In the modern age, we know more than ever before, and the information has never been so readily available.

And yet individuals and organizations often fail to deliver on the promise of all this knowledge. In fact, we are often the victim, and the architect, of head-slapping displays of incompetence when it comes to delivering what’s been promised, or forgetting routine things that have no business being overlooked.

Why is there so often this mismatch between potential and application?

As our knowledge about the world increases, so too does its complexity. And as complexity goes up, so do the opportunities for failure.

Medicine is a great example of where our increased knowledge has made things better, but also more complex, with more possibilities for snafus. Before the mid-20th century, medicine was pretty simple. There wasn’t much specialization; when you went to the hospital, there was usually one doctor and a few general nurses overseeing your care.

Now when you go to the hospital, you can have several teams taking care of you. Nurses, nurse technicians, radiologists, dieticians, oncologists, cardiologists, and so on and so forth. All these people have the know-how to deliver top-notch healthcare, and yet studies show that failures are common, most often due to plain old ineptitude. For example, 30% of patients who suffer a stroke receive incomplete or inappropriate care from their doctors, as do 45% of patients with asthma, and 60% of patients with pneumonia.

It’s not ignorance or ill-intent that causes these failures. Knowledge abounds among our healthcare practitioners. The problem is that because medicine is more sophisticated and specialized, applying that knowledge correctly across several teams is harder. There are multiple streams of information to remember and manage.

And the tragic thing is it’s often the “stupid” simple stuff that gets people killed or keeps them in the hospital for longer than they needed to be. I have an acquaintance who ended up in the hospital for two weeks because he got the wrong heart medicine. The problem was ultimately one of miscommunication — a basic thing you think would be a given, seeing as how hospitals can transplant human faces and whatnot.

This isn’t a problem unique to medicine, of course. It exists across almost every domain of life, be it business or science or even just getting things done around the house or on your car. More and more of our work requires coordinating different teams to get a task done. If you work for a big corporation, you’re likely collaborating with a whole host of people to complete a project. And just as in medicine, you’ve likely seen projects delayed or even fail not because of lack of know-how, but due to head-scratching ineptitude.

The crux of this problem is while the world around us is becoming more and more complex, we’re still stuck with a brain that hasn’t changed much in 100,000 years. Sure, we’ve figured out ways to off-load memory storage to books and computers so we can know more; we just haven’t figured out a good way to overcome our evolved biases, cognitive flaws, and intrinsic forgetfulness. And so, despite owning a brain brimming with ever more knowledge, we continue to make stupid mistakes.

But what if there was a tool that could help us avoid misapplying knowledge and overcome cognitive flaws the same way data storage has helped us be more informed?

Well, there is one, and you’ve probably used it today.

The humble checklist.

The Power of Checklists in Action

When you hear the word “checklist” what probably comes to mind is your daily/weekly to-do list. With a to-do list you write out your more urgent tasks, and work your way through them. As you cross some things off, you add new tasks to the list.

To-do lists are definitely awesome for getting things done, but there’s another kind of checklist as well – what I call the “routine checklist.” With a routine checklist, you write down all the steps/tasks needed to complete a certain project or process. The list of tasks never changes. You use the same checklist over and over again, every time you do that particular process/project.

While the checklist may sound, well, awfully routine, it’s a tool that can truly help you survive and thrive in our modern, complex world. Don’t believe me? Here are just two of the many examples surgeon and author Atul Gawande highlights in his book, The Checklist Manifesto, that demonstrate the surprising power of checklists:

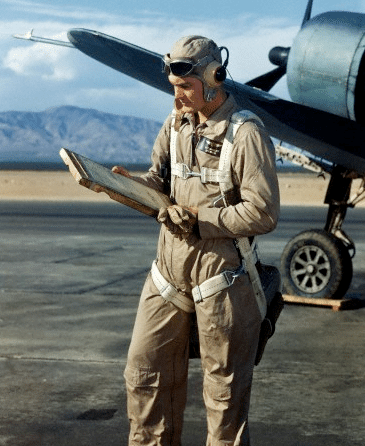

B-17 Bombers. You’re likely familiar with the iconic B-17 “Flying Fortress” Bomber. But did you know if it weren’t for a simple checklist, it never would have gained its renown in WWII? In the 1930s, the U.S. Army Air Corps held a competition for airplane manufacturers vying to secure a contract to build the military’s next long-range bomber. Boeing produced a plane that could carry five times as many bombs as the army requested, and flew faster and further than previous bombers. On the day Boeing demonstrated its Flying Fortress, the plane lifted off the tarmac, stalled at 300 feet, and then crashed in a fiery explosion.

Investigators discovered the crash wasn’t caused by a mechanical malfunction, but rather pilot error. The problem was while the new bomber could carry more and fly faster and further than any other bomber in history, it was also an extremely complex plane to operate. To fly it, a pilot had to pay attention to four different engines, retractable landing gear, wing flaps, electric trim tabs, and much, much more. Because the pilot was so preoccupied with all these different systems, he forgot to release a new locking mechanism on the elevator and rudder controls. Overlooking something so simple killed the two men at the helm.

The Air Corps concluded that the Boeing model was just too complex for pilots to operate and so awarded the contract to build its long-range bombers to another company.

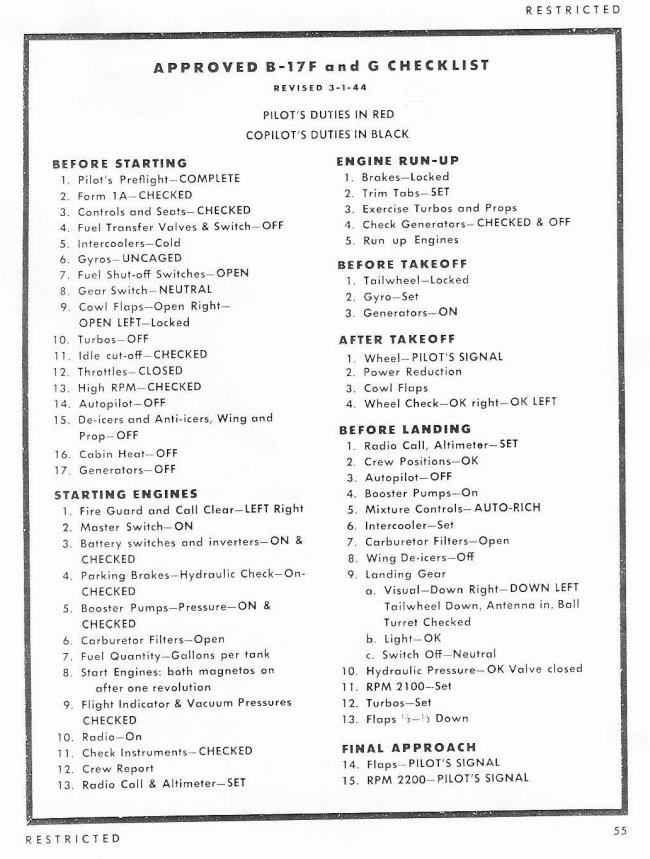

But the military still bought a few Boeings to experiment with. Some test pilots believed the Boeing bomber was a much more effective warplane and got together to figure out how they could get pilots to fly it. Instead of requiring more training, the test pilots implemented a simple pre-flight checklist. It spelled out all the basic tasks that were needed to fly the plane successfully, like checking to see if the battery switches and radio were on before taking off. By implementing the checklist, pilots flew the Boeing bomber 1.8 million miles without a single accident. Thanks to a “stupidly” simple checklist, the Army ended up ordering thirteen thousand Boeing bombers and the B-17 soared into the annals of wartime history.

Construction. Take a moment to think about the complexity of building a towering commercial skyscraper. Teams of contractors and subcontractors work on different parts of the building at different times and hundreds of specialists are needed to get the job done: engineers of all kinds, electricians, plumbers, carpenters, elevator installers, excavators, window installers, environmental experts, security experts, geologists, cement pourers, steel manufacturers – the list goes on.

Yet despite the complexity of modern construction, companies are putting up bigger buildings faster than ever with an annual structural failure rate of less than 0.00002 percent.

How?

Checklists, of course.

Every construction job begins with a massive checklist of tasks that have to get done and each task has an accompanying deadline. While that to-do list plays an important role in ensuring stuff gets done, an equally valuable checklist is also used. Called a “submittal schedule,” it centers on communication. The submittal schedule details which project managers need to talk to which project managers during a specific phase and about a specific process. The submittal schedule’s purpose is to get teams that are working on different yet co-dependent projects to regularly connect so they can discuss any potential sticking points. For example, there might be an item on the checklist for carpenters and plumbers to meet up at a specific time to discuss their progress on their respective tasks. Maybe a problem has come up with the pipes that affects when the carpenters can get started on their work, but perhaps there’s something the carpenters can do to help the plumbers. The trick is to keep each other in the loop so each respective team can take care of these “known unknowns” as quickly and as effectively as they can. Once the teams talk, they check the communication task as complete, and move on with their work.

Modern construction is a perfect example of how checklists can help us manage the complexity of modern life. In today’s complex and interdependent world, failure to communicate is the cause of most of our ineptitude. Different people or teams have different bits of knowledge to complete a project, but failure to communicate that information between the various groups and individuals can cause big-time breakdowns that lead to setbacks, or abject failure.

Benefits of Checklists

Everyone knows why to-do checklists are so useful: they help you get things done. But there are also particular benefits to routine checklists that have made them an effective tool for navigating complex systems. Here are 4 of them:

1. Checklists verify that the necessary minimum gets done. With increasing complexity comes the temptation to skip over the stupid simple stuff and instead focus on the “sexy” parts of one’s work and life. Because the stupid simple stuff is so stupid and simple, we often fool ourselves that it’s not important in the grand scheme of things. But as we’ve seen, it’s often our most basic tasks that can spell the difference between success and disaster.

Checklists act as a check against our ego, and remind us to make sure the stupid, simple, but absolutely necessary stuff gets done.

2. Checklists free up mental RAM. People often bristle at using a checklist because it feels constraining. They want to be flexible and creative, and the checklist seems to take away their autonomy. For this reason, implementing checklists among surgeons has proven difficult, even though studies show checklists dramatically reduce the number of preventable, life-threatening errors. Surgeons feel that their work requires an intuitive judgment that’s born from years of training and experience and can’t be reduced to a simple checklist.

What these stubborn surgeons fail to see is that checklists provide them more freedom to exercise their professional judgment. They don’t have to think about remembering to do the stupid simple stuff because there’s a checklist for that. Offloading the need to remember basic tasks frees up the brain to concentrate on the important stuff. For surgeons, this means they’re left with more mental RAM to focus on handling unforeseen problems that often come up when you’re slicing someone open.

Checklists don’t replace judgment, they enhance it.

3. Checklists instill discipline. Checklists continue to play a vital role in aviation. Every time pilots and co-pilots take off and land, they verbally go through a checklist. A lot of what they review is of course the stupid simple stuff, but it’s important stupid simple stuff. When you’re responsible for the lives of 120 passengers, you have to have the discipline to make sure you do even the small things right. If there’s ever an incident in air, investigators will go back to see if the pilot and co-pilot went through the checklist. There’s no fudging with it. You either did it or you didn’t.

Because checklists provide a binary yes/no answer, they instill discipline in the person that uses it. Research shows that giving someone a checklist for a task increases his or her chances of completing it. There’s something about having a checklist that spurs people to get stuff done. Perhaps it’s the dopamine rush that comes with checking something off, or the concreteness checklists provide, or a combination of the two.

4. Checklists save time. A common complaint about checklists is they take too much time to go through. But running through a checklist need not take very long, and research shows that doing so will actually save you time in the long run. Because checklists can prevent errors caused by skipping basic steps, you spend less time fixing mistakes and more time doing constructive work.

How to Make an Effective Checklist

Simply making a list of the steps involved in a certain task does not an effective checklist make. Here are some tips from The Checklist Manifesto to help you create a truly useful checklist:

1. Investigate your failures and look for “killer items.” Take a look at your work or even your personal life. Are you less productive at work than you’d like to be? Does the house always seem a disaster? Examine why you aren’t getting the results you want. Look for failure or friction points in the tasks you do routinely. These failure or friction points will serve as the basis for your checklist.

2. Focus only on the “stupid” essential stuff that’s frequently overlooked or skipped. You don’t need a checklist that lists every single step on how to complete a task. That renders a checklist useless. Instead, just focus on putting down the “stupid” but essential stuff that you frequently miss. Your checklist should have no more than 9 items on it. The shorter the better.

3. Decide if you need a “communication” checklist. Most checklists are likely procedural (they lay out things you need to do), but some tasks or projects are so complex that communicating with others becomes vital to managing all the moving pieces. In such a case, create a dedicated communication checklist and make sure it includes who needs to talk to whom, by when, and about what.

4. Decide if your checklist will be a “DO-CONFIRM” or “READ-DO” checklist. With DO-CONFIRM checklists, you do your job from memory and experience, but then at a certain point you stop to go through your list to verify you did everything.

READ-DO checklists require you to read and perform a task on the checklist before you can move to the next task.

If you need more flexibility, go with DO-CONFIRM; if you need more exactness go with READ-DO.

5. Test your checklist in the real world and refine as needed. If you’re still experiencing the same failures or if the checklist makes work cumbersome to the point that it becomes a stumbling block, then you need to refine your checklist.

Examples of Checklists From My Own Life

If you’re grooving on the idea of using more checklists in your life, but aren’t sure where to apply them, here are some examples of how I have personally used this tool that will hopefully get you thinking about where you might employ them yourself:

Law school exams. I stumbled upon the power of checklists for managing complex problems while in law school. In a law class, a single three-hour long essay exam determines your final grade. You’re presented with one or two complex hypothetical situations and are required to identify and analyze all the legal issues in them. To excel on law school exams, knowing the law isn’t enough. You have to be adept at applying it to different legal scenarios.

The way I prepared for these tests was to take lots of practice exams under the same time constraints as the real deal. Professors often post their old law exams online so I used those. The most important part of these practice sessions was the review afterward. I’d look at my answer and compare it to the professor’s answer key. It allowed me to see which issues I missed and any analysis I forgot to include. After two or three practice exams I began to see patterns in my failures. I’d make the same mistakes over and over again, and it was often due to overlooking stupid stuff.

So I made a checklist for myself to go through after I completed each essay question to make sure I covered those issues that kept popping up in my practice sessions. I’d test my checklists on other practice exams and refine them as needed. Come actual exam time, I’d always end up catching something I missed by going through my checklist.

Filming YouTube videos. Over the past few years, I’ve worked with Jordan Crowder to produce more video content for our YouTube channel. While Jordan edits and films many of our videos, I’ll do some filming myself sometimes and then send him the footage to edit. Over the years, I’ve run into some regular problems that have mucked up the filming process. They’re stupid simple things that I just forget about. So I made myself a “READ-DO” checklist of things I need to do before I start recording, and it has saved me boatloads of time:

- Check if camera battery is fully charged and that you have packed an extra fully charged battery.

- Check if you’ve packed wireless mics and that the battery is fully charged. Check for back-up AA batteries.

- Check if SD card is in camera. Check that you’ve packed an extra SD card.

- Do sound check on wireless mic before you start recording.

- Make sure all background music is turned off.

Travel checklist. I also have a checklist that I use before I leave on an extended trip. It’s kind of a combo of a to-do list and a routine list. It’s stuff I need to get done, but I use the same list every time. And it’s a DO-CONFIRM checklist: I do my prep from memory but then check the list before I leave to verify that I took care of everything essential. These are the things that I’ve had the most trouble remembering in the past, so they’re on my list:

- Ask a neighbor to get mail and newspaper

- If neighbor can’t get mail, put hold on mail and newspaper

- Put up away messages on email

- Get cash

- Pack

- Lock doors

- Turn off furnace/air conditioning

- Set alarm

- Check if everyone has their ID for the airport

- Bring phone charger

Mental checklists to improve thinking. Berkshire Hathaway vice-chairman Charlie Munger uses a mental checklist of biases and cognitive flaws that he reviews before making any big decision to ensure he’s thinking clearly about it. He’ll go down the list and ask himself if any of these biases are clouding his thinking and what he can do to mitigate it. Ever since I’ve learned about that, I’ve tried using something similar in my life. Crafting this list is still a work in progress for me, but here’s what I have so far:

- Am I making this decision due to the sunk cost fallacy?

- Does the person who’s recommending a course of action for me have an unitentional self-serving bias in making that recommendation? (i.e. “Never ask a barber if you need a haircut.”)

- Am I making this decision because of confirmation bias?

- Is my judgement of someone’s behavior due to the fundamental attribution error?

- Is my anchoring on one particularly attractive trait in something causing me to ignore the bad traits?

- Am I fooling myself into thinking I can’t fool myself?

- Have I distorted my memory of what happened to fit my actions more neatly into a narrative?

- Is the gambler’s fallacy coloring my decision?

- Is cognitive dissonance leading me to rationalize and excuse my mistakes?

(If you’re interested in what some of these terms mean, David McRaney’s You Are Not So Smart is a good place to start.)

In addition to the above examples, I’m trying to develop more checklists for my work and personal life. I’ve looked at some re-occurring sticking points that happen throughout the day and have been experimenting with whether a checklist can help with it. My challenge to you this week is to take a look at your own life and see if there are areas where a checklist would help out. It’s not a sexy tool, but it’s a powerful one!

________________

Source:

The Checklist Manifesto by Atul Gawande