“The Majesty of Strength”

From Royal Manhood, 1899

By James Isaac Vance

“O, east is east and west is west and never twain shall meet

Till earth and sky stand presently at God’s great judgment seat;

But there is neither east nor west, border, nor breed, nor birth.

When two strong men stand face to face, though they come from the ends of the earth!” —Kipling

Strength is the glory of manhood. Beauty is not, for beauty is only to be displayed. Culture is not, for culture is chiefly for self-glorification. Fluency is not; a parrot may be fluent. Agreeability is not; a fool may make himself agreeable. Not smoothness, nor plausibility; not softness nor polish, but strength is the glory of manhood. Manhood and strength are synonymous.

Where in all the sweep of freaks and failures, of mawkish sentiments and senseless blathery, can there be found an object to excite deeper disgust than one of these thin, vapid, affected, driveling little doodles dressed up in men’s clothes, but without a thimbleful of brains in his pate or an ounce of manhood in his anatomy? He is worse than weak—he is a weaklet. What can he do? He can squeak with his little voice, strut with his unathletic members and gabble diluted twaddle. He can sigh and pose and outclass the monkey in apish arts. This shitepoke specimen of man tells us that he is tired of life, but of work he can never grow tired, for to that he is a stranger. He affects to look with great disdain on common toil and common people, but the world is grateful that such a specimen of the genus homo is himself uncommon.

Many a man has failed in life for no other reason save that he was weak. He had a good heart, but he was weak. He was popular, generous, gentlemanly, but weak. His opportunities were fine, his capital ample, his future inspiring, but he was weak and went to nothing. The ideal Christian has something to him besides syllabub. He must do more than sing Psalms, and testify in the meeting. He is not at his best when the world slaps him in the face, knocks him down, and stamps him. He must be humble, but also strong. He must practice self-denial, but should also possess self-respect. He is taught to forgive his enemies, but also to be angry and sin not. A lovely priest in Paris had incurred the enmity of the sectarians by his liberality. One day a bigot, who was also a bully, met him on the street and dealt him a rousing blow on the cheek. Quietly the lovely priest turned, saying: “My Master teaches me when thus struck to turn the other cheek also.” Delivering a still heavier blow on that cheek, the bully said: “And what does your master tell you now?” To this the lovely priest replied, as he laid aside his cloak, “The authorities are divided, but the weight of authority is in favor of the view which I now adopt as I proceed to give you the worst thrashing of your life.” It is not likely that at the final reckoning, the lovely priest will find much against him for that day’s work.

Strength calls for self-restraint and self-control, but also for self-respect and self-assertion.

If one expects to amount to anything in life, he must be strong. Barriers are to be surmounted, discouragements silenced, temptations resisted, and for all this there is needed a manhood invincible and self-reliant, strong.

The voice of our highest destiny speaks. It points the way to the summit, achievement of life’s best ambition. It voices our deepest and constant need. It says: “Be strong.”

What is strength?

It is the absence of excuse-making. “If I had that fellow’s chance, if my circumstances were different, if my capital were larger”—out upon all such unmanly whimpering. The music of strength is not set in the key of whines. We must accept life as it is and make the best of it. Whenever a speaker begins with an apology, you may know his audience is to feed on chaff. Strength strikes the word “excuse” from its vocabulary.

“‘If I were a man,’ said the restless lad,

‘I’d never give up and be still and sad.

Were my name but known in the lists of life

I’d never say “die” till I’d won the strife.

But who will challenge the steel of youth,

Though his heart be brave and his motto “truth?”

There’s work to be done in this life’s short span,

But alack-a-day! I am not a man.’“‘If I were a boy,’ said the toiler gray,

‘I’d fashion my lot in a better way.

I’d hope and labor both day and night

And make ambition my beacon light.

I’d bend the oar, nor drift nor dream

Were my bark but launched upon youth’s bright stream,

Till I reach the haven of peace and joy—

But, alack-a-day! I am not a boy.'”

Strength never comes down to such sentimental doggerel as this. It may fail, but it will bear defeat with fortitude.

Strength is industry. Hard work is only another name for genius. Weakness is often only another name for laziness. It may call itself indisposition, leisure, or some other highsounding platitude, but that doesn’t change the sluggish inside. A lazy man is a butt of ridicule for all creation. He may have a bank account, but in the world of brawn and brain he is a dummy. The men who have achieved conspicuous success in medicine, law, literature, art, trade, have all been tireless workers. Strength is self-reliance.

Henry Ward Beecher used to tell this story of how he was taught when a boy to depend on himself.

“I was sent to the blackboard, and went, uncertain, full of whimpering.

“‘That lesson must be learned,’ said my teacher in a quiet tone, but with terrible intensity. All explanations and excuses he trod under foot with utter scornfulness. ‘I want that problem; I don’t want any reason why you haven’t it,’ he would say.

”I did study two hours.’

“‘That’s nothing to me; I want the lesson. You need not study it at all, or you may study it ten hours, just to suit yourself. I want the lesson.’

“It was tough for a green boy, but it seasoned me. In less than a month, I had the most intense sense of intellectual independence and courage to defend my recitations.

“One day his cold, calm voice fell upon me in the midst of a demonstration, ‘No.’

“I hesitated, and then went back to the beginning; and, on reaching the same point again, ‘No!’ uttered in atone of conviction, barred my progress.

“‘The next!’ And I sat down in red confusion.

“He, too, was stopped with ‘No!’ but went right on, finished, and, as he sat down, was rewarded with ‘Very well.’

“‘Why,’ whimpered I, ‘I recited it just as he did, and you said “No!'”

“‘Why didn’t you say “Yes,” and stick to it? It is not enough to know your lesson; you must know that you know it. You have learned nothing until you are sure. If all the world says “No,” your business is to say “Yes,” and prove it.'”

One must be sure of himself. He must have self-poise. This is not conceit. Conceit is all wind, and the point of a cambric needle can puncture it to death. Self-reliance is the absence of timidity. It is alertness and forethought. It is preparation and decision.

Strength is reliable as well as self-reliant. It may be counted on when the fight waxes hot. One must command the confidence of others as well as his own. The wretched thing about so many who fail is that they cannot be depended on. They are goody-goody, but not reliable. It is a waste of time to dread the disagreeable. It must be faced promptly and duty manfully met.

There must be moral as well as physical strength. There must be the courage that stands to its convictions, whatever people may think or say. The hardest mouth to face is not the cannon’s. It is rather that from whose throat comes the insistent roar of the fickle populace. The majestic strength of royal manhood treats this as an elephant does a fly.

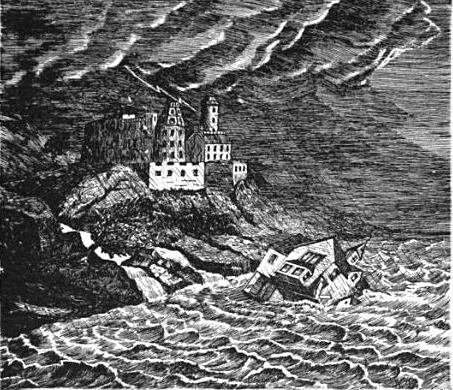

There are temptations to be resisted. Nothing short of moral strength suffices for this. Innumerable iniquities solicit tolerance or indulgence, and if yielded to, they will damn here as well as hereafter. A young man came to Nashville a church member and with a clean moral record behind him. He had unusual advantages for success in a noble profession. But he began going to the devil for no other reason than he was weak. His companions were the kind that make the public suspicious, and the people who associate with them impure and dishonest. Two years were enough to bring his prospects in life to zero. He will whine about his poor chances, and the little encouragement given by friends. The truth is he killed his chances with moral cowardice. Strength means moral courage, and ability to stand against ridicule and popular clamor. Strength is not like the willow that bends low to every breeze, but rather like the oak that stands stiff in the tempest, or like the granite cliff against which the mad sea dashes itself to pieces, or like the mountains that lift their calm faces toward the silent stars defiant of all the bluff of storm.

This is what it means to be strong, and before such a life the world makes way. Such manhood is in command. The world grows roomy now. In state and church, in public and private life, in work for men and work for God, the call is for men of strength.

Strong in purpose and strong in action; strong within and strong without; strong against foes that are seen and strong against foes that are unseen; all the way up and all the way down, all the way around and all the way through; first, last and always—strong! It needs neither title nor crown to argue the imperial majesty of such manhood.

Tags: Manvotionals