Editor’s note: The excerpt below comes from a book published in 1875: A Gentleman’s Guide to Etiquette by Cecil B. Hartley. Hartley has previously edified us with some incisive and amusing conversation rules. Today he offers tips on how to travel like a gentleman, especially when going abroad. While it’s no longer advisable to refer to the common folk in the countries you visit as “the peasantry,” the bulk of Hartley’s advice still holds true.

If you are going to travel in other countries, in Europe, especially, I would advise you to study the languages, before you attempt to go abroad. French is the tongue you will find most useful in Europe, as it is spoken in the courts, and amongst diplomatists; but, in order fully to enjoy a visit to any country, you must speak the language of that country. You can then visit in the private houses, see life among the peasantry, go with confidence from village to town, from city to city, learning more of the country in one day from familiar intercourse with the natives, than you would learn in a year from guide books or the explanations of your courier.

The way to really enjoy a journey through a strange land, is not to roll over the highways in your carriage, stop at the hotels, and be led to the points of interest by your guide, but to shoulder your knapsack, or take up your valise, and make a pedestrian tour through the hamlets and villages. Take a room at a hotel in the principal cities if you will, and see all that your guide book commands you to seek, and then start on your own tour of investigation, and believe me you will enjoy your independent walks and chats with the villagers and peasants, infinitely more than your visits dictated by others. Of course, to enjoy this mode of traveling, you must have some knowledge of the language, and if you start with only a very slight acquaintance with it, you will be surprised to find how rapidly you will acquire the power to converse, when you are thus forced to speak in that language, or be entirely silent.

Your pocket, too, will be the gainer by the power to arrange your own affairs. If you travel with a courier and depend upon him to arrange your hotel bills and other matters, you will be cheated by every one, from the boy who blacks your boots, to the magnificent artist, who undertakes to fill your picture gallery with the works of the “old masters.” If Murillo, Raphael, and Guido could see the pictures brought annually to this country as genuine works of their pencils, we are certain that they would tear their ghostly hair, wring their shadowy hands, and return to the tomb again in disgust. Ignorant of the language of the country you are visiting, you will be swindled in the little villages and the large cities by the inn-keepers and the hack-drivers, in the country and in the town, morning, noon, and evening, daily, hourly, and weekly; so, again I say, study the languages if you propose going abroad.

In a foreign country nothing stamps the difference between the gentleman and the clown more strongly than the regard they pay to foreign customs. While the latter will exclaim against every strange dress or dish, and even show signs of disgust if the latter does not please him, the former will endeavor, as far as is in his power, to “do in Rome as Romans do.”

Accustom yourself, as soon as possible, to the customs of the nation which you are visiting, and, as far as you can without any violation of principle, follow them. You will add much to your own comfort by so doing, for, as you cannot expect the whole nation to conform to your habits, the sooner you fall in with theirs the sooner you will feel at home in the strange land.

Never ridicule or blame any usage which seems to you ludicrous or wrong. You may wound those around you, or you may anger them, and it cannot add to the pleasure of your visit to make yourself unpopular. If in Germany they serve your meat upon marmalade, or your beef raw, or in Italy give you peas in their pods, or in France offer you frog’s legs and horsesteaks, if you cannot eat the strange viands, make no remarks and repress every look or gesture of disgust. Try to adapt your taste to the dishes, and if you find that impossible, remove those articles you cannot eat from your plate, and make your meal upon the others, but do this silently and quietly, endeavoring not to attract attention.

The best travelers are those who can eat cats in China, oil in Greenland, frogs in France, and macaroni in Italy; who can smoke a meerschaum in Germany, ride an elephant in India, shoot partridges in England, and wear a turban in Turkey; in short, in every nation adapt their habits, costume, and taste to the national manners, dress and dishes.

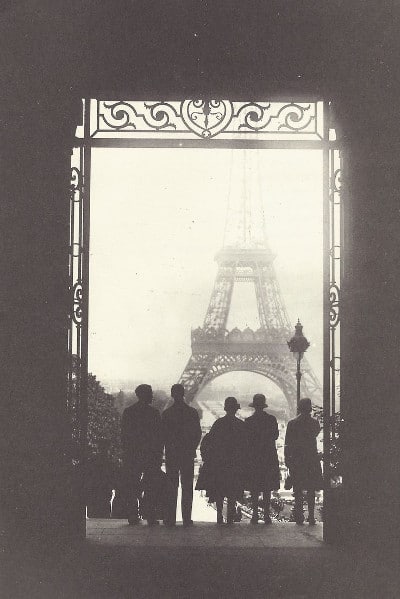

Do not, when abroad, speak continually in praise of your own country, or disparagingly of others. If you find others are interested in gaining information about America, speak candidly and freely of its customs, scenery, or products, but not in a way that will imply a contempt of other countries. To turn up your nose at the Thames because the Mississippi is longer and wider, or to sneer at any object because you have seen its superior at home, is rude, ill-bred, and in excessively bad taste. You will find abroad numerous objects of interest which America cannot parallel, and while abroad, you will do well to avoid mention of “our rivers,” “our mountains,” or, “our manufactories.” You will find ruins in Rome, pictures in Florence, cemeteries in France, and factories in England, which will take the lead and challenge the world to compete; and you will exhibit a far better spirit if you candidly acknowledge that superiority, than if you make absurd and untrue assertions of “our” power to excel them.

You will, of course, meet with much to disapprove, much that will excite your laughter; but control the one and keep silence about the other. If you find fault, do so gently and quietly; if you praise, do so without qualification, sincerely and warmly.

Study well the geography of any country which you may visit, and, as far as possible, its history also. You cannot feel much interest in localities or monuments connected with history, if you are unacquainted with the events which make them worthy of note.

Converse with any who seem disposed to form an acquaintance. You may thus pass an hour or two pleasantly, obtain useful information, and you need not carry on the acquaintance unless you choose to do so. Amongst the higher circles in Europe you will find many of the customs of each nation in other nations, but it is among the peasants and the people that you find the true nationality.

You may carry with you one rule into every country, which is, that, however much the inhabitants may object to your dress, language, or habits, they will cheerfully acknowledge that the American stranger is perfectly amiable and polite.