‘Tis the season for hot cocoa.

At least it is for red-cheeked children who are looking to warm up after coming in from a well-spent snow day.

And for lady folk curled up in a blanket watching The Shop Around the Corner.

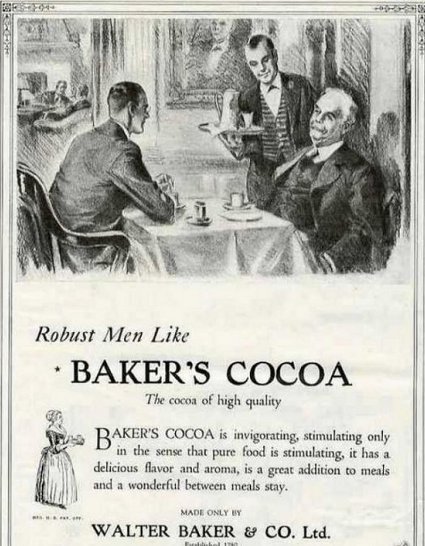

But a man, he’s sitting by the fire in his leather chair, drinking a properly manly drink like black coffee, or scotch, perhaps.

Such is the perception of cocoa these days. It is but a sweet confection a man might drink a few times each year, if at all.

For thousands of years, however, it was quite a different story. While we tend to think of chocolate today in its solid form, for nine-tenths of its long history, chocolate was a drink – the first true chocolate bar as we now know it was not invented until 1839. In the thousands of years before that time, chocolate was seen as an invaluable, sacred, even magical beverage — a symbol of power, a privilege of warriors and the elite, and a satisfying tonic that was consumed daily and offered the sustenance needed to tackle virile challenges.

Contrary to its ho-hum, sometimes even junk food-y reputation, real chocolate is an incredibly complex substance, containing 400-500 different compounds. Among those compounds are several with mind and body boosting benefits:

- Caffeine – a stimulant present in small amounts, depending on the type and amount of chocolate ingredients.

- Theobromine – a mild stimulant distinct from caffeine which provides the lion’s share of chocolate’s kick and energizes without greatly activating the central nervous system the way the former does. It also enhances mood, dilates blood vessels, can lower blood pressure, relaxes the smooth muscles of the bronchi in the lungs, and can be used as a cough medicine.

- Tryptophan — releases the feel-good neurotransmitter serotonin in the brain.

- Phenylethylamine – functions similarly to amphetamines in releasing norepinephrine, which increases excitement, alertness, and decision-making abilities, and dopamine, which releases endorphins (natural painkillers) and heightens mood.

- Flavonoids – antioxidants which may improve blood flow to the heart and brain, prevent clots, improve cardiac health, and act as anti-inflammatories.

Chocolate has also for centuries been rumored to be an aphrodisiac.

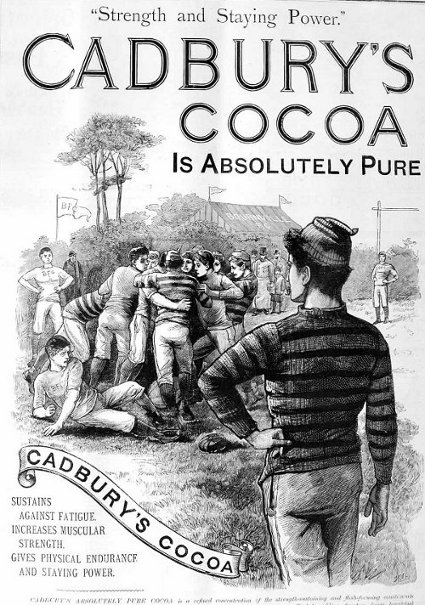

In short, hot cocoa is a powerful elixir – one which boosts mood and vitality and combats stress, anxiety, and pain. For good reason is the chocolate tree’s scientific name — Theobroma cacao — ancient Greek for “food of the gods.” For what other drink tastes great, is filling in nature, and stimulates mind and body?

No wonder then that this beverage, far from being a kiddie drink, has been a favorite of rulers, warriors, and explorers for centuries.

A Note on Terminology: Hot Chocolate vs. Hot Cocoa

While hot chocolate and hot cocoa are often used interchangeably, they’re not actually the same thing. Chocolate begins as cacao seeds (often referred to as cocoa beans) that grow in pods on the bark of the tropical Theobroma cacao tree. These seeds are then fermented, dried, and roasted. The shells are removed, leaving the cacao nibs. The nibs are crushed into a thick paste called chocolate liquor (despite the name, it does not contain alcohol), which is made up of cocoa solids and cocoa butter. The ancient peoples of Mesoamerica mixed this paste with water to make a highly-prized beverage.

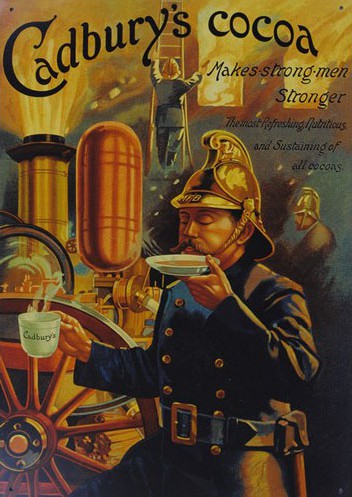

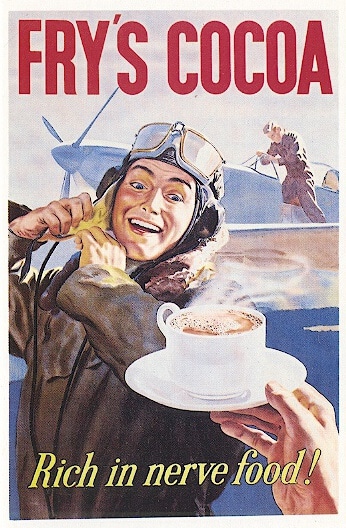

Before there was Red Bull…there was cocoa.

Chocolate was made this way and consumed almost entirely as a drink until 1828 when Dutch chemist Coenraad Johannes van Houten invented a process that could separate out most of the fat — the cocoa butter — from the chocolate liquor, leaving a dry cake that is then pulverized into cocoa powder. Before undergoing this “Dutching” process, the nibs are treated with alkaline salts to neutralize their acidity, mellow the flavor, and improve the cocoas’ miscibility in warm water. The end result is “Dutch cocoa.” “Natural cocoa” is that which does not undergo this Dutching process.

To make quality solid chocolate, cocoa butter is re-added to the chocolate liquor, along with other ingredients like sugar, vanilla, and milk.

So, hot cocoa is made with cocoa powder, either Dutch or natural, and hot chocolate is made with little pieces or shavings of solid chocolate. The latter is sometimes also called “drinking chocolate.” Both are delicious.

Drink of the Gods: Chocolate in Ancient Mesoamerica

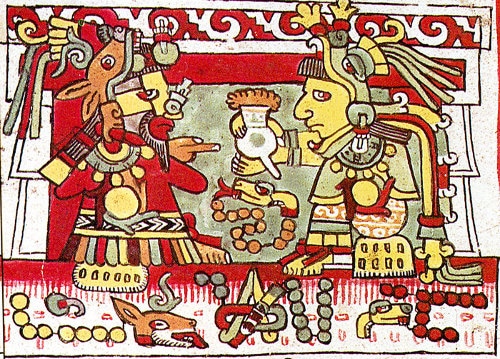

The earliest cultivation of cacao can be traced to ancient Mesoamerica, in which it served a religious, financial, and nutritional purpose.

The drink that was made with cacao, xocolātl, wasconsidered sacred by the Mesoamericans and used during initiation ceremonies, funerals, and marriages. Cacao beans were also used as currency. Because cacao was both currency and food, drinking chocolate was like sipping on cash — kind of like lighting your cigar with a hundred dollar bill – and for this reason was a privilege mainly limited to elites.

Cacao was cultivated and consumed by the Olmecs and Mayans, but is most famously associated with the Aztec civilization. Montezuma the II, who kept a huge storehouse of cacao (supplied by conquered peoples from whom he demanded the beans as tribute) and drank 50 golden goblets of chocolate a day, decreed that only those men who went to war could imbibe cacao, even if they were his own sons. This limited chocolate consumption to royals and nobles who were willing to fight, merchants (their travels through hostile territory necessitated their taking up of arms), and warriors. For the latter, chocolate was a regular part of their military rations; ground cacao that had been pressed into wafers and could be mixed into water in the field were given to every solider on campaign. The drink provided long-lasting nourishment on the march; as one Spanish observer wrote, “This drink is the healthiest thing, and the greatest sustenance of anything you could drink in the world, because he who drinks a cup of this liquid, no matter how far he walks, can go a whole day without eating anything else.”

All Aztecs thought of both blood and chocolate as sacred liquids, and cacao seeds were used in their religious ceremonies to symbolize the human heart – harkening to their famous ritual in which this still-beating organ was torn from a sacrificial victim’s chest. The connection between blood and chocolate was especially strong for warriors, and it was served at the solemn initiation ceremony of new Eagle and Jaguar knights, who had to undergo a rigorous penance process before joining the most elite orders of the Aztec army.

In peacetime, chocolate was an after-dinner drink, served along with smoking tubes of tobacco, much in the way modern gentlemen once enjoyed brandy and cigars after a meal (and still do). The Mayans liked their chocolate hot, the Aztecs liked it cold, but all Mesoamericans preferred it foamy – a quality that was accomplished by pouring the chocolate back and forth from a bowl held high into one below (a large, foam-creating swizzle stick was added later through a Spanish creolization of the practice).

Mesoamerican chocolate, unless honey was added, was also bitter. To this strong, bitter brew was added a great variety of spices and seasonings, such as ground up flowers and vanilla. The Aztecs were especially fond of adding chili pepper, which gave the drink a delightful burn going down. Maize was often added to stretch the chocolate and turn it into a more filling gruel, but this version was considered inferior to the pure, potent variety.

The Beverage of Movers and Shakers in Europe

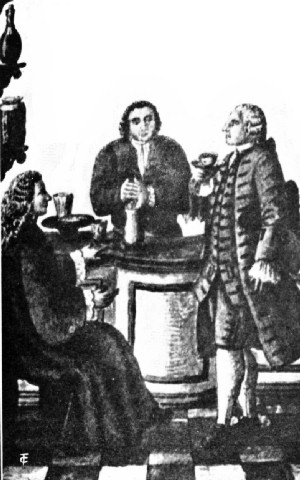

When chocolate was brought back to Spain in the 17th century by conquistadors, it quickly spread throughout Europe, where it continued to be considered a luxury and a drink of the elites. Originating on the continent from Spain, and more expensive than coffee, chocolate was seen as southern, Catholic, and aristocratic, while coffee was viewed as northern, Protestant, and middle-class.

Chocolate was a popular beverage among monks and priests; Jesuits ran some cacao plantations in the New World. According to the Dominican School of Philosophy and Theology, many of “the first recipes using cacao beans came from a 12th century Cistercian monastery, Monasterio de Nuestra Señora de Piedra monasterio. Extant documents indicate that by 1534 it is already a staple in the monastic kitchen. According to tradition, a Franciscan friar, Fray Jerónimo de Aguilar, who had traveled with Cortéz, gave a recipe and some beans to Don Antonio de Álvero, the Abbot of the Monastery. As depicted in this photo – located at the Monasterio de Piedra – Cistercian communities, even to this day, often have a room located above the cloister, known as the chocolatería, used specifically for the preparation and enjoyment of chocolate.” Interestingly, the popularity of drinking chocolate among Catholics led to sometimes fervent debate over whether it was a drink or a food, and thus whether it could, or could not, be consumed during times of fasting.

Yet with the Spanish revival of the Mayan practice of drinking chocolate hot and the welcome addition of milk and sugar, the beverage soon won converts from many corners – many of whom began to give the ancient drink some twists of their own. The addition of cinnamon and black pepper was popular, as was ambergris, a solid, fatty substance found in the intestines of sperm whales, and musk, secreted by the glands of the Himalayan musk deer (and believed to be an aphrodisiac). Other drinkers experimented with throwing orange peel, rose water, cloves, ground up pistachios and almonds, or egg yolks into the brew.

Chocolate was drunk in large cups at Spanish bullfights, and began to be served across Europe both at dedicated “chocolate houses” and at coffee houses, where members of the upper class gathered to sip hot beverages, gamble, and discuss the pressing philosophical and political issues of the day. In England, each establishment was typically associated with one of the Parliamentary parties, and often turned into full-on gentlemen’s clubs. For example, the Cocoa-tree Chocolate House, located on St. James Street in London, was patronized by the Tory party, and then became the Cocoa Tree Club; eminent men like Jonathan Swift and Edward Gibbon were members. Mrs. White’s Chocolate House, another Tory establishment, was created on Chesterfield St. in 1693; it was famous not only for its chocolate but as a notorious center of gambling – the gaming room was nicknamed “Hell” and patrons placed bets on everything from elections to which raindrop would make it to the windowpane first. The chocolate house moved to St. James Street in 1778 and transformed into an official, and highly elite, gentlemen’s club. Over 300 years later, it is still around and now simply called White’s. The club’s rolls have included three monarchs and a huge consortment of other royals, nobles, and prime ministers.

Fueling Expeditions to the Ends of the Earth

With its hot, filling, rejuvenating qualities, cocoa has been an essential staple on all the major expeditions to the North and South Poles. Explorers and their teams of men would drink cup after cup of it as a bulwark against the morale and strength-sapping task of trudging across an icy, austere landscape.

The daily ration for Robert Falcon Scott’s trek to the South Pole: 450g biscuit, 340g pemmican, 85g sugar, 57g butter, 24g tea, 16g cocoa.The sugar was mixed into the cocoa, and Scott said, prevented the men from wanting to kill each other. As a side note, these rations only provided each man about 4,500 calories a day, at least 2,000 less than is needed for sledging, which is why the men starved and died on their return from the Pole. Roald Amundsen, who beat Scott to the Pole, and actually gained weight on the way back, brought five times as much cocoa.

During Robert Falcon Scott’s ill-fated attempt to be the first to reach the South Pole, he had his men drink hot cocoa five nights a week. Each evening when they stopped for supper, they warmed up one pot of what they called “hoosh” — a thick stew made with pemmican (dried beef and fat) and hard biscuits – and a pot of cocoa. They washed the former down with the latter. While as one of his men, Apsley Cherry-Garrard, recorded in his dairy, “Many controversies raged over the rival merits of tea and cocoa,” and some of the men preferred the former, Scott preferred cocoa for its milder stimulation. As Cherry-Garrard noted, “the warmth of your hours of rest depends largely on getting into your bag immediately after you have eaten your hoosh and cocoa,” and having to get out of the bag during the night, exit the tent, and expose one’s peppermint stick to the cold was not a thought anyone relished. Scott compromised by allowing tea two evenings a week. He also had his men drink cocoa in the mornings to get something substantial and invigorating in their stomachs while minimizing bathroom breaks on the march.

Apsley Cherry-Garrard (right), a member of the Terra Nova Expedition, was asked by Scott to man-haul a sledge 60 miles to Cape Crozier to retrieve an Emperor penguin egg. The men became pinned down by a blizzard, their tent blew away, and they laid in their sleeping bags exposed to the falling snow and -40 degree temperatures. It was so cold, Cherry-Garrard shattered most of his teeth because they chattered so hard. The men returned to the base camp a month later exhausted and frozen and were revived with cups of cocoa. In his account of the horrific experience, The Worst Journey in the World, Cherry-Garrard mentions cocoa no less than two dozen times, saying, “there was always plenty to be had,” and calling it “the most satisfying stuff imaginable” and “the most comforting drink.”

In 1989, when American explorer Will Steger spent 220 days traveling almost 4000 miles in the first dog-sled traverse of Antarctica, he and his international team of five others went through 2,070 cups of Swiss Miss.

Hot Cocoa on the Front Lines

Beginning with the Aztec warriors, chocolate and cocoa has been included in military rations for centuries.

During the Revolutionary War, officers often breakfasted on chocolate and members of the Continental army were given a monthly allotment of chocolate according to rank; colonels and chaplains received four pounds of chocolate, majors and captains three pounds, lieutenants two pounds, and so on. This chocolate ration was created by smooshing prepared cacao nibs into a cake. With their pocket knives, soldiers would shave pieces of the cake off into a pot of boiling water. The resulting drink was considered rejuvenating, and much of the chocolate available went to hospitals to help the sick and wounded get their strength back.

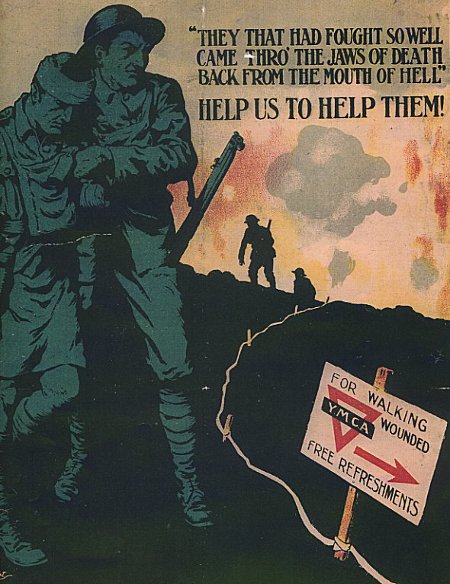

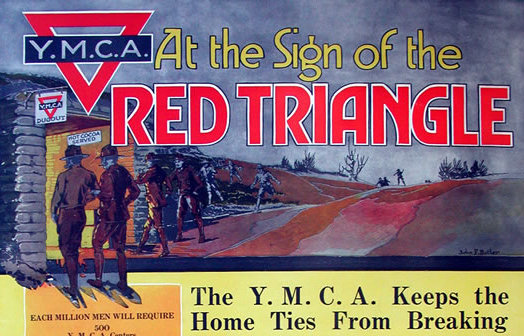

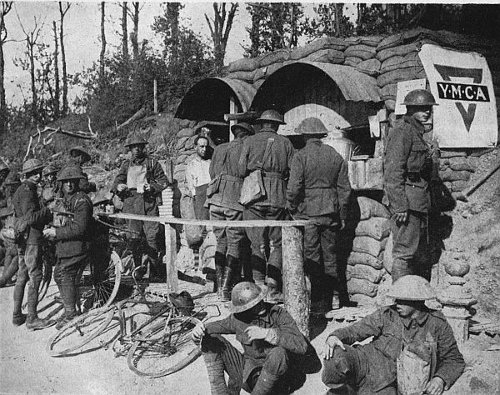

The invention of cocoa powder made “chocolate” easier for soldiers to carry and prepare while on campaign. But during World War I, before true field rations had been invented, troops were often supplied with hot cocoa by YMCA volunteers. In a time where the military had not yet developed its own morale, welfare, and comfort services, the YMCA took on this role, sending 25,000 volunteers to military units and bases from Egypt to France. Among their many services, “Red Triangle Men,” as they were called, set up comfort huts and canteens, often quite close to the battlefield, where soldiers could come for food, smokes, and cup after cup of piping hot cocoa after a firefight.

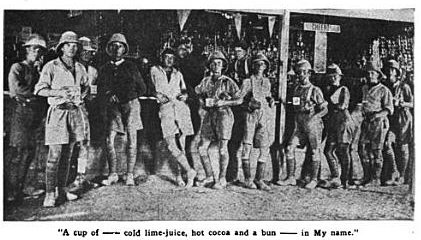

YMCA canteen in Egypt.

A “Y” man serves hot chocolate in the Toulon Sector, March 22, 1918. Said one solider, the cocoa made them “feel like new men.”

“Once again the Ypres Salient was resounding with intense artillery fire. The British regulars had blown up six giant craters in the enemies’ lines at St. Eloi and the Canadians were holding the captured territory. But the ground was held at great cost. Our men were returning wounded, broken, and weary. In those days both the man and the dug-out were needed. Early and late he toiled over a troublesome gasoline stove to prepare hot cocoa for the wayfarers. A constant stream of heroes came down the road. “Walking patients,” men who had not been too severely wounded, in the head or arm, were sent from the trench dressing station to the field dressing station lower down. Some who passed by had been buried by “Rum Jars”; others were victims of shell concussion, but most of them had been struck by shrapnel and were faint with loss of blood. Wounds had taken all the “sand” out of them, and the hot cocoa was a welcome tonic for the weary and wounded marchers.” -Young Men, Vol. 43, 1917

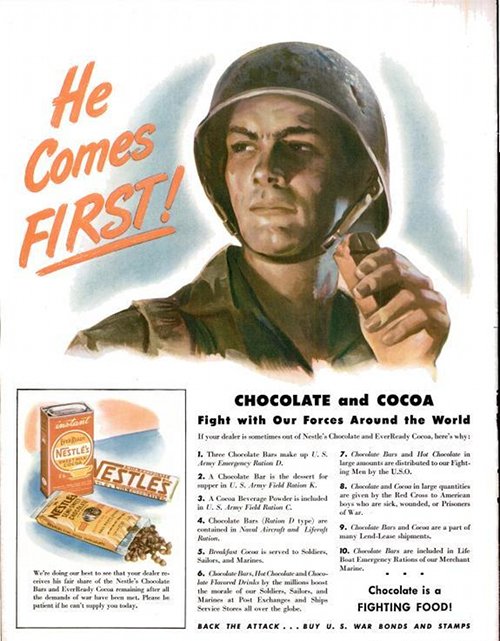

During WWII, new kinds of combat rations were developed, including the C-Ration. The C-Ration was a two-can meal, consisting of an M-unit – an entrée, like meat stew — and a B-unit – bread and dessert. The latter originally contained 5 hardtack crackers, 3 sugar tablets, 3 Dextrose energy tablets, and a packet of beverage mix (instant coffee, powdered lemon drink, or boullion soup powder). In 1944, the beverage list was expanded and a disc of sweetened cocoa was added to the choices.

Cocoa mix was added to the C-ration in 1944.

In the years after the war, the C-Ration was modified and revised and went through several subsequent variations. In 1954, the C-4 was released, which added, among other things, sugar and non-dairy creamer to the mix. Soldiers often used one package of each to enhance their cocoa.

C-Rations were phased out in 1958, although Vietnam soldiers continued to receive cases of them marked with dates from the 1950s. To replace the C-Ration, the military developed the “Meal, Combat, Individual,” or MCI, which included more variety than its predecessor. Four different B-unit cans were available, including the B-3, which contained 4 cookies and a packet of cocoa mix. Cocoa packets were prized and nonsmokers would trade their cigarettes (4 were included in the MCI’s “Accessory Pack”) for them. Some of the men would add the cocoa to their coffee to make a mocha beverage. If they were out of cocoa, the men would heat up water inside a can, chop up their Tropical Bar (a heat resistant chocolate bar that came in their sundries kit) into the water, and add a packet of creamer and sugar to make a hot and satisfying drink.

Cocoa mix is still included in MREs, which began to replace MCIs in the 70s and 80s.

Celebrate the Holidays (and Beyond!) with This Virile Elixir!

If this post has you hankering for a cup of cocoa, here are a few tips to get the most out of this virile beverage.

Hot cocoa is deceptively easy to make at home. Dark chocolate has as much as three times more flavonoids than wine and green tea, and cocoa powder has more of them than solid dark chocolate does. However, because the alkalizing process that Dutch cocoa undergoes saps 60-80% of its flavonoids (although cocoa is so high in them that actually still leaves a whole lot), you may want to look for natural cocoa to get the most potent dose.

Prepared cocoa mixes also oftentimes contain more sugar than cocoa, so add a little sugar or a natural sweetener (like stevia) to an unsweetened variety as desired. Mark, of Mark’s Daily Apple, drinks it as a rare holiday indulgence (he’s not a proponent of regularly consuming dairy) straight up in his milk, arguing that the leche adds enough natural sweetness on its own. Unfortunately, studies have shown that dairy may inhibit antioxidant activity and absorption in the body, so if you’re looking to get those benefits, you may just want to mix it in almond or coconut milk, or straight up in hot water. You can even create a truly potent tonic using raw, ground-up cacao nibs, just like a proper Mayan. (Bonus: cacao nibs are an excellent source of magnesium, which naturally helps boost testosterone – perhaps there’s something to the old idea of chocolate as an aphrodisiac after all…)

Of course, as mentioned at the start, antioxidants are not the only benefit of chocolate, and its feel-good properties are only enhanced with a little sugar and milk at the proper time. Like on a backpacking trip, or, say, while riding the Polar Express. Can I be the only one who thought as a boy that the mention of “hot cocoa as thick and rich as melted chocolate bars” was one of the most memorable parts of that book?

Mmmm, I think I’m going to make a creamy mug and go sit down by the fire. Eat, or as it were, tear your heart out, Aztec warrior.

________________

Sources:

The True History of Chocolate by Sophie D. Coe and Michael D. Coe

Chocolate: History, Culture, and Heritage by Louis E. Grivetti and Howard-Yana Shapiro