Are you intentionally making mistakes at work to make yourself look incompetent?

Are you purposely sabotaging your presentations?

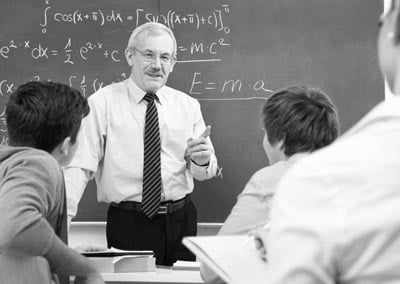

Are you setting yourself up for failure as an instructor?

Hopefully, the answer is no.

Yet the vast majority of men I see who want to be influential fail to master the three tips I’ll share today. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Men spend a lot of time, money, and effort learning to be more persuasive speakers and negotiators. And for good reason — mastering these skills can reap huge returns when it comes to business and personal success.

But what if there were something you could do that would dramatically increase your persuasiveness without any extra effort or training on your part?

Would you take advantage of it?

If the answer is yes, it’s time to start thinking more about your personal appearance and how it relates to the art of persuasion and influence.

Attractiveness and Persuasion

We like to think that persuasion is a matter of good arguments and compelling rhetoric — in part because we don’t want to believe that we can be swayed by anything less.

The research says otherwise.

There have been a number of studies in the last fifty years that demonstrate people’s tendency to be more persuaded by attractive speakers than by unattractive ones.

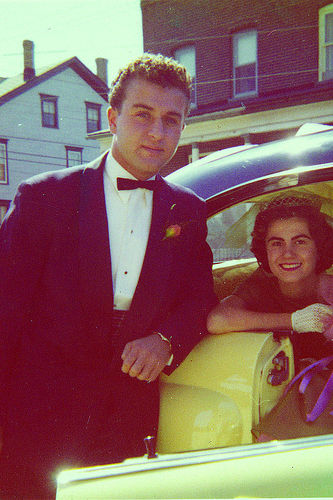

In 1979, Shelly Chaiken published a paper on her study of instructors in academic settings. She found that instructors rated as “attractive” by their students could generate significantly higher levels of agreement from their audience than ones rated as “unattractive.” Even more impressively, the study also demonstrated that students actually performed better when they had an instructor they found attractive.

Why Attractiveness Affects Influence

It’s a little disheartening to think that just being handsome can make people under your leadership perform better, or make audiences more likely to agree with your point of view.

Worth bearing in mind is that it’s not a one-way street. Attractive individuals tend, on the whole, to have an easier time in social situations than unattractive ones. That, in turn, encourages them to be more outgoing and social, which gives them more practice with their interactive skills.

But with that said, there’s also an effect on the viewer’s brain when a person is particularly attractive. Our brains are big into shortcuts. Give them a chance and they’ll save mental energy by categorizing people into simple, all-or-nothing terms like “good” and “bad,” or in this case, “attractive” and “unattractive.”

That gives us a tendency to take a broad, generalized assumption about a person, such as “he looks good,” and then ascribe that quality to specific judgments as well, such as “he’s probably a good teacher,” or “he must be a good father.”

This is called the “halo effect.” It was first studied in the 1920s by a researcher named Edward Thorndike, who had noticed that in military evaluations, officers who were ranked highly in some qualities were ranked highly in other, unrelated categories as well. Similarly, officers with low rankings in some categories usually had low rankings in others.

What does a squared-away uniform say about a Marine?

Objectively, the results didn’t make sense. Unrelated qualities like physical fitness and mental attentiveness should, in theory, be randomly distributed. You might get one or two high performers very good at everything they do, and one or two washouts who aren’t good at anything, but in general people should be good at some things and not at others.

What Thorndike found, however, was that one strong positive impression — an officer’s physique, say, or his attention to neatness and punctuality — was enough to generate an overall “good feeling” that spilled over into the rest of the evaluation. Once the person filling out the evaluation noticed something good about an individual, he assumed that they were good at other things too. The result was true for negative impressions as well.

Studies have shown, with remarkable consistency, that the halo effect is real and has a statistically significant effect on people’s success, in everything ranging from education to politics to courtroom defenses (one study showed that attractive people received much more lenient sentences than unattractive ones, even when convicted of the exact same crime).

This effect comes into play when you’re trying to persuade, in any setting or situation. The more positive people’s first visual impression of you is, the more positive traits they’ll associate with everything you say. A 1975 study found that clothing had more impact on first impressions in social settings than the person wearing the clothing — powerful stuff when you’re getting up in front of an audience!

How to Dress to Persuade

It should be obvious, then, that anyone who needs to persuade — for a job, a cause, or anything else — wants to look as “good” as possible.

But what is “good,” in personal appearance?

1. Be Free of Imperfections

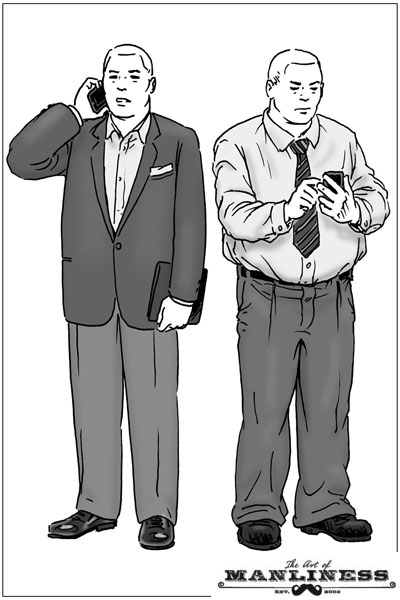

Can you spot the imperfections that different clothing exaggerates or masks on the same man?

To persuade, be meticulous.

Be meticulous about your hair, be meticulous about your shoes, be meticulous about your clothes. Everything counts.

Your goal when you prepare for a persuasive speech or sales pitch is to eliminate imperfections.

A tuft of hair out of place or a scuff on your shoes may not seem like much, and realistically, most people won’t consciously notice something minor like that, but their subconscious mind is still picking up the visual signal of asymmetry, and that tells the back of their brain that something isn’t quite right. The result is a vague, indefinable and off-putting sensation that the viewer won’t even be aware of — but that will be coloring his or her judgment of you.

Our brains evolved to use basic bilateral symmetry as a sign of good health and development, so they easily pick up on anything that deviates from that pattern. Always strive for a symmetrical look — or, when you break it, for a firm and deliberate asymmetry. A bright splash of color on one breast from a pocket square is fine; a faint stain on one lapel is not.

Remember that humans can generally only pay attention to one thing at a time. Our brains and our eyes are good at focusing, but bad at interpreting multiple stimuli at once. If you give people something out of place to focus on, they’re going to zero in on it. Thinking about how your tie doesn’t go well with your pants takes up the brain space they should be using to consider your message.

When you think about it, even things that we recognize as major gaffes aren’t much more than small details done wrong. Showing up at a presentation with your fly unzipped is, in practical terms, a flaw in maybe 1-2% of your total appearance. The rest of your outfit looks just fine! But we all know how big of a difference that one little zipper out of place is — it’s a deal breaker, guaranteed.

Things that logically have nothing to do with your intelligence or with the value of the message can still leave people thinking that you’re unconvincing. So take the time you need to get everything just right.

Aim for perfection. Go for the extra slow shave, the just-right-for-you hair product, the shoeshine in the airport. They end up mattering.

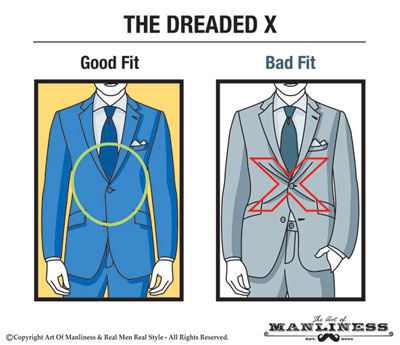

2. Be Well-Fitted

The neat, crisp outline of well-fitted clothing serves the same purpose as painstaking attention to detail — it removes subtle asymmetries from your overall image.

You’re never going to look as attractive as you can if you have loose folds of cloth sagging off your body. A too-tight fit is just as bad, since it wrinkles and bunches when you move, so aim for a fit that’s close to the skin, but not restrictive. Click here for a refresher on how a suit should fit.

Pay attention to your proportions here as well, especially if you’re outside the average build for a man. It’s easy for details like the pockets on shirts and jackets or the length of cuffs to get pulled far enough away from “normal” that the look is off-putting if you’re unusually large or small.

Part of this is avoiding off-putting imperfections. Another part is evolutionary — human brains like straight-limbed, well-proportioned bodies. They look like strong leaders and capable providers. When you look like that, you become the sort of person that other humans instinctively want to have in their group. The urge to fit in with you — and to agree with you — gets stronger.

Having clothing adjusted to flatter your body as much as possible encourages that eagerness to agree with you. If your posture and your outline has already convinced the audience that you’d be a good guy to keep around, you’re halfway to convincing them of anything else as well.

A little tailoring goes a long way. Plan on having the majority of your clothes adjusted by a tailor who knows you well. The differences are subtle, but the cumulative effect is impressive.

3. Be Dressed Up, Not Dressed Down

Finding the exact level of formality can be tricky, especially if you’re speaking in a casual or non-traditional setting.

More than one politician has gotten himself in trouble by showing up at a soup kitchen or a disaster shelter wearing a tailored suit and an expensive silk tie.

In general, when attempting to persuade, you want to err on the side of looking like you dressed up for the occasion, not dressed down. Lean toward the more formal end of what your audience will be wearing (but not too much beyond that).

There’s a very simple reason for this: you’re trying to influence, and therefore your clothes should be the clothes of an influential man. The halo effect will kick in for you once again, making people much more receptive to your words and ideas.

For most of the Western world, that usually means a suit or blazer-style jacket. The V-shaped chest opening and squared shoulders speak to our subconscious minds of power and influence — and as an added bonus, they flatter the male physiology too, making you look more dominant.

Don’t be afraid to look a little more dressed up than the people around you. That’s your way of showing them respect. Subconsciously, they’ll assume that your ideas are important too.

There’s a practical element here as well: it’s much easier to correct being “overdressed” than under-dressed. If you show up somewhere in a tie and jacket and you realize that absolutely no one else there is wearing anything nicer than a casual collared shirt, it’s not that hard to slip off your jacket and tie, roll up your sleeves, and fit right in.

If you show up in blue jeans and a work shirt and find everyone else wearing suits, that’s a lot harder to correct for. So err on the side of dressing up more than everyone else, and shed accents or layers as needed to bring it back down if you really feel out of place.

Be Attractive. Be Persuasive.

If it sounds irrational to you that something so unrelated to your other merits can have such a powerful effect, don’t worry — you’re not alone.

The halo effect is just one of many seemingly irrational ways that the human brain processes external stimuli. But that doesn’t make it any less true.

Most people, if they really think about it, can recognize at least a few times when they’ve let a public figure’s appearance or charm affect their perception of other, unrelated issues.

It’s why Hollywood celebrities so often get away with extreme behaviors that would be off-putting in others — we already have a perception of them as larger-than-life characters (since that’s how we see them in their on-screen roles), so it seems “okay” for them to behave that way on the streets of Los Angeles as well.

So yes, it can be hard to believe that something as simple as wearing nice clothing can actively improve your powers of persuasion. But have a little faith in the science and in your own understanding of human nature.

It’s not a magic charm. Just having a good suit isn’t going to make people agree with everything you say. For one thing, there are a lot of other guys out there in good suits already, so you have lots of competition for people’s attention!

But you can create a positive first impression by being neat, by having the attractive outline that well-fitted clothing brings, and by looking just a little more dressed-up than the men around you. That edge might just be enough to tip the scales in your favor and get you the job, the sale, the votes — whatever it is you need from other people.

There are limits to the effect, certainly. Even a very well-dressed man isn’t going to be listened to if he’s shouting about the aliens in his head. But a well-dressed man speaking calmly about reasonable-sounding ideas is much more likely to be believed than the same man giving the same speech in a sloppy outfit.

Watch a Video Summary of This Post

Written By:

Antonio Centeno

Click Here For My Free Book – The Seven Deadly Sins Of Style