During the past few centuries, Christian churches have had some difficulty reaching men. During the late 19th century and even today, churches created special programs in an attempt to get more men in their pews.

But why does this difficulty exist in the first place? And what can be done about it?

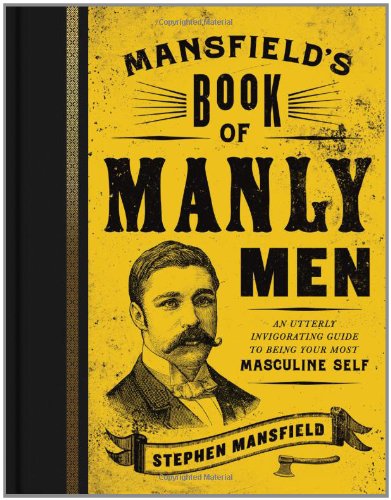

In today’s podcast I talk to author and speaker Stephen Mansfield about this issue as well as his book Mansfield’s Book of Manly Men. If you’re a Christian, you’ll find Stephen’s insights about the church and men interesting; if you’re not a Christian, it’s still interesting to learn more about this aspect of our culture, and you’ll get a lot out of of the second half of our conversation on the virtues and ideals Stephen thinks men should strive for, as well as the great men from history we should study and emulate.

Show Highlights

- Why Christian churches have had such a hard time getting men in the pews

- What churches can do to connect more with men

- The rite of passage into manhood Stephen experienced in Damascus

- Stephen’s Manly Maxims

- What King David meant when he said to his son Solomon, “Show yourself a man.”

- What Winston Churchill can teach us about having a terrible father

- Why men need to re-learn the skill of friendship

- What Teddy Roosevelt can teach us about embracing our wild side

- And much more!

If you’re a Christian man, I think you’ll really enjoy Mansfield’s Book of Manly Men. Unlike a lot of the Christian books out there for men, Stephen’s book isn’t sappy or touchy feely. It reminds me very much of the books for Christian men put out in the 19th century. If you’re not a Christian, I still think the book is worth checking out. Most of the ideals Stephen espouses cut across beliefs. You’re bound to get something out of it.

Listen to the Podcast! (And don’t forget to leave us a review!)

Listen to the episode on a separate page.

Subscribe to the podcast in the media player of your choice.

Special thanks to Keelan O’Hara for editing the podcast!

Transcript

Brett: Hey guys, before we get to the show, one quick favor to ask. If you haven’t done so already, I’d really appreciate it if you would go give us a review on iTunes or Stitcher, whatever it is you use to listen to the podcast. I’d really appreciate your honest feedback. We’re looking for ways to improve the podcast even more. About to invest some more money and resources into new equipment that will hopefully make the podcast … not hopefully, it’s going to make the podcast sound better. I’d really appreciate that. Also by giving a review, it helps get the word out about the podcast. Just want to take this time to say thank you all for your support with the podcast. Really, when I started this back several years ago, I didn’t think it was going to be that big of a deal, but it’s blown up to this big thing and it’s all thanks to you guys and your support in sharing it. Thank you so much for your tweets, your recommendations for guests, books to check out. Really appreciate it. Enough with that let’s get on with the show.

Brett McKay here and welcome to another edition of the Art of Manliness Podcast. A few years ago, I got in the mail this book called Mansfield’s Book of Manly Men. Has a really cool vintage aesthetic to it, looks like something you’d pick up from the 19th century, full of vintage engraving illustrations of Winston Churchill or Teddy Roosevelt and then with these life lessons on how to be a man from these great figures from history. Now he’s the book author. His name is Stephen Mansfield. I brought him on the show to discuss his manly maxims and his ideals of manhood that he espouses in the Mansfield’s Book of Manly Men. Man, that’s a lot of manly there.

Anyways, this book is geared towards Christian men, but I think the ideas and principles that he talks about in there are applicable to men of any faith or lack of faith. On the podcast today, Stephen and I discuss some of the unique questions or challenges of manliness and Christianity and how the two can be congruent and why Christian churches have such a hard time keeping a man’s attention and getting them actually into the pews and what churches can, what they should be doing to remedy that. After that, we start talking about just the manly maxims of Stephen Mansfield and the ideals and what we can learn from great men from history to live a more manful life, so really interesting podcast. I think a lot of great takeaways. You’ll think, you’ll feel a little invigorated and inspired and feel a bit more virile after you’re done listening, so without further ado, Stephen Mansfield and Mansfield’s Book of Manly Men.

All right. Stephen Mansfield, welcome to the show.

Stephen: Thank you very much. Looking forward to it.

Brett: All right. Your book is Mansfield’s Book of Manly Men and it’s a great book. The thing to start off with about, it’s directed primarily towards a Christian audience, though I think a man of any faith or no faith could get something out of it. I think it’s interesting this whole Christian angle because I think this is a great topic of discussion, the intersection of Christianity and masculinity because it’s something that my friends and I discuss quite a bit. It seems that the church has had a hard time reaching and resonating with men. What is it the way that Christianity is portrayed that puts a lot of men off?

Stephen: There’s a natural drift in most Christianity towards the feminine, towards emotional experiences, towards intensely internal things, towards even intellectual things, which doesn’t inherently mean non-manly, but it can in some cultures. If we’re not careful, if we don’t run our churches in a man-friendly way and realize that men are critical to the whole process, then yeah, we can turn churches into very feminine situations. That’s why the stats show that about 70 to 80% of most church attendance is by women.

Brett: Yeah, and this isn’t a new problem either. I think it’s fascinating as I’ve read books from the 19th century about masculinity, most of the books were Christian books. Basically, authors were trying to make the case to men that yes, indeed, Christianity is manly and Christ was a manly figure and we should emulate Him. I think it’s fascinating that this problem that’s been around since 100 years and more is still going on today.

Stephen: There’s no question. I’m sitting in my office in Nashville as we speak and I’m looking across my desk here at a book called Manhood at Harvard. It’s about a movement that happened right around the dawn of the 1900s with men like Theodore Roosevelt involved. It was a great surge of masculinity. It produced a lot of his great works and other leaders out of Harvard and Yale. This is described in a book by Ann Douglas that maybe you’ve read. It’s called The Feminization of American Culture. She’s a Columbia scholar and basically, she says that when the pulpit, when the churches turned liberal and thus turned feminine, and she makes that connection, not me, that it lost manhood. It lost a vision for manhood and then it started losing men from the pews. It’s a fascinating connection that we have to consider, but the bottom line is, you’re absolutely right. When initially, Christianity was seen as a spur to manhood, but by the time we get into the early 1900s, that’s been lost.

Brett: Yeah, the whole muscular Christianity movement, where the YMCA and Billy Sunday, wrestling with the devil. I love that stuff. It’s just a really fascinating parts of our history. Okay, so here’s the question. What can churches do to connect more with men because I’m in Oklahoma. We have a lot of the big megachurches around here, Life Church, Church on the Move. I’ve seen some of the things they’ve done to reach out for men and it’s like have a Harley Davidson night, Super Bowl Sunday, incorporate football into the sermon. For some men, that really resonates, but I’ve had some of my friends who go to these churches where they roll their eyes and they feel patronizing. What can men do or what can churches do to connect more with men?

Stephen: I celebrate anything that churches can do that draw men, so if a Super Bowl does it or the breakfast on Saturday morning, that’s fine. I think I’m with you. I think a lot of that can tend to be like having a soap opera party for women. I think women would not be all that happy about that either. The bottom line is, we need to understand the nature of men. Men are not engaged simply by processing emotions and sitting and contemplating things. They’re engaged by doing. They’ve done a number of studies over the years where they’ll put children, male and female, in a room with chairs and toys and they basically let them do what they want and they observe them. The girls turn the chairs just opposite each other, look at each other, then finally, one of them says, “I like your hair.” Then the guys, though, turn the chairs side-by-side, shoulder-to-shoulder and little boys start looking around and saying things like, “Hey, I bet we could climb up on that cabinet. Hey, I wonder how we can pull her hair? Wonder if we can set that door on fire,” or whatever. How much dynamite does it take to blow up the cat? They start thinking of things to do.

I think this is a key to how men think. Throughout the Old Testament, whenever a man is commanded to teach his son, there’s always a phrase in there like, “on the way, while you’re walking, as you’re going, while you’re doing things,” so to circle men up in a fellowship hall and say process your emotions and check on each other is not the optimal way. The best way to do it, the best way to engage men, is to have them connect and build manly relationships as they’re doing significant things, as they’re doing things they care about. It’s in the doing, I think, that men really come to the fore. That’s a major difference and if churches would pay attention to that, I think it would make a big difference. There’s one other thing I’ll mention briefly and that is that the vast majority of most church staffs are female, about 80%. Where pastors have decided to change that, not to go anti-female at all, but to make sure there are prominent manly men, so to speak, on the staff, in the administration in every kind of position, people become what they behold. The church will change in its composition if the leadership has a lot of really engaged men in it. That’s been a major tactic, too.

Brett: Okay, so be action-oriented as opposed to emotions or feelings-based?

Stephen: Yes, exactly. I think that since our churches have tended in recent decades to turn a little bit therapeutic, a lot of what passes for men’s ministry is men circled up talking about each other’s emotions. That may last for a short while. It won’t carry us long-term and it won’t make us the kind of people who are changing society. That’s why I celebrate a lot of what you do because it’s about getting men connected, yes, but also getting them busy doing the right things.

Brett: Yeah, I’ve been to a few of those men’s fellowship things in the morning. The doughnuts were good, but yeah, I gave it a shot, a couple weeks and I just stopped going because I felt I’m not getting anything out of this. It wasn’t invigorating, I guess.

Stephen: Exactly, exactly. I consider myself a pretty manly guy. I hope I am. I’m okay on football and watching football. I don’t hunt. I’m not interested in motorcycles. I’m a city boy. There got to be other ways to go. Really, the key is to know your culture, know your men, and build in that direction. Keep in mind, I’m saying this to all pastors, all leaders, keep in mind that the basic nature of men, which is processing the eternal, sitting around and thinking thoughts is not the best way to engage them. We’ve got to set them in motion.

Brett: Okay. Let’s get to your book. I love how you begin your book. You talk about a moment when you were in Damascus and this is when you were a grown man and you had children. You said that was the night you became a man. Can you recount that story for our listeners? I think it’s a really cool story.

Stephen: Thanks, and I can. I was part of a relief team that was going in and out of Iraq to work with the Kurds back some years ago. On one of my trips, my papers got messed up and I got stuck in Damascus. I was there pretty much alone. There was a Syrian Parliamentarian, this was back before Syria ended up in the mess that it’s in now, who knew I was there. He was a Christian. He was concerned that I was alone and every day trying to get my papers filed right. He finally decided to have a little gathering on the roof of a hotel in Damascus. He invited a bunch of Arabs, of course, who could hardly speak English. I don’t speak any Arabic. We sat around and we ate, we nodded at each other. We said what little we could said and finally, one of the guys turned to me, in broken English, and said, “Do you have a son?” I said, “I do.” He said, “What is his name?” I said, “It’s Jonathan.” And as though he was announcing something miraculous in the room, he said, “Well, then you have a new name.” Everybody stopped and looked at him. He said, “Your name is Abu John.”

It turns out that in Arab culture, when a man has a son, it’s considered such an honorary thing, such an amazing thing for him, that he’s given an honorary name, an honorific, they call it, in Arabic. What it means is that they take the word Abu, which means father, and they put it with a shortened version of the son’s name. That’s the honorary title for the father from that point on. My son’s name is Jonathan and they started calling me Abu John. That was sweet to know, but the next thing that happened was these guys realized I did not know that. They had never celebrated that with me and so they began the manliest partying that I’ve ever been a part of. They brought out food, they turned up the music, they started dancing. Some of them had Uzis in their hands. When a guy’s got an Uzi in his hand and he’s dancing with you, he leads, so we danced and we danced. Finally, in the wee hours of the morning, they back slapped me back to my hotel and wished me well. They had spent hours celebrating me as a father.

I have to tell you, at that time, I was in my mid-30s, finishing a doctorate, had a wife, 2 children, obviously a son, had lived a pretty normal American life, military brat, football, baseball, basketball, lived all over the place. I had never, in my entire life, been celebrated as a man. There had never been a moment when men said we know who you are, we know what this means, whatever it is, becoming an adolescent, going to college, marrying, whatever it is. There had never been a ritual in my life that had commemorated and deepened the experience of some passage from one stage to another. Here these Muslim guys in Damascus, Syria, some of them probably terrorists, for all I know, I couldn’t even talk to them, dancing and celebrating me as Abu John.

It profoundly changed me. I’m a Protestant Christian. I’m not Jewish. We don’t have Bar Mitzvahs. We don’t have any ceremonies for manhood. I got to tell you, that really began to make me realize that we’re not recognizing, we’re not helping boys grow. We’re not marking these transitions with men. I’m always reminded, when I tell this story, of the African proverb from the villages that says if we do not initiate the boys, they will burn the village down. That’s very much what’s happening in our society. I wasn’t in any danger of burning anybody’s buildings or village, but I definitely was a man with an aching, empty soul when it came to manhood and that was the turning point for me.

Brett: Yeah, that’s a great point, that one of the problems, there’s lots of problems that are facing men today, this lack of a right of passage. What’s the solution to that because there’s lots of organizations and groups out there that provide rights-of-passage experiences. Is that the solution where you go to this organization or you go to … Does it need to be more organic, right, within the family or within a man’s tribe, if you want to call it, whether that’s their church or their close friends. How do you incorporate a right of passage into your culture?

Stephen: I think it does have to be done first informally. In other words, the father, the immediate men around the boy, around the young man, needs to take responsibility for it, doesn’t have to be highly organizational or even liturgical or ceremonial. When my son was about to turn 13, we had what we called a Christian Bar Mitzvah for him. We had people in who knew him and said positive things about him. We gave him a sword. Before that, I just drove up with him into the mountains. We had a big old sex talk along the way. We listened to some tapes by some wise psychologists who were talking to young boys. We went up in the mountains and we swam naked. We ate junk food until 4 in the morning and we watched old movies and we just had a great time. I think he considers both of them to have been the marking of his passage into adolescence. I tried to do the same thing when he went to college. He’s not married yet, but when he is, I’ll do the same thing then.

What we can do is simply start shifting some of these moments that we recognize as transitional moments into having an emphasis on manhood. I got married and had children, no one ever talked to me as a man, celebrated me as a man or a father. I think that we can certainly do that. Then I certainly welcome more ceremonial approaches and churches, men’s organizations. Shoot, even amongst a few friends or in a business. Certainly, anything that we do that confirms a man, confirms his journey, calls out the best in him and points him towards a value in the future, maybe gives him some symbol, some lasting things he can keep that speak of all that, I think it will really change lives. We know the value of ceremony, but we shouldn’t have to be in the military or the Boy Scouts or a highly liturgical church to have these moments.

Brett: Okay, so be proactive, be intentional?

Stephen: Yes.

Brett: You lay out what you call your manly maxims. There are 4 of them. What are those 4 manly maxims that guide the rest of your book?

Stephen: I wanted to give men a simple on-ramp for masculinity if they didn’t have one. The first one is manly men do manly things. Now of course, I’m having some fun with this. We call them Mansfield’s Manly Maxims, but the first one is manly men do manly things. The idea is simply to get men focused on the doing. I’m a little concerned that a lot of our emphasis on men in our programs and ministries and what have you really focuses on the emotional and men retreat from that. I’ve had guys say to me, when I invite them to one of our gatherings, “Do we have to hug and stuff?” They’re just afraid somebody’s going to grab them and look in their eyes and sing Kumbaya or whatever. What I want to do is get them and focus on the doing.

The second one is that manly men tend their field. The thing they’re doing is tending their field. Now this is language that comes from the Apostle Paul when he said, “I know the field assigned to me. I know what God’s given me to do.” I start asking men, “What are you responsible for? What have you been given to do,” because the opposite of great manhood is that you are irresponsible, that you’re sitting in your recliner while the house falls apart. You’re neglecting your wife who’s bitter and gaining weight, the kids who are doing things they ought not be doing, and everybody’s lonely and hurting. This is your responsibility. I think men grow in strength, authority, wisdom, and certainly honor when they take responsibility.

The third one is really the one that really galvanizes in my mind and that is that manly men build manly men. In other words, I’m all for seminars, conferences, books, every kind of thing, but ultimately, I think that noble, righteous manhood gets built into a man when he has a band of brothers. I think every man’s got to have a band of brothers and there’s got to be among those band of brothers a free-fire zone where anything can be said that needs to be said to make me better and I’ll do the same for you. Now my band of brothers, we have a lot of fun along the way. We do a lot of rowdy things, we do a lot of social service things, but we make each other better. Under the free-fire zone.

Then finally, my fourth one is that manly men live for the glory of God. I’m of the opinion that a man really can’t do what he’s made to do, do it well, do it powerfully, on his own strength. He’s got to have the gift of God, the grace of God, the guidance of God, the counsel of God, to do what he does. Those are the four. They’re not everything a man needs to know, but at least they’re the on-ramp that I think helps most men get up and running.

Brett: Yeah, the two that really stuck out to me, all of them are great, was the tending your field because I never thought of it, responsibility, in that light. I love the metaphor. Then also, the importance of building other men up because I think one of the problems in our modern culture is it’s very self-centered, right. We’re all about self-actualization, self-improvement, and we forget the other. In my experience, maybe this is your experience, too, that I’ve always become a better person whenever I’m serving others, right. For some reason, it gives me more motivation to improve myself when I feel like I’m building someone else up.

Stephen: I couldn’t agree with you more. I think that what we’ve done is we’ve defined this issue of destiny and becoming what we’re supposed to be or what we want to be in terms of a very self-focused process, like you say. I tell men look, you have a destiny, but your destiny is fulfilled by investing in the destinies of others. This is the truth of almost every great religion. It’s the truth of certainly what I believe as a Christian. It’s the truth that I see practically lived out around me. I don’t get better by getting in a room by myself and focusing on myself and looking in the mirror and just doing things to build up myself. I get better as a man as I invest in other men, as I invest in my son, my daughter, my wife, as I man the boundaries of the field assigned to me, sacrificially if necessary. I couldn’t agree more. That’s why, even in Scripture, for example, we see so many examples and direct statements where if a man’s going to be a good man to his wife, he’s going to have to lay down his life. This is the pattern. You’re absolutely right. The self-focus of our age, our society, I think works against great manhood.

Brett: All right. You have a chapter where the title is from a famous line from the Bible. It’s an exchange between King David of Israel. He’s about to die and he’s giving his final blessings on his children. He tells his son Solomon to, “Be strong and show yourself a man.” What does it mean to show yourself a man and how can men do that today?

Stephen: First of all, just taking a little bit of information about that verse, there are very few times in the Bible when the word man means the characteristics of a man, the nobility of a man, the good things a man ought to be doing, and not just males. That’s one of them. David didn’t turn to Solomon and say, “Be a male,” he said be a good, a righteous, a noble man. I think that the beginning of it is very much what you and I are discussing. I think a man needs to recognize that he’s put on earth for certain purposes and his own pleasure and personal fulfillment is not it, alone, and that he needs to invest in the lives of others, build a manly culture, bring up the boys around him, not just his own, by the way, but others, in that manly culture, and begin to do good in the world.

When men really begin to understand the gift that it is to be a man and invest that gift in society, in the young, in their wife, in noble causes, that’s when I see men really engage and other things start to get easier. It’s like your grabbing the ski rope and once you grab the ski rope and you’re balanced on the skis, now things start moving forward. Before that, you were just plowing water. A lot of guys are plowing water, but they’re not really up and moving quickly and engaged. When they make this critical change and begin to realize that manhood is a powerful thing, but it has to be invested in others to really have its power fulfilled, its purpose fulfilled, that’s when men become noble, when they become great men. It’s absolutely wondrous to behold.

Brett: Okay. The rest of your book, after you lay out your manly maxims, this on-ramp and then this ideal of showing ourselves or shewing. I love the King James version of show, shew.

Stephen: Yeah, that’s great.

Brett: That’s our goal. You dedicate chapters to virtues or ideals that we should aspire for. What I love about it is that you take a famous person or famous man from history and look at his life and how that individual represented that ideal and what lessons we can take from that. You include my all-time favorites. One of them is Winston Churchill. What virtues or ideals of manhood can Churchill teach us today?

Stephen: In all the book, what I wanted to do was take some of our heroes and show the dark side of their lives and how they overcame that. In other words, I love celebrating these guys and could’ve written real positive, happy chapters, but I decided to go to the dark side. With Churchill, perhaps the most damaging, potentially deforming thing in his life, was that his father hated him. People often don’t know this. His father was descending into a form of madness throughout most of Churchill’s young life, probably induced by a disease of some kind. Churchill was simply a disappointment to his father, even if his father had not been in some kind of medical condition. Churchill’s father treated him horribly, so Churchill lived in his shadow, lived in fear of him, lived wounded by this man.

Later in life, Churchill literally thought that his father was appearing to him and taunting him, even when he was Prime Minister of England. What I find powerful about the whole thing is that when Lord Randolph, Churchill’s father, died, Churchill had to make a decision. Am I going to live now in bitterness and regret and let that define my life or am I going to live out my father’s legacy? Am I going to pick up his discarded legacy, so to speak, because Lord Randolph ended his life pretty much in some shame and popular disrepute. Or Churchill had to think will I live out his legacy or will I just be crushed under it? He decided, as he wrote in his book, My Early Life, that he would take up his father’s legacy and cause and live it. He did that publicly for the rest of his life.

I think that’s a very defining moment in Churchill’s life. There are a number of them, as you know, but when he decides not to be bitter, not to be angry, not to live a life of regret and snarling anger, but to live out his father’s legacy and see himself as a champion of his father’s cause, I think that’s when Churchill takes major steps up towards what he would become. We all know that many men, and certainly in my own life, I could choose to, others could choose to allow bitterness towards their fathers to crush them. That’s a major defining issue right there. How will you live out a sense of family destiny? How will you extend your father’s cause in the world? I think that’s one of the things that defines a great man.

Brett: Yeah, I love the whole idea of connection to family in a way, even if your family, there’s nothing to really be proud of about your family. Maybe there’s some skeletons in your family’s closet, but using that, right, like Churchill did to go against that, I’m going to do something different, I’m not trapped by this, I can take my family’s legacy and make it something different, I think, is really inspiring.

Stephen: That’s what I’ve had to do in my own life, even. I don’t have near the level of abuse in my life that Churchill did. I come from a long line of military commanders, fairly high-ranking military commanders in American military. They were all terrible fathers, I just have to say. Love them as I do, they were all terrible fathers. I’ve sat many times with my children and said, “Listen. What we can receive from these men is not just pride in their accomplishments and their medals and their rank, but we can receive the sense that we have a family called to fight in noble causes. We have a family that really is charged with living for something passionate, maybe having to sacrifice for it.” Man, my kids eat that up. It’s not something I’m just making up. I really believe that that’s what’s passed on to them. Then I explain to them that within the soil of your greatness are the seeds of your destruction, so to speak. These guys weren’t great parents, so my kids, none of them are married yet, they’re too young, but I’m telling you, they are ready to be great parents and to overcome a negative family history. You usually can find, even in a troubled family, something to pass on to the next generation and something to live out yourself. I think that’s, again, the great benefit of Churchill’s example.

Brett: In one of your chapter’s, you make a case that men need to learn or relearn the skill of friendship. Why are friends so important in a man’s life and why is it so difficult for grown, adult men to make friends?

Stephen: It’s one of the great questions of our age. I think that most men simply friendships happen so naturally in early life that unless someone teaches them how to build friends, how to build a band of brothers, the priority and importance of it and the skills of it, then they just outgrow their friends in a sense. I don’t mean that they wouldn’t benefit from them. Most of us have friends when we’re in high school and before, playground friends up to sports, college, it’s fairly easy. You’re in dorms, you’re going to class with people, but then most guys get married, have children, get busy and a decade later, a friend is someone you call once a year if you call at all. Most guys don’t have those skills, but men need other men, number one. Most of what they’re made to do they are not made to do alone.

Women bond quickly, easily, those relationships are meaningful. Women, they can function alone usually better than men, most of the studies show, but men need other men. They need the reflections of other men. They need the insights of other men. I think that our society just isolates and causes a man to turn towards his entertainments for whatever man input he’s getting, rather than to other men. To shut off the TV and the devices, to build a band of brothers, to do noble things and to create that free-fire zone where men are speaking into each other’s lives what they need to know to be great men, I think that’s just essential.

Brett: Where do you start? Can you start at church? If you don’t have a church, can you go to work? How do you find these other men?

Stephen: Most men are in a sea of casual relationships. The art of this thing is to take the relationships you have at whatever level and move them towards relationships that are beneficial to each other and that include discussion of the serious matters of what it means to be a man. As I teach men how to do this, it’s usually just a matter of starting to turn the topics that are discussed in light conversation over lunch at work or the basketball game once in a while, whatever, turn the discussion, turn it to what do you think about this? I’m struggling with it. What do you think about that? How do you overcome that? Have you ever had to battle that? Just turn it from some of the ca-ca we tend to discuss just to bide the time and deepen them a little bit and to see who responds. If a guy responds, then now you may be moving from friendship to a real brother. Keep doing things, keep having fun, but see if this person won’t partner with you in the great project of being a man.

Sometimes, your own transparency is the best way to do this. Man, I’m on the porn all the time. Have you had to overcome that? Have you had to battle that? Or I’m just eating myself to death here, man. How do you stay trim? How do you break through the whole lethargic man thing? Just start to enlist people in purposes. Most men want to bond, they want to help their friends, they want to be tight. We’ve just simply lost the skills, so it takes one guy, I think, starting to turn the friendships he has at a very light level toward something deeper and meaningful. Then I think it starts to take on a life of its own.

Brett: Okay. I was pleasantly surprised to find humor on your list because in running this site, we hit some really serious topics and we’re really serious and earnest about helping men become better men in their lives. Every now and then, we’ll do something that’s just fun. When we do these fun things, you always have the sourpuss church-lady types who are just like, “No, you need to be serious. Manhood is a serious topic and you shouldn’t joke around.” It’s just a buzzkill. I love how you use G. K. Chesterton, one of my favorite writers, to exemplify this ideal of humor. Why is humor important in a man’s life?

Stephen: A man communicates a great deal through his humor. We not only need to lighten up and see the humorous side, Churchill said, “If we can’t see the humorous side of life, we’re not going to be able to deal with the most serious side of life,” but I really think that for most men, more is caught than is taught in the sense with humor. A little boy falls, skins his knee, he’s crying. His father says, “Did you kick that sidewalk? Don’t kick that sidewalk.” The kid stops crying. He starts to laugh. Then we can go to mom, get the medicine. This is the way men are. We comfort each other, we encourage each other. I’ve been in Iraq during the war listening as soldiers talk and they’re always talking smack and humor. It’s about lightening the load, it’s about saying we’re going to be okay. One of the philosophers said that humor is the way we explore the difference between the way things are and the way they ought to be.

I think that’s what men do inherently with humor. When they start to get into hyper-serious situations and start to get talked out of their humor, I think it’s evidence that they’re losing their souls, they’re losing their groove, they’re losing who they are on the inside. I think you’re absolutely right. We don’t need church-lady men. We need men who know how to be serious and do things in a focused way, but know how to play, talk smack, tease each other, encourage each other, and break up some of the hyper-seriousness that keeps us from really being the best we can be.

Brett: You include the virtue of wildness or being wild. What’s interesting because a lot of, when you go to church, they de-emphasize that. You got to be calm and meek and nice and don’t be wild. That’s what we’re trying to get rid of. You make the case that no, men, if they want to be good men, need to harness their wild side. Why is that?

Stephen: I think men are made for confrontation, for controlled violence. Men, we all know, you put 3 men in a break room and close the door, they’re going to fold up a piece of paper and turn it into a triangular football and wreck the room playing a football game. Men need to bark at the moon, they need to blow something up, they need to pee in the sink, they need to be outside the boundaries. I think that most men need some controlled wildness. By that, I mean they don’t need to go crazy and kill themselves hanging off a mountain, but some controlled wildness in their lives. It keeps us alive, it keeps us awake.

In a church situation, I have to say it’s a little bit weird that we go to church to worship Jesus. This is the same Jesus who was a carpenter, who got furious and flipped tables and made a whip to drive people out of His father’s temple. He was a man of passion. He wept. I can just see Him walking along the Sea of Galilee dumping Peter into the water and then starting a free-for-all. I think we’ve got the wrong image of Jesus as a guy in a bathrobe with a sheep under His arm and that’s why we all think that religion is just behave yourself. Really, I think the Spirit of God and as an example, Jesus wants us to know how to be passionate and fully engaged and full-throttle. That’s why having some wildness in your life, having some confrontation, hitting hard, I think that’s something we should never lose.

Brett: I love how you use Teddy Roosevelt to exemplify that.

Stephen: Yeah, Teddy Roosevelt is a great example for men to read about. His mother and his wife died in the same house on the same day and he was devastated. How did he recover himself? He had a little property out in the Dakota Territories and he went out there and basically lived as a cowboy for the better part of 2 years. It restored something in his soul and every historian and Roosevelt himself says he would never have been what he became if he hadn’t had that time recovering himself in wildness. I think men are overly domesticated and we suffer for it.

Brett: Yeah, I love that idea of actually getting out into nature, getting into the wilderness. Not only Teddy Roosevelt did that, who said that taking a sojourn in the wilderness was beneficial. Jack London, he said that he was in a funk and he went out into the Dakotas, or not the Dakotas, Alaska, to go pan for gold and he said that he found himself in the wilderness. Jesus started His ministry, went to the wild.

Stephen: Yes, that’s exactly right.

Brett: Something about that, so hmm, that’s a post I need to write. I thought this was interesting, you included suffering as an ideal or virtue. What is it about suffering or embracing it that can help us become better men?

Stephen: We’re living in a generation where the hardship of life itself is seen as an evil. Men really improve through hardship. Hardship’s the price of things. None of us liked the heart of hearts of football practice or baseball practice or whatever we were doing. None of us like having to do those hard things, but that’s how we improve. If we don’t see suffering as something that is part of life, then we’re going to be in trouble. We’re going to shy away from it. Embracing suffering, throwing yourself into suffering, realizing that a person’s suffering times are his best improving times, as one philosopher said, that’s how we grow.

I think men have a special gift from that, I have to say. When I go to the weight room, when I see guys working hard, doing extreme sports, it’s like something comes together in a man’s soul when he has a struggle and a battle. To convince ourselves that pleasure and comfort is the ultimate goal, and to be shocked and offended by hardship and difficulty and suffering, I think that’s going to cause us to be less than we’re made to be. I’m not a guy who wants to build a whole culture of suffering. I don’t have some weird cult idea in mind, but I do believe that we got to throw ourselves into the hardships that come our way and see them as redemptive.

Brett: You, in the book … I love this, that there’s this ideal of presence in a man or a manly presence. Can you describe what that means? I know I’ve seen men who’ve embodied that, but what do you mean by a manly presence?

Stephen: Probably the best way for me to explain it is to tell briefly the story I told in the book. That is that I had the privilege in college of spending the day with John Wooden, the famous coach from UCLA. There were many things he said to me and taught me that day as a college sophomore. The main thing I noticed was him having been a champion athlete, being this noble and famed coach, and having built all that, really, on certain solid principles, it emanated in his life. It was a presence. It was something strong that emanated from him. I don’t mean anything a cult or weird here. I didn’t see some aura wafting off of him, but he had a presence. This is going to sound very mystical, but he would walk into a room and I would see people with their backs to him straighten up and turn around to see what had changed about their immediate environment.

We went down to the big basketball arena at my college. The basketball team was practicing down there and they all stopped playing and turned in our direction. We had walked in from a direction that nothing usually happens. Some of the players just started walking over in our direction and finally they saw John Wooden and, of course, were thrilled. He had a presence. It changed my life. It was a combination of authority and a favor, a positive you-like-this-guy kind of thing. It was a weightiness. I think the main thing to say about it is when he walked in the room, there was a gentleness and a love, but there was gravitas, weightiness, there was authority. He’s a small man, by the way. I’m 6-4-and-a-half. He’s a small man, so I dwarfed him physically, but that had nothing to do with it. You wanted to get down on your knees and ask him to teach you. It’s because he simply carried with him something that you felt beyond just looking at him. I think that’s what a man has when he steps up to his responsibilities, walks in the ways of noble manhood, and exercises his authority and strength in a righteous and virtuous way. I think it emanates from his life.

Briefly, very, very briefly, I’ll tell you that my daughter used to go to a school where I had to pick her up. She said, “Dad, it’s very strange. When you walk in the door and a boy is talking to me, he’ll have his back to you, but when you walk in the door of this great big room, some of the boys I’m talking to will change. They’ll get gentler, maybe some of them get a little bit more polite.” She said, “One boy actually called me ma’am and then got all confused and looked at me embarrassed because he just felt … ” She said, “I think they feel your presence without seeing you.” I think of course, of course. I’m her father. I pray for her, disciplined her, raised her, and yeah, I have authority for her life. I think that’s how it works.

Brett: This is something you can’t fake, right, you can’t stand up straight and wear certain clothes and then talk like … This is not something you can acquire through artificial means. It requires you living a life of virtue and integrity.

Stephen: Yeah. I think it’s spiritual. I think that what men are sometimes trying to do is recreate that in the natural sense. I’m not picking on how anybody dresses or looks or whether they have tats or piercings or whatever. I don’t care. Some guys are trying to compensate for the lack of gravitas and authority in their life by developing a commanding style or something. That’s not what I’m talking about. John Wooden was dressed rather blandly. He was smaller than I was. There was nothing about him to commend him physically. He commanded, without moving a muscle, every place he was because he was John Wooden, with all that history, with everything from prayer to practice to devotion to love, all of it. Yeah, it’s not something that you can fake. It’s not something you can recreate naturally. It’s something that comes from living the life a man is supposed to live.

Brett: All right. Stephen, this has been a fantastic discussion. Where can we learn more about your book and your work?

Stephen: The best place to connect with me is Stephenmansfield.tv and from there, all the Twitter, Facebook, Pinterest, Intstagram, everything is mansfieldwrites, just mansfieldwrites, one word. I’d love to hear from everybody.

Brett: Fantastic. Stephen Mansfield, thanks so much for your time. It’s been a pleasure.

Stephen: Brett, great to be with you. Thanks for all that you’re doing, too.

Brett: Thank you. Our guest today was Stephen Mansfield. He is the author of the book Mansfield’s Book of Manly Men and you can find that on amazon.com and bookstores everywhere. For more information about Stephen’s work, go to Stephenmansfield.com.

That wraps up another edition of the Art of Manliness Podcast. For more manly tips and advice, make sure to check out the Art of Manliness website at artofmanliness.com. If you haven’t already, please check out store.artofmanliness.com. It’s our online store full of Art of Manliness swag. We got a cool coffee mug, a journal inspired by Ben Franklin’s virtue journal, posters featuring Rudyard Kipling’s poem If, and we just included or just added this cardboard skull that’s a puzzle. You put it together and when you’re done, you put it on your shelf and it’ll serve as a memento mori art piece, so you can meditate upon death and try to live life with a bit more vigor. You don’t know what memento mori is, look it up on our site. It’s a type of art that has a very fascinating history. Go there. Your purchase will support the podcast as well as the content we produce on artofmanliness.com. Until next time, this is Brett McKay, telling you to stay manly.