditional conception of manliness has quite a bit to do with an interest in public affairs. If you go back to the classical notion of the Kalos Kagathos, the gentleman, Aristotle for example says that prudence, the hallmark of great statesman is the highest virtue short of philosophical contemplation. In Cicero’s Dream of Scipio, for example, you have this model of a balance of civic virtue and the life of the mind, and that civic virtue is higher than battle field courage. This whole notion of an interest in public affairs continues throughout the Renaissance with Civic Humanism. If you think of the American founders, they read classics like Cicero, Polybius, Sallust in college. They emphasized that you must always prefer Cato to Caesar. As Alexander Hamilton said, you must always prefer the servant of the Republic to the dictator.

These lessons, I think, became very real and very formative for the American political tradition as well. I’d also mention the notion of the tremor, the notion of tactical flexibility for a long term goal in politics. Churchill, for example, said that Abraham Lincoln was the classic tremor. I think that whole notion of an involvement in public affairs as a part of what it means to be a man, but at the same time avoiding extremes and trying to plot a kind of moderate course.

Brett McKay: Got you. Your new book, the History of Tyranny, it’s called Tyranny, talks about the history of Tyranny. I’m curious, how do you define tyranny and why write a history of this form of government?

Waller Newell: Well, tyranny is both a form of rule and a kind of psychology. At bottom, tyranny is lawless rule by an individual or by a group. It treats people as if they were objects for manipulation with no rights of their own and no right to a say in how society is governed. Why did I write it? Well, I would point out that the history of tyranny is also the history of its eventual defeat by free self-governing societies. It’s not a pessimistic account. In a way it’s a hopeful one. You can go all the way back to the Greeks, think of their 3,000 tiny city-states versus the huge multinational Persian empire, the Battles of Marathon, Thermopylae, Salamis. This confrontation, or struggle, between democracy and tyranny has been repeated many times. Think of Waterloo, Dunkirk, the defeat of Hitler, the defeat of the Soviet Empire. Tyranny has always been with us, and we have to be alive to that danger. At the same time, so far, tyranny as never succeeded in prevailing.

Brett McKay: What do you think most modern, western democrats, right, democracy, people who live in democracy, what do you think they get wrong about tyranny?

Waller Newell: I would say to some extent that we’re victims of our own success. In other words, because we do live in comparatively peaceful historically, unprecedentedly wealthy societies where the rule of law is the norm, maybe we don’t always live up to it, but it is the norm, I think that can lull us into a kind of amnesia whereby we forget that this way of life has been successful mainly in the west. We have a tendency however to project it on the rest of the world and to convince ourselves that everybody is that way or is on the verge of becoming that way. I think it’s reflected in what is sometimes called the rational actor theory of political behavior, which is that people are motivated primarily by material self interest, and that if you can provide them with material prosperity, their aggressive impulses will fade away. That might work in the west. It took us 400 years to cultivate those values of individualism. I think history shows that it’s at least doubtful that people everywhere in the world are motivated solely by a desire for economic prosperity.

Brett McKay: Yeah, and we’re going to talk about that later on, because you make the case that what we’re seeing with the Islamist Jihad and ISIS, it’s a form of tyranny. We’ll talk a little bit more about that later on. Let’s talk about the types of tyranny that you argue exist. The first one you describe in the book is Garden Variety Tyrants. What are the traits of Garden Variety Tyrants?

Waller Newell: Well, I would say that this is at once the oldest form of tyranny and one that is still everywhere around us today. Garden Variety Tyrants rule an entire society, you might say, as if it were their own private property to exploit for themselves, their families, their cronies. Sometimes this involves immense personal hedonism and luxury. Think of these notorious Roman Emperors like Nero, Caligula. It’s really something that stretches back from Hiero of Syracuse to the Somozas of Nicaragua or Bashar Al Assad today. By the way, Plato would’ve instantly recognized Assad as this kind of tyrant.

Now, these figures can do some good. The Greeks sometimes gave power to tyrants sort of like a show gun, someone more effective than a traditional monarchy at winning wars, improving the city’s economy and defenses, but of course they always had to be on guard because at the end of the day these people really do treat an entire society as if it were their personal property to exploit.

Brett McKay: That is going back to the ancient Greeks and kind of exploring the idea of Garden Variety Tyrants, it was a great section. It was one of my favorite sections that was in the book, kind of exploring the connection between Greek ideas of masculinity or manliness and politics. It seemed like there was this tension in Greece. On the one hand they had this heroic ideal from Homer where it seemed like the Garden Variety Tyrant was sort of set out as an ideal. You had this chieftain who had his kingdom and he treated his kingdom as if the people were part of his family. Then you had thinkers like Plato and Aristotle who were saying they were trying to put a check on that compulsion. Can you talk a little bit about that tension that existed within Greek culture itself about the roll of tyrants and how masculinity effected it?

Waller Newell: Yeah. It is quite fascinating because in a way Homer’s Achilles was the ideal of Greek manhood. He was a kind of Bronze Age Chieftain, a king in his own right, almost like a Viking chieftain in a way. He would lead his men into battle personally. It was also a lesson in the danger of supreme personal ambition and how it had go awry. It’s his rage over a perceived insult from his commander in chief that sparks the entire Trojan war. It’s terrible bloodshed. Everything is about him. He’s a kind of narcissistic figure. He’s magnificent but he’s flawed. Yet, even when the Greeks themselves sort of went beyond their Bronze Age heritage and became self governing city-states, they no longer had Bronze Age hero kings like Achilles, but they still idolized Achilles. That’s the tension that they were living as free societies where in fact an Achilles could never really be part of the constitution and yet a lot of young men still looked up to Achilles as this ideal.

Plato’s answer is to try and redirect Achilles kind of ambition from personal power and glory to the honor that you derive from serving the common good in cooperation with your fellow citizens. For this you need a new education in moderation and self control, something that is very unlike Homer’s depiction of heroism. In a certain sense, Plato’s republic is all about how to forestall Achilles from emerging.

Brett McKay: Okay. Beside … Oh go ahead.

Waller Newell: I should correct myself. I shouldn’t have said by the way that Achilles rage sparked the Trojan war. That was because of the abduction of Helen, but it was certainly his rage that prolonged the war because he withdrew in a huff from the fighting. That made victory for the Greeks take a long time to come.

Brett McKay: Got you. You had this tension within Greek culture itself where they had this ideal of personal ambition with the Homeric poems, but then trying to control that ambition to serve the greater good, to serve the polis. Besides that tension there was a tension between Greek culture itself and the East, or Persia. People always talk about, ‘Oh yeah, the Greeks, Persia was their enemy. They thought them as weirdos”. They actually got a lot of inspiration from Persia and borrowed a lot of things. Can you talk about the tension between Greek culture itself and Persian culture and how they combined the two sometimes to create tyrannical governments?

Waller Newell: Yeah. In the west you had this tradition going back for quite a long time of small self governing city-states. In the east, by contrast, you had huge multi-national empires, powerful, wealthy, huge standing armies. In a way it was a form of rational despotism. If you think of the Pharaohs the Babylonians, Cyrus the Great, these were prosperous, powerful societies. They were well run. The Greeks were impressed. They were impressed by the Persian Empire even though they feared that it was trying to extinguish their freedom.

Basically when Alexander the Great conquered the Persian Empire, it was as if Achilles had taken over a world state because Achilles was one of those many … Excuse me. Alexander was one of those many young men who admired Achilles. Alexander then used that captured world state to spread the values of Greek culture everywhere. I think there was this really important synthesis between you might say the Greek heroic standard of manliness, but at the same time they really learned an awful lot from the Persian Empire. In a certain sense they took over the legacy of the Persian world state and Hellenized it.

Brett McKay: How would describe the Persian Empire? Was it a tyranny? The way you describe it is that yes they conquered people but then it seemed like the leaders would give their subjects a lot of leeway in terms of their religion, how they governed themselves. What would you call it, is it just despotism? What’s going on there?

Waller Newell: Strictly speaking from a Greek perspective you would have to call it a tyranny because there was no form of representative government. The Persian king was a master. The word in Greek despotes literally means that he had the power of life and death over every single member of his empire from the highest lords to the lowest peasant. He could dispose of them as he wished. Yet at the same time the power of that state when properly used by people like Cyrus created road systems, promoted the economy, promoted trade and Cyrus began the Persian tradition of extraordinary tolerance of religious diversity. Cyrus famously rebuilt the temple in Jerusalem. He encouraged the subject peoples of his empire to retain their religious faith. He made no intent to interfere. He also encouraged people to rise on their merit, his own elite became multinational. In many ways Cyrus the Great was the paradox of a liberalizing despot. By the time the Greeks encountered his successors, the Persian Empire still had many of those qualities.

Brett McKay: I think that was an interesting point you made throughout the book is that, I think what a lot of modern individuals who live in the west get wrong about tyranny is that a lot of times people preferred tyranny over Republicanism, because as you said there’s a lot of freedom. They did things to improve the lot of their subjects. I’m curious, when did the idea that tyrants were completely bad, like you would never want a tyrant, you would prefer individual government, individual liberty? When did that take hold in the psyche of the west?

Waller Newell: That’s an interesting question. I would say that that particular sort of hatred of tyranny is present from very early on. In Thucydides for example, the story of Harmodius and Aristogeiton and later peoples profoundly mixed feelings about Julius Caesar, some of whom saw him as a tremendous benefactor for the common people of Rome, but others who absolutely loathed and despised him as a tyrant who wanted to crush Roman liberty. The interesting thing about the Greco-Roman heritage is that it had all of these nuance judgments about tyrannical rule. There were good and bad varieties. There were more preferable versions, less preferable versions.

The Romans at bottom had a totally uncompromising intolerance for the notion of even a monarchy, let alone a tyrant. In fact, for the Romans the word “Rex”, king, was simply another word for tyrant. That’s how fiercely resistant they were to any form of non-Republican authority, and yet even they … I mean think of how the debate to this day about how we think of Julius Caesar, we’re still debating this right? There are people who see him as a tremendously beneficial figure and others who just excoriated him as the death of Roman liberty.

Brett McKay: Yeah. That’s interesting. Speaking of the Romans, how did they go from the Republic where they just loved individual liberty, they abhorred kings or any type of monarchy or a tyrant, how did they transition to an empire that was led by a tyrant?

Waller Newell: This is one of the most fascinating stories, I think, in political history. Really you can say after the defeat of Carthage, Rome woke up one day and found itself the master of the world. Yet, it was still in effect a small Greek city-state. It was a self governing city-state in possession of an empire. The way that they got around this was because they had such a fierce aversion to monarchy they pretended that the emperors, beginning with Augustus, were merely the first citizens in what was supposedly still a free Republic, the city-state. It was a Hellenistic monarchy outwardly garbed in the traditional forms and rituals of a Republic. That was, you can say, sheer genius in a certain way that they managed to contain that contradiction by that kind of constitutional fiction in a sense.

Brett McKay: We just talked about Garden Variety Tyranny. The second class of tyrants you look at are what you call Reforming Tyrants. What are their traits and what are some notable examples of Reforming Tyrants in western history?

Waller Newell: Well I think some of the ones I mentioned like Alexander, Julius Caesar, Augustus, these are people who want complete power and glory for themselves, but they want it at least in part to do good things for their people. They build roads, they build sewers, they beautify their cities. They distribute land to the poor. Unlike a lot of Garden Variety Tyrants these sort of hedonists like Nero, they often have a very strong degree of self control. They are able to master their passions for the sake of this long term goal. Then if you turn to the modern age you can look at these modern state building despots, as I call them, who aim to crush the church, centralize authority under the secular state, the Tudors, Louis the XVI, Frederick the Great, Peter the Great, Napoleon, I think they all fit into this category.

Brett McKay: Yeah, and speaking of, I thought it was really interesting is that you make the case that these enlightenment ideals of individual liberty, the consent of the governed were actually made possible by reforming tyrants like the Tudors and Henry … Can you explain, how did tyrants pave the way for individual liberty and sort of self governance?

Waller Newell: It’s an interesting story. It’s full of paradoxes. You can basically say that Europe followed two paths to modernity, following I would say Machiavelli’s script. Machiavelli said the state could be ruled effectively either by peoples, meaning Republics, or by princes. The goal of either was to maximize the security and well being of all. Now in England and America self government evolved more or less peacefully, not entirely so. There were civil wars, but compared to Europe, more or less peacefully. By the time the constitutional governments were formed the values of individualism and commercials of interest were already very deeply rooted. Now in Europe by contrast the forces opposed to modernity, the aristocracy, the church, remained very much stronger and more formidable so that their society had to be modernized from the top down, but with the same ultimate goals in mind.

You think of Napoleon. Napoleon exported liberal values through his conquests, self government, religious toleration, more rights for women, meritocracy. By the 19th Century, I would say that having taken these two very different paths, Europe and America met in the same place.

Brett McKay: Got you. Then also you talk about how the top down reforms took place in Russia as well with Frederick the Great and the like.

Waller Newell: Absolutely. They saw themselves as creating societies where the individual would be liberated. They sincerely saw themselves as wielding power to bring about modern societies in which the law of the average person would be improved.

Brett McKay: Did they still want to maintain power?

Waller Newell: Oh, absolutely.

Brett McKay: Right. You can’t take the tyrant out of the tyrant.

Waller Newell: They were often supremely ambitious people or very militaristic like Frederick the Great. I mean he spent half his life in the saddle. They often wanted to enlarge their domains. They wanted bigger countries to modernize, and that was a part of the paradox. They certainly did not believe in democracy or self government. They might’ve wanted to help improve the lot of the average person, but they were definitely going to remain in the driver’s seat.

Brett McKay: Here’s another question I think is important. Are these classes of tyrants, are they mutually exclusive or is it possible to have shades of all three, so you can be reforming tyrant but still be a garden variety tyrant as well?

Waller Newell: I think it’s possible to have shades of all three. They’re not fixed distinctions. They kind of blur into each other on occasion. I would say somebody today, like Vladimir Putin is a combination of all three. I would describe him as a kleptocrat and a reformer with a side dish of millenarianism.

Brett McKay: Okay. Speaking of millenarianism, the third type of tyrant, third class is called Millenarian Tyrants. You argue that this type of tyranny is a modern development. What sets it apart from the other two types of tyranny and how did it develop?

Waller Newell: What I think sets it apart starting with the Jacobin Terror of the French Revolution in 1792, was the attempt to return to what the Jacobins called the year one, a golden age of alleged complete equality, no property, no classes and the individual submerged in the collective of a totalitarian state. In other words it was an attempt to create utopia on earth over night. It begins as I said with Robespierre. Robespierre thought he was bringing about Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Golden Age, the state of nature when we all lived in bliss and equality. I think starting here as well is that there’s always a group, some race or class that stands in the way and has to be exterminated so that all mankind can live in bliss forever. For the Jacobins it was the bourgeoisie and the aristos. For Lenin and Stalin it was the kulak, or so called rich peasant. For Hitler it was the Jews. I’m arguing that this line of descent runs from the Jacobins to the Bolsheviks, the Nazis, Chairman Mao, the Khmer Rouge and Jihadists groups today like ISIS.

Brett McKay: That’s interesting that Rousseau was kind of the guy. Did Rousseau, did he advocate for this sort of thing, this sort of return or did individuals read his work and they were like “We’re just going to actually make that happen”?

Waller Newell: I think it’s more the latter. A fair reading of Rousseau probably would make you conclude that he didn’t intend that sort of outcome. On the other hand, his rhetoric was very inflammatory. Property is theft, man must be forced to be free. When someone like Robespierre came along he could cherry pick those inflammatory phrases and convince himself that he was bringing about Jean-Jacques dream of the state of nature in the here and now.

Brett McKay: Got you. Part of the Millenarian Tyrant’s tactic is to cleanse the earth, use mass killing to cleanse the earth so they can get back to this, what you call history behind the history. Garden Variety Tyrants and Reforming Tyrants would also kill thousands or hundreds of thousands of people to further their agenda. How does the violence of Millenarian Tyrants differ from Garden Variety Tyrants and Reforming Tyrants?

Waller Newell: It’s a fair point. I would first point I guess to the shear scale of the violence. In other words in a mere year and a half during the Jacobin Terror in France, something like a quarter of a million people were killed. Of course, later on with full blown Totalitarianism that became millions and tens of millions of people. The methodical slaughter of entire races and classes, what is sometimes referred to as the Industrialized murder of the Holocaust, I would say this began with the Jacobins too because the Jacobins did not kill randomly. They liquidated entire groups of people. They began the whole litany of horrors of mass firing squads and pits. They sometimes just opened fire with cannons on people. It was really the kick off to what became all to familiar in the 20th Century. I’d also say that it’s different from other kinds of tyrannical violence because of this genocidal component.

In other words, if you’re a member of the designated race of class standing in the way of Utopia, you’re going to be killed whether you oppose the regime or not, even if you support it. That’s not true of ordinary tyranny I think. Assad kills people because they threaten his monopoly on power. If you give in you won’t be killed. If you were a Jew willing to give into Hitler, you’d still be killed, just as ISIS will kill you if you are a Christian. I think that’s an important difference.

Brett McKay: Okay. Yeah, you make the provocative argument that Islamist Jihadism that we’re seeing with Al-Qaeda, ISIS, et cetera get most of it’s inspiration from Rousseau, Heidegger, Sartre and these existential philosophers rather than Islam. Islam is a component of it but the inspiration of what they’re doing comes from these existential philosophers and Rousseau. Can you explain that a bit, that argument you have?

Waller Newell: Yeah. I’m basically arguing that the notion of an authentic people of destiny, which Heidegger identified with national socialism, makes a migration from the far right to the far left under neo-Marxist thinkers like Sartre so that the proletariat of classic Marxist theory is now replaced with this notion of the people and the destiny of the people. Now as to its connection with Jihadist ideology , first of all I’d say that it’s pretty well documented. I try to show it in the book. Other scholars like Bernard Louis have made the same sorts of connections. Just to take one example, the intellectual god father of the Iranian Revolution, Ali Shariati, studied in Paris and was influenced, we know, by Sartre, and Heidegger, just like Pol Pot by the way at roughly the same time.

I think that it’s important that we understand the extent to which Jihadist ideology is really in my opinion a totalitarian ideology that is masquerading as a religious movement.

Brett McKay: Why is it important that western democracies understand that Jihadism is a strand of Millenarian Tyranny?

Waller Newell: I think it’s important because we need to bare in mind that Islam, traditionally, doesn’t believe that man can create a perfect society on earth through his own efforts, especially not through secular revolution.

Brett McKay: Great. Well, Waller Newell, thank you so much for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Waller Newell: My pleasure, Brett. Thank you for having me.

Brett McKay: My guest today was Waller Newell. He is the author of the book Tyranny. You can find that on amazon.com and bookstores everywhere. Also make sure to check out the show notes at aom.is/tyranny for more links to resources where you can delve deeper into this topic.

Well, that wraps up another addition of the Art of Manliness podcast. For more manly tips and advice make sure to check out the Art of Manliness website at artofmanliness.com. If you enjoyed this show I would really appreciate if you would give us a review on iTunes or Stitcher, or recommend us to a friend. It goes a long way. As always, thank you for your continued support. Until next time this is Brett McKay telling you to stay manly.