“You can do anything you put your mind to!”

“The sky’s the limit!”

“You’re the best!”

“Follow your dreams!”

Did you hear these kinds of things growing up? Your parents sure meant well. They really felt like you were the most special creature to arrive on planet earth – a beautiful boy full of limitless possibilities. You could do anything in the world!

But now that that boy is grown up and in his twenties, you might find that such encouragement has become more paralyzing than motivating. If your possibilities really are endless, how will you ever decide which path to take and what to do with your life?

Meg Jay is a clinical psychologist who specializes in counseling young patients who are struggling with navigating their twenties. One of the case studies she talks about in her fantastic book, The Defining Decade (we have and will be referencing it a lot here on the blog – it’s really a must-read), focuses on “Ian,” who can’t decide what to do with his life. Should he pursue something in graphic design, go to law school (which would please his parents), learn Arabic and do some kind of foreign service work, or maybe postpone the decision altogether with a trip through Asia? He feels like he’s drowning in a vast ocean of choices and doesn’t have any idea which direction to head. Jay writes:

“He couldn’t see land in any direction, so he didn’t know which way to go. He felt overwhelmed by the prospect that he could swim anywhere or do anything. He was equally paralyzed by the fact that he didn’t know which of the anythings would work out. Tired and hopeless at age twenty-five, he said he was treading water to stay alive.”

The Alluring Myth of a Limitless Future

As we all intrinsically know (and for reasons we’ll discuss more below), nobody’s future is in fact “limitless.” But holding onto the feeling of endless possibilities, instead of going after a few of them, is very alluring — even if doing so makes us anxious or restless. Here’s why:

It feels freeing. People love having as many choices as possible (even if an overload of them can make us unhappy). Believing that every avenue is still open to you is both comforting and liberating. We love the sense of the unknown and the intoxication of vast possibilities.

For this reason, we may hesitate to choose one door, as it can feel like doing so closes a bunch of other ones. Getting an MBA and going into business likely means you won’t be an orthopedic surgeon; we want to hold to the belief we could do either one, yet we choose neither. As Ian put it, “claiming something felt like losing everything else.” Plus, in contrast to the noncommittal task of peering in each direction from the middle of an intersection, picking a single road to start traveling down can feel boring and constraining – as well as a lot more work. Once you choose a path to take, that decision comes with necessary next steps and responsibilities. It’s much easier to sit on the curb and watch the world go by than to hustle and make something of yourself.

You have incredibly high expectations. Because many in Generation Y (I’m right on the tail end of it myself) were raised to feel as though we were (and are) very special, we often say we don’t want to settle for an “ordinary” life. We want our lives to be different than our parents’ were in some way — to be extraordinary. People feel very convicted about this, but if you ask them what having an extraordinary life means, they’re usually not sure. They’re likely to say something about not wanting a regular 9-5 office job and wanting to do something they love, but even here they’re vague on what this might actually look like. They know what they don’t want, but aren’t sure of what they do. They figure they will simply know it when they see it, and so keep their options open in the hope that the path to an “extraordinary” life will somehow reveal itself.

You don’t know how to get started. Sometimes those who say they don’t know what to do with their life in fact really do know. What they don’t know is how to go after that dream, so it feels better to tell themselves, and others, that they’re still trying to figure things out. As Jay puts it, not knowing what to do with your life brings great uncertainty, but “the more terrifying uncertainty is wanting something but not knowing how to get it.”

If you don’t start, you can’t fail. Even if you do have an idea of how to get started on building the life you want, you might be scared of trying and then failing. If you keep all your choices in the realm of mere possibilities, you don’t have to risk finding out you don’t have what it takes.

You’re afraid of making the wrong choice. This is a huge reason people hold onto the myth of a limitless future. What if you choose one of the possibilities you’ve been endlessly examining and then you don’t like it? What if you get stuck doing something “ordinary” – something that doesn’t fit your idea of what your life was supposed to be like or what you were really meant to do?

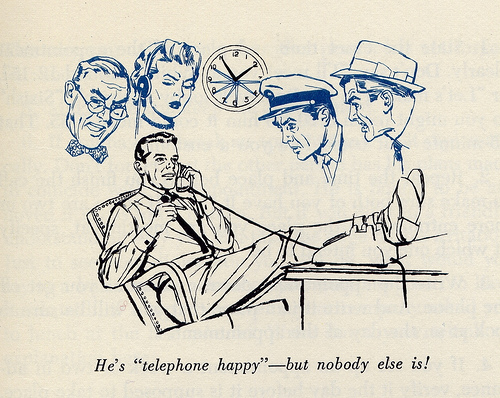

It’s easy. When Jay asks Ian how he thinks he can find his way out of this paralyzing ocean of choices, he answers: “I don’t know. I would say you pick a direction and start swimming. But you can’t tell one way from the other, so you can’t pick. You can’t even tell if you’re swimming toward something, so why would you use up all your energy going the wrong way?” Then he adds with relief, “I guess all you can do is hope someone comes along in a boat or something.”

That’s the mindset of a lot of twentysomethings – they’re waiting for their ship to come in. They want their life to be great and exciting and adventurous, but they think that it will just sort of fall into place for them somehow. Jay explains how this mindset is actually just a defense mechanism, a hedge against fear:

“There is a certain terror that goes along with saying ‘My life is up to me.’ It is scary to realize there’s no magic, you can’t just wait around for something. Not knowing what you want to do with your life—or not at least having some ideas about what to do next—is a defense against that terror. It is a resistance to admitting that the possibilities are not endless. It is a way of pretending that now doesn’t matter. Being confused about choices is nothing more than hoping that maybe there is a way to get through life without taking charge.”

Basically, what all the points above have in common is that they allow you to feel safe. But as we’ll discuss below, this feeling of safety is merely an illusion.

So how do you stop intentionally keeping yourself confused and let go of the myth of limitless possibilities in order to take charge of your life? The first order of business is dismantling that myth.

Everybody Starts with the Same Common Parts

The feeling of limitless possibilities, coupled with the barrage of “lifestyle design” rhetoric that is so popular these days, can blind you to the fact that life is still built out of the same, relatively few components that it always has been. Your future may seem vast and featureless at times, but it will be constructed – no matter how extraordinary you want it to be — with the same common “parts” that everyone uses.

Jay used the metaphor of a custom bicycle to finally get through to Ian. Ian worked at a bike shop and rode a custom model for transportation. He had put the bike together from various custom parts he had handpicked. But those parts were simply specialized versions of ones all bicycles include – frame, wheels, seat, gears, and so on.

Our lives are like that custom bike. We can all choose the parts that suit us best – and you may go out of your way to select unique, non-mass-produced versions — but they will come from the same main categories everyone else selects from. In building your life you basically have the following categories to work with: relationships, children, vocation, and travel/hobbies. So we can already narrow down our “limitless” possibilities into four divisions. How you arrange and how much you invest in each “part” is up to you. You might want a tandem bike (you prize marriage), but with mountain bike tires (you want to spend a lot of time outdoors), and a baby trailer on the back (definitely want kids). Someone else might want a one-seat bike with road tires meant for speed (doesn’t want to settle down) and a fixed gear (dedicated to a free, hip, artistic lifestyle). The combinations are endless, but we’re all just arranging the same common parts.

Getting Down to the Brass Tacks

”So everyone builds their life out of four main parts, but how do I know which kind of part to select from each category – we’ve organized the choices but there are still so many!”

Let’s think about this for a minute. The marriage and children question, if sticky in real life, is very straightforward – you either want to get hitched or you don’t, and want to have kids or you don’t. And when it comes to hobbies and what to do in our spare time, people feel pretty free in picking things up and putting them down without much pressure.

So when people say they don’t know what to do with their life, they’re really talking about one thing, even if in their cloud of uncertainty they don’t realize it: they’re not sure what to do for their vocation. Here the choices seem endless and the stakes terribly high. The fact that most of us still want those “ordinary” things like marriage and kids only creates an even greater sense of pressure about choosing a really special vocation; we fear if we don’t balance our traditional choices with something really unique, our lives will never rise to our vague vision of the extraordinary. We’ll have the same kind of lives our parents had! It is here, we feel, that we must hold the line on diverging from the ordinary, or risk never becoming the “special” people we always felt we were.

Thus there’s really only one category at the root of people’s gnawing uncertainty about their future. And despite the pressure we may feel in choosing the “right” career, the possibilities are not limitless here either. Our choices are greatly narrowed by several things. First, you’re not a blank slate; you’ve had more than two decades of experiences that have shaped you into the man you are today. All these years have strengthened some talents and abilities and weakened others, developed your values and beliefs, and honed some very distinct interests. Put these things together, and what you find is that as opposed to there being endless possibilities, most people are really drawn to, and have the aptitude for, no more than half a dozen vocational paths. Six is far more manageable than infinity. And of the handful of possibilities that really suit your talents, abilities, values, and interests, there’s probably one that calls to you the most, that nags at you the most often – even if questions and doubts about how you’re going to get there make you sometimes push it aside. This frontrunner choice, Jay suggests, may be for you what psychiatrist Christopher Bollas called the “unthought known” – “those things we know about ourselves but forget somehow.” You may shy away from thinking about it, and saying it out loud, but it’s there nonetheless.

Listen to my podcast with author and psychologist Meg Jay:

But What If I Make the Wrong Choice?!

Whether there’s one vocational opportunity that sticks out to you the most, or several that you feel equally drawn to, you may hesitate to move forward and claim one out of fear of making the wrong choice. As we discussed above, this fear can keep you in “my options are limitless” mode as you wait for the right choice to magically manifest itself. Here’s why you shouldn’t worry so much about making the “wrong” choice and should start on something, anything concrete, instead of living in limbo:

Not making a choice is a choice. The first thing to realize is that not making a decision isn’t any safer than making one. It feels safer in the short-term, but as Jay warns, “The consequences are just further away in time, like in your thirties or forties.”

Failure to make a choice is in fact a default choice. While making a concrete decision will shut some doors, at least for a time, not making a choice also closes numerous doors as well. Jay worked to get Ian to realize this:

“Ian would say, ‘I don’t want to settle for some ordinary thing.’ And I would say, ‘I’m not talking about settling. I’m talking about starting. Twentysomethings who don’t get started wind up with blank resumes and out-of-touch lives only to settle far more down the road. What’s so original about that?”

While deciding to pursue one path does close down other routes, at least for a time, it also opens up new ones that would never have been available if you remained at your initial starting point. For example, I went to three years of law school and yet never took the bar and became a lawyer. Was going to law school the “wrong” choice then? Not really. It prompted me to start a blog, which became my full-time profession. I never could have seen or even imagined that option from my starting point — never could have conceived the way one thing would lead to another — no matter how hard I squinted down that road.

Choosing one path doesn’t mean you’re stuck with it forever. Another thing to keep in mind is that just like the parts on a custom bike, if you try a part out, and it doesn’t work for you, you can always switch it out for another. Yes, every choice brings consequences, some that make it much harder to change course, but you don’t have to think of starting on a vocational path as a death sentence. As we previously wrote, learning new things throughout your life is easier now than ever before in history.

Employment experts say that this generation probably shouldn’t think they’ll have the same kind of job their whole life anyway. And many don’t even want to do the same exact thing their whole life, even if it’s something they enjoy.

What this generation needs most to succeed is both expertise and a broad range of skills (creativity, judgment, decision-making ability, social skills, etc.) – “identity capital” — they can take with them anywhere they go and will serve them well in any position. And here’s the good news, any experience, even if it doesn’t end up being your lifelong career, will build this important skill-set…

Every experience builds your identity capital. Seeing vocational pursuits as right or wrong is really the wrong way to look at it. Some experiences are better for us than others, but all experiences, if we have the right attitude and navigate them well, can be for our gain. Experiences are never a complete waste, as they can all add to our store of identity capital and connections with others. A course is only wrong if you see life as a linear pursuit, where each thing must lead directly to the next. If you instead see the point of life as gaining as many rich experiences as possible, learning and growing as much as you can, making a difference and contributing wherever you are, each avenue you pursue can be the right one, at least for a time.

You’ll never know if you like it, unless you try! You can, and should, do as much research about things you’re interested in pursuing as possible. But for many avenues, there isn’t any way of knowing if you’re going to like it before you actually try it. With that said, when you’re on a path, really be on it. Throw yourself into experiencing it; don’t sit on the fence and take a superficial temperature reading that won’t tell you what it’s really like. Before you decide you do want to change course, make sure you’ve run the one you’re on for all it’s worth.

Live with confidence and certainty. Believing that your options are limitless is intoxicating, but also anxiety-producing. Once you choose a path, you can feel the confidence and security that comes with having your feet firmly planted on the ground. That doesn’t mean uncertainty is a bad thing, or that you’ll never feel it again – it will return when it’s time to make another big decision. But it’s better to go from uncertainty to confidence and progress, then back to uncertainty and onwards again, than to completely stagnate in a cloud of bewilderment.

After Ian made a decision and went after and landed a graphic design job, he wrote to Jay:

“When I made the decision to come to D.C., I worried that by making one choice, I was closing all the other doors open to me at that moment. But it was sort of liberating to make a choice about something. Finally. And, if anything, this job has just opened more doors for me. Now I feel confident that I will have several iterations of my career—or at least time for several iterations—and that I will be able to do other things in life…

Above all else in my life, I feared being ordinary. Now I guess you could say I had a revelation of the day-to-day. I finally got it there’s a reason everybody in the world lives this way—or at least starts this way—because this is how it’s done.”

_____________________

Source:

The Defining Decade: Why Your Twenties Matter and How to Make the Most of Them Now by Meg Jay, PhD