“Over-sentimentality, over-softness, in fact washiness and mushiness are the great dangers of this age and of this people. Unless we keep the barbarian virtues, gaining the civilized ones will be of little avail.” –Theodore Roosevelt

Sometimes when young men begin their journey into manhood, they start in on the gentlemanly side of things.

They dress in stylish, classic attire, don a fedora, and focus really hard on manners and etiquette. They hope that by doing so, others will recognize them as grown men, good men.

Take this well-meaning goofball, for example…

Yet oftentimes others cringe and chuckle at these would-be gents instead, and they become the fodder for “m’lady” memes on the internet.

Why do these well-meaning but hapless guys elicit this reaction?

The best answer to that question comes from — who else? — the Duke himself.

In one of my favorite John Wayne movies — McLintock! — he drops this incredible line:

“You’ve got to be a man first before you can be a gentleman.”

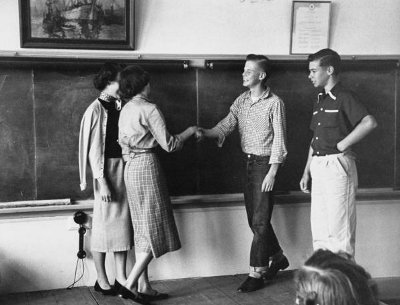

Gentlemanliness presupposes manliness. It’s a softening, a harnessing of the core characteristics of masculinity: strength, courage, mastery, and honor. A gentleman, as scholar Harvey Mansfield put it, is a manly man with polish.

The respect given a gentleman is thus premised on constraint.

A gentleman has the ability — the power, cleverness, confidence, and even the desire — to ride roughshod over your interests, muscle you aside, and manipulate you…but, he has instead voluntarily chosen to restrain himself to follow a more moral course. He’s a coiled spring, and his self-control showcases one of the timeless markers of manhood: will.

As anthropologist Paul Friedrich puts it: “The highest praise that one can give a man is that he is capable of doing harm but chooses not to.”

Gents of the “m’lady” persuasion, however, get the equation backwards. They try to be a gentleman before becoming a man. Without the structure of the hard, tactical virtues of manliness behind them, the gentle virtues shapelessly droop and sag, and fail to engender the same kind of respect.

This is because the exercise of the gentle virtues in such men requires little to no constraint or will. If an inherently mild-mannered man demonstrates mildness, it is not an act of self-mastery, but of following the path of least resistance. As 17th century writer and philosopher Francois de La Rochefoucauld put it:

“Nobody deserves to be praised for goodness unless he is strong enough to be bad, for any other goodness is usually merely inertia or lack of will-power.”

In Roman Honor, Dr. Carlin Barton points out that in antiquity, a man who lived in involuntary poverty was not respected for his frugality, and the “impotent man got no credit for continence. Rather, self-control was most to be praised where it was least expected.” Cicero got at this idea when he said: “To the degree that moderation is more rare in kings, to that degree it is more to be lauded.”

In other words, it is most impressive for a man to demonstrate virtues that he will struggle to achieve, and be sorely tested to violate.

If an awkward man who goes about his life very quietly and privately stays faithful to his wife for 50 years, we think it’s nice and praiseworthy. But, if say, a prime minister, who will have ample temptations to stray, exhibits the same loyalty, we are quadrupely impressed. In the first case, the man’s goodness may have more to do with a lack of opportunities than active restraint. In the latter case, we see clear evidence of the demonstration of energy and will.

Barton brings this distinction home by having the reader imagine a person who is trying to swear off junk food and decides to test their will by passing by a vending machine without making a purchase. If this man feels the pull towards getting a candy bar, but doesn’t act on it only because he doesn’t have the money, this will not constitute an exercise of his will, and the man will thus not feel empowered. Likewise, if he doesn’t buy a candy bar simply because he doesn’t know how to operate the machine, he will leave “not with a feeling of increased energy but with embarrassment and a feeling of inadequacy.” To enhance his willpower, the man must “approach the machine with both the necessary change and full knowledge of how to work the machine.” To gain credit in his own eyes, and in the eyes of others, he must “have both the desire and the ability to transgress.”

The man who could effectively exercise his baser and primal instincts but chooses not to, is the one who wins our honor and respect.

Conclusion

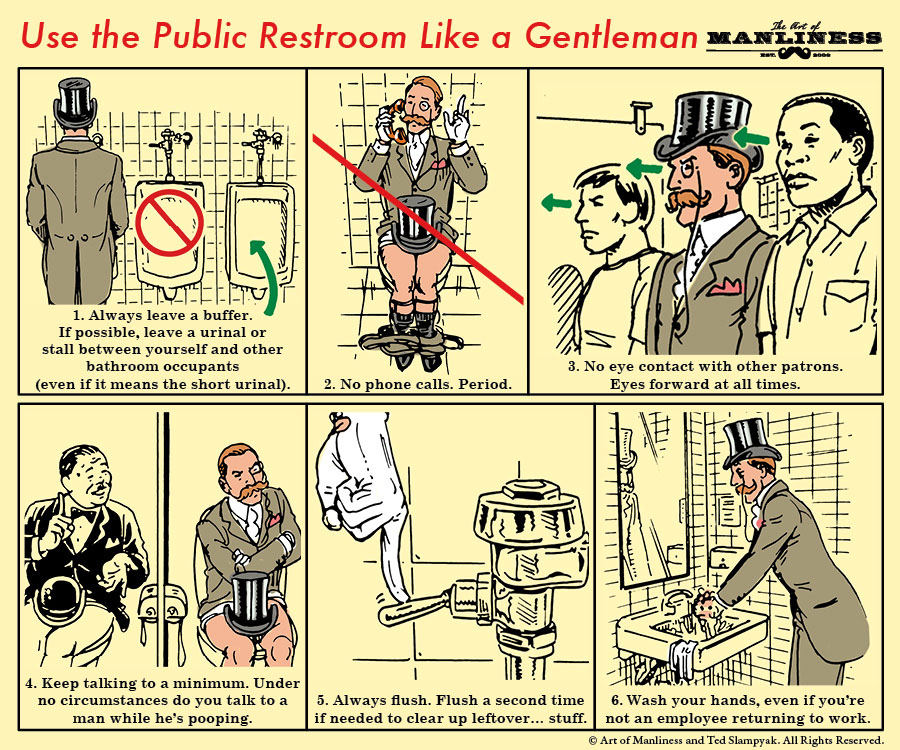

There’s definitely nothing wrong with cultivating gentlemanly behaviors — we’re obviously huge advocates for it! And in many ways learning how to tie a bow tie and mind your p’s and q’s is an easier and more accessible place to start improving yourself than developing things like strength, courage, and mastery.

But the real power behind manners and decorum lies in restraint. You have the ability, the raw thumos, and the desire to further your own interests to the greatest extent possible. But, you intentionally decide to harness that energy in order to act civilly, do good, and respect the interests of others. You could bulldoze and manipulate your way through each day and all the way to the top, but you don’t.

In the absence of this power, of this demonstration of manly will, gentlemanliness often reads as mealy — the gilding of one’s innate timidity. The lion who allows someone to pet him elicits respect; a house cat in a lion’s costume, only giggles. As Nietzsche put it, “I have often laughed at the weaklings who thought themselves good because they had no claws.”

Gentlemanliness without manliness fails to be empowering for its possessor, as it robs him both of the self-respect developed by winning the struggle between desires, and the honor of others who recognize the stakes of that contest.

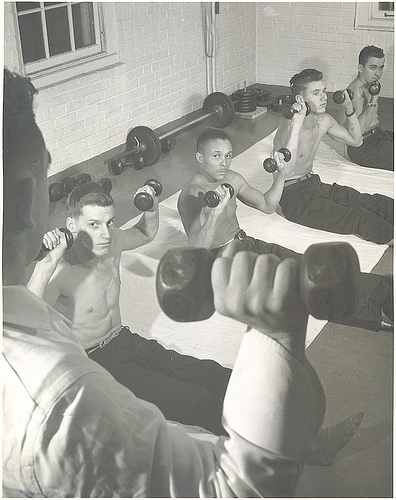

I do disagree with the Duke on one thing though: you don’t have to prioritize manliness over gentlemanliness. It’s quite possible to work on both at the same time: opening doors for ladies and your mind to masculine philosophy, practicing your table manners and your krav maga; lifting weights, and the downtrodden.

Be a gentleman.

And a scholar.

And a beast.