I’m a big fan of the classic 1960s-era television show, The Twilight Zone. Even when you can see the episodes’ famous twists coming a mile away, they’re still enjoyable to watch, as the show managed to niftily combine elements of science-fiction, suspense, psychological thrills…and even a little social commentary and abstract philosophy.

One of my favorite episodes is #28: “A Nice Place to Visit.” You can stream it for free from Amazon (if you’re an Amazon Prime member), or watch it with foreign language subtitles in the YouTube clip below:

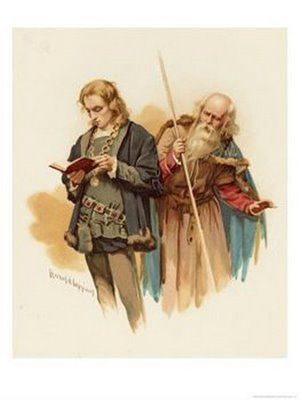

The episode opens with one Rocky Valentine, lifelong troublemaker and tough guy, robbing a pawn shop after killing the night watchman. The police arrive and open fire on Rocky as he tries to get away. Rocky returns fire and the officers pump him full of lead. He awakens to find himself unharmed, with a kindly Colonel Sanders-esque man by his side. The older gentleman introduces himself as Pip, and informs Rocky that he knows everything about him, and that as his guide, he is devoted to giving Rocky everything he wants, whatever that might be. Rocky, not yet realizing he is dead, is at first quite wary, but as Pip sets him up in a posh apartment and produces a sharp wardrobe, wads of cash, and beautiful dames seemingly out of thin air, Rocky is dazzled and giddy. Anything he desires becomes his: whenever he gambles, he wins on every bet; when he fills up the ash trays in his hot rod, he simply orders up another.

Not believing his good fortune, Rocky keeps asking Pip: “What’s the pitch, the catch, the gimmick?” Pip finally reveals that Rocky is dead and is alone in a private domain set up just for him. Looking around at his wish-fulfillment-world, Rocky concludes that he therefore must be in Heaven. Given the spotty record of his mortal life, he’s not sure how he got past the pearly gates, but he plans to enjoy it to the fullest and revels in every pleasure he can dream up.

Yet after a month, Rocky feels crazily restless and bored out of his mind. The thrill of winning at every hand has become stale; he’s tired of the women who dote on him. Rocky figures his unhappiness stems from not fitting in in Heaven. “I don’t belong in heaven. I want to go to the other place,” he tells Pip. “Heaven?!” Pip exclaims. “Whatever gave you the idea you were in Heaven, Mr. Valentine? This is the other place!” Cue the maniacal laughter.

Can’t Have the Bitter Without the Sweet

The message of “A Nice Place to Visit” is that while we might think that a world without risk or challenge, without pain or heartache, a world where our every wish is fulfilled would be heaven and bring us boundless joy, it would, in fact, make us absolutely miserable and be a certain kind of hell. Without risk there can be no satisfaction in the reward. Without misery there can be no joy. Without the bitter there can be no sweet.

Without opposition in all things, there would be no contrast in our experiences, and without contrast with something else, a thing would essentially cease to exist; for example the fish does not understand what water feels like, or that it even lives in something called “water,” for it is completely enveloped in it. But a fish that is scooped out in a net, and then placed back in the water, does then gain the knowledge of what water is, and how exquisite it feels to be surrounded by it.

Rod Serling (creator of The Twilight Zone) was of course not the first to expound on this bitter-sweet concept–it has been explored by prophets and philosophers for thousands of years.

For example in the first century AD, the Stoic philosopher and statesman Seneca penned the following dialogue, arguing that not only was true happiness impossible without hardships, but that virtue, and thus real greatness, was too:

“Prosperity comes to the mob, and to low-minded men as well as to great ones; but it is the privilege of great men alone to send under the yoke the disasters and terrors of mortal life: whereas to be always prosperous, and to pass through life without a twinge of mental distress, is to remain ignorant of one half of nature. You are a great man; but how am I to know it, if fortune gives you no opportunity of showing your virtue?

You have entered the arena of the Olympic games, but no one else has done so: you have the crown, but not the victory: I do not congratulate you as I would a brave man, but as one who has obtained a consulship or praetorship. You have gained dignity. I may say the same of a good man, if troublesome circumstances have never given him a single opportunity of displaying the strength of his mind. I think you unhappy because you never have been unhappy: you have passed through your life without meeting an antagonist: no one will know your powers, not even you yourself.

For a man cannot know himself without a trial: no one ever learnt what he could do without putting himself to the test; for which reason many have of their own free will exposed themselves to misfortunes which no longer came in their way, and have sought for an opportunity of making their virtue, which otherwise would have been lost in darkness, shine before the world. Great men, I say, often rejoice at crosses of fortune just as brave soldiers do at wars. I remember to have heard Triumphus, who was a gladiator in the reign of Tiberius Caesar, complaining about the scarcity of prizes. “What a glorious time,” said he, “is past.”

Valour is greedy of danger, and thinks only of whither it strives to go, not of what it will suffer, since even what it will suffer is part of its glory. Soldiers pride themselves on their wounds, they joyously display their blood flowing over their breastplate. Though those who return unwounded from battle may have done as bravely, yet he who returns wounded is more admired…

Do not, I beg you, dread those things which the immortal gods apply to our minds like spurs: misfortune is virtue’s opportunity. Those men may justly be called unhappy who are stupified with excess of enjoyment, whom sluggish contentment keeps as it were becalmed in a quiet sea: whatever befalls them will come strange to them. Misfortunes press hardest on those who are unacquainted with them: the yoke feels heavy to the tender neck. The recruit turns pale at the thought of a wound: the veteran, who knows that he has often won the victory after losing blood, looks boldly at his own flowing gore…

There can be no easy proof of virtue. Fortune lashes and mangles us: well, let us endure it: it is not cruelty, it is a struggle, in which the oftener we engage the braver we shall become. The strongest part of the body is that which is exercised by the most frequent use: we must entrust ourselves to fortune to be hardened by her against herself: by degrees she will make us a match for herself. Familiarity with danger leads us to despise it. Thus the bodies of sailors are hardened by endurance of the sea, and the hands of farmers by work; the arms of soldiers are powerful to hurl darts, the legs of runners are active: that part of each man which he exercises is the strongest…

No tree which the wind does not often blow against is firm and strong; for it is stiffened by the very act of being shaken, and plants its roots more securely: those which grow in a sheltered valley are brittle: and so it is to the advantage of good men, and causes them to be undismayed, that they should live much amidst alarms, and learn to bear with patience what is not evil save to him who endures it ill.”

The above represents one of my favorite passages in ancient philosophy. Not only because it so powerfully explains the bitter-sweet concept, but because it also offers an answer to one of the questions theists have struggled with for millennia: “Why does God allow suffering in the world?” or “Why does God allow bad things to happen to good people?”

It is often argued that a loving God would not allow His children to suffer. But, if you subscribe to Seneca’s position that without hardships man can be neither happy nor virtuous, and if you believe that God desires his children to be both righteous and joyful, the question then becomes, “How could a loving God not allow suffering in the world?”

And yet an embrace of the bitter-sweet concept does not only bring meaning to theists, but also imparts purpose to the atheist who has made self-actualization his life’s goal. Through it he can come to see hardships as the classrooms of self-knowledge, opportunities to prove himself and grow as a man, vital training on the path to becoming superhuman.

Finding Meaning in Suffering

“If there is a meaning in life at all, then there must be a meaning in suffering. Suffering is an ineradicable part of life, even as fate and death. Without suffering and death human life cannot be complete.

The way in which a man accepts his fate and all the suffering it entails, the way in which he takes up his cross, gives him ample opportunity — even under the most difficult circumstances — to add a deeper meaning to his life. It may remain brave, dignified and unselfish. Or in the bitter fight for self-preservation he may forget his human dignity and become no more than an animal. Here lies the chance for a man either to make use of or to forgo the opportunities of attaining the moral values that a difficult situation may afford him. And this decides whether he is worthy of his sufferings or not.” -Viktor Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning

Of course when we’re in the midst of a trial and the trough of heartache, it is difficult to joyously glory in the figurative blood flowing over our breastplates. But when challenges do come, an embrace of the bitter-sweet concept can at least keep you from cursing God or sliding into an existential funk. You can find meaning in your suffering when you understand that there can be no pleasure without pain, and come to view your hardships as tests–opportunities to prove your mettle; it is easy to live with virtue and dignity in good times, but how will you act when the storms come? Will you fall apart or hold steady?

And even if the knowledge that you cannot have the sweet without the bitter doesn’t prevent you from slipping into despair during your darkest hour, it can allow you to find meaning in your suffering once the passage of time dissipates your anger and grief and gives you the distance necessary to ponder the ways in which the hardship has strengthened you, and left you better prepared to meet your next challenge. But only, of course, if you let it.