Editor’s note: The following selection on “Poise That Makes One Master of Situations” comes from The Technique of Building Personal Leadership (1944) by Donald A. Laird. It has been condensed from the original chapter.

Can you take a reprimand without blowing up? Can you take a turndown without being visibly discouraged? Can you laugh with the others when the joke is on you? Can you keep your spirits up when things go wrong? Can you speak in public without being noticeably ill at ease? Can you keep cool in emergencies?

The natural leader answers all these with a confident yes.

It is poise that makes one master of such situations. The natural leader is often a person who has deliberately acquired this poise.

No one expects all high-school seniors to have perfect poise, especially when they are sitting self-consciously, in brand-new clothes, before their proud parents and friends, waiting to receive their diplomas.

But they should have some poise. I was recently astounded to see such a group completely lacking in poise. As I look back to that evening, I regret I did not talk to them about poise, for they surely needed that more than the graduation message I gave them.

And the adults! They were worse than the youngsters. The principal was a cuff shooter. His cuffs were all right, but every few minutes he would adjust first one, then the other. He played with his sleeves so much I expected to see him pull a rabbit out of them.

The matronly member of the school board may merely have been laced up too tightly, but she acted like a confirmed girdle adjuster.

The treasurer of the school board was a ceiling looker. He sneaked a look at the audience now and then, but apparently he didn’t have the courage to face them so he kept studying the ceiling.

The minister who delivered the invocation was a pulpit patter. He draped his long hands over the front edge of the pulpit and emphasized his words by patting it. His hands were perspiring, the varnish was sticky, and most of his pats smacked noisily, like a cow pulling her foot out of the mud.

One of the seniors, an attractive lad with freckles, was a nose rubber. He rubbed it with the back of his left hand, incessantly. His nose turned up a bit, and I wondered if he had rubbed it into a tilt.

Another boy kept scratching one spot on his head. Another was an ear puller. The prettiest girl in the front row was a handkerchief tugger. She kept rolling her handkerchief into a rope and then having a one-person tug of war. A blonde with a tantalizing smile was a foot tapper. Perhaps she was a jitterbug at heart. She sounded like a one-person telegraph set.

The two really poised people were the plump girl and the gangling president of the school board.

The pudgy girl was astonished to hear that she had won the D.A.R. prize, but she came forward to receive it with amazing grace. She was perfectly poised and beamed a winsome smile as she was given a crisp new ten-dollar bill. (The boy who won the science prize was so unpoised that he tripped over his own feet when he returned to his seat.)

The president of the school board was a self-made man. Even his clothes looked self-made. He was one of the tallest and thinnest men I have ever seen. He was an onion broker. His language was awkward. He may have known his onions, but he was not well acquainted with the English grammar. But during the few minutes he spoke all these peculiarities seemed to disappear. He was at ease, calm, graceful in his gaunt way, well poised. He had the least schooling of anyone on that platform — and the most poise!

Lack of poise is due to negligence, neglect of simple little habits. Here is what happened to one man who was giving himself the wrong start. He was beginning to fidget so much that people were uncomfortable in his presence. He was getting so ill at ease that he was justly worrying about himself and his future.

He was a brilliant young attorney, handicapped by a lack of poise. When things became difficult or when it looked as if a decision might go against him, he lost all poise.

Opposition lawyers had been quick to notice this, and capitalized on it. They made a point of annoying him until his nervous fidgeting turned into a complete loss of control.

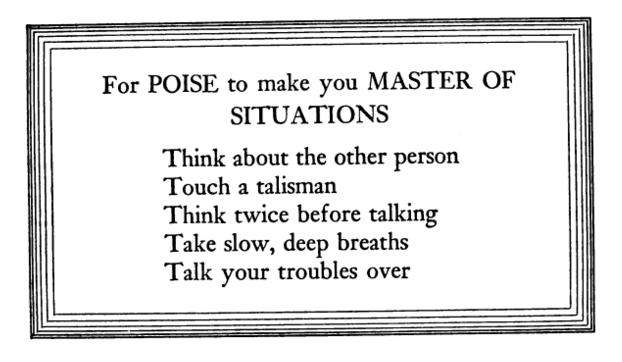

He seemed destined for only a mediocre career, but he was wise enough to realize that he should do some thing to improve his poise. The five things he did for himself are easily remembered: each begins with the letter T.

1. Think About the Other Person

Those sweet young graduates were thinking about themselves. The attorney was thinking too much about what winning a case meant to him, instead of what the opposition attorneys were scheming.

We gain poise when we become less conscious of ourselves and more interested in others.

Our young attorney, for instance, pretended an interest in others at court by counting the wrinkles on another attorney’s face during dull hearings. Previously he had tapped the table nervously, but, by thinking about another person, he remained more composed.

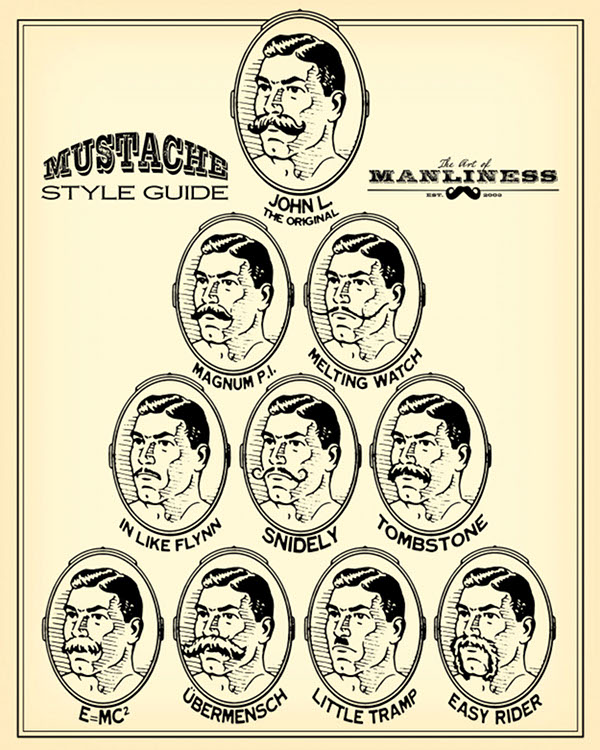

He looked at the neckties the jurymen were wearing, and each juror was flattered to see the attorney looking intently at him. Formerly he had had the practice of tugging away at his own necktie until the knot was finger-stained.

Thinking about others, even in these petty ways, helped him to forget himself, to be more poised, and to put his brilliant brain to work without the handicap of self-conscious fidgeting.

The natural leader has power over others because they can sense that he is thinking about them.

It is not because I am a Scotsman living in penny-pinching New England that I make the following suggestion. It is based on sound psychology.

When you are in a restaurant with someone, do you occasionally have a struggle over being allowed to pay the check? Don’t struggle. Accede to the other person’s wishes. Express your appreciation for his kindness, and drop the matter. Both of you will likely lose poise if there is a struggle for the chance to do the favor. Follow the same practice when offering to carry a parcel for another. If the answer is “No,” accept that as final and talk about something else in which your companion is interested.

Those much despised yes men get farther than they would otherwise because they have the knack of thinking about the other person.

2. Touch a Talisman

The publisher of one of our foremost newspapers was recently hauled before a government board. He knew the attorneys were out to get him and would do everything possible to make him blow up on the witness stand.

He was determined to keep his poise under the severe grilling he would receive, so he used a talisman. He is not a superstitious person and has no belief in magical charms, but he knew this talisman would help him keep poised.

The talisman was nothing more than a small piece of paper. On it he had written: “Keep cool. Don’t be smart. Smile.”

He carried this in his side coat pocket. While on the witness stand he kept his hand in this pocket, fingering the talisman that reminded him to keep poised.

When he was on the verge of snapping back with a smart answer, the paper reminded him not to be foolish. It kept him smiling, much to the irritation of those who cross-examined him viciously, trying to get him mixed up.

This talisman kept him calm, and his calmness so exasperated his opposition that they were the ones who blew up.

A secret prop of this sort helps give confidence. It takes the place of a trusted adviser to whisper encouragement and sensible advice. The secret prop our young attorney selected was a photostat of a complimentary note that had been sent to him by a prominent attorney. He had the copy mounted between two transparent sheets and carried it in his pocket. He seldom looked at it — the friendly feel was reminder enough.

Young Sam Houston was a lively, high-spirited lad, who caused his widowed mother more trouble than her other eight children combined. Sam had just turned twenty when he was aroused by the War of 1812. When a recruiting demonstration took place in his small Tennessee town, Sam stepped up and took a silver dollar from the drumhead. He was in the regular army by that token, but, since he was under age, he needed permission from his mother.

She handed him a gun, saying, “My son, take this musket and never disgrace it: for remember, I had rather all my sons should fill one grave than that one of them should turn his back to save his life.”

Then she slipped a plain gold ring on his finger. Inside this ring was engraved a single word. That ring was his talisman for fifty years. The one word in contact with his flesh guided him through a lifetime of danger and leadership where others faltered.

It brought him back to little Maryville, in a year, wounded, the outstanding local hero of the war.

As a result of that talisman President Andrew Jackson esteemed Sam above all other men he knew.

It caused Houston to resign as Governor of Tennessee rather than say a word to besmirch a woman’s reputation.

It led to conduct which gave Sam Houston, above all others, the confidence of the Indian tribes of the South and Southwest.

That talisman gave him force to lead a wavering mongrel army to defeat a trained army twice its size and liberate Texas. Twice he was president of the Republic of Texas. He, more than any other, brought Texas into the Union at last.

It was not until his death that any man knew the command of that talisman he had used for half a century. Then his wife slipped the ring from his lifeless finger and held it to the light so that his children, too, could see the word that had led Samuel Houston steadfastly through trials to victories.

The word was “Honor.”

3. Think Twice Before Talking

The poised person has often done his thinking a day, or a week, before he talks. He has planned for possible emergencies and what to do in them. When the emergency strikes, he remains poised because he has prepared for it.

A good word can be said for the “canned” sales talk on this score. The salesman who uses this is prepared to say the best thing when an objection or unusual situation arises, without losing his self-composure.

When folk are angry, flustered, or lose their poise, they let their tongues run away with their heads. Under strain, they may say things they regret later, or they may merely become incoherent.

The cure? Talk deliberately. Think twice before speaking when under strain. The person who talks deliberately thinks ahead of his words. His mind keeps a phrase or two ahead of his tongue and lips.

The brain should be used before the tongue. Collect your thoughts — the right thoughts — before speaking. Pause while talking, if necessary, to collect more. (And don’t stall in the pauses by growling “er-r-r” or “well-I-I.”)

The thoughtful talker seldom lacks poise. It is the old admonition to think twice before speaking.

4. Take Slow, Deep Breaths

When people lose poise they breathe quickly. Their breaths are shallow. This does not mean that people lose poise because they have run out of wind, however.

It does mean that deliberately watching breathing, when in a tight situation, will help to keep poise. An amusing application of this was told me by a man who had three times asked the boss for a raise. Each time he had run out of breath and been scarcely able to talk. The fourth time he forced himself to take slow, deep breaths and, for once, was in control of himself and the situation. He got the raise.

It is almost impossible to be flustered when we deliberately breathe slowly and deeply. The young attorney mentioned above calls this, jokingly, his air-cooled system of breathing, since it helps him keep as cool as a cucumber.

When your voice begins to rise, poise starts to leave. Take two deep breaths and lower your voice.

Often, in discussion, we imitate the other person, and when his voice begins to rise ours follows up the scale in pursuit. But when the other person’s voice climbs, that is the time, of all times, when we should keep ours in a low, poised register. Many moderate discussions have ended in heated arguments from this inclination for voices to be raised. Let the other fellow talk louder and louder; it is evidence you are winning.

A word should be said about the desirability of having a quiet room for conferences. If the room is noisy voices have to be raised for ordinary conversation, and the situation is dangerous for poise right at the outset.

You salesmen, get in a quiet location with your customers.

You foremen, get the firm to build you a quiet office, where you can talk over grievances, wage adjustments, and other ticklish problems without need for raised voices.

And all of you, when your voice starts to climb, take two deep breaths and haul it into a lower register.

5. Talk Your Troubles Over

There is usually a feeling of uncertainty behind a lack of poise. Concealed worries, troubles, and little anxieties generate this lack of poise.

The first four aids to greater poise help alleviate the symptoms but are not likely to remove the cause.

The cause, that feeling of uncertainty, needs to be removed.

Married people are usually more poised than the unmarried, the separated, or the divorced. Married folk can talk their troubles over with each other, except, unfortunately, the troubles they cause each other. They can get their nondomestic troubles off their chests at home.

This is another reason why marriage should be based upon more than infatuation. It is sound psychological advice not to marry a person, regardless of the attraction, unless there is a lift in one’s spirit after talking some real troubles over with him.

Concealed disappointments, suppressed worries, and restrained tantrums create a backwash that sweeps poise out to sea. When these anxieties are confided in a friend or loved one, the troubles are shared; the burden is made lighter because they are no longer hidden or repressed. The repression causes worse effects than the troubles or disappointments.

This is good medicine for many personality troubles, this talking things over with someone in whom you have confidence. Usually an older, a more experienced, or a better-educated person is the one with whom to talk.

Concealed troubles are the natural enemy of poise.

Some people are able to talk their troubles over with themselves and then dismiss the trouble. A young office worker, for instance, was disappointed because his work did not seem to be appreciated. He was on the verge of complaining to his employer about it, and, in preparation for this ordeal, he wrote out notes, for his own benefit, analyzing his troubles, the bad policies of the company, and his own assets.

It made a long list and surely gave him two thoughts before speaking. He was amazed to find that he felt much better after preparing this argument to confound the boss. If things were as he had outlined in preparing the brief, they would soon work out all right. He went back to his work with renewed zest, added poise.

And when he became president of the American Bank Note Co., Daniel E. Woodhull still followed this trick — he wrote his troubles out for himself.

He called it his safety valve.