Many of you who read the Art of Manliness are bachelors. And if you’re married, well, you were a bachelor once, too. Bachelorhood has become such an ingrained part of the male experience, that we usually don’t give it too much thought except to make jokes about bachelor pads or married men “batching it” when their wives are out of town.

While it might not seem so at first blush, the history of the bachelor in America is complex and truly fascinating. When colonists first settled America, the bachelor as an identity didn’t even exist. But as time passed, bachelors became one of the driving forces in shaping our concept of manliness. In fact, many of the popular ideas we have about manliness today (and that we talk about on the site), emerged out of bachelor culture.

What’s also interesting is that the discussions we’re having about the state of young, single men today are very similar to the discussions our colonial, post-Civil War, and WWII ancestors had as well. As you study the evolution of the bachelor, you’ll see that throughout our country’s history, Americans have had conflicting views about single men. On the one hand, we’ve seen them as a threat to good society and stigmatized bachelors for not conforming to traditional family life by putting off marriage. On the other hand, Americans have celebrated bachelors as paragons of American individualism and independence and envied their freedom.

Over the next few weeks, we’ll be exploring the history of single men in America. Understanding the history of bachelorhood in America will hopefully provide some insights to you on manliness today. Even if that doesn’t happen, it’s just an interesting part of history to know!

Bachelors as Dependents

Up until the 17th century, single men weren’t viewed as a distinct social group. Instead, they were lumped together with women, children, and servants. The English, and subsequently American colonists, didn’t even have a name for young, single men. It wasn’t until the 17th century that colonists started using the term “bachelor” to describe a single man.

However, the word bachelor wasn’t used in the same way as we use the word today. For Colonial Americans, bachelorhood wasn’t solely dependent on your marriage status like it is for us modern folks. You could be a single man, but not be considered a bachelor. Instead, bachelorhood was dependent on a man’s age and whether he owned property.

Colonial Americans, particularly New England colonists, divided men into two groups: masters and dependents. When early American settlers referred to a man as “master” they weren’t necessarily indicating that the man owned slaves. Rather, the status of master meant a man had attained sufficient mastery over himself and in his vocation that he was able to own property and contribute to the community in a significant way. It also meant you were older, perhaps in your 30s or 40s. As we’ll discuss shortly, bachelors were subject to special laws, and there are plenty of examples from early New England settlements where single men who were considered masters, sat on judicial councils that punished other single men for being bachelors.

In contrast to masters, dependents were young, single men who lacked private property and held no responsibilities within the community. These sorts of men held the same position in society as women, children, and servants. Their lack of mastery actually prevented them from being considered men. When writers of the 16th and 17th centuries referred to bachelors, they meant dependent men.

“The plantation can never florish till families be planted and the respect of wives and children fix the people on the soil.” -Sir Edwin Sandy, Treasurer Virginia Company of London, 1620

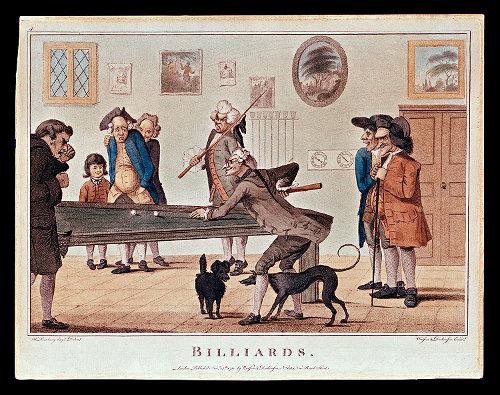

17th century New England colonists didn’t take too kindly to bachelors. They saw them as a threat to wholesome society and prone to hooliganism; pamphlets printed at the time referred to bachelors as “rogue elephants.” Life in the early colonies was so precarious that cajoling as many members as possible into producing for and contributing to the colony was essential to survival. It was feared that without the stabilizing, civilizing effect thought to be imparted by taking on the responsibility of wife and kids, bachelors would refuse to settle down and would run amok and turn to dabbling in unholy vices. So to combat the bachelor menace, many of the colonies in New England created what were called “Family Rule” laws that required young, single men to continue living with their family until they had established themselves and were married. If a man didn’t have family nearby, he could board with another family. Violators faced stiff fines and even jail time. Despite the draconian laws, some bachelors had the chutzpah to flaunt convention and risk punishment by living alone.

Towards a More Accepted Notion of Bachelorhood

Towards the end of the 1600s, Family Rule laws in New England started to relax and more and more young, single men started living by themselves. While New England communities still frowned on the practice, they didn’t go out of their way to prosecute bachelors for living on their own. The number of bachelors grew to such an extent that Harvard students formed the first bachelor club in 1677 called the “Friday Evening Association of Bachelors.” The organization was dedicated to the “Promotion of Good Morals and Good Citizenship.” Meetings were held on, you guessed it, Friday night and consisted of lectures from local ministers or a reading of a paper written by a member. The goal was to help these young bachelors temper their base desires and passions and eventually become masters, and consequently men.

What’s interesting about early American ideas of bachelorhood was the dichotomy between the respective views of the New England and Chesapeake Bay colonies. While the Puritan New Englanders wrung their hands about young, single men and created laws that essentially outlawed bachelors, in the Chesapeake colonies, where men outnumbered women to a far greater extent than up North, the society was much more accepting of them. Rather than making bachelorhood a pejorative status to designate young, single men as dependent and useless, bachelorhood in the South was conferred upon any unmarried man, whether he owned property or not. This idea of the bachelor would eventually spread to New England and become the definition of bachelorhood that we’re familiar with today.

Bachelor Taxes and Forced Military Duty

Even as early Americans began recognizing single men as a distinct and autonomous group, worry and suspicion over bachelors continued. Bachelors seemed so untamed, rough, and ill-suited for contributing to civilized society. So starting in the 18th century, American colonists once again started creating laws that singled out bachelors and punished single men for being unattached.

Inspired by the ancient Greeks, colonies started to levy “bachelor taxes” on men who remained unmarried after a certain age. The idea was that because single men didn’t have a family to support, they could afford to contribute more money in taxes. The tax served two purposes besides filling the colonial coffers. First, it reduced the amount of disposable income bachelors had to use on bachelor indulgences like boozing, gambling, and whoring. Second, the tax acted as an incentive for young men to quit dragging their feet on the way to the altar and settle down.

Bachelor taxes were just the beginning of the 18th century’s legal war against single men. Many colonies imposed higher fines on bachelors than on married men for similar infractions. So if you (a bachelor) and that lawfully married Mr. Smith were both caught playing hooky from church one Sunday (a legal infraction in many colonies), the authorities would take it easy on Mr. Smith while hitting you with the full fine because, well, Mr. Smith has seven mouths to feed at home, while you just spend your money on ale.

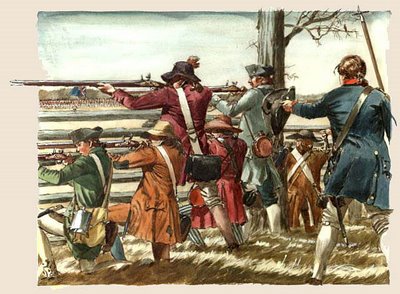

Colonies also passed laws that required mandatory military service from single men, while excusing married men from such obligations. Just as the early joint stock companies had seen single men as a disposable resource who could be used to tame the American wilderness in preparation for the arrival of women and families, the lives of bachelors were seen as easier to spare for sacrifice on the battlefield.

Now, American bachelors didn’t sit idly by while a bunch of married men passed taxes and laws that punished them for simply staying stag. No, the bachelors of America united to fight bachelor laws. Letters were published in newspapers and pamphlets were passed around arguing that laws singling out young bachelors were undemocratic and immoral. Many historians call the fight against bachelor laws America’s first civil rights movement. The bachelors’ work paid off. By the end of the Revolutionary War, bachelor laws in all the colonies had been repealed.

Bachelor as Threat to Republican Manhood

Despite the growing acceptance of bachelorhood, many leaders during the American Revolution saw bachelors as a threat to republican manhood. One of the most vocal and ardent critics of bachelors was Philadelphia publisher and statesman, Benjamin Franklin. Franklin wholeheartedly believed that bachelors were “but one half of a pair of scissors,” and that “a single man has not nearly the value he would have in a state of union. He is an incomplete animal.” He used his newspapers and his other publications as a bully pulpit from which to sound the warning about the threat of young bachelors. Franklin saw bachelors as weak-willed, indecisive, and selfish men who were more attracted to living a luxurious life than helping build the young republic. In his Poor Richard’s Almanac, Franklin often portrayed bachelors as effeminate, European-loving dandies who lacked the hardihood that American masculinity required in order to settle a new country.

The great irony about Franklin’s disdain towards bachelors was that technically, Franklin himself was a bachelor for most of his life. He never formally married his wife Deborah Read because she was unable to secure a divorce from her first husband, John Rodgers. They were forced to establish a common-law marriage. Moreover, as a young man, Franklin had indulged in the behaviors he abhorred in bachelors and fathered a son out of wedlock. And he spent many years in Europe away from Read, often choosing to prolong his stay and continue functionally living as a bachelor himself, flirting with the French ladies who couldn’t get enough of Franklin’s gout-y charm, even though his wife was lonely.

Old Ben’s war against bachelors was in vain though. Americans were becoming more and more accepting of bachelorhood. In fact, at the start of the 19th century, many began to see a man’s bachelor years as a formative time in a young man’s maturation, a time where he laid the foundation for the rest of his adult life. It was during a man’s bachelor years that he’d gain an education, establish a career, and find a woman with whom he could settle down. Instead of being viewed as “rogue elephants,” Americans began to see bachelors as symbols of manly independence and strength.

Next time: The Golden Age of the American Bachelor, 1860-1900

History of the American Bachelor Series:

Colonial and Revolutionary America

Post-Civil War America

The 20th and 21st Century

____________________

Sources:

Citizen Bachelor by John Gilbert McCurdy

The Age of the Bachelor by Howard P. Chudacoff

The above are the only two comprehensive books written about the history of bachelorhood in America. I highly recommend picking up these books if this topic interests you. Very fascinating reads!