Think back to your PE class in high school.

If it was like most, you probably spent 45 minutes playing basketball or maybe had a lecture about the food pyramid or something. It was a blow-off class that you took because 1) it was required or 2) it was an easy A.

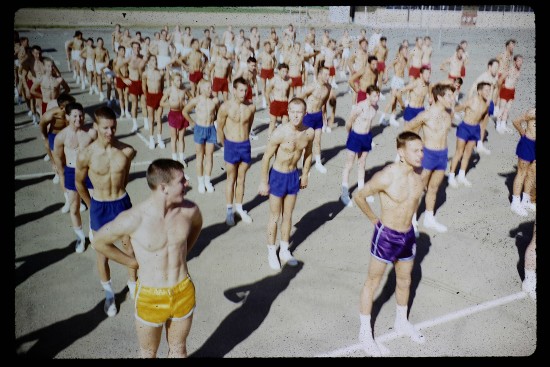

But during the 1960s, high schools across America used a physical education program that was designed to create strong, athletic young people who’d go on to be strong and useful citizens with character.

In short, it was a man-maker.

The program was the brainchild of a WWII vet named Stan LeProtti. His inspiration for it came from the ancient Greeks and 19th century strongmen. The program consisted of a 12-minute bodyweight strength routine and a grueling obstacle course that emphasized functional movement. LeProtti’s system, which he created at La Sierra High School in California, was used in 4,000 high schools across America and inspired John F. Kennedy to make physical fitness a renewed priority in America’s schools. But after 1970, the program faded away and was replaced with what we now know as PE.

My guests today on the podcast, Doug Orchard and Ron Jones, are making a documentary called The Motivation Factor about this forgotten physical education program. Today on the podcast, we discuss the history of the La Sierra program, its effects on the kids who took part in it, the routines they were doing, and the conversation they hope to start about physical education in today’s schools. Before you listen to the podcast, I highly recommend watching the trailer for the movie so you have a visual image of the workouts these kids were doing:

Show Highlights

- How the La Sierra PE program helped a former participant battle cancer in his 70s

- The ancient Greek and 19th century inspiration of the La Sierra program

- The philosophy underlying the La Sierra program

- How physical fitness is a necessary part of civic virtue

- The fitness routine students did in the program

- The performance ranking system that designated fitness levels by short colors (and why it motivated students to push themselves)

- Why John F. Kennedy wanted all high schools to follow the La Sierra PE program

- How programs like La Sierra’s can reduce bullying and increase academic performance

- Why exercising in groups is one of the best things you can do

- Why we need to bring back a program similar to La Sierra’s in today’s schools

- And much more!

Learning about La Sierra has fired me up. I want something like this for my kids. Heck, I want something like this for myself. I’m a big believer in the idea that physical fitness is a vital component of civic virtue. I want more people to know about this program, and the documentary that Doug and Ron are making is the best way to make that happen. This film can spark a much needed conversation about the dismal state of physical education in our schools.

The film is in post-production and Doug and Ron need more money to finish the film up. They’re taking donations for the documentary on Indigogo. If you donate $25, they’ll send you a copy of the strength and endurance routine that the La Sierra students took part in each day. I’ve made my donation. I’d love to see the AoM Community rally behind this to make the documentary a reality.

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Transcript

If you appreciate the full text transcript, please consider donating to AoM. It will help cover the costs of transcription and allow other to enjoy it. Thank you!

Brett McKay: All right, here we go. Doug Orchard, welcome to the show.

Doug Orchard: All right. Thank you very much. I appreciate that.

Brett McKay: You are working with a guy named Ron Jones who we’ve been trying to contact. Haven’t gotten ahold of him yet, on a documentary. I don’t know how you discovered this, how he came across this but as soon as I saw this I got to talk to these guys. It’s a fascinating part of American history. It’s about this fitness program that’s happened across the country , but a particular school during the 1960s and ’70s, a high school called La Sierra. I’m curious. How did you first learn about this fitness program out of this high school in California?

Doug Orchard: Well, I actually three years ago was assigned to do something, I don’t ever do, make an infomercial on some Footlog product. Ron Jones was one of the industry experts out there that asked me as an expert testimonial for this compnay. I met him that way. After we got done there there was a traffic jam even out in the desert in LA area and we had breakfast. He was telling me about how America has de-evolved in physical fitness levels and physical education. That it used to be at a much higher level in the 1800s than we are today. Because of my background, I knew we had done that with education but I honestly with my background, I just assumed that we were hitting higher plateaus, because you see these new levels that we performed in the Olympics and everything. I assumed that was across the board and people just were fit historically because they worked out on the farm.

They just moved more than we do today. I had no idea that they did the gyms and everything else. He said that he had been working and wanted to do a documentary on the history of physical education. I said, nobody’s going to watch that. It took about a year until he told me about La Sierra and when I understood the La Sierra story and that’s part, most people who really look at this, they know about La Sierra, because it was the last great physical education program that made a national impact. Nothing’s been at that level since. At that story it seemed quite interesting. He was still working on getting money and we understood that was coming down the pike.

In the meantime there was one person who was movie, that I found about out of this area and I wanted to go interview because it was a quick easy interview. When I interviewed him and saw firsthand, here’s a guy who’s 70 years old, the impact it made on his life outside of the waistline, it was life changing for me. That’s when we did it without money. We just did the film. so it’s been a cool experience. Maybe I should tell you the story.

Brett McKay: Yeah. Tell us the story.

Doug Orchard: Because it’s not in the film.

Brett McKay: Yes.

Doug Orchard: Here was a guy who from the age of second grade on, his parents worked for the oil industry and he would bounce around every two months they had moved. They’d move, I mean it’s not little moves. They’d move from California to Texas and Texas to Colorado and all over the place. As a result every two months he’s moving and some states would say he’s a second grader, other states say he’s a first grader and he had that problem. Significant social problems, significant everything. Not an achiever. For some reason they just stopped his freshman year he finds himself at La Sierra High. He had been in fights all the time. He says he was about ready to drop out of school. He was going to be one of the statistics that we see.

The program and the level of achievement that was there, the structure was so effective for him, that it transferred to the other areas of his classes. He started believing in himself and all that. He went on and became this really decorated individual, military and what not. He did a lot of great things for our country. He had a normal productive life. When he was about 65, he had a very simple basal cell skin cancer in his ear, that had to be removed. They used a Mohs procedure. In that process infection got into the blood stream, went down to his bowels, infected everything. They had to go in and take everything out.

From that moment on he was on oxygen. He has a bag he has to carry. Then he goes into heart failure. It was six months of rehabilitation before he could walk. He tells me that when he got to the length of the first house. It took him six months to be able to walk the distance with a walker, one house length. He says, he looked at the door and he had a flash back of back in the day when he was at La Sierra High PE, doing ten pull ups for the first time, and how Coach Stan LaProtti had ran up to him, congratulated him and said that’s tremendous. That was the word he always used. He says, but let me tell you, if you can do 10, I bet you can do 11. There’s always one more.

He thought about that, when he looked at that door and he says, if I can do one, I can go two house lengths. By the time I met him at 70, he didn’t have a walker. He still has the oxygen and the bag he has to carry for the rest of his life. His attitude, he says that every challenge he’s faced throughout his life he would think back to the days when he was on the field doing this PE program. That’s what he leaned on to overcome the stuff that life threw it. I started thinking about what is our problem in America right now? We incarcerate more human-beings. 25% of all the human-beings that are incarcerated in the world are incarcerated here in America.

That’s 4.4% of the world’s population. We have a lot of big issues. I was fascinated to see how physical education played such a significant role to overcome all of those. That is what I did not understand. I think most of Americans right now don’t get.

Doug Orchard: Ron Jones Jones is available now, by the way.

Brett McKay: Okay, well we’ll bring in Ron right now.

Ron Jones: Ron here.

Brett McKay: Hey Ron, this is Brett McKay. All right, the gang’s all here.

Doug Orchard: Great.

Brett McKay: Well hey Ron, we just finished talking about how Doug discovered this story. How you met. I was about to get into sort of the history of La Sierra program. Perfect timing.

That’s an amazing story about the gentleman who was able to use his experience in the PE program to battle cancer and overcome that obstacle in his life. I’m curious, what was the origin of the physical education program at La Sierra. We’ll get into the details, like what was involved. It was really intense. Why did this coach decide to start this super intense physical education program at his high school?

Ron Jones: It always goes back to who taught you. He had some good mentors along the way. He also came out of the World War II generation, which a lot of these guys still had those classical methods that really originated with Colonel Herman Koehler in World War I at West Point. When we lost site of the World War II generation we started losing those historical methods. They had brought back the World War I methods for World War II and LaProtti was part of that generation that basically unlocked at least part of that movement code again. A lot of the guys came out out of World War II. They went to college on the GI Bill and they ended up coaching and teaching PE. LaProtti was one of those people.

Brett McKay: In the trailer that you guys made for IndieGoGo or Kickstarter. You talked about JFK, sort of having his hand in this revival of physical culture in America. Why was JFK so concerned about physical fitness in the nation’s youth?

Ron Jones: Well, he was raised in the Boston area, that’s a stronghold for physical culture. On the East Coast we have older cities. That’s where those classical methods would have been very prominent in the late 1800’s, early 1900’s. He came from that background, was an athlete and had some severe back injuries and was actually making a comeback on the physical side, because of working with Dr. Hans Kraus. Bonnie Prudden was Hans Kraus’s research assistant. Bonnie and Coach Stan LaProtti were actually colleagues and friends. It’s funny how all this loops together. JFK, he was a renaissance guy. He had the big picture that we’re trying to explain in the film.

He understood the connection to the Greeks. He understood the connection of the mind and the body, to building better citizens through physical education. Not just the physique part, but learning how to think better and how to be better people. Interestingly though, JFK was inspired by La Sierra. It wasn’t the other way around.

Brett McKay: Interesting.

Ron Jones: I don’t know if everybody understands that, but LaProtti was doing his thing before JFK was involved, and JFK heard about it.

Brett McKay: Fascinating.

Doug Orchard: What’s also interesting here is, there’s a total trail all the way back. We can go straight back to the early 1800’s in Germany and then [inaudible 00:11:34] with renaissance research. Going back to the Romans and then to the Greeks. Stan LaProtti was trained by a group that was probably every bit as good as La Sierra. We just don’t have as much footage and everybody is dead who participated in that program. What’s interesting here is the students are still alive. We have footage. It was such a popular program that they say that they would have in a normal week, there would be three visitors. Visitors from Russia and all over the place would come and just watch. They had these bleachers where people would watch them work out, the students.

It was so well known, so well documented that it’s pretty simple to put something like this together and really address a lot of the things, the prejudices we have of how we think students would have reacted or would react today to this program. We could really go in and interview them and point out, how was it? What was it really like to do this? Was it drudgery, or was it good, and how did it help you? The bottom line is it was classically based. It really was nothing new. It really was just a fragment of how it used to be.

Ron Jones: La Sierra was bringing back the old stuff, just like Muscle Beach. We look at Muscle Beach and we think this was, no they were bringing back the old stuff that their parents used to use. Muscle Beach was not new. They had learned that from their parents who were involved in classical, medical orthopedic gymnastics coming out of the 1800’s. It involved a lot of off the ground training, acrobatics and gymnastics.

Doug Orchard: The other question, he had Ron, the other question he had was what was the impedance for JFK and it goes back to, he was a Senator while Eisenhower was president. That’s when the results of the first tests came out. Go ahead Ron.

Ron Jones: It’s geopolitical. There are spikes of fitness in times of conflict, so this is what history shows us. What was going in the 50’s? The Cuban Missile Crisis. The Soviets were getting into outer space. There were things like this. If you look at this, the Bay of Pigs, that was a very serious time for America and there was a lot of concern we were going back to war. Eisenhower said we lost 20% more troops in World War II than World War I, based on lack of fitness alone. There was a great concern starting around 1954, that Americans weren’t fit enough to preserve our national security. That was tied to the back postural fitness test that Dr. Hans Kraus created in 1940, and Bonnie Prudden was part of that, as I mentioned before.

This whole thing to get fit again basically hinged around the Kraus Weber Test in 1940 that was presented to President Eisenhower. In 1954, Bonnie Prudden was the person that put the test in his hand and explained it to him. It was out of that that the President was so concerned, he formed the Presidents Fitness Council. That was the origins of the Fitness Council. Then we had the sport explosion. When you look around today and you see all the sports stadiums, we really didn’t really have that prior to the Kraus Weber test being presented to the President in 1954. We exploded into sports thinking that that would fix it, but we knew in 1920, or prior that sports was part of the problem, not part of the solution, because all sports created asymmetries and imbalances in the body.

We’re still not learning from history. What they knew classically is you had to prepare your body to do the sports, instead of just doing the sports to get fit. It just doesn’t work that way, and we’ve been beating our heads against the wall for a long time. The people that figure this out, they start moving differently and they start moving better. They increase their physical literacy. They decrease their injuries. They increase the cognitive ability of their brain to control their body and things start rocking. We want to be able to give that to people in the film, because there’s more to PE, than just PE and throwing the ball out. That is not classical physical education. It was actually very sophisticated and quite deep and productive.

Brett McKay: Right. Let’s get into specifics. You mentioned that it’s classically based, so we’re talking ancient Greeks. 19th Century physical culture, inspiration from there. Curiously, what was the fitness routine? I guess it was primarily boys that took part. I’m sure girls did it too, but I’m sure it was primarily boys. What was the typical fitness routine that these students took part in?

Doug Orchard: This is kind of interesting too, because when you get into La Sierra, it looks like they did that off the ground training. Side, straddle, hop jumping all period long and that was not true. They did the calisthenics the first 12 minutes. Then for the main part of the PE period they had a classical PE program which involved restorative arts, to restore the body to its natural state. Their strength, endurance, exercise routine actually was restorative or corrective in nature, as we’ve explained in the training videos. They also had a martial arts component that was a second content area of classical PE. The first was restorative arts. The second was martial or self-dense, or national defense.

The third was pedagogy, interval sports, recreation, played games, dance, things like that. They were doing the restorative correct work. They actually had some martial arts. They had some judo involved in their program. Then they would play some sports. They would do games and things like that during the main course of the period, unless they were testing or something of that nature. They had all three components at La Sierra. It wasn’t like they just did jumping jacks all period. A lot of people don’t understand that. It was a classically based program meaning hey had all the three content areas represented, and also taught very well.

That’s another thing, the teachers really worked hard there. You can’t run a program like that throwing the ball out. You have to be actively engaged and be a very dedicated educator.

Brett McKay: One thing that made this program unique, I thought was really fascinating. There was like a ranking system that the boys, could go through.

Doug Orchard: Yeah.

Brett McKay: They wore different colored shorts based on their rank. What was the purpose of that ranking system, and how did they advance from rank to rank.

Ron Jones: It was called ability grouping, that’s the technical term. It was adopted by about 4000 schools, so my high school in Central California, actually used a version of La Sierra. It was pretty watered down, but we had four different colors of shorts. Just like if you went into a math class, you wouldn’t go into advanced trigonometry or advanced algebra. You have to work your way up in ability. Physical education, at least parts of physical education started using this type of system as back early as the 1920’s. Again, La Sierra did not create the ability grouping system. It was something that was done before that LaProtti learned from others.

A lot of people look at that today and say, well you know it’d be negative. You’re ostracizing certain kids, because they’re not fit enough. As one of the veteran teachers who taught at La Sierra 26 years said. If you have a bone head math book, you work your butt off to go to the next level. This is what you do. You want to rise one step in the ladder. This is how we’re wired as human-beings. The Greeks called arete, a-r-e-t-e. It means striving for excellence. You’re always reaching, you’re striving for excellence. You’ll never truly be excellent, because you’re human and imperfect, but the idea, the big idea is to strive.

When we lose our philosophy for striving, that’s when we’re dead, we’re done. La Sierra had all of this built in. The philosophy of the program was very important. They had regular meetings at La Sierra, just to talk about the philosophy of physical education. That means they were classically trained. You don’t see that in PE today.

Brett McKay: No.

Ron Jones: How many times does the PE Department of a high school have a philosophy meeting?

Doug Orchard: One thing I interviewed in the film, an individual who was a coach there from ’61 to ’63. Then he left, went on and taught at another school that did not do the traditional PE at the time. Then after two years, he says if he didn’t have a chance to go to another school and start a program from scratch that was more like La Sierra, he was going to just quit, because he had seen it both ways. He saw the kids, their reactions. He was able to replicate La Sierra down in Bakersfield at a school and had great success there. What he said that he noticed. They always did the test. The Presidential Fitness Council, they had a fitness test for many, many years. Pull ups are one of them. You go up there and the kids would have to do pull ups.

After a few it kind of hurts. They would just stop. They had a couple more in them at least, but there was no real incentive for them to keep striving. He said that the kids in a traditional program typically never achieved the fitness levels that they were capable of, and experience what they would need for the rest of their lives to maintain that. They didn’t have a real reason too, they just went in and took a test. Not too dissimilar to what’s going on with our current testing in academics right now and different things, where they’re just teaching kids for a test, rather than teaching them to learn, the joy of learning.

He says, that that color system, he ended up going on later and got his PhD and wrote his dissertation just on that color system tested. Kids who were in a traditional PE program versus kids that were in one of these kinds of programs. He tested the lower third of both schools. The theory was that those who were in a La Sierra kind of a program would have a lower self-esteem, because they were stuck in those light shorts. They were the beginning level, never got out of it and somehow they would feel that in some way. Then what he found was that those kids at that performance level. That was based on the national test scores that were going on at the time. How many pull ups and what not, Presidents Fitness thing. They took the lower in both schools tested and there was no difference at all.

What was different was the physical level. The average low level could do about 9 pull ups, at the La Sierra School. The average low, the other school would be 2. Otherwise, it was the same. It didn’t do anything to make a person feel better or worse. Instead it was the motivation factor. That’s actually going to be the title of the film, Motivation Factor, that really provided a reason why they should keep trying, that there was something for them to accomplish, another thing for them to achieve for those who felt motivated by it. I’ve also interviewed people who could not get out of that, both today, 50 years later, as well as kids currently in the system right now in schools that are still doing this.

It was really interesting to talk to them. They were very positive about it. All the thoughts that we have to inject into it, that somehow it’s negative, it’s just not there. There’s no scientific evidence on the peer reviewed study that demonstrated it.

Brett McKay: That’s interesting.

Ron Jones: Yeah, that high school is actually West High School in Bakersfield. They went on to beat La Sierra at a National Marine Corps Fitness Championship. He was the guy that wrote the PhD study, Dr. Tucker was mentored by Stan LaProtti, so it’s kind of an interesting story, if you start unraveling everything.

Doug Orchard: Yeah, the other thing that’s interesting with him is really the story. What it took to get a school to do this in the first place. Then he went on and became a principal and eventually a superintendent. He said that as a principal and superintendent he was never able to get a decent PE program up and running, because he didn’t have the coaches there. They just didn’t have the background or the interest to do what was actually much harder to implement and much more time intensive and what not. Then we’ve seen plenty of coaches stuck where they don’t get the support from the parent level or the administrative level, when in reality you need all of that. You need the parents there. You need the coach there. You need the principal there, superintendent, you need all of it. That’s what . . .

Ron Jones: Here’s what disturbing and also drives us passionately to help inspire people through the film and the work, is that this is the kind of fitness that builds civilizations. It’s the kind of fitness when you don’t have it that destroys a civilization or a society. We are at the tipping point. We aren’t at a level of health and fitness that’s sustainable. We really need to take some action. We don’t have to recreate the wheel, it’s already been done and it’s been done very well. We just need to unravel the history enough, so we can start again without having to drive while blind. We don’t need to do that. Thousands of years of human evolution and movement, they kind of have it figured out. Yeah. There’s some basic things we need to be doing that we’re not.

Brett McKay: Right, I think I read that Look Magazine article about La Sierra. I think it was on one of their websites. Well, it was interesting some levels they were doing, meeting or surpassing the requirements for the Navy. They were stil 14, 15-year-old kids

Ron Jones: Yeah, they blew away some of the military academy requirements. They were motivated. LaProtti wrote about motivation on philosophy. While we look at it and we look at the very physicality of La Sierra with the 8 pack abs and all the different configurations of off the ground apparatus. If you really get behind the scenes, it was mental. It was philosophy and it was mental stability. It was much, much deeper beyond the physical alone.

Doug Orchard: What Ron is bringing up is something that in looking at this thought, how do we do this today? We all in some way kind of see that it would be a good thing for us to be healthier as a people right? We understand the medical problems. 80% of our healthcare costs are preventable and all that. What are the other reasons we should be fit? Are there other reasons besides the waistline and health. That’s where we really focused for quite a while. I interviewed probably 40 different PhD’s and MD’s, the top surgeons, the top researchers in the world. People like John Ratey, there at Harvard Medical School, who wrote that book Spark, exercising the human brain in relationship.

A bunch of neurosurgeons, Michael Roizen, he’s the Chief Wellness Officer at the Cleveland Clinic, just a whole plethora of folks. What was interesting to me was how far our science today has come in proving the correlation between high cognitive, as well as mental stability with exercise. In fact there does not seem to be a way to achieve our brain’s potential without it. It is how we become smarter and how we become mentally stable is through exercise.

Ron Jones: Again, it goes back to the Greeks. It goes back to the Greeks healthy, mind healthy bodies. Sound mind, sound body.

Doug Orchard: That’s just it. That’s just it. When we look at history that is a big component as to why in the 1800’s it was recommended that we spend a third of our time doing physical education and why the Greeks were spending half their time on physical education. It turns it wasn’t this over infatuation about how their bodies looked. It was productivity. It was to be smart. It was mental stability, as well as and this is the part we really, obviously I didn’t understand for some time and was shocked to see is your social. Your sense of community. That is taught through group physical activity, together.

That’s how its been done in the past. It’s how nations are built that Ron explained. In a lot of ways that’s what’s missing. We know that we have an apathy problem in our country today, in America. This is actually a global issue. It’s correlated to a person’s physical movement level. Where are we at? The less you move, the less you feel like doing. It’s really that simple, but they’ve proven that now. Here we have science saying it. We have history saying it and yet we’re really not listening. Ultimately in doing this film I realized that we really don’t listen to science and we really don’t listen to history. Who are we listening too?

Ron Jones: The point I want to underscore here is, before people just go out and go crazy and just start doing more. The history lesson is very clear. We need to move better first, before we move more at random. I want to point that out. I’m going to cite Colonel Herman Koehler back at West Point in World War I. He was adament about safety, quality. He talked about the neurological quality of movement. He was very assertive about directing the instructors to never train into fatigue with the men, and to preserve that economy of movement. The resiliency. Especially in World War I where people were moving more physically, instead of in vehicles. You have to move well for a long time on limited rations.

You couldn’t afford for people to get hurt. If you want to know how people moved really well with limited equipment and support, you have to go back pre-1920. Look at somebody like Herman Koehler. That was a game changer for me as I got more into this, I realized no, it’s not just that the movements were different, and sometimes harder, it was the intelligence. It was the physical literacy. That’s the big picture. We’ve got to move better. We have to have educated professionals that can teach that. We can remake the equipment. We have the catalogs. We have the pictures. The reason that it took so long to unravel La Sierra, we had to figure out the teaching methods.

That’s what we were after. People keep asking me all the time, what were the upper marks for the testing for the advanced levels? I go, that’s not what you want. What you want is how they taught it. How you taught a side, straddle, hop. How do you teach a push up to World War II standards? Most people don’t know. It’s completely different than most people do a push up today. I’ve had many strong men doing sets of 20, and when they do a World War II vintage push up, they’re down to one or two. That’s when you start really learning about your body and getting stronger. You stop getting hurt so much.

We don’t have any records of an official injury, any kind of injury problem at La Sierra. We’ve talked to all these people. The coach that was there 26 years says injuries were a non-issue. When you look at what’s happening today with injuries and people are walking and getting hurt, then you look at something like that, is was so vigorous. Yet, they’re not hurting people. Okay, something’s going on here. We need to start investigating this intellectually, and take a rational look at it. That’s why it took so long, but it’s well worth the effort.

Brett McKay: Right. You mentioned a while back that the coaches would get together and talk philosophy. What did they discuss in these philosophical meetings? Was it philosophy underlying the fitness, or were they trying to figure out how to convey a bigger message to the students through physical fitness. What was going on in those meetings where they discussed philosophy?

Doug Orchard: Hey Ron. Why don’t you think about. Let me think on that one, while you think about that response.

Ron Jones: Okay.

Doug Orchard: Because, one of the people I interviewed he talked about Coach Stan LaProtti was sitting there with a news person right next to him. A kid was complaining about the agility drill. This is a really high octane thing you do at the end of the strength and endurance routine. He goes, oh I hate these. I hate this part. He said it out loud. The coach leaned over to the news reporter and said, now you watch. That kid has a problem in math. In two weeks his math score is going to go up, because of what we’re going to do right now. One, the coach knew which kids were having problems in academics. Second they understood what they were prescribing by way of exercise was going to help them with those academics.

We can prove that now in math with MRI’s of your brain, on what that actually does to your brain, so that you are going to be able to perform better. He understood that. That was part of it. The other part was motivation. It was how do we motivate these kids? There’s a good way to do it and a wrong way to do it, when you have to get in someone’s face and motivate them. Overall this was an extremely positive program. It may not look like it, when you’re looking at the footage, but I have not found one example. I’ve interviewed hundreds and hundreds of these people where it wasn’t just positive for them.

They loved it. They said it was fun. That’s the word that they always used. It was fun when you’re out there as a group. It’s like a big dance. Everyone moving together in perfect unison. They just talked about how fun it was.

Ron Jones: You know I presented this in universities and worked with some younger people the last few years, since getting involved with the film project. It was interesting when I showed them some of the back story of history in La Sierra, the feedback with quite a few of them, was almost a resentment and frustration at least, that they weren’t given the same opportunity to learn these methods. Because, they realized as younger people, they really missed out. It was something really special that happened before them and they didn’t get a chance to do it.

Brett McKay: That’s interesting.

Ron Jones: It’s just interesting to me. In terms of the deeper philosophy, what they were teaching at La Sierra, and again this goes back to the Greeks, because one of the things that they talked about in Greek culture was learning through physical education. About being a good citizen, about thinking clearly, about being a leader. The philosophy of La Sierra, if you boil it down to a bumper sticker, they were teaching the students how to live their lives through physical achievement, physical fitness. They were learning job skills, communication skills, social skills. They were learning how to pay attention to detail. All the things that you need to be successful in life. Many of the alumni said, yeah we learned it there in high school. We learned it in PE.

Brett McKay: Yeah.

Ron Jones: Most people today, if you ask them, what do you think of PE? They have such a negative connotation, because they never went through a real quality physical education program. That’s what it’s supposed to be. That’s what it can be again. It can be done. We just have to get started and we have to be intelligent about it, so that’s what we hope to do with the film.

Brett McKay: Yeah, it sounds like LaProtti had this idea that physical education was there to supplement their learning in the classroom. Now there’s just a big disconnect. PE is just something you do as an elective to pass an hour, so you don’t have to take another harder class. There’s a disconnect there completely.

Doug Orchard: Here’s a big idea. PE was there to create the learning environment in the class room, how about that one? Because, without it, you won’t have the good learning going on in the classroom, hence today. We’re drilling, we’re killing, our test scores suck. We’re not moving. You know my son right now. He’s getting a pup. He’s learning how to be a pet owner and to train him. He just went through a training thing. He runs upstairs to me yesterday. He says, “Dad, when we get this puppy we’re going to have to exercise it.” You’ve got to exercise it this much, this much, you have to always be running. You have to do this stuff, because if it’s just bundled up with energy, it affects its ability to learn, when you try to train it. You have to have gone through some exercise before you train it.

I thought about everything we’d been doing with this film and thought wow probably the best analogy. Our goal, we don’t need to run around, are sitting there and expecting little kids and young adults to just sit there and be capable to learn. Everybody knows a dog can’t do that. People can’t do it either. There’s a point of diminishing returns. One it’s getting the brain ready. Now one thing that is interesting, Dr. Ratey cited by instituting a 30 minute PE program at an inner city school in Charleston, South Carolina in the morning, they were able to see an 87% drop in discipline problems one semester to the next. 87% drop and then they went and did that in other schools, and it’s that same number. You pretty much have discipline go away. You have a ready interested person, ready to learn, capable to learn. Mentally balanced, restored chemically, ready your brain. You can learn. You’re ready to go.

Ultimately we will never achieve the test scores that we’re trying to achieve both here in America, as well as the whole world problem. They’re all doing the same thing.

Brett McKay: Right and that . . .

Ron Jones: Go ahead.

Brett McKay: I would say that the irony is, that we’re getting rid of recess and physical education so we can spend more time in the classroom studying for this test, so we can do better at the test, but it sounds like that’s actually counterproductive, extremely counterproductive.

Doug Orchard: Well yeah. It’s still proving out.

Ron Jones: Now there are some recent reports of schools increasing recess and guess what? The kids are getting better. Yeah, it’s just interesting. We just can’t keep doing this. Going down this road. It’s not going to work. By the way La Sierra didn’t have a bullying problem. You think of it, man these kids are very physical. They’re probably fighting and pushing each other around, not. That is not the case. It was all for one, one for all. It was a team supportive environment. Everybody pulling for each other. Mentoring, teaching, this is what it’s supposed to be.

Doug Orchard: Yeah, can we hone in on what Ron just said. This idea of all for one and one for all. We’re not … but we found a school still doing this. That started and it’s kind of the end of our film. It’s the big, big secret right? It’s a big deal. I went and it’s an inner city school. You’ve got the whole gamut there. I’ve interviewed kids that live at the country clubs and kids who are homeless right now. They all treat each other equally. I interviewed 60 of them. I was just fascinated in that process. What I saw was, because they’re a team and everybody participates, it’s not just the jocks. Everybody participates. The objective is to get your whole team to progress together.

When you’re done running. If you’re fast. You turn around and you go track and help the rest of the group and cheer them on, get them in. Because, you’re out there as a group trying to move perfectly together. You’re outside yourself. The whole experience is outside of you. You’re now part of the community. You’re part of a team. They have no bullying. They treat each other like a family. Even though it’s probably the most diverse ethnic and diverse economic group I’ve ever seen at any school. I saw this and it gave me a lot of encouragement. I just thought you know. Then we went and interviewed one of the top historians in the world who looked at this historically in using these classical education things.

That’s where we saw that the whole impedance of physical education historically, the reason the government has wanted to do it was to build nationals. When you get large groups of people to move together, it creates a sense of community independent of the ideology that was used. You see in history Germany doing it. You see in history America doing it. You see in history Hitler doing it. You see right now them doing it in North Korea, Russia and you see ISIS doing it right now. It doesn’t matter what the ideology is. If you want to build a group of people and get them to be one and be a community and actually care about something, besides just themselves, you have to get them to go orchestrate and move together. Get them to dance together, do whatever together, but they’ve got to do it together. They can’t do this alone.

Ron Jones: Let me dissect this a little bit. You talked about what with the philosophy behind La Sierra. A large part of this goes back to what’s called the noble purpose. I don’t care what system you study. It could be the German system, coming out of Yan in the 1800’s or Lang out of Sweden, the Finnish, the Czechs, Americans. They all had some kind of guiding philosophy that was related to a noble purpose. It’s a betterment of mankind in general and helping the whole planet if you look at it that way. There are countries that have a national purpose, but it’s not necessarily noble, so we can argue that North Korea definitely has a national agenda, national purpose. In American culture we would not say generally that that is noble.

The idea, the Sokols are great to look at from Czechoslovakia. They had an amazing, almost like a cradle to grave physical literacy system. You were born into it. You went through it. A lot of people competed in it with rhythmic gymnastics on the field. They could put over 14,000 people on a field at the same time doing beautiful aesthetic high quality movements, with mass calisthenic drills. Just absolutely amazing. Then as you aged you would teach and mentor. It was all volunteer. They would have these huge festivals, they were called Flet, F-l-e-t in Europe. All these people. Hundreds of thousands of people would come in. They would have these things for weeks at a time. Different cities would feed different teams. Everything was volunteer.

They brought that to America. Interestingly in World War II they had a rejection rate from the Czechoslovakian men going into the service, less than 1%.

Brett McKay: Wow, wow.

Ron Jones: That’s how fit they were. Less than 1%. Now, their purpose for doing this was to build better citizenship and to mentor the young and to be healthy and fit. I have a lot of information on the Czech Sokols and they constantly are talking about healthy body, healthy mind, being positive, being productive. It’s all there. It was there very strongly as late as about 1965, which was about the time La Sierra was peaking. It’s not that long ago. That’s why we really want to zero on La Sierra a little bit, because they were the last high school to figure it out at a level that changed the country and influenced the world. There might have been pockets or this or that, but no one school has done it since La Sierra.

Doug Orchard: The other thing that’s interesting when you interview the people today, 50 years later after the Class of ’61 for example. They’ll tell me how somebody got cancer. Suddenly the whole school rallies around. It didn’t matter what year you were. It just quickly goes out that so and so, one of our Longhorns is down and out and people go over. They go and mow their lawn. They’ll help them out financially, whatever. Someone loses their job. It didn’t matter what year it was. It didn’t matter the fact that they didn’t know them at all. They were a sense of community. They were a team. They went out and helped them.

Kind of similarly as if you were in a sports team and you were nationally ranked your group. You kind of kept that relationship together. They did that as an entire school and as a community. It doesn’t mean that everything is all perfect. I’ve found plenty of examples. The other thing I found interesting is when we wanted to do this film, we needed like half a million bucks, consider a low budget film is anything below a million. We figured we’d need at least half a million to try to even get it to the point it’s going into a theater. We got 10,000 alumni easily out of that school. If they all just gave 10 bucks, we’ve got a hundred grand.

Well we had about 40 or 50 of them contribute. We raised in total with everybody 40 million views on Facebook and half a million on YouTube, we raised about $20,000.00. That was hard for Ron and I to sit there. We thought for sure they would step up. Basically I get the sense that it’s kind of like all of us Americans today, all of us benefit from freedom and democracy, except we really didn’t do anything to enjoy this benefit. It’s not because of us, it’s because of the people a long time ago, who gave it to us. Those people knew what they were doing and why. Not everyone really respects that today. I got the same sense from them.

They still retain that sense of strong community, that is distinctly different than those who didn’t participate in that program, is they’re very interesting.

Brett McKay: I’m curious. It sounds like this program influenced over 4000 other high schools they adopted the program.

Doug Orchard: Some version of it, that’s right.

Brett McKay: Some version of it.

Ron Jones: It was global too. Those were 4000 in the United States, but we have records in our archives of Saudi Arabia and all these different countries coming to visit them and communicating with LaProtti.

Brett McKay: Why did the program fade away.

Doug Orchard: That’s a really good question.

Ron Jones: That’s a loaded question, geopolitical again. Do you want to take the lead on that Doug, and I’ll chime in.

Doug Orchard: Well, you know we asked that question. We get different answers. I’m just going to give you all the answers. Because, you’re going to have a tough time really getting it. There were reasons why it faded away after the Golden Era, heading into 1920. The first big wound they got was the Vietnam War. When it lagged on. Because, physical education is really good for an individual, it’s a human body. How do you in an efficient manner get that human body in shape, in 12 minutes, then another 5 minutes of off the ground at the end of the day. Otherwise, the stuff in the middle was just more fun. How do you do that efficiently?

If you’re in the Army, well you do the same stuff. You’re going to do the exact same activities in the Army. They saw the boot camp and it looked pretty dang similar to what they’re doing there in high school. A lot of parents they wanted to oppose Vietnam and the students, felt like they could boycott and protest against PE, then that’s a method to protect against the war. First was the link between what perceived physical education was to military, that hurt them a lot. The same thing happened after World War I, that was really the death knell for a lot of that classical physical education as well.

Then the other part was budget. We saw in the 70’s, we saw in California for example at this high school. One of the coaches said the death knell was when they stopped laundering the towels. They stopped laundering towels. Boys, they’re not interested in taking showers without a towel. They forget their towel to bring it, all that stuff started happening. That was a big factor. The budget was a bit of an issue. The other real factor I think that it really comes down honestly, is when I flushed through all this stuff, it’s the parents. It was the parents support that allowed it to start in the first place.

The way Stan LaProtti got that, is he opened up the school. He even got the moms out and he did these programs with the parents, so that they had a buy in. They saw why it benefited them. It was the next generation of parents who didn’t like little Johnny going out there and have to do something hard. They didn’t understand the why behind it.

Ron Jones: Yeah and then . . .

Doug Orchard: Go ahead.

Ron Jones: The school closed in 1983. Well, the big reason that some of the people fought to keep La Sierra open as opposed to closing one of the other schools in the district, due to some boundary issues, was the fact that the PE program was globally famous, but they ended up closing that and La Sierra is now a community center. Interestingly though, the PE program at La Sierra in the early 80’s was on the way back. They never got rid of it, but it had waned a little bit like Doug said with the war. It was actually making a comeback. We found that kind of interesting and things do cycle. If La Sierra was there today, I’m sure they’d be doing something similar.

Brett McKay: Could we address the female side of this with La Sierra too, because a lot of people bring that up.

Ron Jones: Yeah, Title IX came in in the 70’s we’ve had criticism. Well where are the girls? Well, they weren’t involved with boys PE at the time. We’re historians. We’re recording what happened. We’re not changing history. This is the way it was. You can say it’s good or bad, but in those days that’s the way it went down.

Doug Orchard: Well, what’s interesting with it Ron, the girls had PE.

Ron Jones: They did.

Doug Orchard: They had female coaches and those female coaches at that time, chose not to do this program. They had their own program, which was a more traditional sports based program.

Ron Jones: It was softer. It was softer and more rhythmic. You could say it that way, but I think a bigger issue guys, is that as the World War II generation left the ranks of PE, we started losing the teaching methods. That’s the real issue. I’m going to keep coming back to the teaching methods. Because, when you lose the teachers, then who’s going to do it. I have PE teachers across the country writing me all the time. They know they’re missing something. They weren’t taught in their credentialing programs how to do any of this. They were taught how to do sports. The bigger problem here is that, and people ask me quite often. My son or daughter wants to go do something like you’re doing, where should they go to school? Where should they apply?

I don’t have one single university in America that I can recommend, because we’ve dismantled our quality physical education programs. There are no teacher preparation programs teaching what we’re talking about. They might have a history class and they show some pictures, and they do a little bit of this or a little bit of that, but the richness of American physical education and remember La Sierra was just a brief part of that, has been gone for decades. That’s the bigger program. We have to start educating teachers so we can teach the methods again. That has to be infiltrated into the, we’ve got to get our universities back up to speed.

It’s like when we lost our factories and now we need stuff. We have to rely on another country to do it. Well, our factory for building physical fitness, we dismantled our factory.

Brett McKay: It seems like there is this explosion outside of schools, or like publicly funded institutions, that are kind of doing what La Sierra was. For example, like MoveNat comes to mind. I don’t know if you’ve heard of those guys.

Ron Jones: Sure, yeah, I know them.

Brett McKay: Even like the CrossFit, it seems sort of, not exactly the same. The whole idea that sports should be functional or fitness should be functional. Are these sort of trends in fitness? Is there a way for that to influence physical education programs in public schools? Is there just going to be a lot of push back from that?

Doug Orchard: Will it influence? Yes. I’m going to go back to the big picture. First do no harm. Move well before you move more. It’s always going to be that way in the end. You can fight it. You can deny Newton’s Laws of Motion and physics. You can blow history off, but this is how it’s done. You can’t load people with excessive volume and high intensity if they’re not lining things up. It just doesn’t work. We have to have an intelligent approach to this.

Ron Jones: MoveNat is influenced by the system in French, because Erwan Le Core was from France. He has more of a classical position than a lot of other people out there. That being said, body weight only is only part of it. There are other pieces of apparatus that have to factor into that. You’ll see MoveNat kind of moving more into that now, instead of just working with the body alone. They get the big picture. It’s the mind, body connection, the quality.

Doug Orchard: You are right Brett, in the sense that there is a movement making the old new, where we’re going back. We’re seeing some of these things. We’re seeing higher intensity and different things coming forward. What Ron is pointing out, there is a safety issue. There’s a way to teach this and make it work. What we’re trying to do with the film is show how the why behind it. The purpose of this film, the really why behind it is to be a flag that can be waved to get this to happen again in its entirety, the way it once was. For people to understand it. The reason why we need that today is, because what’s happened in the physical education is really not just dissimilar. I like to use the analogy of what would happen if we stopped teaching mathematics a hundred years ago?

I’m just pitching this for a moment. Where would be at today if 100 years ago, we just stopped teaching mathematics. Maybe we kept the math, so everybody knew what 5 x 5=25. That wouldn’t be much knowledge they’d have to retain. They could do that 20 minutes a day on a Friday, and compete against each other on that. Otherwise, they wouldn’t do math. The problem is, no one would know how to apply it. We wouldn’t have obviously our computers, iPhones, and what not. We wouldn’t even have skyscrapers or bridges being built anymore. If you really think about it, we wouldn’t even have houses, because that still takes math.

We would regress back to pre-Egyptian time period standard of living by stop teaching just that one subject. Well, physical education we stopped teaching it in its entirety over 100 years ago, the real physical education. Today, if you think about the same analogy with math, how would you go back and re-institute it? How would you talk to people about advanced concepts in calculus or algebra even, with when all they know is math X. You couldn’t do it. It’d be really difficult. We are at that point right now with physical education. Our body, the diseases and everything. We are at that point that we need to go back and actually re-introduce this stuff.

There’s a formula that has been done in the past. Societies have found themselves in this spot and how they brought it forward, it’ formulistic in what we need to do.

Ron Jones: Well, here’s an example today. I know a young man who’s preparing for the Olympic trials. The Olympic coaches that he’s working with in strength and conditioning, this guy actually knows some of the historical methods, that he’s worked with I and my partner Shane Hilton. They’re making fun of him, because they say his methods are outdated. Now he’s using the good stuff. He’s using the Indian clubs and the health hormones. He’s using La Sierra. His body is changing and he’s getting better and they’re making fun of him at the Olympic level, because, they say he’s obviously outdated and doesn’t know what he’s doing. He actually knows more than his strength coaches. Right, so this is where we’re at. You don’t know if you don’t know. How do you start the conversation with people.

Doug Orchard: That’s just it. The positive side is the process isn’t that difficult to bring back if you follow the formula. The formula, it starts with a few who understand it. Who dig it up. You’re wrong and all these guys from history who did it. You just have to do the renaissance effort. It goes to the educated elite. That’s going to be our colleges and it’s also going to be our clubs. It’s going to be the different gyms. It’s going to be anybody who has the influence that wants to teach this stuff. Then it goes to phase 3 which is mass mobilization. We’re never going to reach the inner city schools and so many kids who are just finding themselves on a path to go straight to prison. We’re never going to reach them unless we get this back in schools for them. It has to be for every student.

La Sierra actually did combine the male and the female. The last person to graduate from the school, I interviewed her, who got the highest level at La Sierra. An incredible meeting this was for her. It works for all genders, every ethnicity.

Ron Jones: Right, we have young women doing the La Sierra routines now and they’re doing great with it. One of them is over 60 years old. If you have the quality and the philosophy behind the classical methods they will work. You can’t just take the tools and look at the drills in isolation and start just loading them up with volume and forgetting about the quality and physics and the classical teaching methods. It doesn’t work that way, but when you do it the old way, correctly and precisely, things start to happen and fairly quickly. This is why its taken so long to unravel all this, because it’s not just a PE program. There’s so much deep philosophy involved and the quality of movement. It really took some time with a lot of us and deep reflection, going over thousands of pages of information basically, over 100 years ago.

Brett McKay: Doug Orchard, Ron Jones this has been a great discussion. Where can people learn more about the film and the project? Can they still support the film?

Doug Orchard: Yes, they can. Probably the easier link is to go to motivationmovie.com. That’ll take them to the website and all links will go from there. They’ll find a link to go to our Indiegogo crowd funding effort. It’s woefully under funded. I’m about three weeks away from finishing the first real edit cut of this. We’ll go around and start to try to build up some interest and get some support of the film.

Ron Jones: Yeah, we’re . . .

Doug Orchard: Our goal is to take it to theaters.

Ron Jones: Lasierrahighpe.com too, and they can reach me at the leanbraves.com. We also have a Facebook page, that’s got some pretty cool updates on it. I have been popping in a lot of the slides out of the archives and some of the articles and things like that, and making historical commentary on helping to explain the story. Not just the story of La Sierra on the Facebook post, but the story behind La Sierra. What set into training LaProtti to be able to do what he was able to do. LaProtti was an interesting guy, because he left La Sierra and went to be one of the top physical fitness guys in the country with the Presidents Fitness Council. Worked with law enforcement, University of South Carolina. The last part of his career with the military.

He was truly a remarkable professional in physical education and fitness. Anyway, those are good places to visit. I’d be happy to talk to people about it. I’ve worked with the military. I’m working with gymnasiums. Starting to do some workshops. I’ll be in Spain next month teaching La Sierra to some people over in Europe that are interested. It’s moving forward as it should.

Brett McKay: Very cool. Well hey Doug Orchard, Ron Jones thanks for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Doug Orchard: Thank you.