With our archives now 3,500+ articles deep, we’ve decided to republish a classic piece each Sunday to help our newer readers discover some of the best, evergreen gems from the past. This article was originally published in July 2016.

As a boy I followed the Dallas Cowboys, and one of the players I really admired was Herschel Walker. He was a beast, but the guy could move like nothing else.

A few years ago I read somewhere that Walker’s legendary, granite-like physique was built not by lifting weights but through bodyweight exercises — lots of them. On the order of 2,000-3,000 push-ups and sit-ups every day.

Talk about an intriguing regimen! I wanted to learn more about it. How and why did Walker develop this program for himself? What underlay his fitness philosophy? Were sit-ups and push-ups all he did, and if not, what other kinds of exercises did he do?

I searched online, and while I couldn’t find more details, I discovered that Walker was an even more impressive athlete than I had imagined and a true fitness renaissance man: he had excelled in both track and football in college, earned a 5th degree black belt in taekwondo, competed as an Olympic bobsledder, and even danced with the Fort Worth Ballet. Oh, and he’s continued his insane bodyweight workout into his 50s, in addition to training for MMA.

Now I really wanted to know the full nature and motivation behind Walker’s unorthodox training program. I was able to finally discover it by getting my hands on a copy of Basic Training, an out-of-print book he wrote in the 80s along with Dr. Terry Todd, an Olympic weightlifter and conditioning expert. The book remains so sought-after that thirty years after its publication, used copies continue to command a crazy premium.

Below you’ll find the background on how Walker developed the unorthodox bodyweight training program he’s been doing for over forty years, as well as details as to what it consists of. The Walker Workout is definitely not for everyone, but its exercise components are in many ways the least interesting thing about it. Walker’s story and overall fitness philosophy — one that eschews excuses and convention, and prizes autonomy, improvisation, experimentation, and consistency — offer interest and inspiration for all.

The Origins of Herschel Walker’s Bodyweight Workout

Walker grew up on a farm in rural Johnson County, Georgia along with six siblings. While his family didn’t have a lot of money, they got by, and his household was filled with plenty of love and support.

As a boy, Herschel had a speech impediment, was short and chubby, and didn’t seem destined for athletic greatness. In running races with siblings and playing games with friends, he was slow and uncoordinated, struggled to keep up, and felt lacking in the confidence and endurance to really push himself. In elementary school, he was bullied and beat up by his classmates, and thus often chose to stay inside during recess rather than going out to play.

After finishing the sixth grade, Walker decided he wanted to turn things around for himself. He approached a track coach who had mentored his older brothers and told him he “wanted to get bigger and stronger and faster and be better at sports.” As Walker remembers, the coach responded that “it was simple but I had to work hard at it. He said to do push-ups, sit-ups, and sprints. That’s all he said. But it was enough.”

Herschel went home and got started on his new bodyweight program straightaway; his parents had always taught him that “you can’t make excuses in life, you’ve got to get it done,” and he thus made do with what was available:

There weren’t any weights then at school, of course, and we sure didn’t have any out in the country, but I used what I had, and that was the living room floor and the dirt road that ran from the highway out front up the hill to our house. I did my push-ups and my sit-ups on the floor most of the time, and I did all my sprints up that hill out front.

Herschel’s commitment to his workouts was religious — he never missed a day. He would crank out his push-ups and sit-ups during TV commercial breaks at night, and did his sprints on the hills and fields near his home — even in the summer, under the hot Georgia sun. He particularly liked to run when his father had recently plowed up the ground, as the consistency of the dirt became like heavy sand and added an extra challenge. He’d also chase and run alongside the family’s horse and bull, changing direction as the animals did in order to develop his agility and reaction time. There was a chin-up bar out back and he added chin-ups and pull-ups to his routine as well.

While perfect pushups, chin-ups, sit-ups, and sprints formed the core of Walker’s workout, they were hardly the only exercises he did. Herschel did different bodyweight exercises like squats and dips, loaded hay and performed other chores around the farm, wrestled with his brothers, took up taekwondo, played tennis with friends, and even practiced for and entered dance competitions with his sister. He later theorized that this diversity of activity contributed greatly to his athletic success (something that’s been born out by recent research):

I think I developed as well as I did because I did so many different things — so many different kinds of exercise. I can’t prove it, but I think when you hear someone telling a young athlete to specialize and concentrate on only one sport you’re hearing someone give bad advice. I believe just the opposite. I believe variety is best…any kind of movement can help you learn about lots of other kinds of movement. That’s why I do so many things myself and that’s why I believe all young people ought to do as many different sports and types of exercise as they can.

Walker in fact didn’t play his first organized sport – basketball — until 7th grade. He started doing track and field in 8th grade, and only began playing football in 9th. He continued all three sports throughout high school, while still continuing to do his personal bodyweight workout each day on his own.

(It’s worth noting that while Walker was committed to athletics, he was equally diligent about succeeding in school, strictly setting aside at least two hours a night to do his homework; for his efforts, he became valedictorian of his high school and president of its honor society, an accomplishment, he says “I was as happy about as I was about the good things that happened to me on the football field.”)

Willing to put in 110% effort day after day, Walker filled out, got faster, and improved his athletic skill; it wasn’t long before he was excelling in all three sports and beating the kids who had formerly surpassed him:

What a good feeling that was, too, to know all that hard work was paying off, and to know that even though I wasn’t all that good to begin with, I could get better. I remember a bunch of kids I grew up with who had a heap more talent than I had but who never trained much or tried very hard. I’m not saying they didn’t try at games, but almost anybody’ll try hard in a real game. What matters is how hard you try before the game, especially when nobody is watching you. That’s what’s important. If you can bear down and really train and try hard before the game, the game’ll take care of itself.

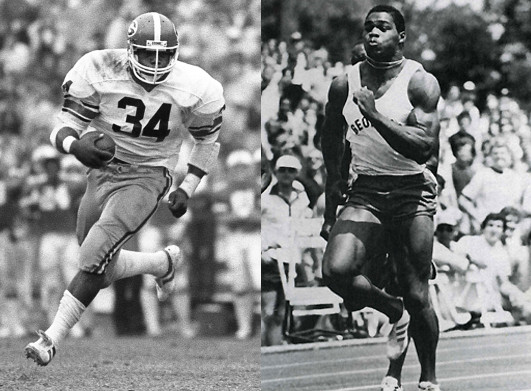

Walker was a versatile, standout athlete in high school. In track, he won the state championship in the shot put and the 100- and 220-yard dash, and anchored the victorious 4X400 relay team. In football, he rushed for 3,167 yards his senior year and led the team to their first state championship.

This dual success continued at the University of Georgia, where he became an All-American in both track and football, helped the Bulldogs win the Sugar Bowl as a freshman, and won the Heisman Trophy as a junior.

Walker played sixteen seasons of professional football, the first three with the now-defunct United States Football League. In the NFL he racked up massive rushing yards (18,168 all-purpose yards, the ninth all-time best) while playing seven different positions. Combining those yards with those he garnered in his years playing for the USFL would put him first on the NFL’s career rushing list.

In 1992, while Walker was still playing pro ball, he competed in the Olympics, placing 7th in the two-man bobsled competition.

In more recent years, he’s tried his hand at MMA, winning the two bouts he participated in by TKO. Walker felt his MMA training left him in better shape at age 50 than when he was playing football in his early 20s.

And all along, up until the present day, he’s kept up with the bodyweight workout he first starting doing in junior high. In fact, he didn’t start lifting weights until several years into his professional football career. It’s not that he had anything against it, but he had seen improvements in his strength and speed every year since high school, and figured he’d only start lifting once those gains ceased. After his football days were over, he returned to a bodyweight-only program, as he believes it protects the joints and promotes fitness longevity.

So what exactly was included in a program that allowed Walker to become a standout high school athlete, one of the best college football players of all time, and a leading rusher for the NFL, as well as spend his career nearly injury-free and maintain his fitness into his 50s?

Let’s take a look.

The Philosophy & Elements of the Walker Workout

Even though Walker didn’t lift weights in college, when the team did a bench press test, he hoisted an astonishing 375 lbs (the most, his coach said, anyone had lifted on the BP at Georgia up until that time), and did 222 lbs (his body weight) for 24 reps. While Walker has always denied being born with superior talent, saying all his abilities were due to hard work and his unique routine, he very likely possesses a stellar set of genes. Still, he did a ton to maximize that potential, utilizing a program that incorporated the following elements and underlying philosophy:

Massive reps. From middle school up through middle age, Walker has done thousands of push-ups and sit-ups nearly every day. Such a massive number of reps isn’t typically recommended to build strength, as your body adapts to the exercise, but Walker found a way to keep on making gains in his fitness by infusing his workouts with a whole lot of:

Variety. From martial arts to dance, Walker engaged in a wide range of physical activities and exercises throughout his life, and continues to do so. As he told nfl.com, “I was doing CrossFit before they gave it a name.”

He also was constantly looking for different variations of individual exercises to try, in order to keep them challenging:

I was always trying to find some new way to sprint or some new way to do push-ups or sit-ups to keep my interest up and to make my body work in different ways so it would get strong from every angle.

Oftentimes, Walker simply made up his own variations himself, because he was a fitness renaissance man who constantly liked to:

Experiment. Walker was never one to take conventional advice; instead, he enjoyed trying his own experiments, and seeing exactly what exercises worked uniquely well for him:

The way I usually do things is to try something new and then check it out real good as to how it feels. If it feels good to me — if I think it’s really working me hard — then I’ll add it to all the other exercises I do. But if it doesn’t seem to work the way I want it to, I’ll just let it go. By doing things this way I only do exercises that feel right for me. Everybody ought to try different exercises, too. Just keep experimenting.

Thus Walker freely created his own exercises and workouts — simply going at it ‘til his muscles burned — and assessed their efficacy based on how they made him feel, and the results they garnered.

While those who stick to strict, standard programs might think his routine is nuts and ineffective, Walker simply doesn’t care. Even now, he maintains unorthodox habits: sleeping for just five hours a night, waking up at 5:30 a.m. to do scores of sit-ups and push-ups, eating only once a day (and sometimes fasting for several), and consuming a diet that consists largely of soup, bread, and salad without worrying about his macronutrients; he figures if the “farm strong” men he grew up with never thought about how many grams of protein they were eating, he doesn’t need to either. He just completely does his own thing, treats himself as an n=1 experiment, and lets the results speak for themselves.

Given this level of autonomy, it’s no wonder he’s remained so motivated throughout his life. As Walker put it, “I try, with all my workouts, to make them fun. I like to experiment with different things, and I think that trying new exercises helps to keep you fresh and mentally ready.”

Consistency. Even though Walker is a freethinker when it comes to fitness, his commitment to it is positively dogmatic. He believes in doing some kind of exercise every day and has hardly missed a single workout since he started doing his bodyweight routine as a young man. Consistency, Walker says, is like funding an investment in your body and mind:

I did a lot of the things I did because I loved to do them or because I thought they’d help me get better in the things I thought I could be good at. Basketball was great because I loved it, but I also knew it helped me physically for football. All my other stuff — my exercises and all that — I did because I knew it was good for me. And after I’d work out real hard I always had a good feeling because I knew I’d done what I needed to do to make my body improve. I used to think training was a lot like putting money in the bank. And I don’t say that because I get paid now to run with the football. I say it because of the feeling I got — and still get — from doing my exercises. It makes me feel good about myself, just like you feel when you put away a little money every week and watch it build up.

The Exercises of Walker’s Workout

Here’s how Walker utilized these elements in creating his unique workout routine, and a closer look at the exercises he’s done for four decades:

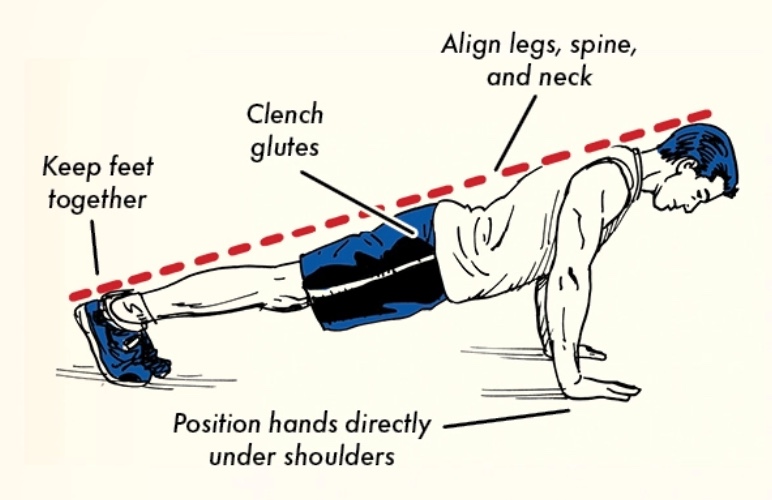

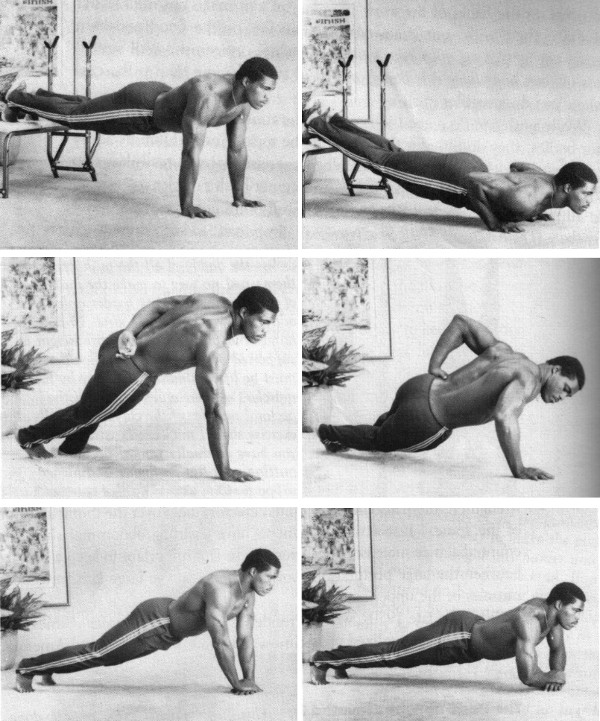

Some of Walker’s push-up variations, as featured in Basic Training. For even more push-up variations (as well as variations for other bodyweight exercises), check out our post on the “Prisoner’s Workout.”

Push-ups. As a chubby adolescent, at first Walker couldn’t do any push-ups at all. He slowly worked his way up to 25 by doing as many as he could in a stretch, taking a 10-15 second break, and then doing some more until he hit that number. Using the same approach, he worked up to doing 50 push-ups a night, then 100. Slowly he increased his reps until he was doing 2,000 a day as a young man. In college he usually did 300 but that was on top of his track and football workouts. Today he claims to do 3,500 push-ups every day (though he keeps them to “just” 1,500 when he’s doing MMA training).

At first Walker stuck with doing the standard, hands shoulder-width apart push-up, but in high school he started incorporating different variations, including doing them with his feet elevated on a chair, with hands together under the chest, one-handed push-ups, and handstand push-ups. He would mix these harder variations in with the standard kind, trying to increase the ratio of harder to easier ones, all the while increasing his overall number of reps.

The way Walker would do his push-up routine was to start by doing them in the standard style, but only go halfway down to the floor — he liked the way these worked his triceps, made him sweat, and increased his endurance. He’d do 150 of these, stopping for short breaks when he got tired. Then he’d do 10-20 reps of the harder variations, then go back to the halfway-down kind, then back to the hard ones, and then finish his floor push-ups by doing standard ones extra slowly. Then he’d end the push-up round of his workout by doing handstand push-ups — sets of ten with short rests between sets, done until he hit whatever his overall rep goal was. After Walker got married, he also threw in 2 sets of 25 standard push-ups, done with his wife sitting on his back.

Sit-ups. Like push-ups, Walker initially had a hard time cranking out sit-ups and could barely do 10. Once he could do that many consistently, he would do sets of ten, with short rests between them, until he reached 50 total reps. Then, he did sets of 10-20 to reach 100 reps. After that he did 50 at a time, for 6 sets, and 300 total reps. Eventually he was doing 3,000, which is about as many as he still does today.

As with push-ups, in addition to the standard sit-up, he did tons of variations: straight-legged, bent-legged, side crunches, leg raises, legs on chair, twists, etc.

Walker also worked his core by playing basketball every day he didn’t play football, concentrating on and doing plenty of turnaround jumpers and layups and putting extra twist in the shots.

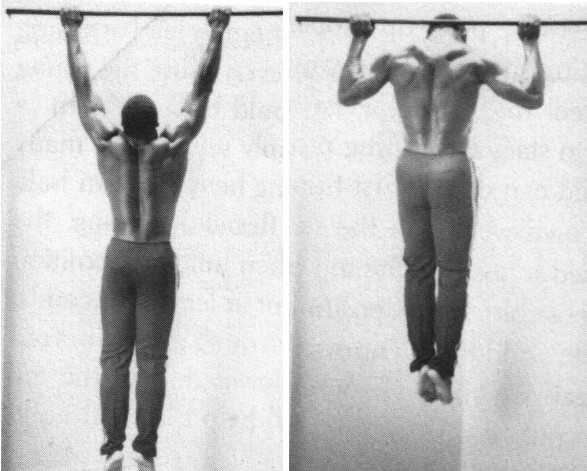

Behind-the-head pull-ups.

Pull-ups/Chin-ups. As a young man, Walker did 1,500 pull-ups a day, alternating between palms facing away, palms facing towards, and pulling up until the bar touched behind his head. When those became too easy, he’d tie a weight plate around his waist, and also do one-armed pull-ups, where one hand holds the bar, and the other grasps the wrist of the hand doing the holding.

Running. Walker believes that “running or sprinting is the most important skill most athletes can have.” His own running most often took the form of sprints — speedy sprints. Truly, at 6’1” and 225 pounds, it’s amazing how fast Walker did and can move his muscular physique; he claims to still be able to run a 4.35 40-yard dash.

Growing up, Walker liked to do hills — sprinting up and trotting down — for the resistance and challenge the incline presented. He added resistance to his sprints in other ways as well — wearing a weight vest, running while holding small dumbbells in each hand, or pulling a tire filled with 25-50 pound weights (dumbbells or shots); the tire was tethered behind him with a 15-foot cord secured to a leather weightlifting belt.

Taekwondo/MMA. Walker took up taekwondo as a young man, sometimes spent an hour a day on his katas (forms) in college, and today is a 5th degree black belt in the martial art. Having been bullied as a boy, he was initially drawn to taekwondo as a way to learn to protect himself, but came to find it an excellent enhancer of all his other athletic endeavors. From taekwondo, Walker gained discipline, balance, coordination, body control and awareness, timing, flexibility, quickness, and the knowledge of how to hit through something and “when to explode on somebody.” He credits it with keeping him loose throughout his football playing days, and today keeps up with martial arts with MMA training.

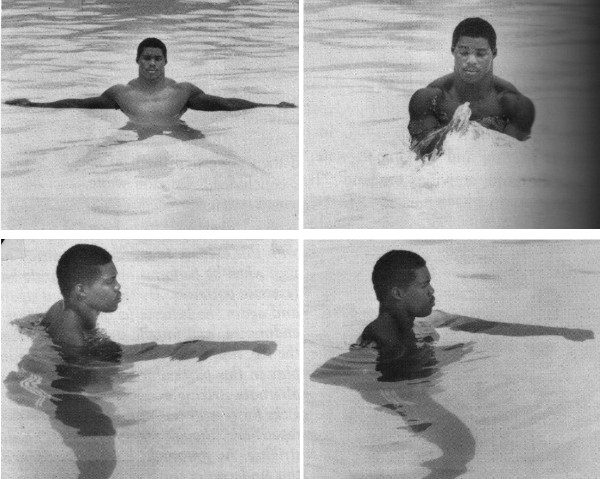

Above: Walker’s “power clap.” Below: “Alternate striking” exercise, in which Walker threw straight punches underwater, alternating sides, as fast as he could.

Swimming/water work. Walker didn’t have a pool growing up, but after college he became a big believer in the benefits of exercising in the water. He didn’t do traditional strokes but made up his own exercises like the underwater “power claps” and a modified breaststroke, in which he thrusted his body upwards and out of the water each time he moved his arms back. He also did his taekwondo kicks and punches underwater.

Speed was never the goal with these pool exercises, but rather maximum resistance. “Just get in the water with the idea in mind to fool around with a stroke or an exercise until you find the best way to do it and the best way to hold your hands to get the most drag in the water.”

Other Exercises

- Monkey bars — would traverse back and forth on an “exercise ladder,” experimenting with going fast and slow — sometimes swinging his body a lot, and sometimes trying to keep it as still as possible (here are some more ways to use playground equipment to get fit)

- Squat thrusts

- Rope climbing

- Stretching

- Jumping drills/plyometrics — jumping over a box, side-to-side and back and forth, to increase agility (here’s how to build your own plyo box)

- Jumping rope

- Dips — up to a 1,000 a day

- Squats — up to a 1,000 a day

- Lunges — up to a 1,000 a day

While the Walker Workout certainly isn’t for everyone, there’s a lot you can learn from Herschel’s whole approach to fitness. I hope it’s encouraged you to put aside your excuses, experiment, and become more versatile, autonomous, consistent, and innovative — a fitness renaissance man!

Tags: Exercises