Welcome back to our series on the history of the American bachelor. Last time we discussed the bachelor in colonial and Revolutionary War America where we learned about his origins as well as the laws and taxes levied specifically against single men. Today we turn our focus to the state of the American bachelor after the Civil War.

Post-Civil War America: The Golden Age of the American Bachelor

As urbanization and industrialization began to take off in the first half of the 19th century, thousands of young, single men migrated from farms to cities. The large immigration of European men, particularly from Ireland, only added to the growing pool of urban bachelors in antebellum America; in some cities bachelors made up more than 50% of the male population.

The bachelor population in urban areas only grew faster after the Civil War. Consequently, single men often greatly outnumbered single women in the cities. This gender imbalance, along with the rising costs of living, resulted in young men putting off marriage longer than previous generations of bachelors. By 1890, the average marrying age for a man was close to our modern marrying age: 26. With so many men putting off marriage, a feedback loop formed that increased the proportion of urban single men even more. In that same year, the U.S. Census Bureau estimated that 67 percent of all men between the ages of 15 and 34 were bachelors.

Despite the devastating loss of tens of thousands of young, single men during the Civil War, the bachelor became a demographic force to be reckoned with in the closing decades of the 19th century. With so many bachelors living close together in cities, an entire bachelor sub-culture formed that would fuel new businesses and industries and shape America’s conception of masculinity in the 20th century. Indeed, the period between the Civil War and World War I became the golden age of the American bachelor.

Living Arrangements of Urban Bachelors

Five Points, NYC

The thousands of young, single men who flowed into cities tended to congregate together as they set up a new life for themselves. Many large cities developed unofficial districts that contained a large number of unmarried, working class men. Working class bachelors lived, labored, and relaxed in these “Bachelor Districts.” If you’ve seen Gangs of New York, the Five Points neighborhood where the movie takes place is a good representation of these late 19th century Bachelor Districts–dirty, lawless, and crowded.

To house all these unmarried men, boarding houses were built. For a dollar or just a few cents a week, a young bachelor could have a bed to sleep in and (maybe) a place to bathe. Boarding houses varied in their amenities and comforts. Most boarding houses in the working class districts were dirty and provided no privacy. Men were forced to share a small room with five or sometimes ten other men. Sharing beds with complete strangers wasn’t uncommon, nor was choosing to share a bed with a friend to save money. Middle class bachelors could usually afford more refined boarding. For a few extra dollars a week, a man could get a room to himself that included a dresser, a rug (hot dog!), and daily hot water for shaving.

The atmosphere of these boarding houses in many ways resembled that of the modern day frat house. Young men living alone in the cities found companionship and camaraderie with their fellow residents. Jokes, ribbing, and social drinking were all part of the experience.

Despite the boarding house boom in post-Civil War America, most bachelors lived with their parents or a next of kin. In 1860, 60 percent of native born unmarried men between the ages of 15 and 30 lived with family. Chances were your great-grandpappy lived with his parents well into adulthood (the idea that living at home past age 18 is an unprecedented modern problem and represents a failure on the part of contemporary young people is a myth based on comparisons to the unique circumstances in post-WWII America…but we’ll save that discussion for another day).

Socioeconomic factors played a significant role in whether a bachelor lived with family or by himself. Working class bachelors were more likely to live with their families than their middle-class counterparts, simply because their blue collar brethren couldn’t afford to pay for boarding elsewhere.

Bachelor Hangouts

Like the 17th century bachelors at Harvard who founded “The Friday Association of Bachelors,” bachelors in post-Civil War America began forming groups to cater specifically to their unique needs. Enterprising businessmen also saw an opportunity to make a buck off this growing demographic and so created businesses to accommodate the burgeoning bachelor population.

As mentioned above, middle-class bachelors were more likely than their working class peers to break away from the constraints of family life and try to live on their own. But in the absence of mom, dad, and six siblings, these men still craved company and companionship, and middle class urban bachelors would often recreate family life with other single men in private men’s clubs. Most major cities at the turn of the 20th century had one of these clubs, places where a young bachelor could share the expenses of rent, meals, and a housekeeper. The clubs were somewhat like working class boarding houses, only a whole lot nicer.

Private men’s clubs were often built in elite parts of towns and were decorated with dark wood walls and banisters, red carpets, and masculine art. The clubs usually had a study or sitting room where a young bachelor could sit, read, and take part in stimulating conversation over cigars and drinks. A billiards table was a common piece of furniture. Married men would even join a private men’s club just so they could have a place to retreat to when they wanted to get away from the family. Some of these clubs included the Olympic Club in San Francisco, Boston’s Somerest Club, and New York’s Knickerbocker Club.

Private men’s clubs weren’t without their critics. Many saw them as a direct threat to the future of the American family. Why would a young man want to get married when he had all the benefits of family in his club? New York journalist Junius Henri Browne said this of the clubs: “Every club is a blow against marriage… offering as it does, the surrounding of a home without women or the ties of a family.”

In addition to private clubs, other bachelor hangouts included fraternal lodges like Freemasons and the Odd Fellows. From 1870 to 1920, growth in fraternal organizations boomed. According to Understanding Manhood in America, by 1920 thirty million men were members of a fraternal organization. The lodge often served as a second home for men, both single and married. This mixture of married men and bachelors allowed for some symbiotic relationships. The older, married men often provided mentoring and advice to the younger, single men on transitioning into manhood, while the bachelors provided an atmosphere where married men could loosen their collars and enjoy some freewheeling and virile camaraderie.

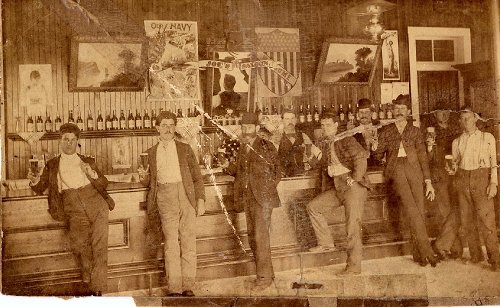

The golden age of the bachelor was also the golden age of the saloon. By 1895, American cities had, on average, one saloon for every 317 residents and the primary customer was single men (women, who were not prostitutes, were typically banned outright). For many bachelors living in cities, the saloon wasn’t just a place where they could grab a pint of beer and play cards with friends after work. Saloons also provided other services that bachelors needed, including banking services (like check cashing and credit extension) and mail services.

The most important service saloons offered bachelors was providing food. Back in the late 19th century, many cities required bars and saloons to provide free food to patrons. For just the cost of a pint of beer, a young and hungry bachelor could fill himself with some hearty victuals. For many urban bachelors, saloon food was their only source of sustenance. Immigrant Oscar Ameringer described the kind of free food you could get in an 1880s Cincinnati bar: “By investing five cents in a schooner of beer and holding on to the evidence of purchase, one could eat one’s fill of such delicacies as rye bread, cheese, hams, sausage, pickled and smoked herring, sardines, onions, radishes, and pumpernickel.”

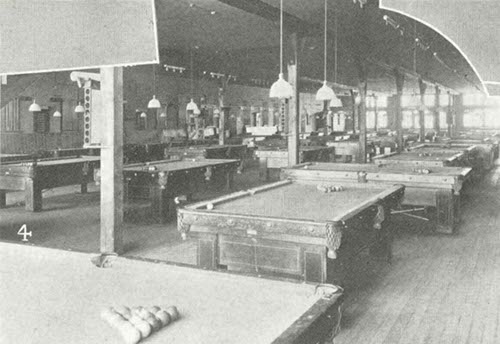

Billiard halls sprung up like weeds in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as well, and bachelors were their primary clientele. Popularly referred to as a “young man’s game,” pool was a way for bachelors to blow off some steam after work and maybe even make a little money gambling. The pool hall became a place that ushered working class boys into the world of adult male society. Legendary pool champion Wimpy Lassiter looked back nostalgically at his youth in the early 20th century and said this about pool halls:

“A long time ago I used to stand there and peek over the lattice work into that cool-looking darkness of the City Billiards in Elizabeth, North Carolina… And it seemed as though the place had a special sort of smell to it that you could breathe. Like old green felt tables and brass spittoons and those dark polished woods. Then a bluish haze of smoke and sweet pool chalk, and strongest of all, a kind of manliness.”

Last, but not least, the barbershop was another important hangout for bachelors between 1860 and 1920. In Chicago, the number of barbershops shot up from 308 in 1880 to nearly 2,000 by 1896.

It’s no coincidence that the golden age of the barbershop occurred simultaneously with the golden age of the bachelor. Before men moved from the farm to work in factories and offices in the cities, they usually got their hair cut by another family member. Living alone in the city, a bachelor needed somebody else to do it for him. Also, because single men typically lived in a room that lacked the basin and hot water needed for a comfortable shave, they would often head to the barber once a week to get their scruff removed.

Barbers also provided other essential services for bachelors, specifically medical and dental care. Old barbering books from the late 19th and early 20th centuries often provided recipes for creams and tonics to cure ringworm and other skin diseases. There were even recipes for barber-made cough drops.

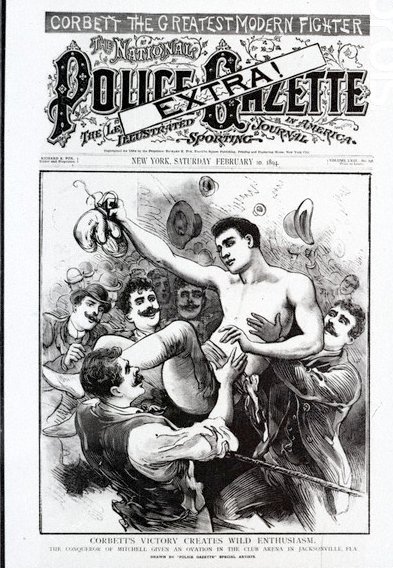

Cover of National Police Gazette Magazine

Barbershops also served as news centers and civic forums for men. Men would frequently drop by the barbershop just to see what was going on and chew the fat with other men. Barbers kept their shops well-stocked with magazines and newspapers for their clients to read while they waited for a shave. The most popular magazine among single men in the late 19th century was The National Police Gazette, a weekly periodical where a man could get the latest updates about boxing matches and read tawdry crime stories. Due to the popularity of The National Police Gazette among barbers, the magazine had a weekly feature called “Tonsorial Artist of the Week” where they highlighted the work of a singular barber. The National Police Gazette laid the foundation for the versatile men’s lifestyle magazines we enjoy today (including, the Art of Manliness!).

Like private men’s clubs, bachelor hangouts were criticized by moralists and newspaper editors. Saloons and pool halls received the brunt of the criticism. The Georgia Anti-Poolroom League (yes, there were organizations that quaintly fought poolrooms) argued that poolrooms “diverted man power” and encouraged “idleness…dissipation…intoxicants…profanity…lascivious stories…and the love of chance.” In New York City, moralists denounced the Henry Hill saloon as the “most dangerous and demoralizing place in New York.”

Not only did saloons and pool halls encourage the obvious vices like drunkenness and gambling, critics argued, they distracted young men from taking on the responsibilities of adult life as well. Echoing Benjamin Franklin’s criticisms of bachelors in Revolutionary America, 19th and early 20th century critics believed that the illicit activities engaged in in these establishments sapped young men of their vim and vigor. Bachelor hangouts were a threat to American manhood and America herself.

The Sporting Male

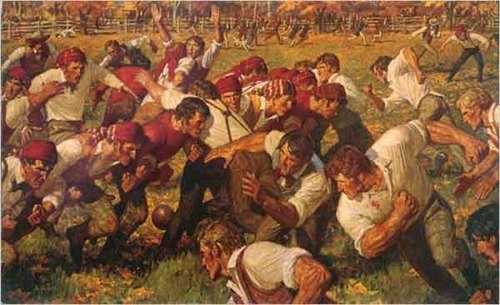

First American Football Game. Rutgers v. Princeton. Painting by Arnold Friberg

Many young men living at the turn of the century had a bit of anxiety about their masculinity in comparison with their ancestors. With no more frontier to settle or wars to fight, how would they prove their mettle? Would their virility ebb away as they sat at desks or worked in factories instead of tilling the land or hammering at a forge?

The sports arena became a substitute “frontier” and “battlefield” where young men could display their masculine strength and competitive drive. It was during the late 19th century that many of the popular sports we enjoy today got their start. Bachelors had a major influence on the rapid rise of sports in American culture. Many of the first organized baseball, basketball, and football teams were formed among bachelors attending college. Christian churches embraced the country’s new love of sports in the hopes of making church more attractive to men, particularly young, single men during the Muscular Christianity movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Of all athletics, boxing was seen as the most virile sport a man could take part in. Even if a man didn’t actually step in the ring to fight, he’d spend his weekends watching two other fighters duke it out in matches that lasted hours and sometimes days. During the golden age of the bachelor, boxing was the most popular spectator sport.

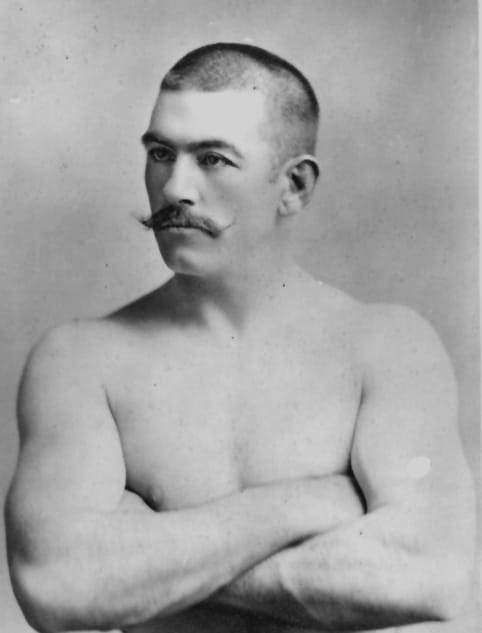

John L. Sullivan. Hero to Bachelors.

Boxing also gave birth to America’s first national sport’s hero, John L. Sullivan. In many ways, Sullivan was the paragon of this period’s ideal of virile bachelorhood. Though he was married, John L. lived the life of a bachelor for most of his life: drinking, fighting, and carousing with other women. He spent more time at the saloon with other bachelors than he did with his family.

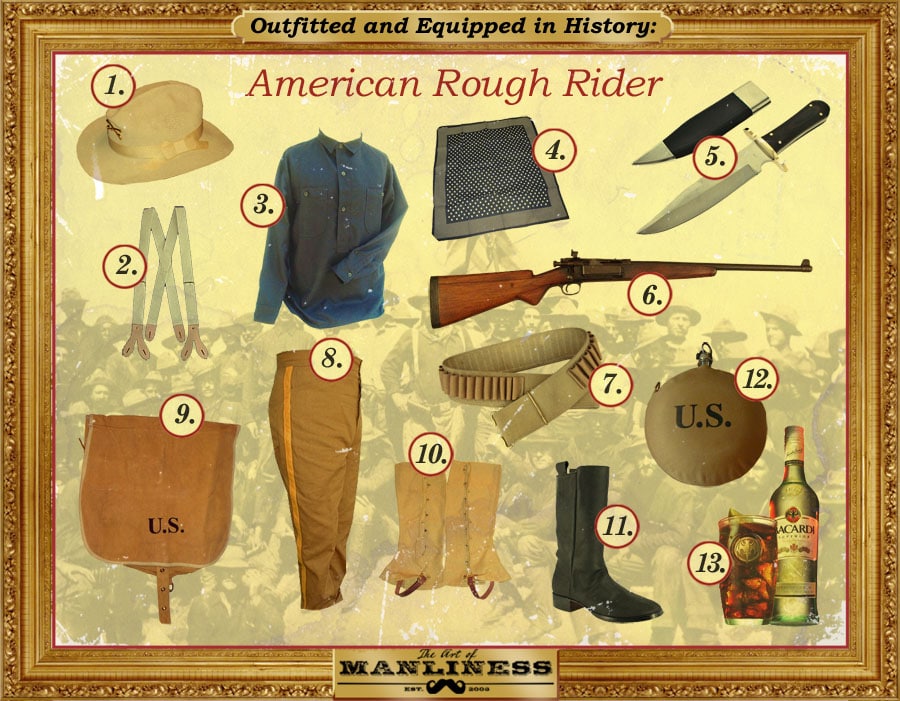

In addition to athletics and competition, men, especially working class bachelors, began to define their manliness by their patronage of “illicit” pastimes and vices like drinking, pool games, horse racing, pugilism, card games, cigar smoking, and cock/dog fighting. This “sporting male” identity is still with us today in many ways from the benign weekly poker nights to the more depraved binge drinking rituals in college fraternities.

Thus the golden age of the bachelor was a time where young, single men, free from the responsibilities of family life and laws that targeted their demographic, enjoyed an unprecedented amount of freedom and male camaraderie. And yet this kind of freedom still created a tension in society–what if men enjoyed bachelorhood so much that they never wanted to settle down? This tension between the enjoyment of bachelor culture by some, and the worry that it was too enjoyable by others, continued into the 20th century. And to that time period we will turn in our next and final installment on the history of the bachelor in America.

History of the American Bachelor Series:

Colonial and Revolutionary America

Post-Civil War America

The 20th and 21st Century

____________________

Sources:

Citizen Bachelor by John Gilbert McCurdy

The Age of the Bachelor by Howard P. Chudacoff