Editor’s Note: This a guest post from Ian Walker.

A Thing I Didn’t Do

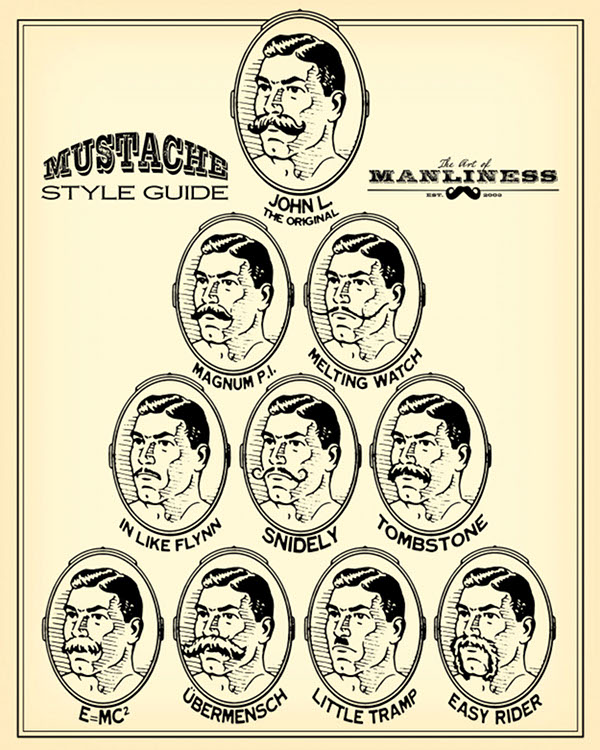

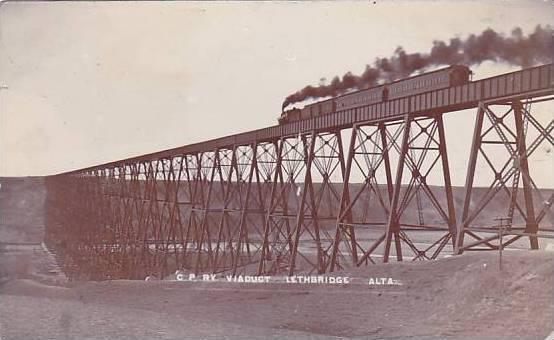

In Lethbridge, Alberta, where I went to university and lived for five years, there is a very large, very long, and very high train bridge. It stretches across a giant valley that has been carved away by the Oldman River. It’s a beautiful area in the heart of the city. The river is surrounded by rolling hills, and the university sits atop them like a boat carried by the waves of the sea. The valley is so deep and just wide enough, that were a train to go down into it, even gradually, it would never come back out. So in an effort to prevent trains from being swallowed in the belly of Lethbridge, early workers built the bridge across the valley. Trains don’t have to dip or climb: they just go straight across. Over 300 feet tall and 1.6 kilometers long (just under one mile), the High Level Bridge, as it’s called, is the largest of its kind. It was completed in 1909 by manly men who probably all had moustaches or beards, wore suspenders or flannel suits, didn’t have safety equipment, and had never driven a car. And I don’t understand how they did it. The bridge has always fascinated me. And from all angles – from the highways on both sides, underneath it, and even on top of it; whenever I really look at it, I’m in awe. It’s the symbol of the city and its main attraction. People have their picture taken by it, it’s on postcards, and a Google image search of “Lethbridge” fills the screen with mostly pictures of the bridge. It is Lethbridge, and in a sense, my whole experience living there revolved around the bridge.

Early on in my time in Lethbridge, I mentioned in conversation how fascinated I was by the bridge and how I would love to know how it was built. The person I was talking with happened to have recently visited the local museum, where a video is regularly shown that documents the construction of the bridge. Perfect. I was talking to the right person at the right time and my problem was solved. A gift from the universe. But I spit in the universe’s face. Despite my deep interest in the topic, the proximity of the museum, the low admission fee, my flexible student schedule, and the fact that the experience would provide me exactly what I was looking for, I never went. The whole time I lived there, I never went.

I’ve thought about this many times. Why didn’t I ever go? Why wouldn’t I do something so easy – something I wanted to do?

Theory of Doing Things

Bored out of his mind in Mundare, Alberta (population 855), Albert Bandura decided to grow up to become a world-famous psychologist. And what Albert Bandura decides to do, Albert Bandura does. Now among the most cited psychologists, and clearly a doer of things, Bandura is the authority on getting things done. His Social Cognitive Theory revolves around the concept of self-efficacy. According to Bandura, self-efficacy is, “the belief in one’s capabilities to organize and execute the courses of action required to manage prospective situations.” In other words, self-efficacy is your belief in your own ability to do the things you want to do.

People with high levels of self-efficacy:

- See problems as challenges to overcome, or tasks to be mastered. Even completing small tasks is a source of satisfaction.

- Develop deep interests and are active participants in various activities. Interests grow and develop and the world seems big.

- Form a strong sense of commitment to their interests. They don’t go half-way, or start projects and give up quickly.

- Recover quickly from setbacks and disappointments.

Whereas people with low levels of self-efficacy:

- Avoid challenges (or inconveniences) – big or small (or even very small).

- Believe difficult things are beyond their abilities. They see other people doing things and assume the position of observer, not participant.

- Focus on their personal failings. They don’t give themselves credit.

- Lose confidence easily and quickly, giving up on new things when they’re difficult, uncomfortable, or just different.

I believe the answer to why I didn’t do an easy, and probably enjoyable, thing, lies in this concept of self-efficacy.

But what about doing hard things?

A Thing I Did

The bed was a little wider than my body and not quite as long. It sunk in the middle so it was more like a hammock or a trampoline than a bed. And the blanket was thick and stiff, suspended over the bed like a tarp on a canoe. I had been cold and lost and alone, but found my way to my room to regroup and recuperate. The room smelled like sulfur and I didn’t know what time it was. I didn’t know what time I arrived in Iceland, but found that it was earlier than stores opened. With no coat, no watch, no friends, no map, and no way to get any of those things, finding my room was a victory. Being alone in a strange place hit me hard, so I crumpled myself into my little nook and went to sleep. The nap was a success, and I soon turned things around and had a wonderful three days by myself in Iceland.

I had always wanted to go to Iceland. So I went. I spent three days alone there, finding my way around, doing activities, learning some of the culture, navigating the lunar landscape (a tour I went on informed me that NASA took their astronauts to Iceland to get a feel for what it would be like on the moon), getting goods and services without knowing the language, adjusting to the time change and the never-setting sun, exploring and going on excursions, and overcoming low spirits to relax and enjoy. By all accounts, doing all that was much harder than driving down the street to go to a museum. Both were things I wanted to do; I did the hard one and never got around to the easy one. Why? It would be easy to say that going to Iceland is more interesting than going to the museum in Lethbridge, but I believe my fascination with that bridge was equal to my desire to see Iceland. Self-efficacy can provide some answers.

Bandura’s Theory of Doing Things, Again

According to Bandura, self-efficacy is deep-rooted. It develops in four main ways:

- Social modeling. Seeing other people succeed raises our belief that we too can succeed. This is especially true when the person is within our sphere of influence. We may think things like, “If that regular schmo can do it, I can too.” But it can also go the other way: “If that awesome dude can’t do it, why should I be able to?”

- Social persuasion. Encouragement from others makes it easier to do things, and discouragement makes it harder. This can be obvious or subtle. Not getting the encouragement we’re hoping for, even with no direct discouragement, can severely weaken our ability to do things. This shows how fragile self-efficacy can be when not tended to.

- Mastery experiences. Bandura says this is the most effective way to develop self-efficacy. Succeeding makes further success easier to attain. But it almost seems stronger going the other way. One failure, no matter how minor, can be a huge blow. Again, self-efficacy is a fragile thing when left on its own.

- Psychological responses. Our moods, feelings, physical reactions, stress levels, and other states of mind can affect our levels of self-efficacy. But Bandura notes, “It is not the sheer intensity of emotional and physical reactions that is important, but rather how they are perceived and interpreted.” We can take charge by being aware of them and how they affect our self-efficacy.

But why didn’t I go to the museum?

I mentioned above that people with high levels of self-efficacy have deep interests, form deep commitments, recover quickly from setbacks, and take satisfaction from completing tasks and overcoming challenges. People with low levels lose interest and give up easily, remain uninvolved, focus on their failings, and avoid challenges and tasks. So according to that definition, I have both high levels and low levels of self-efficacy: I make deep commitments, have deep interests, and overcome challenges, but also give up easily, and avoid tasks.

My own experience tells me that we can have different levels of self-efficacy in different areas, or for different types of tasks. It seems that I have higher self-efficacy in doing more involved things, and low self-efficacy when it comes to smaller tasks. We could categorize tasks in many ways: big, small, medium, long-term, short-term, involved, straightforward, complex, simple, and so on. And I believe if we plotted our levels of self-efficacy on a graph, with self-efficacy on the vertical axis and categories of tasks on the horizontal axis, and connected the dots, most people would have a mountain range. It would be really high in some areas, really low in others, and everything in between. But just as seeing ourselves succeed makes further success more likely, looking at our high levels in one area makes it easier to increase those levels in another. Remembering that I can do big things makes it easier to do small things. And if it’s the other way for you – small tasks are easier but you avoid big things – remember that big things are just a lot of small things piled on top of each other.

So how do we increase our levels of self-efficacy?

The first step is to know yourself. What types of tasks give you difficulty? No one finds everything difficult, but everyone probably struggles with something. Examine your life. Think small for now. Imagine yourself going through a normal day. What do you put off for later? What do you get done right away? Here’s an example from my own life. A typical Ian day:

The alarm goes off at 7:00 AM, and I hit the snooze button and get up at 7:10, or sometimes I hit it again and get up at 7:20. If I get up at 7:20 I have to skip breakfast and pick something up at the cafeteria on my way to my office at the college. This late riser’s breakfast is usually a giant muffin and 2% milk. The muffin is delicious but too sweet and it usually gives me the jitters, and by lunchtime I don’t feel like eating. It’s safe to say two snoozes is too many.

I head to the shower where I use a giant bottle of shampoo I bought from the dollar store. I didn’t know there’s a difference between shampoos, because I am a man. Now I know there is a difference. The one I use seems to be made of barely more than water, and I guess my hair feels a bit cleaner after using it. I should replace it.

I only shave on days my beard feels itchy, even though I don’t look good after two or three days.

I get dressed and if there’s time, eat breakfast. If I can get up at 7:00, I have time for eggs and toast. But I don’t usually. So it’s just toast. Not bad, but the protein from the eggs makes me feel virile and supercharged, and I miss it when I don’t have it.

I drive to work in my car with the burnt out signal light and overused oil and park far from the office because I enjoy the walk. I get to my office and sign on to work email, which is usually empty, and personal email, which is usually full. I keep my phone on my desk and respond to texts and emails as they arrive. I have intermittent periods of focus throughout the day. I wonder if I have Attention Deficit Disorder, or if I’m just a modern human. The project I’m working on at work is very interesting, and I have innovative and exciting ideas about it, but only manage to focus on it in short spurts. When a thought comes to mind, I act on it – no matter how unimportant or unrelated it is. The internet on my computer is very fast, and I can find answers to my stupid questions very quickly. Is Channing Tatum in both G.I. Joe movies? BAM! Imdb. I wonder how some people rack up so many frequent flyer miles. BAM! Travel blogs everywhere. Did Stephanie Meyer think of the idea for The Host before or after Twilight? BAM! Um…I don’t know where I’d find that one. I’ve never actually wondered that, but you get the idea. Each of these detours lead to more and sometimes I’ll go for a while before realizing I’m off-track. Then I’ll get back on track, get on a roll, and make major progress on my project. And then it happens again. Whenever possible I do my work off of the computer to avoid this problem.

I come home for lunch because I enjoy seeing my family, and the food there is freer and healthier than what I’d get at work.

After work I make a list of things I want to get done that evening. An old note in front of me now has two tasks related to the business I’m starting, and one administrative task. I did the two business related ones, and still haven’t done the other.

I spend time with my family. Now that the weather is nice, we try to do something outside and avoid watching tv or movies. We’ve gone on picnics, walks, played at the park, threw the ball for the dog, and other things. My family is the most important part of my life, and I make it a priority to spend time with them, even when I have other things to do.

We read before bed because we both enjoy it. We do it even when we get too bed late.

My Self-Efficacy Strengths and Weaknesses

Strengths:

I’ll start here because the weaknesses are more obvious.

- I’m good at working on big things and things that have long-term impact. This includes the project at work.

- When I set priorities, I stick with them. Time with my family is non-negotiable. I think reading is one of the better ways to use time, so I make sure to do it regularly. I’m conscious of my health. That doesn’t mean I always make the right choice, but choosing to eat at home is a good choice that I make regularly.

Weaknesses:

- I’m bad at small things.

- I snooze.

- I use gross shampoo.

- I sacrifice a good breakfast.

- I shave as little as possible.

- I ignore problems with the car because I can’t be bothered to take the time to do the minor repairs.

- I get easily distracted at work.

- I only do items on my list that will bring long-term benefits.

- And so on.

It’s a bit humbling to look at how much I suck. But it’s a good start to figuring out how to suck less.

I encourage you to do the same exercise. Think about your day, and print off this page and fill in these blanks (or write your answers on another piece of paper at least – but actually do it, fellow Manly Doer of Things).

Strengths:

List 5 things you got done today.

_____

_____

_____

_____

Weaknesses:

List 5 things you should have done today, but didn’t do.

_____

_____

_____

_____

_____

The weaknesses should be easier to spot. But focus on your strengths. When you understand your strengths – the areas where your self-efficacy is high – you can understand how to improve your weaknesses. Let’s look at me again.

I’m good at doing long-term or complex things, and avoid doing smaller and simpler things. It’s much easier to buy a bottle of shampoo than it is to build a business. It might be easy to say I’m more excited about building a business than I am about getting shampoo. And that might be true. But when I do finally get around to replacing the shampoo, I’ll feel very satisfied and look forward to using it. Completing any task always brings some level of satisfaction. Often the satisfaction level is the same from completing small tasks as it is from completing big ones. But I avoid the smaller tasks.

When I look closely, I see how little this makes sense. Any long-term, big, complex, complicated, multi-faceted, in-depth task is just a bunch of small tasks in a row. And there are no exceptions. Completing each of these small tasks is no more satisfying than buying a new bottle of shampoo. Even just keeping that in mind helps make any type of small task more manageable.

Or we could look at it the other way around.

If I’m motivated by long-term benefits, it helps to realize that each small task has a long term benefit. And again, there are no exceptions. They may not be earth-changing benefits, but they are benefits. Fixing my car will save me money on more serious repairs later. New shampoo will keep my hair healthier, because there’s no way the slime I use now does it any good. Getting up one snooze earlier means better breakfast and better health.

But maybe your self-assessment had the opposite results.

Maybe you’re good at getting every item on your list done, but you have big dreams, goals, plans, or tasks that you don’t bother with.

I think you already know what to do. But to illustrate, here’s a story. Anne Lamott relates the story behind the title of her guide to writing, Bird by Bird:

“Thirty years ago my older brother, who was ten years old at the time, was trying to get a report on birds written that he’d had three months to write. It was due the next day. We were out at our family cabin in Bolinas, and he was at the kitchen table close to tears, surrounded by binder paper and pencils and unopened books on birds, immobilized by the hugeness of the task ahead. Then my father sat down beside him, put his arm around my brother’s shoulder, and said, ‘Bird by bird, buddy. Just take it bird by bird.'”

Remember, big tasks are just a bunch of little tasks piled on top of each other. Use what you know about getting small things done. Start small, and take it task by task.

Understanding is a giant step to overcoming. Thinking like Bad-Ass Bandura (as his friends probably called him) — consciously tending to your self-efficacy and realizing it is a driving force behind your actions or inactions — will open up your whole life and jump-start your progress as a man. Few things are manlier or more satisfying than doing exactly what you set out to do.

_____________________

Ian Walker is a normal guy with a good life who wants to enjoy it even more. He writes on his site, “Doing Things” (www.iantwalker.com): a place for people who want to do things but haven’t done them, or who have done things and learned what it takes to do them. Stop by and say hello.