There are two kinds of freedom. Freedom from (negative freedom) and freedom to (positive freedom). The splitting of freedom into this binary framework can be traced at least back to Kant, was articulated by Erich Fromm in his 1941 work, Escape from Freedom, made famous by Isaiah Berlin’s 1958 essay, “Two Concepts of Liberty,” and explored more modernly by Charles Taylor.

These philosophers and thinkers generally used these two different categories of freedom to discuss and debate the role of government in citizens’ lives. But today we’d like to take a stab at exploring the way in which thinking about the difference between freedom from and freedom to can help us understand more about our personal development and the journey from boy to man.

Understanding the Difference Between Negative and Positive Freedom

Negative Freedom/Freedom From

Negative freedom is freedom from external interference that prevents you from doing what you want, when you want to do it. These restrictions are placed on you by other people. The more negative freedom you have, the less obstacles that exist between you and doing whatever it is you desire.

Charles Taylor calls negative freedom an “opportunity concept” of freedom because it gives you access to a range of desirable opportunities, regardless of whether you decide to take advantage of those opportunities or not.

The concept of negative freedom can be summed up as: “I am a slave to no man.”

Positive Freedom/Freedom To

Positive freedom is the freedom to control and direct one’s own life. Positive freedom allows a man to consciously make his own choices, create his own purpose, and shape his own life; he acts instead of being acted upon.

Taylor calls positive freedom an “exercise concept” of freedom because it involves discriminating between all possible opportunities, and exercising the options that are most in line with your real will and what you truly want in life.

The concept of positive freedom can be summed up as: “I am my own master.”

If the difference between negative and positive freedom still seems fuzzy in your head, the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy offers an excellent analogy to explain the nature of the two concepts.

Imagine a man driving a car. He comes to a crossroads. There is no traffic light, no police roadblock, and no other cars; the driver is free to turn whichever way he wants to, and he decides to turn left. This is negative freedom; the driver is free from restrictions which force him to go one way or the other. But what if the driver turned left because he needed to stop at a convenience store to get cigarettes, and he stopped even though it would mean missing an important appointment? It was his addiction that was really steering the car. This shows a lack of positive freedom; the driver lacked the freedom to do what he really wanted—to get to the appointment on time.

As the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy explains:

This story gives us two contrasting ways of thinking of liberty. On the one hand, one can think of liberty as the absence of obstacles external to the agent. You are free if no one is stopping you from doing whatever you might want to do. In the above story you appear, in this sense, to be free. On the other hand, one can think of liberty as the presence of control on the part of the agent. To be free, you must be self-determined, which is to say that you must be able to control your own destiny in your own interests. In the above story you appear, in this sense, to be unfree: you are not in control of your own destiny, as you are failing to control a passion that you yourself would rather be rid of and which is preventing you from realizing what you recognize to be your true interests. One might say that while on the first view liberty is simply about how many doors are open to the agent, on the second view it is more about going through the right doors for the right reasons.

Applying the Concepts of Negative and Positive Freedom to a Man’s Life

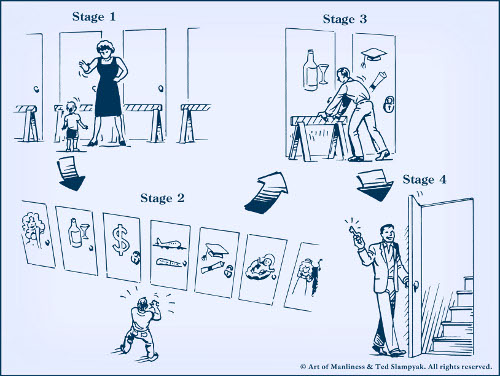

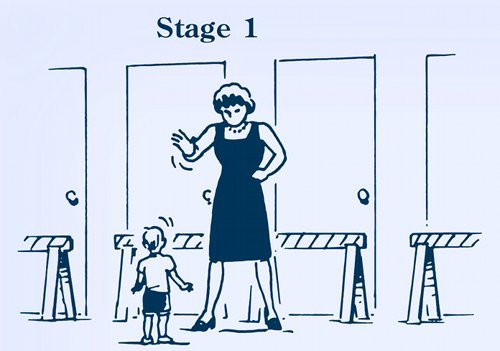

Stage 1: Childhood. Low negative freedom. Low positive freedom.

When you are a child, you are deficient in both negative and positive freedom. Your parents impose your schedule and the rules you must live by. Your possible choices are constrained, and your beliefs and goals often come from your parents. You also lack self-mastery; you have poor impulse-control and are afraid of a good many things.

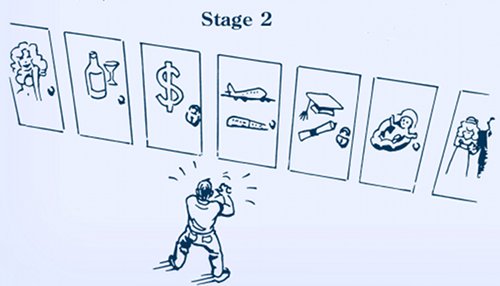

Stage 2: Young Adulthood. High negative freedom. Low positive freedom.

Then one day you turn 18, graduate from high school, and perhaps leave home and go off to college. For the first time in your life, there’s nobody looking over your shoulder telling you what to do. The external authority in your life is gone, and, especially in an Age of Anomie where there really aren’t any cultural rules anymore, you can do pretty much anything you’d like (short of violating the law). Party every night, sleep in to noon every day, skip class on a whim, bring whoever you’d like back to your place…

You’re awash in negative freedom—you have tons of opportunities, numerous doors to open. This is a pretty intoxicating feeling, and at first you revel in it, testing it out by pushing towards the old boundaries just to prove to yourself that they aren’t there. Strengthening your self-discipline and self-control is not a priority.

Note: Of course, freedom to do what you want doesn’t mean you’re free from the repercussions of those choices; you can still go broke and flunk out of school. You can choose your actions, but you can’t choose the consequences of those actions.

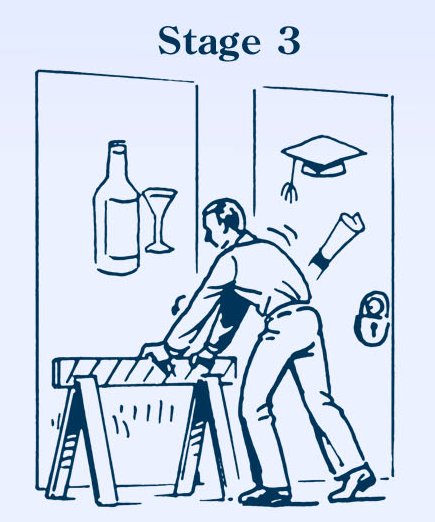

Stage 3: Emerging Adulthood. High negative freedom. Increasing positive freedom.

At a certain point, you begin to realize that while an infinite number of opportunities are open to you, not every opportunity is equal in importance. You go from thinking, “I can do whatever I want!” to “What do I really want out of life?” You begin to seek for greater meaning and to discover your life’s purpose. You find a higher level of desires for your life.

As your mindset changes, you start to discriminate between all the options open to you, deciding that some are more significant than others—those that lead to the fulfillment of your higher desires. As you examine the different doors before you, you notice that those that front your lower desires all swing open freely, and lead into a single room, while the doors that lead to your higher desires open to a staircase that takes you up a level to another hallway with a new set of doors. You also realize that some of the doors to your higher desires are locked. These locks represent internal obstacles keeping you from attaining what you really want in life. For example:

- You want to get married, but your shyness prevents you from talking to women.

- You want to graduate college, but your lack of discipline keeps you from studying and making passing grades.

- You want to complete an Ironman, but you’re fat and out of shape.

- You want to be financially independent, but you can’t control your spending.

- You want to live the tenets of your new faith, but you keep backsliding into old habits.

- You want to keep a job, but you can’t stop drinking and showing up hungover.

- You want to become a Congressman, but you have a fear of public speaking.

- You want to become a man, but you don’t know what that means.

You realize you have plenty of negative freedom–you’re free from external restrictions–but you don’t have much positive freedom, the ability to overcome fear, ignorance, and bad habits and traits in order to become the man you want to be.

Stage 4: Manhood. High negative freedom. High positive freedom.

While people are no longer imposing external restrictions on you, you decide that in order to become the man you want to be, you will have to come up with your own rules for yourself and set your own limits. You willingly work on developing your self-control, self-discipline, and willpower. In so doing, you gain the ability to control your lower desires in order to fulfill your higher desires. For example, the driver in the story above quits smoking, so that his addiction no longer controls his decisions.

Philosophers like Kant would say that these self-imposed restrictions do not decrease your overall negative freedom, because you have created the laws yourself, of your own free will and choice, and no man can enslave himself. Your negative freedom can only be constrained by others, who coerce you to do things contrary to your will. By learning to control and harness your desires, you actually become more autonomous. You’re not only free from external restrictions, but you are no longer a slave to your passions. You not only have the freedom of standing in a hallway of an infinite number of doors, you also have the freedom to step through any of them. Self-mastery is the master key that opens all doors.

The Pursuit of Positive Freedom and the Path to Manhood

Unfortunately, a lot of guys get stuck in Stage 2. They grow up in a culture that emphasizes negative freedom as the end all, be all of life; happiness=being able to do whatever you’d like. So they never make the transition from thinking about freedom from, to thinking about freedom to. But that transition is a big part of going from boy to man.

Men who shift from thinking exclusively about negative freedom to thinking about positive freedom as well discover that the restrictions they place on themselves do not limit their negative freedom–while their self-discipline does close off some possibilities, it opens new ones only available to those who have the positive freedom to grasp them. Almost any man can get a job; only a man with positive freedom can get his dream job. Almost any man can become a husband and a father; only a man with positive freedom can become a good husband and a good father.

On the other hand, men who do not mature past a singular focus on freedom from, see all restrictions, whether imposed by others or imposed by self, as limits on their negative freedom. If they discover that something they want is behind a locked door, instead of working on overcoming that inner obstacle, they shrug their shoulders and decide that they didn’t really want it anyway. For this reason, men who get stuck in Stage 2 make less progress in life and never reach the highest levels of “self-actualization,” superhuman-ness if you will.

Freedom from-dwellers also end up being restless and dissatisfied with their lives. Feeling in control of your life creates happiness and satisfaction, and feeling in control comes from gaining positive freedom from self-mastery. A man with positive freedom makes a strong connection between his purpose, what he has to give up to obtain that purpose, and the fact that he does so willingly. He understands the law of sacrifice, and takes ownership of and responsibility for his choices.

Finally, the advantage of cultivating a rich wellspring of positive freedom is that while a man’s negative freedom can be taken away by others, his reserve of positive freedom is an untouchable power source that can sustain him no matter how his external conditions change or what dire circumstances befall him.

This is precisely what psychiatrist Viktor Emil Frankl observed when he lived among his fellow prisoners–men who had been stripped of every vestige of their negative freedom–at the Nazis’ Theresienstadt concentration camp. As Frankl recounts in his famous book, Man’s Search for Meaning:

In spite of all the enforced physical and mental primitiveness of the life in a concentration camp, it was possible for spiritual life to deepen. Sensitive people who were used to a rich intellectual life may have suffered much pain (they were often of a delicate constitution), but the damage to their inner selves was less. They were able to retreat from their terrible surroundings to a life of inner riches and spiritual freedom. Only in this way can one explain the apparent paradox that some prisoners of a less hardy makeup often seemed to survive camp life better than did those of a robust nature…

The experiences of camp life show that man does have a choice of action. There were enough examples, often of a heroic nature, which proved that apathy could be overcome, irritability suppressed. Man can preserve a vestige of spiritual freedom, of independence of mind, even in such terrible conditions of psychic and physical stress.

We who lived, in concentration camps can remember the men who walked through the huts comforting others, giving away their last piece of bread. They may have been few in number, but they offer sufficient proof that everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms — to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.