“A college education unfits rather than fits men to affairs.” –Andrew Carnegie, 1901

Over one hundred years ago, one of the richest and most successful men in America, Andrew Carnegie, thought that college was not only unnecessary, but actually detrimental for the average young man. At that point in our country’s history, only 4% of young people attended college. What changed?

In America today, it’s often assumed that most young adults will attend college after graduating high school. It’s just what you’re supposed to do. Even discussing anything to the contrary is often met with backlash, as is evidenced in the comments on a guest article we published earlier this year about testing out of even a semester of college. The reality, however, is that the situation in America here in 2014 for graduated high schoolers is much different than it was 100 years ago, 50 years ago, and even just 10 years ago.

This is the first of three articles that will take a look at whether our modern ideal – that college is the best path for everyone – is really valid. While there are plenty of alternative college options out there (which we’ll discuss in-depth in the third article in the series), we’ll largely be discussing the necessity of the 4-year college, as this is often seen as the “best” option after high school. It’s what the kids with the highest test scores do, it’s what supposedly gives you the most income potential, and it still carries a prestige that simply isn’t found in community colleges or trade schools.

You may be thinking, “Of course college is necessary!” and you certainly wouldn’t be alone in that. There is, however, a growing population, both young and old, that is starting to question this assumption. This is even evidenced just by a quick look at what Google wants to fill in when searching “is college…”:

Six of those top 10 results are questioning the worth and necessity of college! Clearly there are people asking this question, even if they’re in the minority for the time being.

As of 2013, there are about 14 million students enrolled in 4-year institutions, and that number is expected to jump up to 20 million in the next few years. While some of these are older, non-traditional students, most of them are made up of the 70% of high schoolers who attend college immediately after graduating (this particular statistic includes 2- and 4-year colleges).

Over two-thirds of all high school students believe (whether on their own or through cultural pressures) that college is the best choice for them following high school. The college experience has become as American as apple pie and baseball. It’s just what you do.

Is it really the best option, for every single person though? It wasn’t always the case in the history of America that the majority of 18-year-olds would trot off to college in the fall. In fact, it’s actually quite recent, only taking hold from about the 1920s and on (and some would argue much later than that, even). For over 300 years prior, college served a pretty specific demographic of people, rather than being a universal, automatic stop on the conveyer belt to adulthood.

Our goal with this series is not to bash the college experience. Rather it is to present objective reasoning as to why a particular student may or may not consider attending college. What we want to do is examine and soften the iron-clad assumption that it’s simply what you do. In the end, students should thoughtfully engage their reasons for attending college, and make conscientious decisions. Certainly, that’s hard to do as an 18-year-old, but it is possible, especially with support from parents and mentors.

*Note: While there are technically differences in the definitions of the terms “college” and “university,” in this series of articles, I’ll use them interchangeably. For what we’ll be discussing, there is no real need to differentiate, as they’re both essentially known as 4-year learning institutions.

The History of College in America

In this first post, we’re going to take a brief look at the history of higher education in America. What was it that changed in the last century that created the modern demand for the college experience? How did it transition from an institution for the wealthy upper echelon of society, to a near-universal rite of passage?

As author Daniel Clark asks in Creating the College Man, “Might not our present debates about the purpose and place of college education (what value it adds) be advanced by a deeper understanding of the genesis of the American embrace of college education?”

As is evident throughout most Art of Manliness articles, we rely on history to inform the fullest understanding of the present. To ask the question of whether or not college is necessary, we need to first see how we got to this point. It certainly wasn’t always necessary…has our society changed enough for that experience to now be an unassailable requirement, or should we perhaps question some of the norms we’ve come to believe? Below you’ll find an overview of the history of higher ed in America. Let it inform you about our present situation, and provide deeper understanding of how and why attending college came to carry the weight that it does today.

A Timeline of Higher Education Pre-1944

We’re going to break down this timeline of college in America to pre-1944 and post-1944. We’ll find out why exactly further on, but for now, learn a little bit about how the typical American college came to be.

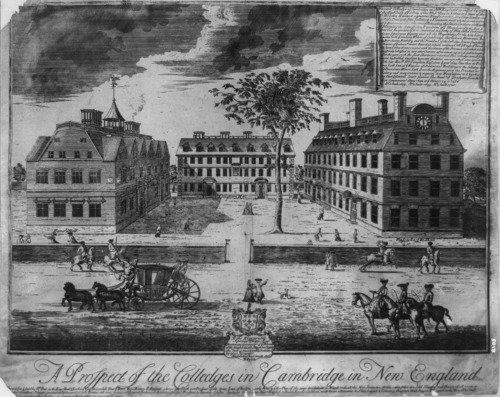

Harvard, the first college founded in the American colonies.

1636 — Harvard founded. It was the first college in the colonies that were to become the United States. It roughly followed the model of Cambridge and Oxford in England (two of the world’s oldest institutions), as the Massachusetts Bay Colony had many residents who attended those schools. To a large degree, Harvard focused on training clergymen in order “to advance learning and perpetuate it to posterity, dreading to leave an illiterate ministry to the churches.” Training clergymen wasn’t the only emphasis though; of Harvard’s first 500 graduates, only about half went into ministry. There were other possible studies that could lead to careers as public officials, physicians, lawyers — other leadership roles in local communities. Students of early Harvard were studying a largely classical (what we’d now call liberal arts) curriculum of Latin, Greek studies, civic law, theology, etc.

1693 — It took almost 60 more years for a second college to be founded, William & Mary. It was an Anglican institution, and required students to be members of the Church of England. In addition, professors had to declare their adherence to the Thirty-Nine Articles. While you could study philosophy as well as “natural” philosophy (math, physics, etc.), this education was mostly in preparation to become a minister.

1700 — Tuition is up to about 10 shillings per quarter, which amounted to the cost of about a pair of shoes and two pairs of stockings. This cost was not prohibitive for most families. So, why didn’t more people go to college? It was more about practicality. The family farm or business could ill afford to lose an able-bodied young man for a period of multiple years. It not only was a couple years of lost income, but when living costs were factored in for students (almost entirely paid for by parents), the cost just was not worth it for the vast majority of colonists. It was an elite group of people who attended; in fact, for its first 150 years, Harvard graduates were listed by the family’s social rank rather than alphabetically.

1776 — By the time of the Revolutionary War, there were nine colleges in the states. Enrollment up to this point was still quite small (rarely ever exceeding 100 students per graduating class), but those who did attend college became community and political leaders. Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and George Washington are just a few of our college-educated forefathers. It should be noted that not all early college-educated men earned completed degrees — there was no stigma in “dropping out,” so, many of them attended for a year and two and then left to pursue careers. As John Thelin notes in A History of American Higher Education, “Going to college was not a prerequisite to the practice of the learned professions. Learning often took place outside the academy in various forms of apprenticeship.” So why did people attend college? It was about prestige, status, and civic leadership/power.

Early 1800s — The number of colleges in America doubled in the previous quarter-century to around 20 institutions. While enrollment has gone up, it’s still not popular amongst common folks. Tuition was fairly low and entrance requirements were flexible, so why didn’t more attend college? Thelin explains:

“Given that tuition, room, and board charges at many colleges were minimal, why did more young men and women not opt to enroll? The American economy provides two very different explanations. On the one hand, many families could not afford tuition payments, however low; more important, they could not afford the forgone income or forfeited field labor of an elder child who went from farm to campus. On the other hand, in those areas where the American economy showed signs of enterprise and growth, a college degree—even if affordable and accessible—was perceived as representing lost time for making one’s fortune. This perception held for such high-risk ventures as land development, mining, and business. It also pertained to the learned professions of law and medicine, where academic degrees were seldom if ever necessary for professional practice. The college in this era, then, was but one means of finding one’s place in adult society and economy.”

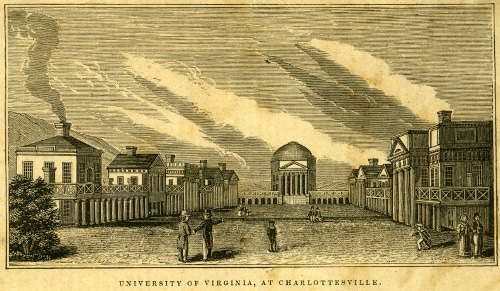

Jefferson’s vision in founding UVA, was “to establish in the upper country of Virginia, and more centrally for the State, a University on a plan so broad and liberal and modern, as to be worth patronizing with the public support, and be a temptation to the youth of other States to come and drink of the cup of knowledge and fraternize with us.”

1825 — University of Virginia opens. This is an important event because the building and founding of the university was championed by Thomas Jefferson, who had a lasting impact on education in America.

After his presidency, Jefferson tackled the issue of education. He wanted to move away from the religious ties to college, and also wanted it to be paid for by the general public so that students who were less wealthy could attend. While he instituted other colleges in Virginia, those functioned more as high schools — teaching science, agriculture, how to make things by hand, etc. But UVA was a different matter. It was to be a proper university. Here, students would become lawyers, doctors, scientists, and government leaders. The university would educate the cream of the crop — those who were destined and guaranteed to be leaders in the community. To prove its separation from the church, in a physical manner, the university was centered around a library rather than a chapel. Jefferson’s hope was that anyone could freely attend, as long as they had the ability — a perfect meritocracy. Well ahead of his time, free public education (in primary schooling) didn’t overtake private education until the late 1800s.

1850s — Although commerce is becoming an increasingly large part of the American economy, there are only a handful of business-specific courses offered by US colleges. At this point, business professions were still seen primarily as on-the-job learning, and if anything, people took a 6-week course in bookkeeping or even business correspondence. I point this out because in just a few decades, university presidents would realize the potential money to be had in the growing constituency of future businessmen in America. And today, business is far and away the largest field of study in college, with about 20% of all degrees conferred being in business fields.

Iowa State University. Land-grant universities coupled practical vocational training with classical studies.

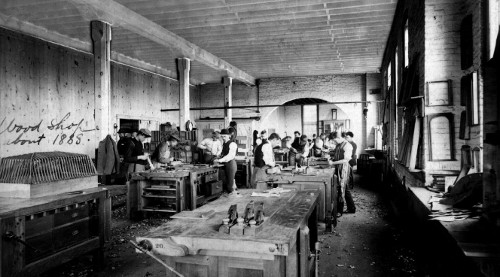

1862 — The Morrill Land-Grant Act is passed into law by President Lincoln, which allowed states to freely receive land for public universities — so-called land-grant colleges. This bill was created in response to the industrial revolution and the myriad of “practical” professions this innovative time period was creating — machinists, farmers (as a vocation vs. a lifestyle), even engineers. The purpose of these land-grant institutions was:

“without excluding other scientific and classical studies and including military tactic, to teach such branches of learning as are related to agriculture and the mechanic arts…in order to promote the liberal and practical education of the industrial classes in the several pursuits and professions in life.” —Title 7, U.S. Code

Mechanical Building, University of Illinois

So they wouldn’t exclude classical studies, but they would add in more practical pursuits. It was at this time that college truly transitioned from being about civic leadership and classical (read: philosophical) learning to being about vocational learning. People were starting to realize that in a changing, industrial world, certain professions had specific educational needs. Ultimately, 70 U.S. institutions were created as a result of this act (including the second Morrill Land-Grand Act in 1890). The Morrill Land-Grant Act is often called the singular source of practical and affordable higher education.

1880-1910 — The country sees many more universities emerge in these “decades of industry.” Part of the reasoning for this is that universities ended up with more and more leaders of industry on their boards, who in turn asked the question, “Why can’t college be run like a business?”

This period also sees the buildup of great wealth among prominent figures and therefore more discretionary income. This led to new levels of philanthropic generosity, and colleges topped the list of institutions to give to. Remember, although there weren’t a great number of college alumni, many civic and business leaders had attended college. They gave back to their institutions. They also used their connections in this golden age of illustrated magazines to work their PR charm and get the physical beauty of many college campuses out in front of the nation’s eyes.

1900 — Although degrees are conferred after four years of education, it’s still the case that the majority of students leave after just two years of school. After that point, they could earn their L.I. Certificate (License of Instruction), which would allow immediate employment in various fields. In fact, at William & Mary, 90% of students between 1880-1900 ended their studies after two years.

It’s also still the case that tuition prices are low enough at the majority of colleges to not be prohibitive. College degrees are not required for most professions, so the real struggle for university administrators (and wealthy donors) of this time period was actually convincing young men that college was even a necessary pursuit.

Colleges built architecturally-pleasing buildings to attract students. They still contribute to higher education’s romantic allure.

Believe it or not, part of this convincing came in the form of campus architecture. New wealth as well as technological advancements in how buildings were constructed led to universities becoming more and more visually appealing to potential students. Whereas many colleges in the past had one or two prominent buildings, they could now make an entire campus extremely polished and even luxurious.

1900 — College Entrance Examination Board formed (now known as just College Board). This organization seeks to standardize college entrance requirements in order to make sure the “product” of US colleges is up to par. Eventually, it’s this organization that owns and operates SAT testing, CLEP testing, and the Advanced Placement (AP) program.

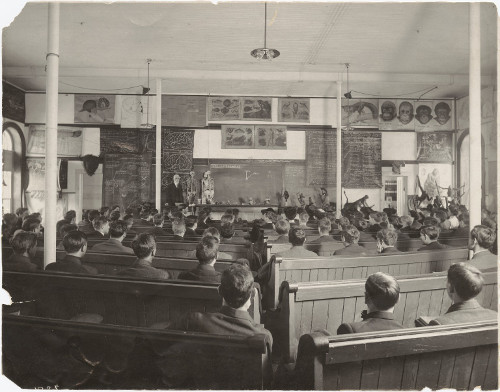

Lecture at Cornell University, 1910. In the early 1900s, lectures and seminars began to become the standard form of teaching on campuses.

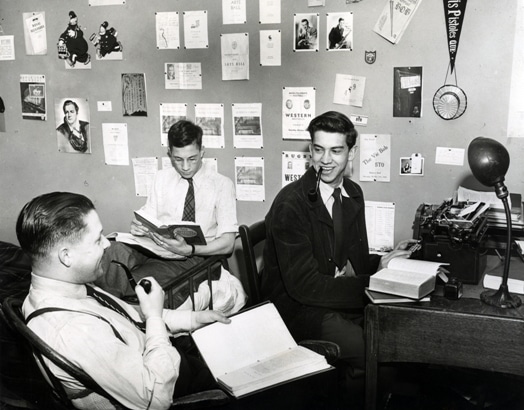

Early 1900s — Thelin lays out a set of characteristics that we see emerge that come to define the great modern American university of the time. You’ll notice they carry an immense likeness to universities today:

- Philanthropy on a large scale. Wealthy donors gave institutions a financial base that they had never before had, giving them the opportunity to grow, almost as businesses.

- Strong university president. In this age, presidents functioned almost as entrepreneurs. They were civically involved, politically involved, and leaders in their communities.

- Full-time professor-experts. As universities gained stature and wealth, professors were soon expected to devote all their time to their university. Full-time professors became the norm, and were expected to continue to research in their fields and be prominent intellectual voices.

- Unified teaching methods. Two teaching methods came to be the norm in American universities. First was the lecture. There was a large audience, little discussion, and an expert professor at the front. The second method would complement the first: the seminar. A professor would meet with a small group of advanced students to discuss and research a niche theme.

- Curriculum. Students in this era were being funneled into “majors” of specific study. Classical education was quite broad in the 1600s and 1700s. Studies were becoming more and more focused in modern American colleges, particularly to business and practical sciences.

- Modern facilities. The campus itself emerged as a large and complex institution, often with the university library being the central intellectual hub.

1910 — For the first time, colleges begin receiving more applications than they can accept, and therefore start implementing more rigid requirements. Before this time, colleges simply expanded the size of their classes. But, as going to college grew in popularity, the physical ability of a campus to handle students reached its apex. Colleges would either accept scores from an SAT-like exam, or work with partner high schools that had academic standards up to par.

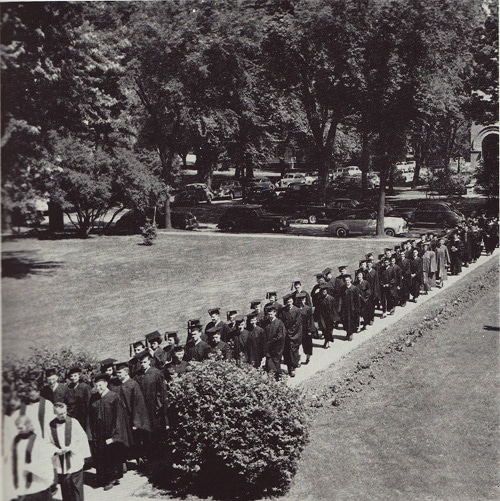

Student Army Training Corps, Syracuse University. The S.A.T.C was established at 528 colleges and universities across the nation. It effectively turned the college into a military post and every male student into an active duty soldier in the Army. The military got to train future officers and colleges got to maintain their enrollment numbers, rather than have all their students drafted and immediately sent off to fight.

1917 — Student Army Training Corp (a predecessor to the ROTC program) created by President Woodrow Wilson. This helped alleviate colleges’ fears about WWI’s impact on higher education. Colleges that participated in these on-campus training programs received generous repayment per student.

Spectators at a Syracuse football game in Archbold Stadium, late 1920s. The fun of watching collegiate sports became a big draw for college attendance and school loyalty.

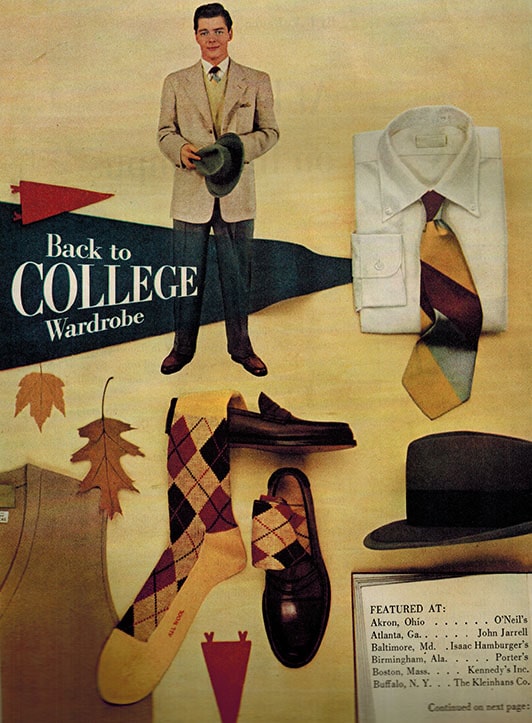

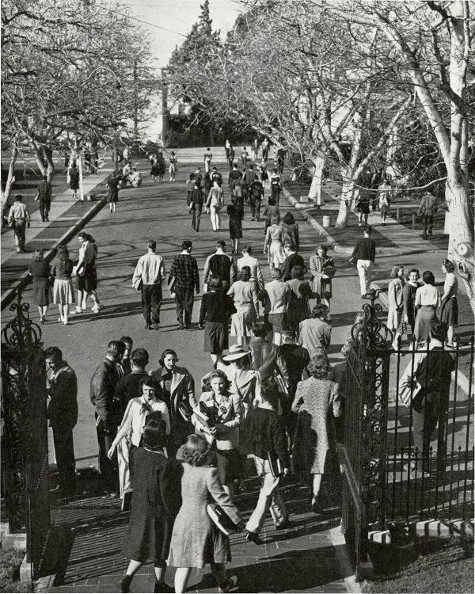

1920-1944 — The period between the world wars sees college attendance increase five-fold, from 250,000 to 1.3 million. The percentage of young Americans (age 17-20) enrolled in college jumped from 5% to 15% between 1917 and 1937. Part of this was because of another wave of donations coming in after WWI, so colleges had more money to pour into campus architecture, and especially large football and athletics facilities. College sports begin to take hold of America’s attention, and therefore the attention of young men and women as well.

In the 1920s, student life began to become more buttoned down.

1920 — The Roaring Twenties not only impacts American society on a grand scale, it begins to change the culture of American colleges as well. That riotous environment of large parties, bathtub gin, and gambling seeps into university life. This is a stark change from the gentlemen scholar environment that previously dominated college culture.

Mid-1920s — The uniquely American invention of the junior college becomes more and more popular. The idea is to truly give educational access to all teenagers. It functions as the first two years of work towards a bachelor’s degree. Over time, these schools also take on technical and vocational studies that prepare students for specific niche careers. By 1940, there are 150,000 students in junior colleges, and the majority receive their associate’s degree and then head to a traditional 4-year institution to finish out their bachelor’s.

1930s — Tuition prices at private schools begin to rapidly escalate. Between 1920 and 1940, the average tuition nearly doubled from $70 ($600 today) to $133 ($1,100 today). As this change came during the Great Depression (and Ivy League schools raised prices even higher), the prestigious colleges became even more out of reach for the general consumer, and all but a small percentage of American families are able to afford private schools. Meanwhile, state institutions remain fairly affordable, and some are still even free to in-state students.

1940s — While more Americans are going to college, there is still little specific value to the job market. Most occupations aren’t connected to academic credentials. If anything, simply being an alumnus of a certain school garnered more respect than specific skills learned.

A Timeline of Higher Education Post-1944

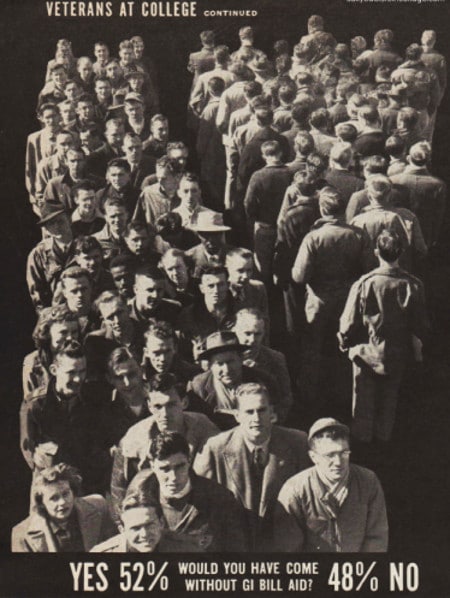

World War II dramatically changed higher education in America. While enrollment of course dipped a little bit during the war, the research facilities of many colleges became breeding grounds for military advancements. This is when the relationship between universities and the US government really became buddy-buddy. With the success of the war efforts, the attention given to colleges after WWII in terms of funding and grants and bills passed led to increases in enrollment that continue today.

After WWII, two million veterans took advantage of the GI Bill to go to college.

1944 — The 1944 GI Bill has provisions that allow free tuition for WWII vets in order to assimilate them back into a “normal” American life. It’s not actually expected to be very popular, but by 1950 over two million vets had taken advantage of the program. Since colleges knew they would be reimbursed directly by the government, they took to the powers of marketing to encourage vets to enroll. Ultimately, this meant that universities saw two- and three-fold increases in enrollment in just a few years’ time.

1957 — Russia’s launching of Sputnik provides another wave of research money to American universities, as the country felt it had to keep up with Russian technological advancements. Because of the success of the university’s role as a WWII research vessel, more and more money is being poured into schools to act as the government’s research arm. By 1963, there is $1.5 billion being received from the federal government by universities. For many schools, what they receive is anywhere from 20 to 80 percent of the total operating budget.

1960s — Because public schools get the majority of government funding, they are able to keep tuition prices low. Private schools, however, are having to continue to raise tuition prices in order to meet inflation and also provide a “luxury” product that would differentiate them from public institutions. In order for people to afford these schools, they come up with creative financial aid packages to get students in classrooms. They utilize a mix of grants, loans, and work-study opportunities. They tout small class sizes, study abroad opportunities, and niche class topics to stand apart from state schools. Since these schools are now setting themselves apart, they of course become even more prestigious to the public, and everyone wants in.

1965 — Community colleges (previously junior colleges) begin to see the genesis of their reputation as “inferior” schools. In the decades following WWII, 4-year institutions were seeing more applications than they could admit. The students who weren’t admitted would go to two years of community college, and then transfer to the 4-year school. Hence they became schools for less gifted students — you only went if you couldn’t get in somewhere more prestigious. In spite of this, students who transferred to 4-year schools after community college actually did better in their final two years than traditional students.

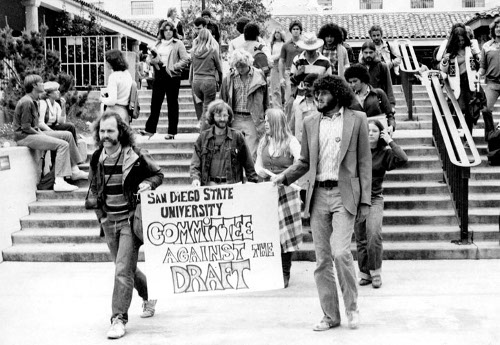

1972 — The Basic Educational Opportunities Grants (BEOG) program takes effect. Instead of the government subsidizing schools for student tuition, they’ll now give money directly to the students. Later, these grants are renamed Pell Grants. These were need-based grants given to full-time students, and those students were required to remain in good academic standing. The basic structure of Pell Grants remains nearly the same today, with the infamous FAFSA forms determining how much is given to each student.

1975 — For the first time in 24 years, college enrollment drops from the previous year. Due to student anti-war protests, the rise of independent research institutes, and various other factors, the government pulls a large amount of funding for universities. This leaves them in a bit of a crisis, as many of them had operating budgets that relied on this funding. The golden age of the American university is officially over, and schools must re-invent themselves to again gain favorable reputation. This led to two major changes: First, colleges began paying more attention to what students/parents wanted in terms of services and curriculum offered. Second, colleges began to welcome and even recruit part-time, transfer, and older, “non-traditional” students — groups who were previously just an afterthought.

1980 — As private universities continue their tuition hikes, and now state schools follow due to funding cuts, more than half of first-time college freshmen are enrolled at community colleges. And yet, Thelin writes that “the dominant image of the ‘real college experience’ remained indelibly linked to the four-year, fulltime residential tradition.”

Early 1980s — The discovery of the so-called Mt. Holyoke phenomenon: Charging higher tuition leads to a greater number of applicants, as well as academically higher quality applicants. To the college applicant (and their parents), price equals prestige. This phenomenon has not abated.

2008 — The recession hits, in large part due to the mortgage bubble. In the 80s and 90s, banks were giving mortgages at incredibly low interest rates to anyone that applied. There were hardly any checks in place to determine if people could actually pay their bills. As we’ll see in the next article, many economists are saying that student debt could be the next economic bubble. The recession means that more and more students need more and more financial aid in order to attend college.

2010 — Criticism begins to surface about the connection between a college degree and employment. While colleges tout the need for a degree to be employed, many graduating students — even in traditionally high placement fields like business and medicine — are not finding work. Thelin notes that “most colleges have succumbed to the misplaced belief that there is an indelible connection between academics and employment.”

2010 — Big-time college athletic programs take more and more heat, especially in terms of how much of the general operating budget they consume. Only 17 colleges have self-supporting athletic programs — that is, programs that are funded entirely through their own revenue. At most large schools, football budgets alone exceed what the athletic department brings in.

2010 — Student loan debt overtakes credit card debt in America for the first time. The average student who took out loans for school owes $25,000, largely to the U.S. government (they bought out most student loans during the recession). Meanwhile, the unemployment rate for 20-24-year-olds hovers at around 15%. This makes it difficult to get a job after college, and students are unable to pay back their debt. Because of this, almost half of college graduates aged 20-24 are back at home, living with their parents.

Today — Colleges are increasingly running into financial problems. Part of this can certainly be blamed on the athletics funding mentioned above. Other factors include overstaffed administrative offices, many of whom are overpaid (the average VP or dean — of which there are often a dozen or more per school — makes well over six figures, and up to seven figures), as well as colleges feeling the need to cater to prospective students in the form of luxurious dining halls, dormitories, fitness centers, and coffee shops. Commercialism has found its way to the university. Because of these increasing costs, tuition prices are rising at about three times the rate of inflation.

Concluding Thoughts

As you can see, the place of higher learning in American life underwent a slew of changes in the first decade or so of the twentieth century, and we’re seeing the same here in the first decade(s) of the twenty-first. A hundred years ago, colleges were experiencing a boom. Enrollments went up, campuses were re-done into spectacular complexes, even the mass media began to recognize the college student as the American norm for young adults (particularly young men). Much of that was due to the growing middle class of America. The late 1800s and early 1900s saw the American corporation take off. Mom and pop shops were no longer the norm, and more and more American men ended up in cubicles. While specific skills were still learned on the job, corporations wanted men who learned leadership, problem solving, and critical thinking at college.

Today, we’re seeing changes in the opposite direction. Schools themselves are seeing increasing financial problems, students (and their parents) are not able to pay for school, and the disconnect between a college education and gainful employment continues to grow. A hundred years ago, the college boom changed American culture. Will the 2008 recession and the growth of technical jobs and entrepreneurship in America change American culture and attitudes towards college again? Only time will tell. Next week, we’ll take a look at the pros and cons of attending a 4-year institution.

_____________________________________

Sources:

Creating the College Man by Daniel Clark

A History of American Higher Education by John Thelin