I hope you’ve enjoyed our series on classical rhetoric. Today, for our final entry in the series, we will be discussing logical fallacies. This is a pretty important topic. Much of our debating has moved out of the public square and onto the internet. And if you spend anytime reading those online debates, you’ve probably seen how debased from the principles of classical rhetoric many of them are. Commenter X sets forth a fiery opinion on an article. Commenter Y responds by calling Commenter X a Giant Poopie Head for holding said opinion. And Commenter Z joins in with a tirade on a point that is not even argued in the piece.

For true civil and effective debate to take place, citizens must understand not only how to argue, but how not to argue as well. Every man should know how to avoid the pitfalls and traps of faulty arguing and how to recognize fallacies in the rhetoric of others as well.

What Are Fallacies?

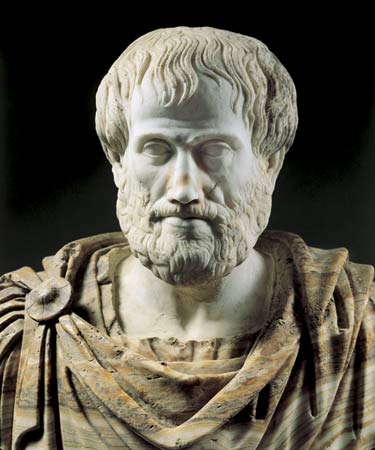

According to Aristotle in his treatise, The Art of Rhetoric, a speaker or writer has three ways to persuade his audience: ethos (appeal to the speaker’s character), pathos (appeal to emotion), and logos (appeal to logic). Aristotle believed that out of the three means of persuasion, logos was superior and that ideally all arguments should be won or lost on reason alone.

The problem with using logos as your sole means of persuasion is that it’s fraught with many opportunities for you to mess up and make errors in reasoning. These errors are called logical fallacies.

Just as there is formal and informal logic, there are formal and informal fallacies. Below we provide a quick intro to formal and informal fallacies and give examples from both.

Formal Logical Fallacies

Aristotle was a big fan of formal syllogisms. In fact, he wrote a whole treatise on them. There’s a reason why he liked them so much. Syllogisms are a powerful rhetorical tool. It’s hard to manipulate and argue against a formally laid out, sound syllogism.

A formal fallacy in syllogisms occurs whenever the structure of the argument itself is flawed and renders the argument invalid. The premises and conclusion of the argument might be true, but the argument can still be fallacious because the conclusion doesn’t follow from the premises. In my post about the three means of persuasion, I gave an example of an invalid syllogism:

All men are mortal.

Socrates is mortal.

Therefore, Socrates is a man.

At first blush, it looks like a decent argument. But read it carefully. Just because Socrates is mortal, doesn’t necessarily mean he’s a man. He could be a squirrel for all we know. This right here is an example of the fallacy of the undistributed middle. Let’s take a look at a couple of other formal syllogistic fallacies.

Affirmative conclusion from a negative premise:

No cats are dogs.

No dogs can purr.

Therefore all cats can purr.

Just because there aren’t any dogs that can purr doesn’t necessarily mean all cats can purr.

Negative conclusion from affirmative premises:

It’s impossible for a negative conclusion to be reached with affirmative premises.

All gods are immortal.

All immortals have beards.

Therefore, no gods have beards.

Informal Logical Fallacies

Informal fallacies are arguments that are fallacious for reasons other than a flaw in the structure of the argument. You’re probably familiar with a few informal fallacies already: red herrings, slippery slopes, etc. Below we list several of the most used informal fallacies to look out for when taking part in a debate.

- Red herring-an attempt to change the subject to divert attention from the original issue. You can see countless examples of this when you watch presidential candidates debate. Example: “Yes, I would absolutely make the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq a priority. But with the unemployment rate as high as it is, we really need to concentrate on domestic issues and creating jobs, and under my plan….”

- ad hominem– attacking the person instead of the argument. The goal is to discredit the argument by discrediting the person advocating the argument. Ad hominem attacks are popular in online discussions, especially when tempers flare. “Well, you’re wrong because you’re clearly an idiot!” That sort of blatant insult is easy to spot. Harder to detect are arguments that go something like, “Well, I don’t believe what Politician X has to say about the tax plan because he has said some absolutely crazy things in the past.” It may be true that Politician X has proven himself to be a nut job on a variety of issues, and this may affect his ethos, but it does not logically disprove what he has to say about the tax plan. He might be wrong on everything but this one issue.

- Argumentum ad populum– concluding an argument is true simply because lots of people think it’s true. We see this on commercials all the time: “9 out of 10 doctors recommend Acme Brand Toothpaste,” or “3 million Brand X Customers Can’t be Wrong! Buy Brand X Today.”

- Appeal to authority- concluding an argument is true because a person holding authority asserts it is true. “Doctor Who is an expert in quantum physics. If he says time travel is possible, then it must be true!”

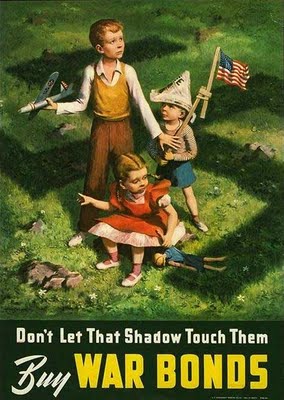

- Appeal to emotion- instead of appealing to reason, the arguer uses emotions such as fear, pity, and flattery to persuade the listener that what he says is true. Wartime propaganda posters are a good example of an appeal to emotion:

- Appeal to motive- a conclusion is dismissed by simply calling into question the motive of the person or group proposing the conclusion. You’ll often see political organizations use this tactic. “The conclusion of Company X’s positive report on the safety of natural gas fracking can’t be true because they funded the research and have an interest in ensuring there is a positive report.” Sure, Company X may have an interest in getting a positive result for natural gas fracking, but just because they have that motive doesn’t mean the conclusion they reached is necessarily false. Suspect, yes, but not false.

- Appeal to tradition- concluding an argument is true because it has long been held to be true.

- Argument from silence- reaching a conclusion based on the silence or lack of contrary evidence. Example: “Aliens must not exist because we haven’t made contact with them.”

- Reductio ad Hitlerum- comparing an opponent or their argument to Hitler or Nazism in an attempt to associate a position with one that is universally reviled. People seem to use this one a lot on the web. Example: “You know who else was a vegetarian? Hitler. Therefore, vegetarianism is bad.”

- Strawman– an argument based on an misrepresentation of an opponent’s position. It’s called a strawman because the person sets up a false point (the strawman) that the original arguer never made and expends all his energy attacking it, instead of the actual premises of the original argument. Example: “Senator Smith wants to cut funding for the new Air Force fighter jet because he says it’s wasteful spending. I disagree with the Senator’s stance. Why does Senator Smith want to leave our country defenseless?” Instead of debating whether the jets are actually government waste, the arguer ignores that point and instead substitutes a misrepresented version of the senator’s position, i.e. the senator wants to leave our country defenseless.

- Appeal to hypocrisy- an argument that a certain position should be disregarded or is wrong, based on the fact that the proposer of the position fails to act in accordance with that position. Example: “Your point that entitlement programs should be eliminated is moot based on the fact that you’ve received Pell Grants and used food stamps while in college.” Sure, it’s hard to take someone seriously when they’re simultaneously using government programs and arguing for their elimination, but just because a guy doesn’t practice what he preaches, doesn’t automatically make what he’s preaching false. Instead, the debate should be focused on the pros and cons of government programs themselves.

Slippery Slope

Slippery slopes occur when a person asserts that a relatively small step will lead to a chain of events that result in a drastic change. Example: “If we legalize same sex marriage, what will stop us from legalizing marriage between humans and robots? Or humans and animals?”

Cherry Picking

Fallacy that occurs when a person only uses data that confirms a particular position, while ignoring a significant portion of related cases that contradict that position. For example, a person might argue that a vegan diet prevents cancer while ignoring cases of cultures that eat only meat and have very low cancer rates.

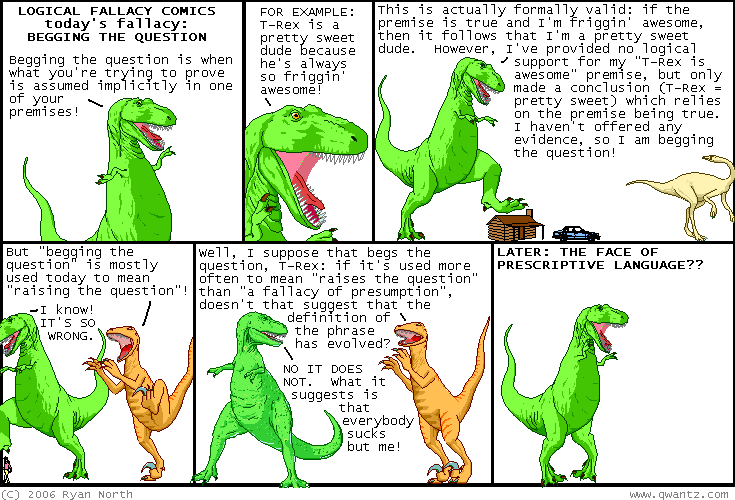

Begging the Question

Fallacy that occurs when the conclusion of an argument is assumed in one of the premises. It’s also often called circular reasoning. If one’s premises entail one’s conclusion, and one’s premises are questionable, one is said to beg the question.

Here’s one of my favorite webcomics, Dinosaur Comics explaining begging the question:

Post hoc ergo propter hoc

Latin for “after this, therefore because of this.” A fallacy that occurs when someone reaches a conclusion of causation because an event followed another event. Example: “It started to rain after my ice cream cone fell on the ground. Therefore, my ice cream falling on the ground caused it to rain.”

False Dilemma

A fallacy that occurs when two conclusions are held to be the only possible options, when in fact there are other options. Example: Senator A: “We either have to cut education spending or else we’ll have a huge deficit this fiscal year.” Senator B: “Hmmm…there are other options. You could raise taxes or even cut spending in other programs and agencies.”

This list is by no means exhaustive. There are dozens more informal fallacies. If you’re interested in finding out more about informal fallacies, check out the following resources:

I’d love to read what informal fallacies are your favorites to point out. Share them with us in the comments.

Using Informal Fallacies to Persuade

Reading through that list of informal fallacies, you likely stopped a few times, and thought, “Wait, but isn’t that a persuasive argument? Shouldn’t we appeal to experts, to tradition? Isn’t a slippery slope possible? Shouldn’t the character of the messenger have something to do with whether their message is believable?”

One must remember that that while sometimes they can be one and the same, there can be a difference between an argument that is logical and one that is simply persuasive.

And sometimes it’s okay to use the latter.

What the what? Only a cad would purposely use informal fallacies in an argument, right? Well, yes and no. It’s important to remember that rhetoric is fundamentally about persuasion, and not only about crafting arguments that are perfectly logical. If we weren’t allowed to use informal fallacies in our rhetoric than two of the three means of persuasion would be off limits–ethos (appeal to the speaker’s character) and pathos (appeal to emotions). Both are informal logical fallacies.

Politicians and advertisers understand that human beings are persuaded more by emotion than by reason. That’s why you see politicians and advertisers use informal fallacies all the time.

It does create an ethical dilemma for a rhetorician. Should one eschew appeals to emotion or character because they’re not strictly logical? While using only logic and sound reasoning may seem like taking the high road, a rhetorician risks being ignored and never getting an important message to the masses. Some of the greatest speeches in history were based on both logic and emotion. Going back to the example of propaganda posters during WWII…the government needed to fund the war effort quickly and effectively; simply appealing to logic wouldn’t have accomplished what was necessary. Instead, appealing to Americans’ sense of duty, patriotism, and worry for their loved ones motivated citizens to action. Used for honorable purposes, appeals to ethos and pathos can move people to do great things. And of course in the wrong hands, they can persuade people to do evil. That’s why it’s important to have an informed and intelligent citizenry that is able to evaluate the claims and appeals made by leaders and pundits, allowing themselves to be caught up in emotion when the cause is sound, and cutting through the illusion when it is not.

Everyone is going to have a different answer as to whether or not using informal fallacies is justified. I think the key is to find a balance. Use appeals to emotion or character, but always have some actual facts and sound reasoning to back up those appeals.

_______________________________________________________

Well, that does it for this series on classical rhetoric. We plan on putting the posts together into an ebook for those who are interested in having all the posts in one place. Although such projects always seem to take us forever to finish, since they’re often placed on a distant burner on the large AoM oven.

I’ll leave you with a list of resources that were helpful to me in researching this series and can help you continue your study of classical rhetoric.

- Silva Rhetoricae

- The Art of Rhetoric by Aristotle

- On Invention by Cicero

- Rhetorica ad Herennium attributed to Cicero, but he probably didn’t write it.

- Institutio Oratoria by Quintilian

- A Handlist of Rhetorical Terms

- The Lost Art of the Great Speech

- Made to Stick: Why Some Ideas Survive and Others Die

- Speak Like Churchill, Stand Like Lincoln

- Thank You for Arguing: What Aristotle, Lincoln, and Homer Simpson Can Teach Us About the Art of Persuasion

Classical Rhetoric 101 Series

An Introduction

A Brief History

The Three Means of Persuasion

The Five Canons of Rhetoric – Invention

The Five Canons of Rhetoric – Arrangement

The Five Canons of Rhetoric – Style

The Five Canons of Rhetoric – Memory

The Five Canons of Rhetoric – Delivery

Logical Fallacies

Bonus! 35 Greatest Speeches in History