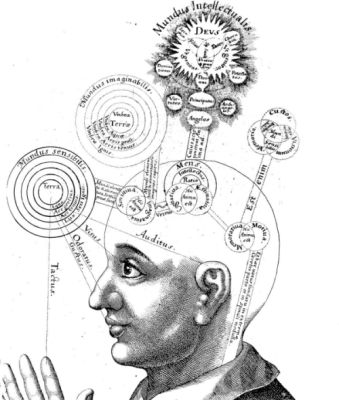

Demosthenes practicing his delivery by the ocean.

Welcome back to our series on Classical Rhetoric. Today we’re continuing our five-part segment on the Five Canons of Rhetoric. So far we’ve covered the canons of invention, arrangement, style, and memory. Today we’ll be covering the last canon: delivery.

What Is Delivery?

Like the canon of style, the canon of delivery is concerned with how something is said.

While the canon of style focuses primarily on what sort of language you use, delivery focuses on the mechanics of how you impart your message. For ancient orators, delivery meant how a speaker used his body language and hand gestures and how he changed his tone of voice during his oration.

Mastering the canon of delivery can help a speaker establish ethos with his audience. Admit it. You’ve probably written off plenty of speakers when you saw that they mumbled through their speech and gestured like the robot on Lost in Space. I know I have. The speaker could have been making valid and groundbreaking points, but the message got lost in the delivery. Delivery can also help an orator use pathos, or emotion, to persuade. A well placed pause or a slammed fist can elicit a desired emotion from your audience in order to make your point.

The ancient Greeks held the canon of delivery in very high regard. They believed that an orator who could eloquently deliver a speech was in fact a virtuous person. The thinking being that the gift to deliver a powerful speech could only reside in a virtuous man.

The life of the famous Greek orator Demosthenes demonstrates the lengths ancient rhetoricians would take in order to master the canon of delivery. To improve his diction, Demosthenes would practice his speeches with pebbles in his mouth and even recite speeches while he ran. To strengthen his voice so he could be heard clearly in the Greek Assembly, he’d stand on the seashore and deliver his speech over the roar of the waves. All this work paid off, as Demosthenes went down in history as one of the greatest orators of ancient Greece.

While the Greeks admired men as virtuous for being able to deliver a speech eloquently, modern audiences have a tendency to be suspicious of a speaker that appears too well-polished. A charismatic speaker who can deliver a rousing speech is often seen as a silver-tongued deceiver with ulterior motives, someone who is masking his true intent with a flashy presentation. This suspicion was born in the aftermath of WWII; people felt ashamed that they had fallen under the spell of dictators who were great orators but had malicious agendas.

But for Americans, our wariness of smooth speakers goes back quite a ways more and can be traced to the cultural turn against the “genteel patriarch archetype” after the Revolutionary War and the election of Andrew Jackson as the country’s first “populist president.” Since that time, Americans have craved “authenticity” and often preferred a speaker with a bit of rough, folksy charm over one more refined and sophisticated. We saw this play out in the 2004 U.S. presidential election between John Kerry and George Bush. Many political commentators agreed the John Kerry had a hard time connecting with voters because he came off as too polished, stiff, and cerebral in debates and speeches. Bush, on the other hand, despite his occasional speaking gaffes, or perhaps because of them, was often seen as more down-to-earth–the kind of guy you’d go have a beer with–because his delivery was more rough and unpolished. He seemed authentic and approachable, and thus trustworthy. Some cultural commentators saw the election of Obama in 2008 as a victory over this suspicion for “elitism” and charismatic orators.

The Importance of Tailoring Your Delivery to Your Audience

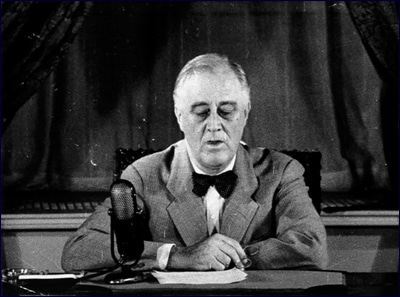

FDR knew how to match his style of delivery to the situation.

How you approach your delivery will need to be determined during the invention stage of your speech. Find out to the best of your ability the overall demographics and cultural background of your audience. What does your audience fear? What are their desires? What are their needs? This information will help you decide if you should use a more sophisticated and polished delivery or if you should go with a more informal approach.

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt was a master of understanding the importance of tailoring your delivery according to time, place, and audience.

When FDR took office during the Great Depression, he instituted regular “Fireside Chats,” where he would address the country on the radio to discuss what the government was doing and why. If you listen to him, say, explain the need to close banks for a banking holiday, you can hear how his delivery sounds much like a kindly grandfather patiently explaining a complicated issue in a very simple and easy to understand manner. His delivery conveys warmth, comfort, and confidence. It is easy to understand how, in a time where there was “nothing to fear but fear itself,” many Americans, in a practice foreign to most of us today, had a picture of FDR hanging in their home as if he were part of the family.

Now, if you listen to FDR’s speech after the bombing at Pearl Harbor, you can hear a much different, but still very effective kind of delivery. The nation was reeling with shock, worry, and anger, and FDR, now speaking with great force, manages to convey righteous indignation and supreme confidence.

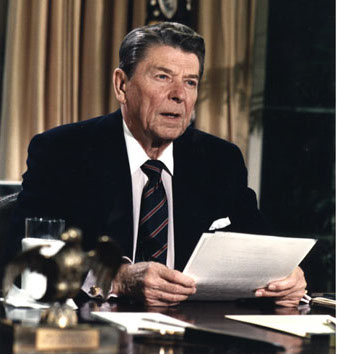

Like FDR, Reagan knew how to effectively vary his delivery. He could often be humorous and folksy but knew how to convey sincerity and solemnity when the situation called for it, such as after the Challenger exploded.

Developing the Canon of Delivery in Oratory

Because the art of delivery in writing could be its own post, we have chosen to concentrate on how it applies to spoken rhetoric. Here are a few key tips for increasing the effectiveness of your oratorical delivery.

Master the pause. Most people are so nervous when they get up to speak that they rush through the whole thing like the Micro Machines guy. But they’re losing out on employing one of the most powerful oratorical techniques–the pause. A pause can add a bit of dramatic flair to a statement or it can help the audience really drink up an idea. The key with a pause is timing. Use it only in spots where it will be effective–places where you really want to highlight what comes after the pause. “Hello (pause) my (pause) name is (pause),” would not be such a time. Practice inserting pauses in your speech to find what works.

Watch your body language. When you’re speaking, your voice isn’t the only thing talking. Your body is also communicating. Your posture, head tilt, and the way you walk on stage all convey a message. Some occasions may require that you carry yourself in a more formal and stiff manner, while other occasions will require a more laid-back approach.

Vary your tone. Nothing will put your audience to sleep faster than a visit from android man from the year 2050. Short-circuit the flat, monotonous robot voice and keep things interesting by adding vocal inflections as you speak. Use inflections to reveal that you’re asking a question, being sarcastic, or conveying excitement. You might even exaggerate your inflections when delivering a public speech as many people have a tendency to get timid in front of an audience.

Let gestures flow naturally. If used effectively, hand gestures can give added emphasis to your words. If used incorrectly, you’ll end up looking like an octopus having a seizure. Don’t over think hand gestures; just let them flow naturally. You might want to have someone watch you practice the speech to make sure your gesticulations aren’t distracting. If they are, adjust accordingly, but don’t obsess about it; they’re part of what makes you unique as a speaker.

Nothing stops a Bull Moose’s hand gesture.

Match your speed with your emotion. How fast or slow you speak can affect the emotion you’re trying to convey. In A Natural System of Elocution and Oratory, the author gives six different speech speeds and the corresponding emotions they’re meant to elicit.

- Rapid: haste, alarm, confusion, anger, vexation, fear, revenge, and extreme terror.

- Quick or brisk: joy, hope, playfulness, and humor.

- Moderate: good for narration, descriptions, and teaching.

- Slow: gloom, sorrow, melancholy, grief, pity, admiration, reverence, dignity, authority, awe, power, and majesty.

- Very slow: used to express the strongest and deepest emotions.

Vary the force of your voice. Force is the strength and weakness of voice. Varying the force of your voice can help express different emotions. Anger, ferocity, and seriousness can be conveyed with a strong, loud voice. This doesn’t mean you need to shout. You just need to put a little more oomph in your voice. A softer voice can convey reverence, meekness, and humility. Varying the force of your voice can also help draw listeners into your speech. For example, by speaking softly, your audience has to work a bit more to hear you. It’s almost like you’re telling a secret to your audience which is a great way to emphasis a point you’re making and to connect with your listeners. Like all tactics, this must be used sparingly…don’t make the audience strain to hear your whole speech.

Enunciate. It’s easy to trip over your tongue and slur words together when you’re speaking in public. But really focus on enunciating your words as this will make you easier to understand. I have a tendency to mumble and slur words together. A trick that has helped me overcome this is practicing speaking while holding a pencil underneath my tongue. It forces your tongue to work harder as it restricts tongue movement. When you remove the pencil from underneath your tongue, you’ll be amazed at how much easier it is to enunciate without the obstruction. I’ll often do this exercise right before I do a podcast or give a presentation. Tongue twisters help with enunciation, too.

Look your audience in the eye. When you look people in the eye, you make a connection. But how can you look an entire audience in the eye? Well, if there are hundreds of people in your audience, you can’t. But you can at least make eye contact with a couple of them. As you go through your speech, work your way across the room making eye contact with several different people in the audience. You’ll get a strong connection with those people you look in the eye, but you’ll also give everyone else a chance to look you in the face which can help build a connection. Maintain contact for a few seconds. If it’s too short, you’ll seem nervous and shifty. If you look too long, you’ll start creeping people out.

Classical Rhetoric 101 Series

An Introduction

A Brief History

The Three Means of Persuasion

The Five Canons of Rhetoric – Invention

The Five Canons of Rhetoric – Arrangement

The Five Canons of Rhetoric – Style

The Five Canons of Rhetoric – Memory

The Five Canons of Rhetoric – Delivery

Logical Fallacies

Bonus! 35 Greatest Speeches in History