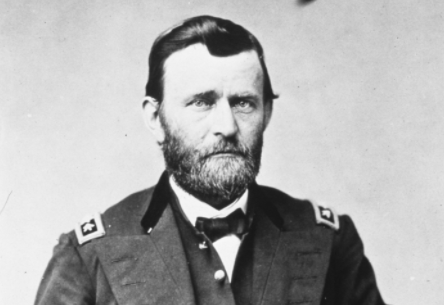

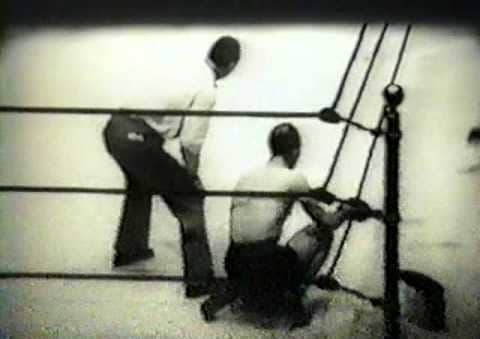

My grandfather, Johnny Paychek, poses with Joe Louis before their fight for the heavyweight title.

Editor’s note: This is a guest post from David Levien.

Fear. My grandfather faced it on a daily basis, and he did it for a living as a professional boxer back in the 1930s and early ‘40s, when the money, and the gloves, weren’t as padded as they are today. As a writer, I face fear as well. Not the physical kind, of getting punched in the face or drilled in the ribs (unless that NYC commute gets particularly nasty), but the fear of an empty page. Everyone with a presentation to prepare, a report due, a project to complete, a stock trade to make, a deal to close, an idea to put forth — in short, anyone who actually gives a sh*t about his job — knows what I’m talking about. It’s the fear of failure. That unpleasant, dry-mouthed, ball-tightening sensation that always manages to strike the moment we actually invest ourselves in the outcome of something.

My grandfather, who fought as John Paychek (though born Pacek), was well past his days in the ring by the time I got to know him. But he was a top prospect back in his prime, winning the Golden Gloves in Chicago and the International Golden Gloves, before going on the pro circuit out of the Midwest, where he racked up an impressive record and string of knockouts. He once spun an Irishman so hard with a finishing punch the guy had to be carried out of the ring with a broken ankle. That’s when my grandfather got tapped to fight Joe Louis for the heavyweight belt. (Heavyweight, although he never came within five pounds of touching 200 on the scales).

He was “invited” by promoters to show up on March 29, 1940 at Madison Square Garden. My grandfather’s camp countered that though their man was 38-3-2, he needed another year of seasoning. He was only 25 after all and it was the Brown Bomber he was going to be facing. The promoter, who knew well that Joe Louis was entering the Army and needed a quick string of money fights said: “Paychek will be there on March 29th, or he’ll never fight in the Garden in his entire career.”

So he showed up. My grandfather told me about the fight on a few occasions back when I was young. How Louis’s jab had hurt him, and he’d never been hurt by a jab. How the champ was just too fast. But the detail that stood out, the one that really stuck with me was: “I couldn’t get a sweat going in the locker room. I went into the ring dry.” People familiar with the fight game know this means one thing: fear.

I took up boxing in my early twenties, in a recreational, not professional way, at the same time I embarked on my writing career. If it wasn’t completely conscious at the time, it certainly was no accident. The discipline required for each, one more physical, the other more mental, was analogous to me. A boxer squares off with an opponent who is trying to put him down. A writer faces a cursor blinking on an empty page like an accusation. What do you have to say? Why does anyone want to hear it? What makes you think you’re good enough? Huh? A writer battles with the fear that nothing worthwhile will come, maybe nothing at all, that something started well won’t turn out, or that someone else will do the same idea first, or better.

Regardless of career path, every man faces his own challenges in the workplace, and the metaphor that a job, whether temporary or one’s life work, is a fight on some level (especially in today’s economy) is apt. In some cases the opponent is an individual — an actual competitor who must be bested in order to win the account or contract, a vendor looking to take advantage. In other cases, the challenge is an indifferent marketplace, employees, an organization that resists falling in line, a boss who can’t see your true worth, or even an unappreciated idea. Self-doubt can be a constant foe. Am I good enough? Is my idea sound? Am I doing my best, or at least the best I can right now? Nearly all of the time, the self — one’s own willingness to be bold enough or to do the hard work, to prepare, to read and re-read all the documents, to scour the data, to do the research necessary to execute the job correctly — is the true adversary.

The snick of the jump rope and the pop of the pads greet the boxer when he arrives at the gym. He has to train with metronomic regularity, or he’ll suffer for it on fight night. In my case, the writer wakes up to blank notebook pages to be filled with free writing. He has to return to his project each morning and make steady progress or he’ll never get to the end. Just as the boxer trains to instill the skills, but also the confidence he’ll need in the ring, a writer writes every day to build his craft, not only to create greater effects on the page, but to lay in the strength and self-belief that will see him through the dark, confusing times. The boxer catalogs his experience, round by round, bout by bout, and draws on that experience in the big ones.

In a similar way, I can now look back on a series of books and films I’ve written, and use that body of evidence to dial down what might have been full-blown panic back in the beginning to a level of useful edge. We all have to find rituals and disciplines with which to build our strength (both inner and outer), our power, and our courage. Because there will be fights, and we’d better be ready. It doesn’t have to be boxing, of course. It doesn’t even have to be physical. Maybe it’s meditation, or staying up late or waking up early to think about your workday, your month, your year, your five-year plan. Perhaps it’s a seminar that will give you an edge, or finding a mentor who can give guidance and share the benefits of his wisdom. Whatever it is, try and do that extra thing, so you can draw on it when you find yourself on the ropes.

My grandfather was a young guy with some skills who faced a moment that was bigger than he was. It didn’t go well for him — a few knockdowns in the first and a KO by way of vicious hook in the second. But I’ll always admire that he stepped in there against an all-time great, to say nothing of his getting back up after those first few visits to the canvas. When it was time for fight or flight, even though some of his body’s systems were suggesting one, he managed to do the other.

A writer has to be a fighter at heart, to deal with the failures and the rejections, and like a fighter, he’s going to lose some, but he’s got to keep going. Whatever the job, whatever the pursuit, there will be moments when you taste some leather. The more you care, the more it hurts. The fighter’s way of laying in the training and converting the pain into motivation is universal. And when it gets hard, when the idea of quitting might start to glow like a lantern in the distance on a dark night, it inspires me to remember that if my grandfather could do what he did that night in the Garden, then I can at least try my damndest to answer the bell in my own way.

____________________

Writer/Director/Producer David Levien has worked on some of the most influential movies of the past two decades, among them Rounders, Ocean’s Thirteen, The Illusionist, and Solitary Man. Levien’s novels have been nominated for Edgar and Shamus awards. In 2014, he won an Emmy Award for directing This Is What They Want, a documentary in ESPN’s lauded 30 for 30 series. His newest book Signature Kill has just come out to rave reviews.