What is a man? What sort of man should I be? What does it mean to live a good life? What is the best way to live and how do I attain excellence? What should I aim for, and what training and practices must I do to achieve those aims?

Such questions have been asked for thousands of years. Few men have grappled with them more, and provided keener insight to the answers, than the philosophers of ancient Greece. In particular, Plato’s vision of the tripartite nature of the soul, or psyche, as explained though the allegory of the chariot, is something I have returned to throughout my life. It furnishes an unmatched symbol of what a man is, can be, and what he must do to bridge those two points and attain andreia (manliness), arête (excellence), and finally eudaimonia (full human flourishing).

Today we will discuss that allegory and its meaning. While an understanding of the whole allegory and the pondering of it can bring great insight, the ultimate goal of this article is in fact to lay the foundation for two more posts to come in which we will uncover the nature of the one component of Plato’s vision of the soul that has almost entirely been lost to modern men: thumos.

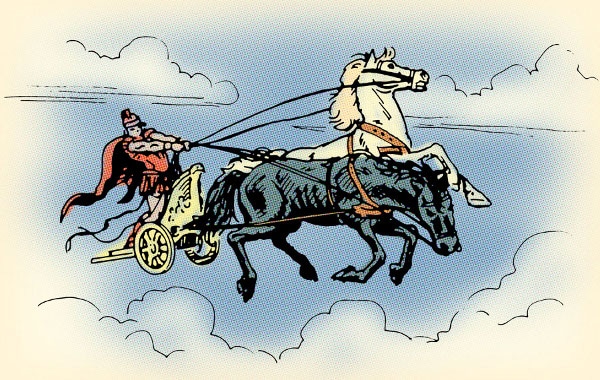

The Allegory of the Chariot

In the Phaedrus, Plato (through his mouthpiece, Socrates) shares the allegory of the chariot to explain the tripartite nature of the human soul or psyche.

The chariot is pulled by two winged horses, one mortal and the other immortal.

The mortal horse is deformed and obstinate. Plato describes the horse as a “crooked lumbering animal, put together anyhow…of a dark color, with grey eyes and blood-red complexion; the mate of insolence and pride, shag-eared and deaf, hardly yielding to whip and spur.”

The immortal horse, on the other hand, is noble and game, “upright and cleanly made…his color is white, and his eyes dark; he is a lover of honor and modesty and temperance, and the follower of true glory; he needs no touch of the whip, but is guided by word and admonition only.”

In the driver’s seat is the charioteer, tasked with reining in these disparate steeds, guiding and harnessing them to propel the vehicle with strength and efficiency. The charioteer’s destination? The ridge of heaven, beyond which he may behold the Forms: essences of things like Beauty, Wisdom, Courage, Justice, Goodness — everlasting Truth and absolute Knowledge. These essences nourish the horses’ wings, keeping the chariot in flight.

The charioteer joins a procession of gods, led by Zeus, on this trip into the heavens. Unlike human souls, the gods have two immortal horses to pull their chariots and are able to easily soar above. Mortals, on the other hand, have a much more turbulent ride. The white horse wishes to rise, but the dark horse attempts to pull the chariot back towards the earth. As the horses pull in opposing directions, and the charioteer attempts to get them into sync, his chariot bobs above the ridge of heaven then down again, and he catches glimpses of the great beyond before sinking once more.

If the charioteer is able to behold the Forms, he gets to go on another revolution around the heavens. But if he cannot successfully pilot the chariot, the horses’ wings wither from lack of nourishment, or break off when the horses collide and attack each other, or crash into the chariots of others. The chariot then plummets to earth, the horses lose their wings, and the soul becomes embodied in human flesh. The degree to which the soul falls, and the “rank” of the mortal being it must then be embodied in is based on the amount of Truth it beheld while in the heavens. Rather like the idea of reincarnation. The degree of the fall also determines how long it takes for the horses to regrow their wings and once again take flight. Basically, the more Truth the charioteer beheld on his journey, the shallower his fall, and the easier it is for him to get up and get going again. The regrowth of the wings is hastened by the mortal soul encountering people and experiences that contain touches of divinity, and recall to his memory the Truth he beheld in his preexistence. Plato describes such moments as looking “through the glass dimly” and they hasten the soul’s return to the heavens.

Interpreting the Allegory

Plato’s allegory of the chariot can be interpreted on a number of levels – as symbolic of the path to becoming godlike, spiritual transcendence, personal progress and attainment of “Superhuman” status, or psychological health. There is much one can ponder about it. Below we delve into several of the main points.

The Tripartite Soul

The chariot, charioteer, and white and dark horses symbolize the soul, and its three main components.

The Charioteer represents man’s Reason, the dark horse his appetites, and the white horse his thumos. We’ll explore the nature of thumos in-depth next time, but for now, you can read it simply as “spiritedness.” Another way to label the three elements of soul are as the lover of wisdom (charioteer), the lover of gain (dark horse), and the lover of victory (white horse). Aristotle described the three elements as the contemplative, hedonistic, and political, or, knowledge, pleasure, and honor.

The Greeks saw these elements of soul as physical, almost independent entities, not so much with bodies, but as real forces, like electricity that could move a man to act and think in certain ways. Each element has its own motivations and desires: reason seeks truth and knowledge, the appetites seek food, drink, sex, and material wealth, and thumos seeks glory, honor, and recognition. Plato believed reason has the highest aims, followed by thumos, and then the appetites. But each soul force, if properly harnessed and employed, can help a man become eudaimon.

Reason’s job, with the aid of thumos, is to discern the best aims to pursue, and then train his “horses” to work together towards those aims. As the charioteer, he must have vision and purpose – he must know where he is going — and he must understand the nature and desires of his two horses if he wishes to properly harness their energies. A charioteer can err by either failing to hitch one of the horses to the chariot altogether, or by failing to bridle the horse, and instead letting him run wild. In the latter case, Plato argued, “the best part [Reason] is naturally weak in a man so that it cannot govern and control the brood of beasts within him but can only serve them and can learn nothing but the ways of flattering them.”

Obtaining Harmony of Soul

The masterful charioteer does not ignore his own motivations, nor the desires of thumos and appetite, but neither does he let his two horses run wild. He lets Reason rule, takes stock of all his desires, identifies his best and truest ones – those that lead to virtue and truth — and guides his horses towards them. He does not ignore or indulge them – he harnesses them. Each horse has its strengths and weaknesses, and the white horse can lead a man into the wrong path just as the dark horse can, but when properly trained, thumos becomes the ally of the charioteer. Together, reason and thumos work to pull the appetites into sync.

Instead of having “civil war amongst them,” the deft charioteer understands each role the three forces of his soul play, and he guides them in carrying out that role without either entirely usurping their role, nor allowing them to interfere with each other. He achieves harmony amongst the elements. Thus, instead of dissipating his energies in contradictory and detrimental directions, he channels those energies towards his goals.

Achieving this harmony of soul, Plato argues, is a precursor to tackling any other endeavor of life:

“having first attained to self-mastery and beautiful order within himself, and having harmonized these three principles, the notes or intervals of three terms quite literally the lowest, the highest, and the mean, and all others there may be between them, and having linked and bound all three together and made of himself a unit, one man instead of many, self-controlled and in unison, he should then and then only turn to practice if he find aught to do either in the getting of wealth or the tendance of the body or it may be in political action or private business, in all such doings believing and naming the just and honorable action to be that which preserves and helps to produce this condition of soul.”

The foundational nature of gaining mastery over one’s soul, Plato continues,

“is the chief reason why it should be our main concern that each of us, neglecting all other studies, should seek after and study this thing—if in any way he may be able to learn of and discover the man who will give him the ability and the knowledge to distinguish the life that is good from that which is bad, and always and everywhere to choose the best that the conditions allow.”

A man that makes this pursuit his aim, and allows it to guide all his thoughts and actions, “will gladly take part in and enjoy those which he thinks will make him a better man, but in public and private life he will shun those that may overthrow the established habit of his soul.”

Taking Flight and Progressing in Our Journey

As you’ll remember, in the allegory of the chariot, the chariot falls from the heavens when the horses do not receive adequate nourishment from the Forms, or when the horses rebel and the charioteer does a poor job of directing them. They lose their wings, and must stay on earth until they regrow – a process which is hastened by remembering what one saw before the fall.

Plato believed that discovering all truth was not a process of learning, but of remembering what one once knew. His philosophy may be interpreted literally as saying we had a preexistence before this life. But it also has meaning in a more figurative sense. We get off track in becoming the men we wish to be when we succumb to vice (being overpowered by the dark horse), and we tend to succumb to vice when we forget who we are, who we want to be, and the insights into those two pieces of knowledge we have already attained and experienced. Doing things that remind us of the truths we hold dear keeps us “in flight” and progressing with our lives.

For more on this important subject, I highly recommend reading: Hold Fast: How Forgetfulness Torpedos Your Journey to Becoming the Man You Want to Be, and Remembrance Is the Antidote

Understanding the Dark Horse

In order to train and harness the power latent in the forces of his soul, a man must understand the nature of his “horses” and how to utilize their strengths and rein in their weaknesses.

A man’s dark horse, or appetites, are not difficult to understand; you have probably felt its primal pull towards money, sex, food, and drink many times in your life.

But despite our intimate acquaintance with our appetites, or perhaps because of it, the dark horse is not easy to properly train and make use of. Doing so requires achieving moderation, or as Aristotle would put it, finding the “golden mean” between extremes.

A man who lets his appetites run completely wild is the unabashed hedonist. He does not seek to rein in the dark horse at all, letting him pull the chariot after whichever pleasure crosses its path. This is the man who lives for nothing higher than to eat good food, get drunk, have sex, and make money. He seeks after effeminizing luxury with abandon and will do anything to get it. With no check to his behavior, the result can be a giant gut, pickled brains, massive debt, and a prison sentence for corruption.

A life wholly dedicated to the satisfaction of one’s bodily and pecuniary pleasures make man no different than the animals. Aristotle called such a life bovine, and Plato argued that the result of letting oneself be dominated by his appetites “is the ruthless enslavement of the divinest part of himself to the most despicable and godless part.” Such a man, Plato submitted, should be “deemed wretched.”

On the other end of the spectrum is the man who sees his physical desires as wholly wrong or sinful – troublesome or evil stumbling blocks on the path to spiritual purity or enlightenment. This man seeks to nullify his flesh, and cut off its cravings for pleasure entirely. This is the man who spends so much of his life thinking of sex as sinful, that he can’t turn off that association and enjoy it, even after he is married. He averts his eyes from women as living porn. Food is merely fuel. He often seems flat, sterile, and closed off to others, though often you can sense the bottled impulses bubbling beneath the surface that he’s tried so hard to deny. And because of the lack of a healthy outlet, that bubbling often becomes a toxic stew that will one day burst forth in a decidedly unhealthy way.

Plato believed that the appetites were the lowest of the forces of the soul, and that allowing the dark horse to dominate and enslave you would lead to a base, unvirtuous life far from arête and eudaimonia. Yet he also argued that the dark horse, if properly trained, imparted just as much energy to the pulling of the chariot as the white horse did. The chariot that soars highest makes use of both horses side by side. A would-be ace charioteer neither entirely indulges his dark horse nor wholly cuts him off. He harnesses and directs the energy in a positive way.

Between the two extremes of unchecked hedonism and the iron-fisted squashing of bodily appetites lies a middle way. This is the man who maintains a sense of sensuality and earthiness, who makes room for the pleasures of body and money but puts them in their proper place, who, as Dr. Robin Meyers puts it, is able to find “the virtue in the vice.” He enjoys sex thoroughly, but does so within the context of love and commitment. He enjoys good food and drink, without mindlessly engorging and imbibing. He appreciates money, and that which it can buy, but does not make acquiring it his central aim.

The dark horse, when properly trained and directed, can lead one closer, not further from the good life. Pleasures satisfied with discretion make a man happy and balanced, and keep him feeling healthy and motivated enough to tackle his higher goals. And the appetites themselves can lead directly to those loftier aims. The desire for money, when kept in balance, can lead to success, recognition, and independence. Lust, when properly directed, leads a man to love, and Plato believed that beholding one’s lover was a central path to recalling the Beauty of the Forms, and regrowing one’s wings for another trip into the heavens.

That is the nature of the dark horse – a force that can be used for both good and ill, depending on the mastery of the charioteer. It is fairly easy to grasp, if not always to live. But what of the white horse, thumos? That is another matter. There is no word in our modern language equivalent to this ancient concept. We have here rendered it “spiritedness,” but in truth it encompasses much, much more. It is to that subject we will turn next time.

Read Part II: Got Thumos?

____________

You can read the entire Phaedrus online for free here. Plato/Socrates hit the subject from another angle and metaphor – that of a rational man, lion, and hydra-like beast – in Book IX of the Republic.

Illustration by Ted Slampyak