The college football season starts this weekend, and I won’t lie—I’m pretty excited. My beloved Sooners are ranked number one in preseason polls, and I quite enjoy settling on the couch on a cozy fall day to watch them play (when they win at least!).

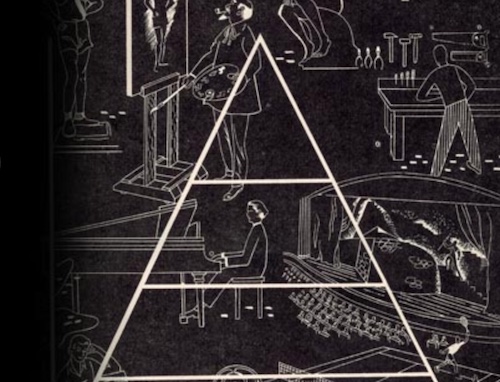

But every once in awhile, say when the announcer shares the game’s attendance numbers, I get a small niggling feeling of discomfort. 80,000 people gathered to watch 22 men run around, throw a ball, and smash into each other. The appeal is not difficult to see—there’s something truly compelling about watching the most talented athletes in the world perform. But when you take a step back, it’s really quite odd, isn’t it? Two groups of men–the doers and the viewers—and one group is far, far larger than the other.

The Rise of Spectatoritis

Here and there appears the aggravated case, completely infected, the fan who is nothing but a fan—a flabby creature, symbolic of the multitude, a parasite upon the play of others, the least athletic of all men, never playing himself at anything, a spectacle hunter, not a sportsman. –Richard Henry Edwards, 1915

During these odd moments I often think of an old book Kate picked up a few years ago at a used bookstore. Written in 1938 by Jay B. Nash, it’s entitled Spectatoritis. During the first half of the 20th century, leisure time had steadily increased, and Nash argued that because Americans had never before been confronted with such large swaths of it, the country had not developed a “philosophy of leisure.” Without this philosophy, people were falling victim to what he dubbed “spectatoritis:”

The machine age has, of course, already supplied an unexampled wealth of leisure and what happens? The average man who has time on his hands turns out to be a spectator, a watcher of somebody else, merely because that is the easiest thing. He becomes a victim of spectatoritis—a blanket description to cover all kinds of passive amusement, an entering into the handiest activity merely to escape boredom. Instead of expressing, he is willing to sit back and have his leisure time pursuits slapped on to him like mustard plasters—external, temporary, and, in the end, “dust in the mouth.”

Nash presciently predicted that the plague of spectatoritis would only increase:

Man can sleep too much. Granted freedom, many men go to sleep—“physically and mentally,” organically and cortically. Not having the drive for creative arts they turn to pre-digested pastimes, prepared in little packages at a dollar per. This has literally thrown us into the gladiatorial stage of Rome in which the number of participants becomes fewer and the size of the grandstands, larger. Spectatoritis has become almost synonymous with Americanism and the end is not yet. The stages will get small and the rows of seats will mount higher.”

One can easily see how the specter of spectatoritis has indeed seeped into all areas of our lives. Not only in the obvious things in which passive involvement has always been the norm–90 million Americans watched the 2011 Superbowl; 100,000 people watched U2 in concert in October—but in areas which were formerly forums of active participation. For example, in visiting a couple of “megachurches,” awhile back, I was surprised at how much the service (actually, they called it an “experience”—“service” sounds too boring and stodgy) resembled any other form of entertainment—people listened to the music, watched a video and powerpoint presentation, sat through a short message from the pastor, and left 60 minutes later. There were no requirements for participation or service of any kind. It was interesting to see that worship had become yet another thing to be passively consumed, as opposed to actively created.

A current trend in the building of new middle and upper class suburban homes is to include a “theater room,” a windowless room complete with large, movie theater-like chairs, a speaker system, and a big screen television. This is another one of those things that seems odd when you take a step back…a whole room in the house dedicated just to watching stuff. We’ve gone from having parlors for making conversation, to rumpus or recreation rooms for playing games, to rooms in which people sit silently side-by-side in the dark.

More than anything, the internet has contributed to the spread of spectatoritis. Online interactions are particularly insidious because they provide people with the feeling that they are actively participating in something, while in reality it is just another form of passive amusement. The main form of “activity” in modern life is the expression of personal preference. Liking or disliking. While formerly you could only be a fan of sports teams, you can now become a “fan” of Dominos Pizza, presidential candidates, even “sleeping.” I find it amusing that some websites have buttons in the response section of articles that allow people to upvote or downvote readers’ comments. So if you’re too lazy to write your own stuff, and it’s too much of a burden to even generate your own comment, you can still “participate” by showing your allegiance to someone else’s idea. But giving things thumbs up or thumbs down is not real participation. Why? Because such participation is “external, temporary, dust in the mouth.” Because it doesn’t involve any risk, any putting of your own skin in the game. Because it doesn’t change anything in you or in the world.

You Can’t Become a Man from the Sidelines

The personal interest in athletics has been largely superseded by an interest in spectacular games, which unfortunately tend to divide the Nation into two groups: the few overworked champions in the arena, and the great crowd, content to do nothing but sit on the benches and look on, while indulging their tastes for tobacco and alcohol.

It is this last that is turning so many thoughtful ones against baseball, football,etc. This, it will be seen, is a reproduction of the condition that ended in the fall of Rome. In her days of growth every man was a soldier; in the end a few great gladiators were in the arena, to be watched and applauded by the millions who personally knew nothing at all of fighting or heroism.

Degeneracy is the word.

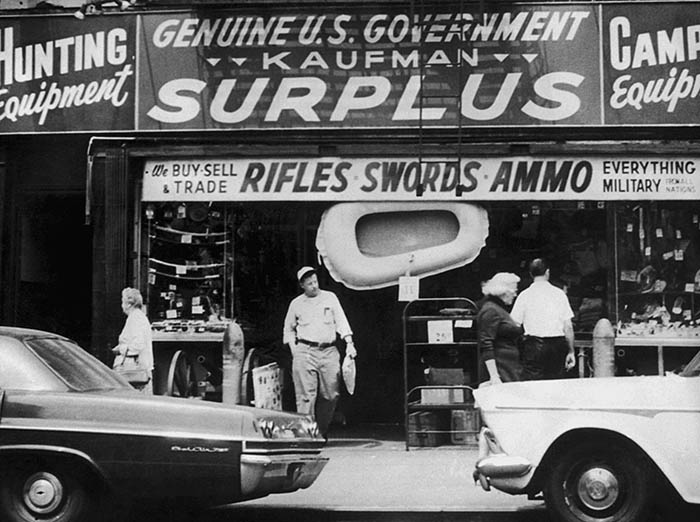

To combat the system that has turned such a large proportion of our robust, manly, self-reliant boyhood into a lot of flat-chested cigarette-smokers, with shaky nerves and doubtful vitality, I began the Woodcraft movement in America.” –Ernest Thompson Seton, creator of Woodcraft Indians, and a founder of Boy Scouts of America

Of course there’s nothing wrong with taking in a spectacle or two. As I said the beginning, I love to watch football, and I enjoy attending a minor league baseball game, movie, or concert from time to time. I do not currently have the privilege of enjoying the smug pleasure of telling people that I do not have a tv, and I enjoy catching a few shows each week. I like surfing the internet and sharing things on Facebook.

There are men who feel that the entire problem with males today is that they’re too obsessed with college and professional sports. But that’s as wrong-headed as thinking that indulging in a straight diet of passive entertainment carries no ill-effects whatsoever. Rather than suffering from spectatoritis, these men are inflicted by high-horse-itis.

No, a problem only arises when instead of being a supplement to your life—an occasional relaxing indulgence–passive amusements become a substitution, a way to feel better about something you personally lack.

Recently, William Deresiewicz wrote “An Empty Regard,” a searing op-ed piece for The New York Times in which he questioned our current unthinking idolization of the military. This near canonization of the troops began during the Iraq War with the well-intentioned purpose of not repeating the mistakes of Vietnam, in which opposition to the war translated into animosity to those serving in it.

Deresiewicz is not against supporting the troops per se—rather he argues that we use them as our “national football team,” as a reassuring symbol that the characteristics of traditional manhood are still alive and well. “The soldier is the way we want to see ourselves: stoic, powerful, focused, devoted,” Deresiewicz writes. But it’s a safe symbol—a team we can cheer for from the couch without having to step into the arena ourselves:

The greater the sacrifice that has fallen on one small group of people, the members of the military and their families, the more we have gone from supporting our troops to putting them on a pedestal. In the Second World War, everybody fought. Soldiers were not remote figures to most of us; they were us. Now, instead of sharing the burden, we sentimentalize it. It’s a lot easier to idealize the people who are fighting than it is to send your kid to join them. This is also a form of service, I suppose: lip service…

The political scientist Jonathan Weiler sees the cult of the uniform as a kind of citizenship-by-proxy. Soldiers and cops and firefighters, he argues, embody a notion of public service to which the rest of us are now no more than spectators. What we really need, in other words, is a swift kick in the pants.

And this is the real danger of spectatoritis run amok—it allows us to experience vicariously the virtues of others, without having to cultivate them ourselves.

We can see this phenomena in the popularity of certain television shows as well. Deadliest Catch. Ax Men. Ice Road Truckers. These programs showcase blue collar men working with their hands, getting dirty, and risking their lives to support their families. The white collar man, himself a stranger to manual labor, gets a vicarious dose of blue collar manhood by watching these shows, all from the comfort of his recliner.

But these vicarious experiences are fleeting. They conjure up feelings of manliness for an hour or two, but seep away, leaving the spectator entirely unchanged. And the world utterly the same.

Discussing a manly “philosophy of leisure” really deserves its own post, but for now, a simple recommendation is this: every man should have at least one thing in his life in which he has some skin in the game, in which he is actually in the arena, and not watching from the stands. One thing in which he is a doer, and not just a viewer.