It’s Christmas time once again. In a few short weeks, kids will be joyously running out to the tree to see what Santa has left them…before proceeding to bicker and whine that little Jimmy got more presents than they did.

It’s an issue as old as time, and one that presents itself outside of just the holidays: one of your children feels that you favor his or her sibling more than them. Oftentimes these accusations are simply based on a child’s erroneous or incomplete perceptions, but sometimes a parent genuinely does click with one kid more than another.

Whether or not the favoritism actually exists, parents often feel bad their child has formed such a perception and try to remedy it by taking proactive measures to treat all their kids equally. But according to Alex Jensen, professor at BYU’s College of Family Life, such an approach can end up doing more harm than good. To find out why, I talked with Jensen about why you should aim to treat your kids fairly rather than equally.

The Difference Between Equal and Fair

At first blush, equality and fairness seem like the same thing; they’re both connected to our sense of justice. One can grasp the difference by thinking of 3 children of varying heights trying to watch a baseball game over a fence. Treating them equally might mean giving them each a box to stand on; but the shortest kid still can’t see even while atop a single box, and the tallest child doesn’t need any box to see over the fence. Treating them fairly, then, would mean giving two boxes to the shortest child, one to the middle, and none to the tallest.

To bring the difference between equality and fairness into the real world, Jensen highlights an example he heard from a colleague:

“A friend of hers had two kids and one of them had this disorder which prevented him from going out in the sunlight and he had to be inside all the time.

Despite having this big backyard and lots of space to play, the parents wouldn’t let the sibling, who didn’t have the disorder, go outside to play because they felt like that wouldn’t be fair to the other kid. They were opting for equality. Unfortunately the kid that didn’t have the disorder that prevented him from going outside started to have some physical and psychological troubles because he wasn’t being active in the way a kid should be. His parents are basically having him sit on the couch all day with his brother.”

In this more extreme example, we can see how using equality to keep things “fair” in a family actually resulted in a case of real injustice. But this problem pops up in less extraordinary instances as well. Perhaps all your kids are teenagers. To avoid any conflict about differing curfews, you give them all the same early curfew, even though one child has repeatedly broken your rules, while the other has shown she’s responsible enough to handle a later one. Or maybe one child is able to self-regulate their diet or technology consumption on their own, while another needs more guidelines and monitoring. Being stricter with one child than another may bring howls of “You let him do anything he wants! That’s not fair!” But it is in fact fair, just not equal.

Treating your children fairly requires you to look at each one as an individual with unique needs and circumstances, and give them the specific time, focus, and rules they need in order to flourish. It’s important for your kids to know that what works for a sibling, may not work for him or her.

Managing Perceptions of Favoritism

So you decide to treat your kids fairly, but how do you manage the perception of favoritism that can creep in — especially as they may still be using equality as the measuring stick for proper parenting?

Jensen admits that researchers don’t have much data on this specific question, but his initial hunch is that if you’re really being intentional about meeting the individual needs of each child, accusations of favoritism probably won’t be a problem. Jensen uses an example of a hypothetical family where one son likes basketball and the other likes art. With the son who likes basketball, you’d shoot hoops in the driveway or maybe take him to a game, and with the son who likes art, maybe you paint together and take him to a museum. Tickets to the game may have been more expensive than entry to the museum, so it’s not strictly equal, but it’s fair based on each child’s unique interests and needs.

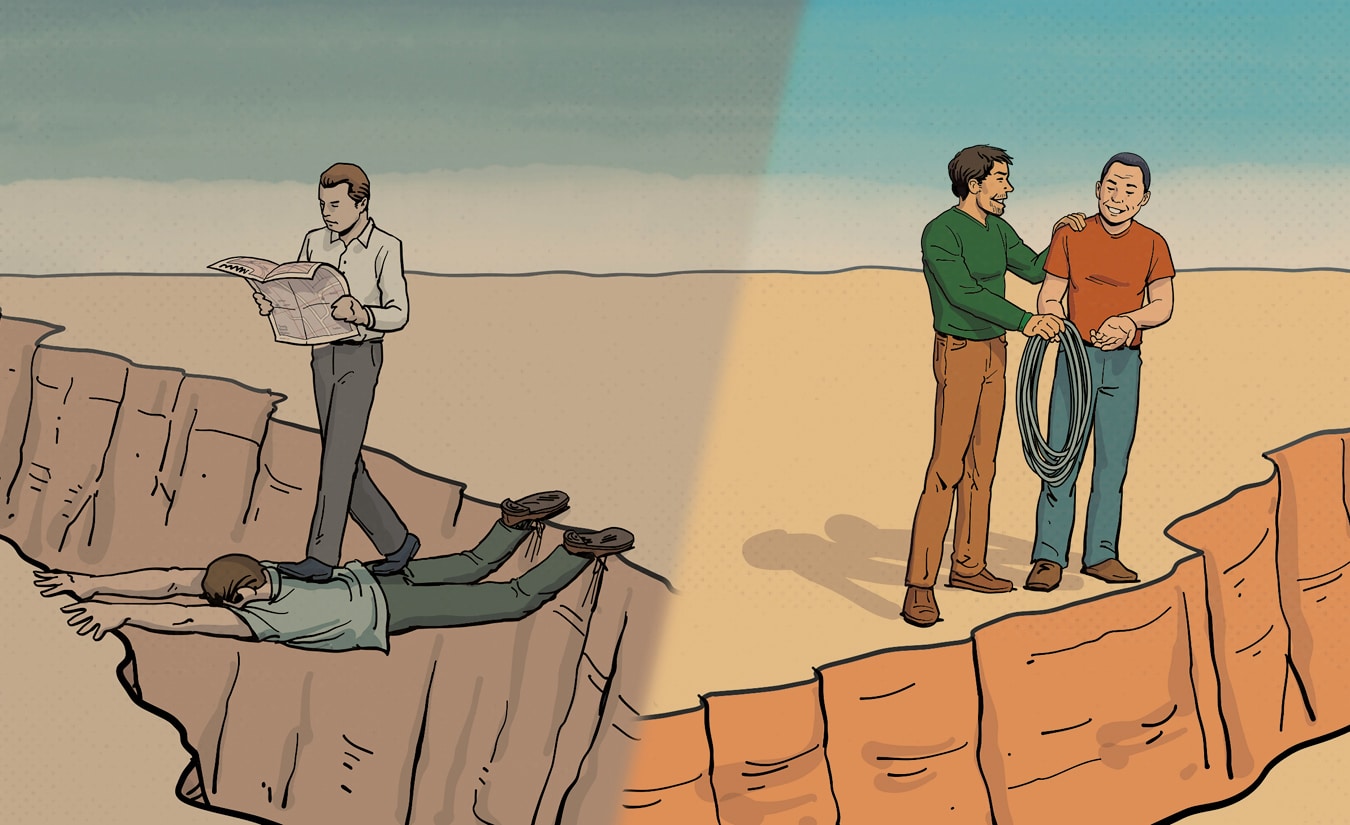

Jensen warns that where you may get into problems is when you invest more time and energy with one child simply because you’re more interested in the stuff he does. Maybe you love basketball too, buy season tickets to your local NBA team, and go to all the games with your one son. But because you’re not really into art, you don’t really do anything with your other son except for saying, “Oh hey, cool drawing,” when he shows you his latest creation.

So while the focus shouldn’t be on strict equality in all things, equality in time and focus does still seem to be an important factor in preventing feelings of favoritism. If you don’t naturally click with one of your kids, you’ll need to be more intentional about spending time and talking with them, rather than hoping these connections will naturally happen.

Even if you do click with all of your kids equally, the things you can and will want to do with them change as they age and move through different seasons in their development. You may naturally find yourself able to do more fun things with your oldest child, who’s mature enough to handle them. A younger sibling may see this as unfair, but you simply have to let them know that their season at that age will come around, and they’ll get to enjoy the same activities as their older sibling when it does.

At the end of the day, you don’t need to overly obsess about how much time and focus you give to each child. While Jensen reports that “Teenagers in unengaged families who see themselves as decidedly less favored are 3.5 times more likely to abuse alcohol, cigarettes, or drugs,” occasional feelings of favoritism can be mitigated by creating an overall family atmosphere of affection and warmth. In other words, children’s worries that a parent may favor them a little less than a sibling are less distressing when they don’t doubt their parents’ love.

So rather than focusing on what you can’t control — your kids’ perceptions of favoritism — focus on what you can: creating a loving and supportive atmosphere in your home.

Fairness and Equality at Christmas Time

So what about those moans and groans that sometimes fill the house on Christmas morning when one child feels like she got the short end of the gift stick?

First, Jensen noted this might not even be a problem in your home. In some families, kids don’t keep tabs on each other’s gifts. Cultivating this kind of lack of competitiveness and possessiveness is something we’ll have to tackle another time. But if it happens to be a problem in your family, Jensen says your approach will depend on the children’s age. When kids are little, their tiny brains still can’t really grasp abstract ideas like costs. So while a four-year-old may have gotten one present that cost $30, she may think her two-year-old sister was treated more favorably with her four $7 toys. So when they’re young, it’s okay to focus more on equality than you will as they get older. Seeing that each kid got the same number of presents is something concrete they can grasp.

As they grow up and their brains begin to understand nuances like price, then you can feel freer to give a varied number of gifts of a similar overall cost. The fact that kids are in different seasons of development means that sometimes certain kids, at certain ages, have more defined interests than others, and thus may get “better” presents than children whose interests are less defined, and who thus receive more generic gifts. Their turn will come (should they discover some hobbies!). Christmas morning may spur some conflict now and again, but it’s also a great opportunity to discuss the difference between fairness and equality with your kids!