The question of how to choose a camp stove sometimes ends up being a discussion with the rancor of a religious debate. Ultralighters, basecampers, and everyone in-between has an opinion. So let’s explore the different options, and maybe we can come to an ecumenical agreement.

There are many stoves on the market, and almost all have unique features that give them their niche. Ultra-light, ultra-small, ultra-blowtorch: they all have functions that serve a certain kind of purpose on a certain kind of trip. The “best” stove is the one that’s best for you, when it’s best for you.

Stoves are usually divided up into two main categories: liquid fuel stoves and canister stoves. They are often further divided into basecamp and portable stoves. Let’s take a look at some of the features and drawbacks of the various stoves in each grouping.

Basecamp Liquid Stoves and Canister Stoves

Advantages: Higher heat output. Pot stability. Capacity for larger pots.

Disadvantages: Bulky and heavy. For canister stoves, the heat costs a little more.

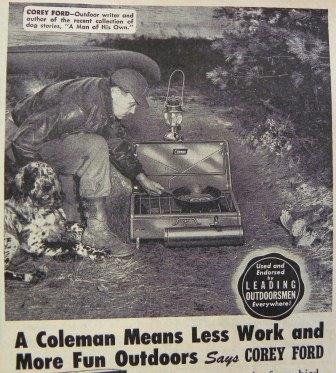

I lumped the basecamp stoves into one category as they are more or less identical in their functions. These are the large, two-burner (or three) stoves you recognize from when you were a youth. They’re big, they put out a lot of heat, and they’re great for recreating conditions that rival the home kitchen. In fact, we’ve been known to use our nostalgically green body with red tank Coleman two-burner for cooking french fries on the porch to keep the kitchen from becoming a franchise of McDonald’s with all the attending grease and none of the profit.

I also have a flat propane-fueled basecamp stove that fits nicely into spots where the Coleman would be a squeeze. It doesn’t throw off the BTUs of a Coleman, but it’s quiet, clean, and quite a bit lighter. So what if your coffee takes eight minutes instead of six? You’re outside, enjoying a lovely view, not at Starbucks.

The benefits of basecamp stoves are obvious: more heat and more stability. If you can cook in a kitchen, you can cook on a basecamp stove. But what they gain in convenience, they lose in portability. Take one backpacking? Nope. How about on a canoe or kayak trip? A canoe trip, perhaps, especially if you’re not portaging and if you’re cooking for a very large group (over a dozen or so). A kayak trip, well, they’re probably not going to fit through the hatches. Oh well.

Portable Stoves

Liquid-fueled

Advantages: Best cost to heat ratio. Good for air travel (if stove is clean). Perform well in cold weather. Option to burn multiple fuels. Usually field-serviceable.

Disadvantages: Can be fussy and require priming to start. Possibility of pollution is higher.

These are common and popular, as they can travel all over the world, many burning whatever fuel they come across. They are lightweight and portable, sometimes stowing inside your cook kit to save space. They are relatively simple little contraptions, so they are long-lived and usually field-serviceable. They are considerably less expensive per BTU as liquid fuel doesn’t come in canisters.

However, liquid-fueled stoves have downsides. They are less convenient, as they usually require priming and can do a lot of flaring up before they settle down to business. They can be somewhat noisy, like my old Svea 123 that I’ve had for decades, but it’s a nice little putter, which I am told sounds like a very small V1 rocket. Probably not very comforting to someone who lived through WWII in London, but I like it.

Many of these stoves have interchangeable jets that allow you to use different fuels such as automotive fuel or kerosene. If you don’t change the jet, they’ll smoke like an Italian movie star and eventually clog until they’re cleaned out.

If you are considering air travel, your stove must be whistle-clean. A friend of mine who went backpacking in Tibet wanted to take his stove with him but was having trouble getting it clean enough for the airlines. I told him something like, “Look dude. If you can afford airline tickets to Kathmandu, you can afford a new stove. Make sure it burns kerosene and donate it to the locals when you come home.”

The biggest disadvantage is pollution—a very small amount of white gas or kerosene can pollute a lot of water (10,000 gallons according to the Leave No Trace people), so if you’re filling your stove on a sandbar and you spill a few tablespoons of fuel, you’ve just polluted thousands of gallons of water. It doesn’t mean you shouldn’t use liquid fuel stoves, they just require more care.

The Trangia Methanol Stove

Advantages: Simple. Safe. Dead quiet. Use non-petroleum based fuel.

Disadvantages: Lower heat output. Less control over heat. Fuel is less convenient and can melt your Swiss Army Knife handle.

There is one liquid stove that isn’t conventional, for fuel or for function: the Trangia stove. A Swedish stove that burns methanol, also known as wood alcohol, it’s very fuel-efficient. The Trangia is very stable and self-contained and can be used safely in areas where a gas stove may not work. It functions by burning alcohol in a small wicked cup, sort of like a Sterno but with more efficiency. It has one small vice, and that is it can take two to three times longer to boil water, as methanol is not loaded with the BTUs that you find in white gas or kerosene. That said, you just have to alter your camp set-up routine—get out the stove and light it up, and when you’re done setting up your tent, you’ve got your water boiling.

There is one liquid stove that isn’t conventional, for fuel or for function: the Trangia stove. A Swedish stove that burns methanol, also known as wood alcohol, it’s very fuel-efficient. The Trangia is very stable and self-contained and can be used safely in areas where a gas stove may not work. It functions by burning alcohol in a small wicked cup, sort of like a Sterno but with more efficiency. It has one small vice, and that is it can take two to three times longer to boil water, as methanol is not loaded with the BTUs that you find in white gas or kerosene. That said, you just have to alter your camp set-up routine—get out the stove and light it up, and when you’re done setting up your tent, you’ve got your water boiling.

Fuel is usually obtained at a pharmacy if you want the highest quality methanol. If you have a friend who’s a chemist at the local college, even better. However, the methanol is tough on plastic. Spill it on some plastics and they melt or at least get very sticky.

Fuel is usually obtained at a pharmacy if you want the highest quality methanol. If you have a friend who’s a chemist at the local college, even better. However, the methanol is tough on plastic. Spill it on some plastics and they melt or at least get very sticky.

The nicest thing about the Trangia stove is its quiet nature. Sitting on a sand bar on the Wisconsin River, I’ve heard herons hunting frogs in the shallows a hundred yards away, and the only sign of a boiling kettle was the lid rattling when the water was ready for tea. That’s nice. And since methanol is a wood alcohol, it’s a renewable resource. Bueno.

The nicest thing about the Trangia stove is its quiet nature. Sitting on a sand bar on the Wisconsin River, I’ve heard herons hunting frogs in the shallows a hundred yards away, and the only sign of a boiling kettle was the lid rattling when the water was ready for tea. That’s nice. And since methanol is a wood alcohol, it’s a renewable resource. Bueno.

Canister Stoves

Advantages: Smaller. Super-convenient. Lightweight. No priming or flare-ups. Best control of heat for baking, simmering, or frying.

Disadvantages: Fuel is more costly and less available. Canisters must be packed out and you can’t fly with them. Less performance in colder temperatures.

These little beasts have really come into their own in the last few years. Ultralight freaks and backpackers drool at the tiny little titanium stoves from manufacturers such as MSR, Primus, Snowpeak, etc. They’re fast and easy to use, setting up in moments and burning seconds later.

These stoves are more popular now as the fuel mixture has been altered, using a hotter-burning propane-butane combination. They light more easily, and they work better at colder temperatures than the old straight butane stoves.

The downsides are considerable for the traveler. Compressed gas cannot be transported on aircraft. If you try to sneak them through the checked baggage, prepare for a very hefty fine and a visit to the little windowless room at the airport. No kidding. And it’s a dumb idea anyway. Also, finding the proper canisters when you arrive at your destination can be tricky. If you’re driving, no problem. If you’re flying, problem.

They’re also expensive to operate over a long trip. If all you do is boil water, no worries: the cost differential is negligible. If you’re cooking beans and rice, that’s one expensive pot of flatulence. You also will have to pack out the canisters, which on a long wilderness trip is a consideration.

Other than that, they’re wonderful. A very controllable flame means cooking non-blackened eggs is possible. If you bake with one of the new stove-top ovens, then a canister stove is definitely worth its keep. They are also safer, especially if you’re cooking in your tent vestibule (not your tent).

So Which One Do I Buy?

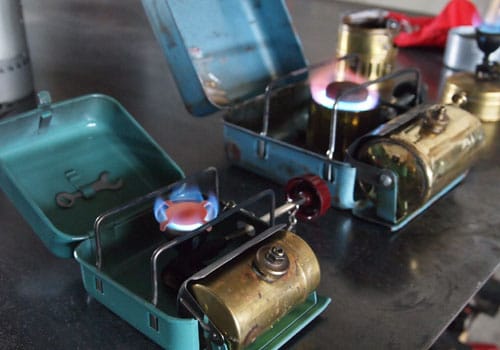

Ah, that’s not so easy. I have a bunch of stoves…an old Svea 123 (the pretty brass stove shown above that has served me since teenage years), an MSR Dragonfly liquid fuel stove for kayak camping, and a baby Snowpeak that I use for backpacking. My Trangia I use mostly for solo canoe trips where I want peace and quiet. I have an Optimus 111 that is a beast–the only portable stove that can boil a big pot of spaghetti for a group of eight without using a sundial to measure boil times. Then there are my collectibles brought back from a stove coma. They’re beautiful, and they work.

There aren’t really any bad answers, just compromises. Decide what you’re going to do first, and then choose a stove that matches your needs. Just like shoes, no size fits all, and people have more than one. If you’re going to start collecting things, you couldn’t do much worse than stoves, as they are relatively inexpensive and a lot of fun.

Advantages: Collecting stoves is a cheap hobby and a lot of fun.

Disadvantages: None that I can think of.

Years ago a friend of mine came over to the house for dinner, and we got to chatting about gear. Before too long the picnic table on the porch was humming, and the wives disappeared as the methanol, propane, and white gas flowed like whiskey. It was what my wife calls a CGM (Classic Guy Moment) when she overheard us discussing the virtues of priming paste vs. alcohol in a dropper bottle.

We ended up spending a few hours puttering around with different stoves, timing water boiling, and just enjoying the blue flames reflecting on the screens of the porch.

CGM, indeed.

P.S. Ultralight tablet-burning stoves are really cool and really light. I think they’re appropriate back-up stoves, but I consider them to be in a different class. Just my opinion. Your mileage my vary.